История поэмы “Медный всадник” Пушкина

С самого момента основания города Санкт-Петербурга его реальная история интерпретировалась и описывалась различными авторами. Город описан в произведениях литературы и искусства с точки зрения реальной истории. Очень тонко история города описана у Пушкина, в ней он описал и историю создания города, и его великих создателей. История поэмы «Медный всадник» Пушкина сама по себе отличается оригинальностью. Но всему великому предстоит пройти сложный путь – это мы можем наблюдать как в самой поэме, так и на примере ее истории.

Реальное наводнение

Историческая основа произведения – наводнение в Петербурге, которое случилось осенью 1824 года. В это время Пушкина в городе не было. В произведении наводнение описано со слов очевидцев. Реальное историческое событие стало не только трагедией в обычной жизни. Оно послужило основой для создания художественного образа и получило вековую память в лице читателей произведения гениального автора. Наводнение унесло жизни множества людей, стало настоящей трагедией для города. После него были приняты меры, безопасность города была поднята на более высокий уровень. Тем не менее, трагедия успела случиться, унеся с собой жизни многих жителей город. Перед стихией оказался бессилен не только простой человек, но и цари, сам город, вся система.

Как была написана поэма

История создания «Медного всадника» не проста. Не смотря на то что поэма была написана в короткий срок – меньше чем за месяц, в октябре 1833 года, Пушкин вложил в нее много сил. Каждый стих Пушкин переписывал по несколько раз. В итоге ему удалось совместить в короткой поэме множество образов, символов, значений. Произведение было написано в Болдино, после путешествия Пушкина на Урал по местам, которые связаны с пугачевским бунтом. Возможно, образ ожившего памятника Пушкину пришел после того, как Александр I запланировал вывезти памятник из города. Но одному из майоров приснился сон, как Медный всадник скачет по городу, подъезжает к императору и говорит о том, что нынешний правитель довел жизнь в стране до трагедий, но пока памятник на месте- он следит за городом и ничего ему не будет страшно. Это остановило Александра, а поверье о хранителе города Медном всаднике живет до сих пор.

Цензура и публикация

Когда Пушкин вернулся из Болдино, он передал свою поэму на цензуру. Вернули ему произведением с большим количеством правок. Александр Сергеевич верил, что рукопись читал сам Николай, но позже выяснилось, что вычиткой занимались служащие политической полиции. Запрещена поэма не была, но Пушкин воспринял это как запрет. Автор пытался переписать забракованные фразы и места. Но это было выше его сил и он бросил эту затею. При жизни Пушкина поэма не была опубликована, вышло лишь вступление в журнале «Библиотека для чтения».

Данная статья поможет грамотно написать сочинение на тему «История поэмы «Медный всадник» Пушкина», указать связь с реальными событиями, историю написания и публикации произведения.

Посмотрите, что еще у нас есть:

Тест по произведению

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Shch Dimont

11/11

-

Павел Захаркин

8/11

-

Юлия Хачак

11/11

-

Валерия Абрамова

11/11

-

Александр Дудышев

11/11

-

Татьяна Глазкова

11/11

-

Арина Сотникова

11/11

-

Михаэль Смайликов

11/11

-

Александр Тихообразов

8/11

-

Мария Ванилькина

11/11

На чтение 7 мин Просмотров 1.1к. Опубликовано 23.03.2022

Поэма «Медный всадник» представляет собой одно из наиболее емких и сложных произведений Александра Сергеевича Пушкина. Оно было написано осенью 1833 года. При этом поэт работал над своим творением в знаменитом Болдине. Это время года и место дарили гению удивительное вдохновение. Чтобы лучше понимать суть произведения, важно знать историю создания поэмы «Медный всадник».

История создания поэмы «Медный всадник» А. С. Пушкина

Это произведение отличается непростой историей создания. Несмотря на то, что поэма была создана в короткие сроки, Пушкин вложил в нее много сил. Многие люди интересуются, когда написано произведение. Оно датируется 1833 годом.

Каждое стихотворение Пушкин многократно переписывал. В результате ему удалось совместить в небольшой поэме много образов и символов. Произведение создано в Болдино – после поездки Александра Сергеевича на Урал. Объектом его интереса были места, связанные с бунтом Пугачева.

Вероятно, идея памятника, который оживает, появилась у поэта в тот момент, когда Александр I решил вывезти его из города. Но один майор увидел сон, что Медный всадник передвигается по городу и приближается к императору. Он обвиняет правителя в том, что тот довел жизнь до трагических событий, но пока монумент на месте, бояться не стоит. Это остановило царя, а легенда о Медном всаднике жива по сей день.

Наводнение в Питере

В основу произведение легло петербургское наводнение, которое произошло в 1824 году. Тогда Пушкин отсутствовал в городе. Наводнение он описывает со слов людей, которые выступили очевидцами. Это событие не стало просто трагедией в жизни обыкновенных людей. Оно легло в основу художественного произведения и было увековечено в пушкинской поэме.

Наводнение в Петербурге забрало жизни многих людей и превратилось в настоящую трагедию для города. После этого были приняты меры, и город стал намного безопаснее. Тем не менее, катастрофа успела произойти и забрала жизни многих жителей. Перед природным бедствием оказались бессильны не только обычные люди, но и правители, город, система.

Сюжет произведения

Произведение описывает судьбу обычного молодого парня Евгения, который только начинает взрослую жизнь. Ничем не примечательный юноша мечтает жениться на любимой девушке Параше и мирно прожить на окраине Петербурга.

Однако внезапно его планы рушит опасная стихия. После страшного бедствия, которое ненадолго разлучило влюбленных, юноша мчится к дому Параши и видит, что возлюбленной больше нет в живых.

Страшное горе приводит к тому, что молодой человек попросту теряет свой разум. Он бесцельно бродит по городским улицам и пытается отыскать виновника ужасной трагедии.

Проходя около статуи Петра I, который основал Петербург, Евгений упрекает ее «Ужо тебе!» и грозит кулаками. Вдруг каменный император сходит с постамента и гонится за юношей. Обессилевший молодой человек пугается видения и гибнет.

Трагедию маленького человека никто не замечает. Нева продолжает величественно течь, и Петербург продолжает вести привычный образ жизни.

Произведение включает различные смысловые акценты. Поэма обладает линейным построением. При этом ее структуру нарушают исторические детали. По мере развития сюжета автор объединяет два временных потока – прошлое с настоящим.

В объемном прологе Пушкин описывает хорошие деяния Петра, одним из которых стало основание Петербурга. В основной части описывается страшное стихийное бедствие – наводнение. Ложной кульминацией является осознание гибели Параши, а ложной развязкой – сумасшествие Евгения.

При этом в действительности в качестве кульминации стоит рассматривать обращение молодого человека к памятнику Медного всадника. При этом развязкой считается погоня памятника за дерзким юношей. Поэма не имеет графически обозначенного эпилога. Последние четверостишия описывают гибель главного героя, что и является эпилогом.

Главные герои повести

Автор описывает свою поэму как «горестный рассказ» и говорит, что все события в ней правдивы. К основным героям относятся:

- Евгений – чиновник, который имеет знатное происхождение. При этом он очень беден. Юноша готов много трудиться, чтобы заработать на жизнь. Он арендует комнату в одном из петербургских районов – в Коломне. Там живут ремесленники и небольшие чиновники. Герой мечтает встретить возлюбленную, живущую на другом берегу Невы. Непогода приводит к тому, что река разливается. Это препятствует встрече влюбленных. Все помыслы героя направлены в будущее. Он надеется на счастливую семейную жизнь.

- Медный всадник – олицетворяет Петра Великого. Пушкин использует его как двойной образ. С одной стороны, правитель защищает слабых людей и является отцом просвещения, с другой – его можно рассматривать как грубого самодура, который приносит людям много бед.

В произведении имеются и второстепенные персонажи. К ним относят Парашу – любимую Евгения. Она живет в небольшом домике, расположенном на другом берегу. Есть в поэме и фигура перевозчика, который соглашается в непогоду перевезти юношу на берег, где живет его возлюбленная.

Особая роль в поэме отводится образу Петербурга. Белинский утверждает, что город можно считать главным героем произведения. Его описанию автор уделяет особенное внимание. Наиболее детально оно рассматривается во вступлении, в котором поэт описывает местность до и после основания города. Изначально это болотистые места, которые практически не заселены людьми. Спустя 100 лет Петербург превратился в большой город с красивыми величественными зданиями. С разных уголков земли в него заходят корабли.

Автор не таит любви к городу. Он описывает белые ночи и морозные зимы. Особенное внимание Пушкин уделяет наводнению 1824 года, после которого город долгое время не может прийти в себя.

Цензура и публикация

После возвращения Пушкина из Болдино он отдал свою поэму на цензуру. Однако она была возвращена со множеством правок. Автор был уверен, что чтением рукописи занимался сам Николай, однако впоследствии выяснилось, что вычиткой стихотворения занимались работники политической полиции.

Труд Пушкина не запретили, однако поэт воспринял правки цензоров именно так. Он пытался изменить места и фразы, которые были забракованы. Однако сделать это поэт не смог и отказался от затеи. При жизни «Медный всадник» так и не был издан. В журнале «Библиотека для чтения» напечатали только вступление поэмы.

Критика

Поэму анализировали многие критики. Белинский отмечал, что в произведении описывается горькая судьба человека, который страдает от проживания в новейшей местности Петербурга. Город создан на болотистой местности, что пошло вразрез с особенностями природы. Так же и человек, имеющий подавленное сердце, в произведении Пушкина признает, что общее побеждает частное. Критика восхищает описание автором картины наводнения. Белинский говорит о величии поэзии гения.

Критик Дружинин тоже описывает талант Пушкина с уважением. Он уверен, что поэма о всаднике будет актуальна не только для современников. Ее поймут и признают все. Дружинин отмечает, что она будет воспринята людьми не только в оригинале, но и в переводе. Критик видел в поэме слияние истории конкретного человека со всем народом. Он утверждал, что суть творения Пушкина близка каждому.

Мережковский подчеркивал, что в произведении описывается судьба двух основных героев. Пушкин описывает обычного человека, который довольствует малым. Вторым образом считается мощный исполин, которые предстает в поэме в виде памятника Петру Великому. Он не интересуется проблемами обычных людей, которые должны погибать за идеи правителей.

Что же случится, если простой человек восстанет против царя? Вызов персонажа поэмы нарушает покой Медного всадника. Он приходит в ярость и пытается догнать безумца, воспротивившегося системе. Но суть произведения заключается в то, что громкие шаги исполина не способны заглушить шепот обычного человека.

Критики восприняли произведение по-разному, потому существует много трактовок поэмы. Тем не менее, все они сошлись, что автору удалось точно передать общественную ситуацию, которая будет доступна потомкам и сохранит свою актуальность еще много лет. Поэма отличается масштабностью и глубиной содержания. Она не содержит эпилога, потому противоречия между государством и конкретным человеком остаются открытыми.

Заключение

«Медный всадник» – гениальное произведение Пушкина, которое поднимает ключевые общественные проблемы. Чтобы лучше понимать значение творения великого поэта, важно изучить историю его создания и проанализировать роль каждого из персонажей произведения.

Медный всадник (Пушкин) — история создания

Романтическая поэма «Медный всадник» была написана А.С. Пушкиным в 1833 году. Поэт занимался её сочинением в течение октября-месяца, находясь в это время в Болдине. Несмотря на небольшой объём, поэма стоила Пушкину значительных усилий. Он переделывал каждый стих по множеству раз. «Медный всадник» считается одной из самых коротких поэм этого гения, однако по смысловому наполнению она весьма ёмка и содержательна.

Произведение заполонено различными смыслами, образами, аллегориями. В нём затронута не только тема города Петра, европеизация России, грандиозное наводнение, но и конфликт между венценосным строителем Петром I и бедным молодым человеком Евгением, с его скромными желаниями и мечтами.

А может быть, поэта «зацепило» произведение «Дон Жуан», и он решил в своей поэме тоже развить тему ожившего памятника. Или Пушкин услышал легенду о том, как Александр I собирался вывезти «Медного Всадника» из города, но, узнав о вещем сновидении придворного майора, отказался от этой затеи (во сне памятник Петру I назвался хранителем Петербурга и сказал, что пока он стоит на своём месте, городу ничего не угрожает). Есть также вероятность того, что идею поэмы растревоженный поэт привёз из путешествия по уральским местам, связанным с пугачёвским восстанием.

Пушкин назвал свою поэму «Медный всадник», хотя знал, что памятник не полностью состоит из этого металла, некоторые его части изготовлены из железа и бронзы. Вероятно, этим названием автор хотел охарактеризовать царя-строителя города как медноголового, упрямого человека. Петр I смог укрепить государство, дать ему выход к морю, построить красивейший город, но при этом было разрушено множество судеб простых людей. В масштабах истории это не имеет большого значения, но для конкретного человека превращается в трагедию. Именно такую трагедию «маленького человека» показывает Пушкин в своей поэме.

Однако история создания «Медного всадника» не ограничивается только замыслом и воплощением – произведению еще предстояло дойти до читателя. Как только поэма была написана, она тотчас была передана цензорам на проверку. Вернулась рукопись с большим количеством правок. Пушкин считал, что поэму проверял сам государь Николай I и был сильно расстроен неудачей. Хотя строгость цензора, возможно, была связана со скорым открытием другого царственного памятного сооружения – «Александрийского столпа».

Поэт попытался произвести требуемые исправления, но из этого ничего хорошего не получилось – и он отложил рукопись до лучших времён. При жизни Пушкина в свет вышел только небольшой отрывок из поэмы. Полностью произведение было напечатано в 1837 году, с правками В.А. Жуковского, а в оригинале текст увидел свет лишь в 1904 году.

Эпилог в произведении отсутствует – тема противоречий между народом и государственными структурами не закрыта. Поэма «Медный всадник» актуальна до сих пор. Принимая решения, руководитель государства должен помнить о своей ответственности за судьбу каждого человека.

- Сочинения

- По литературе

- Пушкин

- История создания поэмы Медный всадник

История создания поэмы Медный всадник Пушкина (прототипы героев, история публикации)

«Медного всадника» поэт написал менее чем за месяц, осенью 1833 года в Болдине. Работал над поэмой меньше месяца. Это произведение стало одним из лучших на вершине его творчества.

События поэмы имеют исторические корни. Пушкин стал свидетелем наводнения на Неве в августе 1833 года и ему вспомнились трагические события, которые произошли в Петербурге в 1824 году, когда сильное наводнение нанесло большой ущерб простому народу, многие люди погибли в стихии. Поэт не был свидетелем тому, ибо был в Михайловской ссылке, но очень переживал за пострадавших людей, на которых не обращали внимания богатые сословия. Рассказы очевидцев трагедии поразили поэта.

И вот спустя 9 лет он задумал вылить свое переживание по этому поводу на бумагу. Черновиков поэмы выявлено было очень мало, он писал почти всю ее начисто, временами меняя и переписывая строки. Последние правки к поэме поэт сделал уже в Петербурге и потом отдал ее на цензуру.

Цензура строго отнеслась к произведению, определив в некоторых местах политическую направленность. Пушкину сделали много замечаний, и он был расстроен этим. Только в 1834 году он отдал к публикации вступление к поэме, продолжая делать в ней правки.

В 1836 году поэма с правками опять была подана на цензуру, но автор не убрал некоторых мест, что особо не нравились царю, поэтому поэма опять не была напечатана. И только после смерти поэта она увидела свет в журнале «Современник», но уже с правками, которые внес Жуковский.

Прототипами героев поэмы являются Петр I и простой народ в образе Евгения, простого мещанина – отношение государства и личности. Еще один образ постает очень явно. Это образ стихии, что есть общим их врагом.

В начале поэмы Петр I изображен положительно, как великий реформатор и мудрый правитель, просветитель. Но далее в образе медного всадника, что олицетворяет образ Петра, мы видим грубого, деспотичного правителя. Это образ всего государственного строя.

Мелкий чиновник Евгений есть представителем маленьких людей в большом городе. Эти люди бесправны как перед державой, так и перед стихией.

Читая поэму, мы видим много картин из жизни Петербурга, описание города, как величественного, так и печального. В этом городе тяжело жить обыкновенному человеку. Власть имущие не щадят в этом городе никого.

В «Медном всаднике» автор выразил свое видение взаимоотношений Петербурга к маленькому человеку, который не принадлежит к высшему свету, а поэтому не защищен. Толпа и государство к таким людям остаються равнодушными.

Вариант 2

Произведение «Медный всадник» Пушкину удалось написать меньше, чем за месяц. Именно данное произведение стало знаменитым, а также популярным. История создания этого произведения появилась еще очень давно. Однажды Пушкину удалось побывать на Неве. В это время Нева поднялась и потопила огромное количество городов и деревень, которые находились рядом. И от этого погибло очень много людей. Все это запомнилось автору и он решил изложить весь трагизм в своем произведении.

Конечно же, правительство могло бы помочь этим людям и вовремя их эвакуировать и тогда бы ничего не случилось бы, вот только им не хотелось всем этим заниматься, да к тому же у них имеются другие дела, которые не требуют отлагательств и их нужно решить очень быстро. С трагедии прошло около девяти лет и только тогда он, и решился обо всем рассказать. И во время написания он истратил очень мало черновиков, потому что ему ничего не пришлось выдумывать и он написал всю правду, которая может быть мало кому известна. Когда он заканчивал свое произведение, то был в Санкт-Петербурге и именно там и отдал его на проверку.

Пушкину было вынесено очень много замечаний, которые нужно было сейчас же изменить. Кроме этого им не совсем нравилось то, как он описывает правительство. Автор очень сильно расстроился, поэтому поводу, вот только ничего переписывать и изменять не собирался. А вот читать его начали только после того как Пушкин умер. И, конечно же, тут уже появились правки, которые делали другие писатели.

Главными героями здесь стал Петр первый, а также мещанин. Кроме этого здесь сочетается отношение, которое складывается между правительством и обычными людьми.

Сначала Петр первый правильно и точно выполняет свои обязанности и всем людям он очень нравится. Но постепенно все меняется и уже власть отрицательно на него влияет. При чтении города можно понять, что сначала он веселый, но спустя некоторое время он становится жалким и печальным. Постепенно жителям города становится очень трудно и тяжело жить в таких условиях, вот только ничего сделать с этим они не могут. Да и идти против него нельзя, ведь от этого жизнь их станет еще хуже, чем сейчас.

Также читают:

Картинка к сочинению История создания поэмы Медный всадник

Популярные сегодня темы

- Критика о романе Отцы и дети Тургенева (отзывы современников)

С момента публикации романа в журнале «Русский вестник». Являвшимся консервативным изданием, произведение писателя подвергается литературоведческим обществом тщательному анализу по главам

- Сочинение по повести Портрет Гоголя

Знаменитый литератор Н.В. Гоголь мог видеть в жизни, не просто настоящее великолепие, но и тяжелую реальность. Северная столица оказывается для него угрюмым и бледным городом

- Сочинение Кем быть?

Перед каждым школьником рано или поздно встает дилемма: кем быть?

- Сочинение Игры моего детства

Игры были важной частью моей жизни в детстве. Свободного времени было много и нужно было как-то развлекать себя. Но с возрастом я поняла, что эти развлечения повлияли на становления меня и развили во мне определенные качества.

- Анализ рассказа Стальное горло Булгакова

Один из своих автобиографических рассказов Стальное горло великий писатель Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков включил в цикл“Записки юного врача, печатавшийся в таких журналах

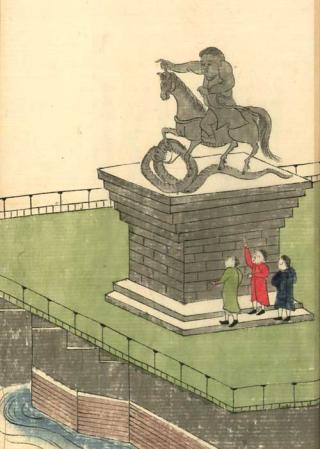

(Памятник императору Петру I (Медный всадник): площадь Декабристов, Адмиралтейский район, Санкт-Петербург. Автор снимка: Lars (Lon) Olsson)

Когда Пушкин жил в Болдино, он ощущал творческий подъем. В этот период он создал много произведений, благосклонно встреченных публикой и критикой. В числе этих произведений и был «Медный всадник».

К написанию поэмы его подтолкнули размышления об истории государства, его правителях и самодержавии. В тот период общество делилось на две части – одна поддерживала политику Петра I, обожала его, а другая находила в императоре сходство с сатаной.

Поэт учитывал разные мнения о самодержце Петре. Поэма стала результатом его мыслей.

О чем поэма , жанр, идея и главный смысл

Автор рассказывает здесь о бедном жителе Петербурга Евгении. Этот персонаж описан поэтом неумным, ничем не выделяющимся от других таких же представителей низкого сословия. Он любил дочку вдовы, которая жила на взморье. Но произошедшее наводнение привело к гибели вдовы с дочерью. И даже дом этих женщин снесло водой. Евгений сошел с ума от горя. Безумец гулял по городу по ночам. И однажды во время прогулки он увидел памятник Петру I. Безумный бедняк прошептал злобные пожелания в отношении человека,которого он считал виновным в своих бедах. Когда бедный безумец отошел от своих мыслей, он вдруг решил, что памятник обижен на него и хочет его наказать. Больное воображение подкидывало одно видение за другим. И в конце концов Евгений умер.

Основной идеей поэмы является мысль о том, что человек, который попал в тяжелую ситуацию, вызванную стихией, может лишиться ума. Но эта идея не единственная . Поэт имел и вторую точку зрения относительно основной идеи произведения.

Автор подводит в мысли, что государство не может стать великим, оно ради этого попирает простого человека.

История создания

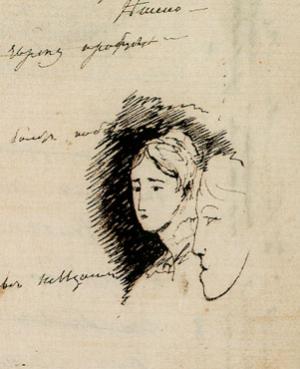

(Портрет Н. Н. Гончаровой (слева) чернила «Медный всадник» (V, 436—437) 6 октября 1833, Болдино)

Считается, что идея об ожившем медном всаднике могла возникнуть у Пушкина,благодаря произведению «Дон Жуан».

Но есть и другая версия. Поэт хорошо знал легенду о якобы помешавшем Александру I удалить из Петербурга памятник Петру I. По этой легенде одному придворному майору приснился вещий сон: памятник ожил и скакал по улицам созданного Петром города. И якобы царь предупредил Александра, что если памятник не будет удален, городу не грозят никакие катаклизмы.

Пушкин удовлетворительного ответа не дал по поводу одной из версий.

Этапы работы

Написал произведение поэт очень быстро, не более чем за месяц. Дата его создания: октябрь 1833 года. Но идея создать поэму, пришла в голову поэта раньше. Ученые-пушкинисты полагают, что у поэта были уже некоторые черновые наброски, сделанные во время пребывания в Петербурге. А в основу легли, скорей всего, события 1824 года, когда город подвергся наводнению.

Но поэму после окончания работы над ней подвергли жесткой критике, даже запретили печатать. Тогдашний император Николай сам лично прочитал ее и сделал замечания автору. Пушкин учел эти замечания и немного переделал текст. После изменений произведение было допущено к печати самим Николаем.

Публикация поэмы

Отрывки вышли в печать уже в 1834 году, но все произведение было напечатано некоторое время спустя, а именно в 1837 году, после смерти поэта.

В статье, сопровождающей публикацию было написано: «Медный всадник» занял в нашей литературе подобающее место и ни один, даже самый строгий судья, не укорит по этому поводу поэта в желании умалить заслуги Великого Преобразователя и оскорбить его священную память». .

Сам автор не увидел свое детище. Да и то, тот вариант, который вышел в печать был переделан Жуковским. Рецензент удалил из текста картину бунта Евгения против Медного императора.

(Из книги «Канкай ибун» («Удивительные сведения об окружающих морях») — памятник Петру I в Санкт-Петербурге. Нарисован японским художником со слов допрошенных моряков, прибитых кораблекрушением к берегам России и через много лет возвращённых в Японию. ~18-19 век)

Публикой и литературными критиками это творение было воспринято мало сказать, что благосклонно. Большинство критиков оценили его как гениальное и считали вершиной творческого гения поэта. Сам же поэт был недоволен вариантом, представленным к печати.

Оригинал без поправок напечатали лишь в 1919 году, после революции. Примерно тогда же напечатана была и история написания поэмы.

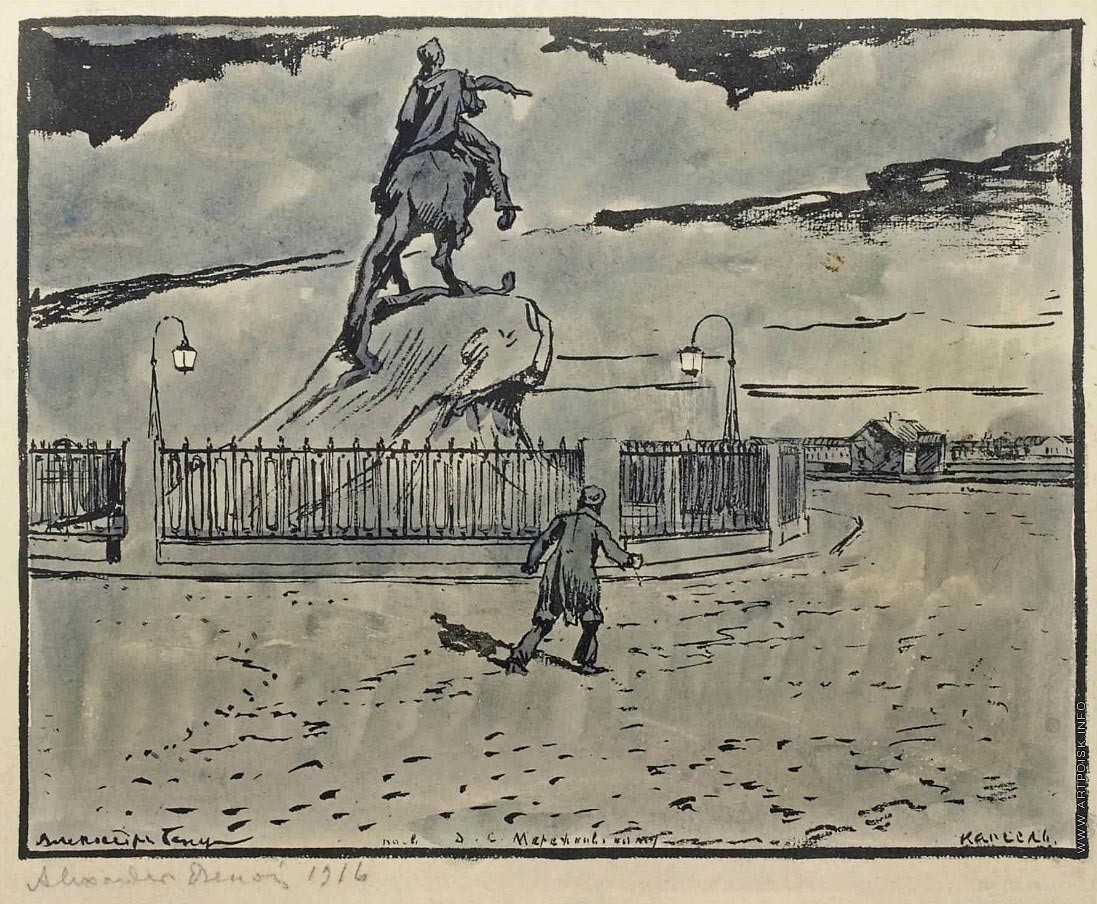

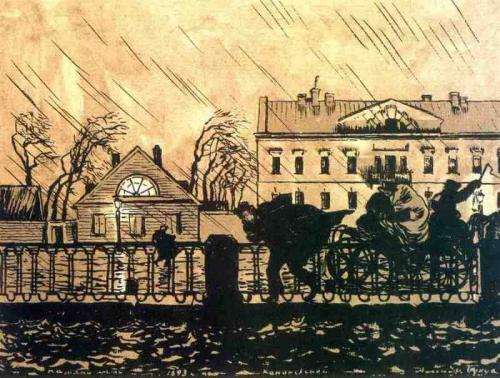

Alexandre Benois’s illustration to the poem (1904). |

|

| Author | Alexander Pushkin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Медный Всадник [Mednyi Vsadnik] |

| Translator | C. E. Turner |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Narrative poem |

| Publisher | Sovremennik |

|

Publication date |

1837 |

|

Published in English |

1882 |

The Bronze Horseman: A Petersburg Tale (Russian: Медный всадник: Петербургская повесть Mednyy vsadnik: Peterburgskaya povest) is a narrative poem written by Alexander Pushkin in 1833 about the equestrian statue of Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg and the great flood of 1824. While the poem was written in 1833, it was not published, in its entirety, until after his death as his work was under censorship due to the political nature of his other writings. Widely considered to be Pushkin’s most successful narrative poem, The Bronze Horseman has had a lasting impact on Russian literature. The Pushkin critic A. D. P. Briggs praises the poem «as the best in the Russian language, and even the best poem written anywhere in the nineteenth century».[1] It is considered one of the most influential works in Russian literature, and is one of the reasons Pushkin is often called the “founder of modern Russian literature.”

The statue became known as The Bronze Horseman due to the great influence of the poem.[2]

Plot summary[edit]

The poem is divided into three sections: a shorter introduction (90 lines) and two longer parts (164 and 222 lines). The introduction opens with a mythologized history of the establishment of the city of Saint Petersburg in 1703. In the first two stanzas, Peter the Great stands at the edge of the River Neva and conceives the idea for a city which will threaten the Swedes and open a «window to Europe». The poem describes the area as almost uninhabited: Peter can only see one boat and a handful of dark houses inhabited by Finnish peasants. Saint Petersburg was in fact constructed on territory newly gained from the Swedes in the Great Northern War, and Peter himself chose the site for the founding of a major city because it provided Russia with a corner of access to the Baltic Sea, and thus to the Atlantic and Europe.

The rest of the introduction is in the first person and reads as an ode to the city of Petersburg. The poet-narrator describes how he loves Petersburg, including the city’s «stern, muscular appearance» (l. 44), its landmarks such as the Admiralty (ll. 50–58), and its harsh winters and long summer evenings (ll. 59 – ll. 84). He encourages the city to retain its beauty and strength and stand firm against the waves of the Neva (ll. 85–91).

Part I opens with an image of the Neva growing rough in a storm: the river is «tossing and turning like a sick man in his troubled bed» (ll. 5–6). Against this backdrop, a young poor man in the city, Evgenii, is contemplating his love for a young woman, Parasha, and planning to spend the rest of his life with her (ll. 49–62). Evgenii falls asleep, and the narrative then turns back to the Neva, with a description of how the river floods and destroys much of the city (ll. 72–104). The frightened and desperate Evgenii is left sitting alone on top of two marble lions on Peter’s Square, surrounded by water and with the Bronze Horseman statue looking down on him (ll. 125–164).

In Part II, Evgenii finds a ferryman and commands him to row to where Parasha’s home used to be (ll. 26 – ll. 56). However, he discovers that her home has been destroyed (ll. 57–60), and falls into a crazed delirium and breaks into laughter (ll. 61–65). For a year, he roams the street as a madman (ll. 89–130), but the following autumn, he is reminded of the night of the storm (ll. 132–133) and the source of his troubles. In a fit of rage, he curses the statue of Peter (ll. 177–179), which brings the statue to life, and Peter begins pursuing Evgenii (ll. 180–196). The narrator does not describe Evgenii’s death directly, but the poem closes with the discovery of his corpse in a ruined hut floating on the water (ll. 219–222).

Genre[edit]

Formally, the poem is an unusual mix of genres: the sections dealing with Tsar Peter are written in a solemn, odic, 18th-century style, while the Evgenii sections are prosaic, playful and, in the latter stages, filled with pathos.[3] This mix of genres is anticipated by the title: «The Bronze Horseman» suggested a grandiose ode, but the subtitle «A Petersburg Tale» leads one to expect an unheroic protagonist[4] Metrically, the entire poem is written in using the four-foot iamb, one of Pushkin’s preferred meters, a versatile form which is able to adapt to the changing mood of the poem. The poem has a varied rhyme scheme and stanzas of varying length.[5]

The critic Michael Watchel has suggested that Pushkin intended to produce a national epic in this poem, arguing that the Peter sections have many of the typical features of epic poetry.[6] He points to Pushkin’s extensive use of Old Testament language and allusions when describing both the founding of St Petersburg and the flood and argues that they draw heavily on the Book of Genesis. Further evidence for the categorization of Pushkin’s poem as an epic can be seen in its rhyme scheme and stanza structure which allow the work to convey its meaning in a very concise yet artistic manner.[7] Another parallel to the classical epic tradition can be drawn in the final scenes of Evgenii’s burial described as “for God’s sake.” In Russian, this phrase is not one of “chafing impatience, but of the kind of appeal to Christian sentiment which a beggar might make” according to Newman.[8] Therefore, it is a lack of empathy and charity in Petersburg that ultimately causes Evgenii’s death. The requirement that civilization must have a moral order is a theme also found in the writings of Virgil.[8] However, he adds that the Evgenii plot runs counter to the epic mode, and praises Pushkin for his «remarkable ability to synthesize diverse materials, styles and genres».[9] What is particularly unusual is that Pushkin focuses on a protagonist that is humble as well as one that is ostensibly great. There are more questions than answers in this new type of epic, where “an agnostic irony can easily find a place” while “the unbiased reader would be forced to recognize as concerned with the profoundest issues which confront humanity”.[10] He concludes that if the poem is to be labeled a national epic, it is a «highly idiosyncratic» one.[9]

Historical and cultural context[edit]

Several critics have suggested that the immediate inspiration for «The Bronze Horseman» was the work of the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz.[11][12] Before beginning work on «The Bronze Horseman», Pushkin had read Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve (1823–32), which contains a poem entitled «To My Muscovite Friends», a thinly-veiled attack on Pushkin and Vasily Zhukovsky for their failure to join the radical Decembrist revolt of 1825. Forefather’s Eve contains poems where Peter I is described as a despot who created the city because of autocratic whim, and a poem mocks the Falconet statue as looking as though he is about to jump off a precipice. Pushkin’s poem can be read in part as a retort to Mickiewicz, although most critics agree that its concerns are much broader than answering a political enemy.[13]

There are distinct similarities between Pushkin’s protagonist in The Bronze Horseman, and that of his other work “Evgeni Onegin.” Originally, Pushkin wanted to continue “Evgeni Onegin” in this narrative, and instead chose to make a new Evgenii, with a different family name but that was still a “caricature of Pushkin’s own character”.[14] Both were descendants of the old regime of Boyars that now found itself socially insignificant in a society where family heritage wasn’t esteemed.

The statue[edit]

The Bronze Horseman of the title was sculpted by Étienne Maurice Falconet and completed in 1782. Catherine the Great, a German princess that married into the Romanov family, commissioned the construction of the statue to legitimize

her rule and claim to the throne to the Russian people. Catherine came to power through an illegal palace coup. She had the statue inscribed with the phrase, Петру перьвому Екатерина вторая, лѣта 1782, in both Latin and Russian, meaning «To Peter the first, from Catherine the second,» to show reverence to the ruler and indicate where she saw her place among Russia’s rulers.

The statue took 12 years to create. It depicts Peter the Great astride his horse, his outstretched arm reaching toward the Neva River in the western part of the country. The statue is lauded for its ambiguity; it is said Pushkin felt the ambiguous message of the statue and was inspired to pen the poem. In a travelogue about Petersburg in 1821, the French statesman Joseph de Maistre commented that he did not know «whether Peter’s bronze hand protects or threatens».[3]

The city of St. Petersburg[edit]

St. Petersburg was built by Peter the Great at the beginning of the 18th century, on the swampy shores and islands of the Neva. The difficulties of construction were numerous, but Peter was unperturbed by the expenditure of human life required to fulfil his vision of a city on the coast. Of the artisans whom he compelled to come north to lay the foundations of the city, thousands died of hardship and disease; and the city, in its unnatural location, was at the mercy of terrible floods caused by the breaking-up of the ice of the Lake Ladoga just east of it or – as on the occasion described in the poem – by the west wind blowing back the Neva. There had been one such devastating flood in 1777 and again in 1824, during Pushkin’s time and the flood modeled in the poem, and they continued until the Saint Petersburg Dam was built.

Themes[edit]

Statue vs. Evgenii[edit]

The conflict between Tsar and citizen, or empire and individual, is a key theme of «The Bronze Horseman».[15] Critics differ as to whether Pushkin ultimately sides with Evgenii — the little man — or Peter and historical necessity. The radical 19th-century critic Vissarion Belinsky considered the poem a vindication of Peter’s policies, while the writer Dmitri Merezhkovsky thought it a poem of individual protest.[16]

Another interpretation of the poem suggests that the statue does not actually come to life, but that Evgenii loses his sanity. Pushkin makes Evgenii go mad to create “a terrifying dimension to even the most humdrum personality and at the same time show the abyss hidden in the most apparently common-place human soul”.[17] In this regard, Evgenii is seen to become a disinherited man of the time in much the same vein as a traditional epic hero.[18]

Perhaps Evgenii is not Peter’s enemy at all. According to Newman, “[Evgenii] is too small for that.”[19] Instead, the heroic conflict of the poem is between Peter the Great and the elements while Evgenii is merely its “impotent victim.»[20] As Evgenii becomes more and more distressed at the disappearance of his fiancée, his increasing anxiety is juxtaposed with the indifference of the ferryman who rows him across the river. Newman thus calls into question whether or not Evgenii is justified in these feelings and how these feelings reflect his non-threatening position in relation to the statue.[7]

Man’s position in relation to nature[edit]

In the very act of conceiving and creating his city in the northern swamps, Peter has imposed order on the primeval natural scene depicted at the beginning of the poem. The city itself, «graceful yet austere» in its classical design, is, as much as the Falconet statue, Peter’s living monument, carrying on his struggle against the «wild, tumultuous» Finnish waves. Its granite banks may hold the unruly elements in check for most of the time, but even they are helpless against such a furious rebellion as the flood of 1824. The waves’ victory is, admittedly, short-lived: the flood soon recedes and the city returns to normal. Even so, it is clear that they can never be decisively defeated; they live to fight another day.

A psychoanalytical reading by Daniel Rancour-Laferriere suggests that there is an underlying concern with couvade syndrome or male birthing in the poem. He argues that the passages of the creation of Petersburg resemble the Greek myth of Zeus giving birth to Athena, and suggests that the flood corresponds to the frequent use of water as a metaphor for birth in many cultures. He suggests that the imagery describing Peter and the Neva is gendered: Peter is male and the Neva female.[21]

Immortality[edit]

Higher authority is represented most clearly by Peter. What is more, he represents it in a way which sets him apart from the mass of humanity and even (so Pushkin hints, as we shall see) from such run-of-the-mill autocrats as Alexander I. Only in the first twenty lines of the poem does Peter appear as a living person. The action then shifts forward abruptly by a hundred years, and the rest of the poem is set in a time when Peter is obviously long since dead. Yet despite this we have a sense throughout of Peter’s living presence, as if he had managed to avoid death in a quite unmortal way. The section evoking contemporary St Petersburg– Peter’s youthful creation, in which his spirit lives on–insinuates the first slight suggestion of this. Then comes a more explicit hint, as Pushkin voices the hope that the Finnish waves will not ‘disturb great Peter’s ageless sleep’. Peter, we must conclude, is not dead after all: he will awake from his sleep if danger should at any time threaten his capital city, the heart of the nation. Peter appears not as an ordinary human being but as an elemental force: he is an agent in the historical process, and even beyond this he participates in a wider cosmic struggle between order and disorder.

Evgenii is accorded equal status with Peter in purely human terms, and his rebellion against state power is shown to be as admirable and significant in its way as that of the Decembrists. Yet turning now to the question of Evgenii’s role in the wider scheme of things, we have to admit that he seems an insignificant third factor in the equation when viewed against the backdrop of the titanic struggle taking place between Peter and the elements. Evgenii is utterly and completely helpless against both. The flood sweeps away all his dreams of happiness, and it is in the river that he meets his death. Peter’s statue, which at their first «encounter» during the flood had its back turned to Evgenii as if ignoring him, late hounds him mercilessly when he dares to protest at Peter’s role in his suffering. The vast, impersonal forces of order and chaos, locked in an unending struggle – these, Pushkin seems to be saying, are the reality: these are the millstones of destiny or of the historical process to which Evgenii and his kind are but so much grist.

Symbolism[edit]

The river[edit]

Peter the Great chose the river and all of its elemental forces as an entity worth combating.[19] Peter «harnesses it, dresses it up, and transforms it into the centerpiece of his imperium.”[22] However, the river cannot be tamed for long. It brings floods to Peter’s orderly city as “It seethes up from below, manifesting itself in uncontrolled passion, illness, and violence. It rebels against order and tradition. It wanders from its natural course.”[23] “Before Peter, the river lived in an uneventful but primeval existence” and though Peter tries to impose order, the river symbolizes what is natural and tries to return to its original state. “The river resembles Evgenii not as an initiator of violence but as a reactant. Peter has imposed his will on the people (Evgenii) and nature (the Neva) as a means of realizing his imperialistic ambitions” [22] and both Evgenii and the river try to break away from the social order and world that Peter has constructed.

The Bronze Horseman[edit]

The Bronze Horseman symbolizes «Tsar Peter, the city of St Petersburg, and the uncanny reach of autocracy over the lives of ordinary people.»[24] When Evgenii threatens the statue, he is threatening “everything distilled in the idea of Petersburg.”[23] At first, Evgenii was just a lowly clerk that the Bronze Horseman could not deign to recognize because Evgenii was so far beneath him. However, when Evgenii challenges him, «Peter engages the world of Evgenii» as a response to Evgenii’s arrogance.[25] The «statue stirs in response to his challenge» and gallops after him to crush his rebellion.[24] Before, Evgenii was just a little man that the Bronze Horseman would not bother to respond to. Upon Evgenii’s challenge, however, he becomes an equal and a rival that the Bronze Horseman must crush in order to protect the accomplishments he stands for.

Soviet analysis[edit]

Alexander Pushkin on Soviet poster

Pushkin’s poem became particularly significant during the Soviet era. Pushkin depicted Peter as a strong leader, so allowing Soviet citizens to praise their own Peter, Joseph Stalin.[26] Stalin himself was said to be “most willingly compared” to Peter the Great.[27] A poll in Literaturnyi sovremennik in March 1936 reported praise for Pushkin’s portrayal of Peter, with comments in favour of how The Bronze Horseman depicted the resolution of the conflict between the personal and the public in favour of the public. This was in keeping with the Stalinist emphasis of how the achievements of Soviet society as a whole were to be extolled over the sufferings of the individual.[26] Soviet thinkers also read deeper meanings into Pushkin’s works. Andrei Platonov wrote two essays to commemorate the centenary of Pushkin’s death, both published in Literaturnyi kritik. In Pushkin, Our Comrade, Platonov expanded upon his view of Pushkin as a prophet of the later rise of socialism.[28] Pushkin not only ‘divined the secret of the people’, wrote Platonov, he depicted it in The Bronze Horseman, where the collision between Peter the Great’s ruthless quest to build an empire, as expressed in the construction of Saint Petersburg, and Evgenii’s quest for personal happiness will eventually come together and be reconciled by the advent of socialism.[28] Josef Brodsky’s A Guide to a Renamed City «shows both Lenin and the Horseman to be equally heartless arbiters of other’s fates,» connecting the work to another great Soviet leader.[29]

Soviet literary critics could however use the poem to subvert those same ideals. In 1937 the Red Archive published a biographical account of Pushkin, written by E. N. Cherniavsky. In it Cherniavsky explained how The Bronze Horseman could be seen as Pushkin’s attack on the repressive nature of the autocracy under Tsar Nicholas I.[26] Having opposed the government and suffered his ruin, Evgenii challenges the symbol of Tsarist authority but is destroyed by its terrible, merciless power.[26] Cherniavsky was perhaps also using the analysis to attack the Soviet system under Stalin. By 1937 the Soviet intelligentsia was faced with many of the same issues that Pushkin’s society had struggled with under Nicholas I.[30] Cherniavsky set out how Evgenii was a symbol for the downtrodden masses throughout Russia. By challenging the statue, Evgenii was challenging the right of the autocracy to rule over the people. Whilst in keeping with Soviet historiography of the late Tsarist period, Cherniavsky subtly hinted at opposition to the supreme power presently ruling Russia.[30] He assessed the resolution of the conflict between the personal and the public with praise for the triumph of socialism, but couched it in terms that left his work open to interpretation, that while openly praising Soviet advances, he was using Pushkin’s poem to criticise the methods by which this was achieved.[30]

Legacy and adaptations[edit]

The work has had enormous influence in Russian culture. The setting of Evgenii’s defiance, Senate Square, was coincidentally also the scene of the Decembrist revolt of 1825.[31] Within the literary realm, Dostoevsky’s The Double: A Petersburg Poem [Двойник] (1846) directly engages with «The Bronze Horseman», treating Evgenii’s madness as parody.[32] The theme of madness parallels many of Gogol’s works and became characteristic of 19th- and 20th-century Russian literature.[17] Andrei Bely’s novel Petersburg [Петербург] (1913; 1922) uses the Bronze Horseman as a metaphor for the centre of power in the city of Petersburg, which is itself a living entity and the main character of Bely’s novel.[33] The bronze horseman, representing Peter the Great, chases the novel’s protagonist, Nikolai Ableukhov. He is thus forced to flee the statue just like Evgenii. In this context, Bely implies that Peter the Great is responsible for Russia’s national identity that is torn between Western and Eastern influences.[29]

Other literary references to the poem include Anna Akmatova’s «Poem Without a Hero», which mentions the Bronze Horseman «first as the thudding of unseen hooves». Later on, the epilogue describes her escape from the pursuing Horseman.[24] In Valerii Briusov’s work “To the Bronze Horseman” published in 1906, the author suggests that the monument is a «representation of eternity, as indifferent to battles and slaughter as it was Evgenii’s curses».[34]

Nikolai Myaskovsky’s 10th Symphony (1926–7) was inspired by the poem.

In 1949 composer Reinhold Glière and choreographer Rostislav Zakharov adapted the poem into a ballet premiered at the Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre in Leningrad. This production was restored, with some changes, by Yuri Smekalov ballet (2016) at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg. The ballet has re-established its place in the Mariinsky repertoire.

References[edit]

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. «Mednyy vsadnik [The Bronze Horseman]». The Literary Encyclopedia. 26 April 2005.accessed 30 November 2008.

- ^ For general comments on the poem’s success and influence, see Binyon, T. J. (2002), Pushkin: A Biography. London: Harper Collins, p. 437; Rosenshield, Gary. (2003), Pushkin and the Genres of Madness. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, p. 91; Cornwell, Neil (ed.) (1998), Reference Guide to Russian Literature. London: Taylor and Francis, p. 677.

- ^ a b See V. Ia. Briusov’s 1929 essay on «The Bronze Horseman», available here (in Russian).

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 91.

- ^ Little, p. xiv.

- ^ Wachtel, Michael. (2006) «Pushkin’s long poems and the epic impulse». In Andrew Kahn (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Puskhin, Cambridge: CUP, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Newman, John Kevin. «Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman and the Epic Tradition.» Comparative Literature Studies 9.2 (1972): p. 187.JSTOR. Penn State University Press.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 190

- ^ a b Wachtel, p. 86.

- ^ Newman, p. 176

- ^ Pushkin’s own footnotes refer to Mickiewicz’s poem ‘Oleskiewicz’ which describe the 1824 flood in Petersburg. See also Little, p. xiii; Binyon, pp. 435–6

- ^ Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ See Binyon, p. 435; Little, p. xiii; Bayley, John (1971), Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 128.

- ^ Wilson, p. 67.

- ^ Little, p. xix; Bayley, p. 131.

- ^ Cited in Banjeree, Maria. (1978) «Pushkin’s ‘The Bronze Horseman’: An Agonistic Vision». Modern Languages Studies, 8, no. 2, Spring, p. 42.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 180.

- ^ Newman, p. 189.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 175,

- ^ Newman, p. 180.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. «The Couvade of Peter the Great: A Psychoanalytic Aspect of The Bronze Horseman», D. Bethea (ed.), Pushkin Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp. 73–85.

- ^ a b Rosenshield, p. 141.

- ^ a b Rosenshield, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Weinstock, p. 60.

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Petrone. Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. p. 143.

- ^ Newman, p. 175.

- ^ a b Debreczany. «»Zhitie Aleksandra Boldinskogo«: Pushkin’s Elevation to Sainthood in Soviet Culture». Late Soviet Culture: From Perestroika to Novostroika. pp. 60–1.

- ^ a b Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew (2014). The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. Central Michigan University. p. 60.

- ^ a b c Petrone. Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. p. 144.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (1938). The Triple Thinkers; Ten Essays on Literature. New York: Harcourt, Brace. p. 71.

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 5.

- ^ Cornwell, p. 160.

- ^ Weinstock, p. 59.

Sources[edit]

- Basker, Michael (ed.), The Bronze Horseman. Bristol Classical Press, 2000

- Binyon, T. J. Pushkin: A Biography. Harper Collins, 2002

- Briggs, A. D. P. Aleksandr Pushkin: A Critical Study. Barnes and Noble, 1982

- Debreczany, Paul (1993). «»Zhitie Aleksandra Boldinskogo«: Pushkin’s Elevation to Sainthood in Soviet Culture». In Lahusen, Thomas; Kuperman, Gene (eds.). Late Soviet Culture: From Perestroika to Novostroika. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1324-3., 1993

- Kahn, Andrew (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Pushkin. Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Kahn, Andrew, Pushkin’s «Bronze Horseman»: Critical Studies in Russian Literature. Bristol Classical Press, 1998

- Little, T. E. (ed.), The Bronze Horseman. Bradda Books, 1974

- Newman, John Kevin. «Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman and the Epic Tradition.» Comparative Literature Studies 9.2 (1972): JSTOR. Penn State University Press

- Petrone, Karen (2000). Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades: Celebrations in the Time of Stalin. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33768-2., 2000

- Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. «The Couvade of Peter the Great: A Psychoanalytic Aspect of The Bronze Horseman», D. Bethea (ed.). Pushkin Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington

- Rosenshield, Gary. Pushkin and the Genres of Madness: The Masterpieces of 1833. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 2003.

- Schenker, Alexander M. The Bronze Horseman: Falconet’s Monument to Peter the Great. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003

- Wachtel, Michael. «Pushkin’s long poems and the epic impulse». In Andrew Kahn (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Puskhin, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew. «The Bronze Horseman.» The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters: Central Michigan University, 2014

- Wilson, Edmund. The Triple Thinkers; Ten Essays on Literature. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1938.

External links[edit]

- (in Russian) The text of The Bronze Horseman at Russian Wikisource

- (in Russian) The Bronze Horseman: Russian Text

- (in Russian) Listen to Russian version of The Bronze Horseman, courtesy of Cornell University

- Information about English translations of the poem

- The Bronze Horseman: an English verse translation

Alexandre Benois’s illustration to the poem (1904). |

|

| Author | Alexander Pushkin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Медный Всадник [Mednyi Vsadnik] |

| Translator | C. E. Turner |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Narrative poem |

| Publisher | Sovremennik |

|

Publication date |

1837 |

|

Published in English |

1882 |

The Bronze Horseman: A Petersburg Tale (Russian: Медный всадник: Петербургская повесть Mednyy vsadnik: Peterburgskaya povest) is a narrative poem written by Alexander Pushkin in 1833 about the equestrian statue of Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg and the great flood of 1824. While the poem was written in 1833, it was not published, in its entirety, until after his death as his work was under censorship due to the political nature of his other writings. Widely considered to be Pushkin’s most successful narrative poem, The Bronze Horseman has had a lasting impact on Russian literature. The Pushkin critic A. D. P. Briggs praises the poem «as the best in the Russian language, and even the best poem written anywhere in the nineteenth century».[1] It is considered one of the most influential works in Russian literature, and is one of the reasons Pushkin is often called the “founder of modern Russian literature.”

The statue became known as The Bronze Horseman due to the great influence of the poem.[2]

Plot summary[edit]

The poem is divided into three sections: a shorter introduction (90 lines) and two longer parts (164 and 222 lines). The introduction opens with a mythologized history of the establishment of the city of Saint Petersburg in 1703. In the first two stanzas, Peter the Great stands at the edge of the River Neva and conceives the idea for a city which will threaten the Swedes and open a «window to Europe». The poem describes the area as almost uninhabited: Peter can only see one boat and a handful of dark houses inhabited by Finnish peasants. Saint Petersburg was in fact constructed on territory newly gained from the Swedes in the Great Northern War, and Peter himself chose the site for the founding of a major city because it provided Russia with a corner of access to the Baltic Sea, and thus to the Atlantic and Europe.

The rest of the introduction is in the first person and reads as an ode to the city of Petersburg. The poet-narrator describes how he loves Petersburg, including the city’s «stern, muscular appearance» (l. 44), its landmarks such as the Admiralty (ll. 50–58), and its harsh winters and long summer evenings (ll. 59 – ll. 84). He encourages the city to retain its beauty and strength and stand firm against the waves of the Neva (ll. 85–91).

Part I opens with an image of the Neva growing rough in a storm: the river is «tossing and turning like a sick man in his troubled bed» (ll. 5–6). Against this backdrop, a young poor man in the city, Evgenii, is contemplating his love for a young woman, Parasha, and planning to spend the rest of his life with her (ll. 49–62). Evgenii falls asleep, and the narrative then turns back to the Neva, with a description of how the river floods and destroys much of the city (ll. 72–104). The frightened and desperate Evgenii is left sitting alone on top of two marble lions on Peter’s Square, surrounded by water and with the Bronze Horseman statue looking down on him (ll. 125–164).

In Part II, Evgenii finds a ferryman and commands him to row to where Parasha’s home used to be (ll. 26 – ll. 56). However, he discovers that her home has been destroyed (ll. 57–60), and falls into a crazed delirium and breaks into laughter (ll. 61–65). For a year, he roams the street as a madman (ll. 89–130), but the following autumn, he is reminded of the night of the storm (ll. 132–133) and the source of his troubles. In a fit of rage, he curses the statue of Peter (ll. 177–179), which brings the statue to life, and Peter begins pursuing Evgenii (ll. 180–196). The narrator does not describe Evgenii’s death directly, but the poem closes with the discovery of his corpse in a ruined hut floating on the water (ll. 219–222).

Genre[edit]

Formally, the poem is an unusual mix of genres: the sections dealing with Tsar Peter are written in a solemn, odic, 18th-century style, while the Evgenii sections are prosaic, playful and, in the latter stages, filled with pathos.[3] This mix of genres is anticipated by the title: «The Bronze Horseman» suggested a grandiose ode, but the subtitle «A Petersburg Tale» leads one to expect an unheroic protagonist[4] Metrically, the entire poem is written in using the four-foot iamb, one of Pushkin’s preferred meters, a versatile form which is able to adapt to the changing mood of the poem. The poem has a varied rhyme scheme and stanzas of varying length.[5]

The critic Michael Watchel has suggested that Pushkin intended to produce a national epic in this poem, arguing that the Peter sections have many of the typical features of epic poetry.[6] He points to Pushkin’s extensive use of Old Testament language and allusions when describing both the founding of St Petersburg and the flood and argues that they draw heavily on the Book of Genesis. Further evidence for the categorization of Pushkin’s poem as an epic can be seen in its rhyme scheme and stanza structure which allow the work to convey its meaning in a very concise yet artistic manner.[7] Another parallel to the classical epic tradition can be drawn in the final scenes of Evgenii’s burial described as “for God’s sake.” In Russian, this phrase is not one of “chafing impatience, but of the kind of appeal to Christian sentiment which a beggar might make” according to Newman.[8] Therefore, it is a lack of empathy and charity in Petersburg that ultimately causes Evgenii’s death. The requirement that civilization must have a moral order is a theme also found in the writings of Virgil.[8] However, he adds that the Evgenii plot runs counter to the epic mode, and praises Pushkin for his «remarkable ability to synthesize diverse materials, styles and genres».[9] What is particularly unusual is that Pushkin focuses on a protagonist that is humble as well as one that is ostensibly great. There are more questions than answers in this new type of epic, where “an agnostic irony can easily find a place” while “the unbiased reader would be forced to recognize as concerned with the profoundest issues which confront humanity”.[10] He concludes that if the poem is to be labeled a national epic, it is a «highly idiosyncratic» one.[9]

Historical and cultural context[edit]

Several critics have suggested that the immediate inspiration for «The Bronze Horseman» was the work of the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz.[11][12] Before beginning work on «The Bronze Horseman», Pushkin had read Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve (1823–32), which contains a poem entitled «To My Muscovite Friends», a thinly-veiled attack on Pushkin and Vasily Zhukovsky for their failure to join the radical Decembrist revolt of 1825. Forefather’s Eve contains poems where Peter I is described as a despot who created the city because of autocratic whim, and a poem mocks the Falconet statue as looking as though he is about to jump off a precipice. Pushkin’s poem can be read in part as a retort to Mickiewicz, although most critics agree that its concerns are much broader than answering a political enemy.[13]

There are distinct similarities between Pushkin’s protagonist in The Bronze Horseman, and that of his other work “Evgeni Onegin.” Originally, Pushkin wanted to continue “Evgeni Onegin” in this narrative, and instead chose to make a new Evgenii, with a different family name but that was still a “caricature of Pushkin’s own character”.[14] Both were descendants of the old regime of Boyars that now found itself socially insignificant in a society where family heritage wasn’t esteemed.

The statue[edit]

The Bronze Horseman of the title was sculpted by Étienne Maurice Falconet and completed in 1782. Catherine the Great, a German princess that married into the Romanov family, commissioned the construction of the statue to legitimize

her rule and claim to the throne to the Russian people. Catherine came to power through an illegal palace coup. She had the statue inscribed with the phrase, Петру перьвому Екатерина вторая, лѣта 1782, in both Latin and Russian, meaning «To Peter the first, from Catherine the second,» to show reverence to the ruler and indicate where she saw her place among Russia’s rulers.

The statue took 12 years to create. It depicts Peter the Great astride his horse, his outstretched arm reaching toward the Neva River in the western part of the country. The statue is lauded for its ambiguity; it is said Pushkin felt the ambiguous message of the statue and was inspired to pen the poem. In a travelogue about Petersburg in 1821, the French statesman Joseph de Maistre commented that he did not know «whether Peter’s bronze hand protects or threatens».[3]

The city of St. Petersburg[edit]

St. Petersburg was built by Peter the Great at the beginning of the 18th century, on the swampy shores and islands of the Neva. The difficulties of construction were numerous, but Peter was unperturbed by the expenditure of human life required to fulfil his vision of a city on the coast. Of the artisans whom he compelled to come north to lay the foundations of the city, thousands died of hardship and disease; and the city, in its unnatural location, was at the mercy of terrible floods caused by the breaking-up of the ice of the Lake Ladoga just east of it or – as on the occasion described in the poem – by the west wind blowing back the Neva. There had been one such devastating flood in 1777 and again in 1824, during Pushkin’s time and the flood modeled in the poem, and they continued until the Saint Petersburg Dam was built.

Themes[edit]

Statue vs. Evgenii[edit]

The conflict between Tsar and citizen, or empire and individual, is a key theme of «The Bronze Horseman».[15] Critics differ as to whether Pushkin ultimately sides with Evgenii — the little man — or Peter and historical necessity. The radical 19th-century critic Vissarion Belinsky considered the poem a vindication of Peter’s policies, while the writer Dmitri Merezhkovsky thought it a poem of individual protest.[16]

Another interpretation of the poem suggests that the statue does not actually come to life, but that Evgenii loses his sanity. Pushkin makes Evgenii go mad to create “a terrifying dimension to even the most humdrum personality and at the same time show the abyss hidden in the most apparently common-place human soul”.[17] In this regard, Evgenii is seen to become a disinherited man of the time in much the same vein as a traditional epic hero.[18]

Perhaps Evgenii is not Peter’s enemy at all. According to Newman, “[Evgenii] is too small for that.”[19] Instead, the heroic conflict of the poem is between Peter the Great and the elements while Evgenii is merely its “impotent victim.»[20] As Evgenii becomes more and more distressed at the disappearance of his fiancée, his increasing anxiety is juxtaposed with the indifference of the ferryman who rows him across the river. Newman thus calls into question whether or not Evgenii is justified in these feelings and how these feelings reflect his non-threatening position in relation to the statue.[7]

Man’s position in relation to nature[edit]

In the very act of conceiving and creating his city in the northern swamps, Peter has imposed order on the primeval natural scene depicted at the beginning of the poem. The city itself, «graceful yet austere» in its classical design, is, as much as the Falconet statue, Peter’s living monument, carrying on his struggle against the «wild, tumultuous» Finnish waves. Its granite banks may hold the unruly elements in check for most of the time, but even they are helpless against such a furious rebellion as the flood of 1824. The waves’ victory is, admittedly, short-lived: the flood soon recedes and the city returns to normal. Even so, it is clear that they can never be decisively defeated; they live to fight another day.

A psychoanalytical reading by Daniel Rancour-Laferriere suggests that there is an underlying concern with couvade syndrome or male birthing in the poem. He argues that the passages of the creation of Petersburg resemble the Greek myth of Zeus giving birth to Athena, and suggests that the flood corresponds to the frequent use of water as a metaphor for birth in many cultures. He suggests that the imagery describing Peter and the Neva is gendered: Peter is male and the Neva female.[21]

Immortality[edit]

Higher authority is represented most clearly by Peter. What is more, he represents it in a way which sets him apart from the mass of humanity and even (so Pushkin hints, as we shall see) from such run-of-the-mill autocrats as Alexander I. Only in the first twenty lines of the poem does Peter appear as a living person. The action then shifts forward abruptly by a hundred years, and the rest of the poem is set in a time when Peter is obviously long since dead. Yet despite this we have a sense throughout of Peter’s living presence, as if he had managed to avoid death in a quite unmortal way. The section evoking contemporary St Petersburg– Peter’s youthful creation, in which his spirit lives on–insinuates the first slight suggestion of this. Then comes a more explicit hint, as Pushkin voices the hope that the Finnish waves will not ‘disturb great Peter’s ageless sleep’. Peter, we must conclude, is not dead after all: he will awake from his sleep if danger should at any time threaten his capital city, the heart of the nation. Peter appears not as an ordinary human being but as an elemental force: he is an agent in the historical process, and even beyond this he participates in a wider cosmic struggle between order and disorder.

Evgenii is accorded equal status with Peter in purely human terms, and his rebellion against state power is shown to be as admirable and significant in its way as that of the Decembrists. Yet turning now to the question of Evgenii’s role in the wider scheme of things, we have to admit that he seems an insignificant third factor in the equation when viewed against the backdrop of the titanic struggle taking place between Peter and the elements. Evgenii is utterly and completely helpless against both. The flood sweeps away all his dreams of happiness, and it is in the river that he meets his death. Peter’s statue, which at their first «encounter» during the flood had its back turned to Evgenii as if ignoring him, late hounds him mercilessly when he dares to protest at Peter’s role in his suffering. The vast, impersonal forces of order and chaos, locked in an unending struggle – these, Pushkin seems to be saying, are the reality: these are the millstones of destiny or of the historical process to which Evgenii and his kind are but so much grist.

Symbolism[edit]

The river[edit]

Peter the Great chose the river and all of its elemental forces as an entity worth combating.[19] Peter «harnesses it, dresses it up, and transforms it into the centerpiece of his imperium.”[22] However, the river cannot be tamed for long. It brings floods to Peter’s orderly city as “It seethes up from below, manifesting itself in uncontrolled passion, illness, and violence. It rebels against order and tradition. It wanders from its natural course.”[23] “Before Peter, the river lived in an uneventful but primeval existence” and though Peter tries to impose order, the river symbolizes what is natural and tries to return to its original state. “The river resembles Evgenii not as an initiator of violence but as a reactant. Peter has imposed his will on the people (Evgenii) and nature (the Neva) as a means of realizing his imperialistic ambitions” [22] and both Evgenii and the river try to break away from the social order and world that Peter has constructed.

The Bronze Horseman[edit]

The Bronze Horseman symbolizes «Tsar Peter, the city of St Petersburg, and the uncanny reach of autocracy over the lives of ordinary people.»[24] When Evgenii threatens the statue, he is threatening “everything distilled in the idea of Petersburg.”[23] At first, Evgenii was just a lowly clerk that the Bronze Horseman could not deign to recognize because Evgenii was so far beneath him. However, when Evgenii challenges him, «Peter engages the world of Evgenii» as a response to Evgenii’s arrogance.[25] The «statue stirs in response to his challenge» and gallops after him to crush his rebellion.[24] Before, Evgenii was just a little man that the Bronze Horseman would not bother to respond to. Upon Evgenii’s challenge, however, he becomes an equal and a rival that the Bronze Horseman must crush in order to protect the accomplishments he stands for.

Soviet analysis[edit]

Alexander Pushkin on Soviet poster

Pushkin’s poem became particularly significant during the Soviet era. Pushkin depicted Peter as a strong leader, so allowing Soviet citizens to praise their own Peter, Joseph Stalin.[26] Stalin himself was said to be “most willingly compared” to Peter the Great.[27] A poll in Literaturnyi sovremennik in March 1936 reported praise for Pushkin’s portrayal of Peter, with comments in favour of how The Bronze Horseman depicted the resolution of the conflict between the personal and the public in favour of the public. This was in keeping with the Stalinist emphasis of how the achievements of Soviet society as a whole were to be extolled over the sufferings of the individual.[26] Soviet thinkers also read deeper meanings into Pushkin’s works. Andrei Platonov wrote two essays to commemorate the centenary of Pushkin’s death, both published in Literaturnyi kritik. In Pushkin, Our Comrade, Platonov expanded upon his view of Pushkin as a prophet of the later rise of socialism.[28] Pushkin not only ‘divined the secret of the people’, wrote Platonov, he depicted it in The Bronze Horseman, where the collision between Peter the Great’s ruthless quest to build an empire, as expressed in the construction of Saint Petersburg, and Evgenii’s quest for personal happiness will eventually come together and be reconciled by the advent of socialism.[28] Josef Brodsky’s A Guide to a Renamed City «shows both Lenin and the Horseman to be equally heartless arbiters of other’s fates,» connecting the work to another great Soviet leader.[29]

Soviet literary critics could however use the poem to subvert those same ideals. In 1937 the Red Archive published a biographical account of Pushkin, written by E. N. Cherniavsky. In it Cherniavsky explained how The Bronze Horseman could be seen as Pushkin’s attack on the repressive nature of the autocracy under Tsar Nicholas I.[26] Having opposed the government and suffered his ruin, Evgenii challenges the symbol of Tsarist authority but is destroyed by its terrible, merciless power.[26] Cherniavsky was perhaps also using the analysis to attack the Soviet system under Stalin. By 1937 the Soviet intelligentsia was faced with many of the same issues that Pushkin’s society had struggled with under Nicholas I.[30] Cherniavsky set out how Evgenii was a symbol for the downtrodden masses throughout Russia. By challenging the statue, Evgenii was challenging the right of the autocracy to rule over the people. Whilst in keeping with Soviet historiography of the late Tsarist period, Cherniavsky subtly hinted at opposition to the supreme power presently ruling Russia.[30] He assessed the resolution of the conflict between the personal and the public with praise for the triumph of socialism, but couched it in terms that left his work open to interpretation, that while openly praising Soviet advances, he was using Pushkin’s poem to criticise the methods by which this was achieved.[30]

Legacy and adaptations[edit]

The work has had enormous influence in Russian culture. The setting of Evgenii’s defiance, Senate Square, was coincidentally also the scene of the Decembrist revolt of 1825.[31] Within the literary realm, Dostoevsky’s The Double: A Petersburg Poem [Двойник] (1846) directly engages with «The Bronze Horseman», treating Evgenii’s madness as parody.[32] The theme of madness parallels many of Gogol’s works and became characteristic of 19th- and 20th-century Russian literature.[17] Andrei Bely’s novel Petersburg [Петербург] (1913; 1922) uses the Bronze Horseman as a metaphor for the centre of power in the city of Petersburg, which is itself a living entity and the main character of Bely’s novel.[33] The bronze horseman, representing Peter the Great, chases the novel’s protagonist, Nikolai Ableukhov. He is thus forced to flee the statue just like Evgenii. In this context, Bely implies that Peter the Great is responsible for Russia’s national identity that is torn between Western and Eastern influences.[29]

Other literary references to the poem include Anna Akmatova’s «Poem Without a Hero», which mentions the Bronze Horseman «first as the thudding of unseen hooves». Later on, the epilogue describes her escape from the pursuing Horseman.[24] In Valerii Briusov’s work “To the Bronze Horseman” published in 1906, the author suggests that the monument is a «representation of eternity, as indifferent to battles and slaughter as it was Evgenii’s curses».[34]

Nikolai Myaskovsky’s 10th Symphony (1926–7) was inspired by the poem.

In 1949 composer Reinhold Glière and choreographer Rostislav Zakharov adapted the poem into a ballet premiered at the Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre in Leningrad. This production was restored, with some changes, by Yuri Smekalov ballet (2016) at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg. The ballet has re-established its place in the Mariinsky repertoire.

References[edit]

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. «Mednyy vsadnik [The Bronze Horseman]». The Literary Encyclopedia. 26 April 2005.accessed 30 November 2008.

- ^ For general comments on the poem’s success and influence, see Binyon, T. J. (2002), Pushkin: A Biography. London: Harper Collins, p. 437; Rosenshield, Gary. (2003), Pushkin and the Genres of Madness. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, p. 91; Cornwell, Neil (ed.) (1998), Reference Guide to Russian Literature. London: Taylor and Francis, p. 677.

- ^ a b See V. Ia. Briusov’s 1929 essay on «The Bronze Horseman», available here (in Russian).

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 91.

- ^ Little, p. xiv.

- ^ Wachtel, Michael. (2006) «Pushkin’s long poems and the epic impulse». In Andrew Kahn (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Puskhin, Cambridge: CUP, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Newman, John Kevin. «Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman and the Epic Tradition.» Comparative Literature Studies 9.2 (1972): p. 187.JSTOR. Penn State University Press.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 190

- ^ a b Wachtel, p. 86.

- ^ Newman, p. 176

- ^ Pushkin’s own footnotes refer to Mickiewicz’s poem ‘Oleskiewicz’ which describe the 1824 flood in Petersburg. See also Little, p. xiii; Binyon, pp. 435–6

- ^ Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ See Binyon, p. 435; Little, p. xiii; Bayley, John (1971), Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 128.

- ^ Wilson, p. 67.

- ^ Little, p. xix; Bayley, p. 131.

- ^ Cited in Banjeree, Maria. (1978) «Pushkin’s ‘The Bronze Horseman’: An Agonistic Vision». Modern Languages Studies, 8, no. 2, Spring, p. 42.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 180.

- ^ Newman, p. 189.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 175,

- ^ Newman, p. 180.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. «The Couvade of Peter the Great: A Psychoanalytic Aspect of The Bronze Horseman», D. Bethea (ed.), Pushkin Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp. 73–85.

- ^ a b Rosenshield, p. 141.

- ^ a b Rosenshield, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Weinstock, p. 60.

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Petrone. Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. p. 143.

- ^ Newman, p. 175.

- ^ a b Debreczany. «»Zhitie Aleksandra Boldinskogo«: Pushkin’s Elevation to Sainthood in Soviet Culture». Late Soviet Culture: From Perestroika to Novostroika. pp. 60–1.

- ^ a b Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew (2014). The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. Central Michigan University. p. 60.

- ^ a b c Petrone. Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. p. 144.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (1938). The Triple Thinkers; Ten Essays on Literature. New York: Harcourt, Brace. p. 71.

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 5.

- ^ Cornwell, p. 160.

- ^ Weinstock, p. 59.

Sources[edit]

- Basker, Michael (ed.), The Bronze Horseman. Bristol Classical Press, 2000

- Binyon, T. J. Pushkin: A Biography. Harper Collins, 2002

- Briggs, A. D. P. Aleksandr Pushkin: A Critical Study. Barnes and Noble, 1982

- Debreczany, Paul (1993). «»Zhitie Aleksandra Boldinskogo«: Pushkin’s Elevation to Sainthood in Soviet Culture». In Lahusen, Thomas; Kuperman, Gene (eds.). Late Soviet Culture: From Perestroika to Novostroika. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1324-3., 1993

- Kahn, Andrew (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Pushkin. Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Kahn, Andrew, Pushkin’s «Bronze Horseman»: Critical Studies in Russian Literature. Bristol Classical Press, 1998

- Little, T. E. (ed.), The Bronze Horseman. Bradda Books, 1974

- Newman, John Kevin. «Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman and the Epic Tradition.» Comparative Literature Studies 9.2 (1972): JSTOR. Penn State University Press

- Petrone, Karen (2000). Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades: Celebrations in the Time of Stalin. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33768-2., 2000

- Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. «The Couvade of Peter the Great: A Psychoanalytic Aspect of The Bronze Horseman», D. Bethea (ed.). Pushkin Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington

- Rosenshield, Gary. Pushkin and the Genres of Madness: The Masterpieces of 1833. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 2003.

- Schenker, Alexander M. The Bronze Horseman: Falconet’s Monument to Peter the Great. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003

- Wachtel, Michael. «Pushkin’s long poems and the epic impulse». In Andrew Kahn (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Puskhin, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew. «The Bronze Horseman.» The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters: Central Michigan University, 2014