- Сочинения

- По литературе

- Другие

- Анализ сказки Кот в сапогах Перро

Анализ сказки Кот в сапогах Перро

Сказка Кот в сапогах написана французским писателем Шарлем Перро в XVII веке.

Действие начинается с раздела имущества в семье мельника. Старшему сыну досталась мельница, среднему — осел, а самому младшему — рыжий кот.

Младший брат, Ганс, переживал и не знал, что ему с этим котом делать. Питомец сам спас ситуацию и попросил своего хозяина купить ему сапоги.

С тех пор младший сын дружно жил с котом. Кот обладал хитростью и сообразительностью. Например, когда хозяин купается в реке, рядом проезжал экипаж правителя. Кот обманул знатного вельможу и сказал, что Ганс — знаменитый маркиз де Карабас. Слуги короля сразу кинулись спасать его. Они одели его В дорогие одежды, усадили в карету. Далее Ганс действительно стал маркизом и женился на дочке короля.

Другой удачный случай. Кот при встрече со страшным людоедом попросил его превратиться в обыкновенную мышь, которую сразу же съел.

В этом произведении поднимается сразу несколько проблем. Во-первых, проблема зависти. Сказка учит тому, что не стоит завидовать тому, у кого больше материальных благ. Если использовать небольшой ресурс с умом, то можно добиться намного больше, чем если использовать большой ресурс без ума. Произведение устанавливает, что сообразительность, ловкость, хитрость, ум — вот те качества, которые нужно в себе развивать, чтобы многого добиться.

Например, Ганс извлек из рыжего кота больше пользы, чем его старший брат из мельницы и средний из осла.

Во-вторых, это проблема преданности. Кот был верен своему хозяину и никогда не бросал его. Он делал все, чтобы ему помочь, быть полезным. Питомец делал это безвозмездно, от души, из-за своей духовной потребности.

Конечно же, сказка «Кот в сапогах» была написана для взрослых. В ней содержится сложный исторический смысл и сатирическое высмеивание правил и норм жизнь общества Франции XVII столетия. В то время многие высокие должны занимали люди, которые не обладали для этого подходящей подготовкой. Они назначались по знакомству, по обряду местничества. Таким образом, многие способные люди не могли пробиться. А каким должен быть этот способный человек? Шарль Перро выразил свой идеал такого человека в образе кота.

2 вариант

Сказка «Кот в сапогах» написана известным во всем мире писателем-сказочником Шарлем Перро. Он придал своему творению глубоко философский фильм, поэтому не является удивительным тот факт, что сказка пользуется широкой популярностью среди детей школьного и дошкольного возраста и в сегодняшние дни. Краткий анализ данной замечательной сказки представлен в этой статье. Именно это литературное произведение следует принять во внимание не только малышам, но и тем, кто занимается в данный момент поиском работы, которая смогла бы приносить большие деньги. Ведь главный герой – Кот- является прекраснейшим примером отличного работника менеджмента или пиар-компании, или рекламы.

Итак, главный герой – это младший сын мельника, который в предвкушении своей близкой смерти раздал детям (трем сыновьям) наследство. Младший сын, по его мнению, остался обделенным. Ведь в отличие от старшего брата, который получил в наследство мельницу, он заслужил всего лишь какого-то кота…

Но парень напрасно печалился, так как именно кот помог ему осуществить в жизнь те вещи, о которых он даже не мечтал. Например, к концу произведения молодой человек становится зятем короля, женясь на его дочери-принцессе. И все это произошло благодаря усердной работе непосредственно кота.

Кот попросил у своего хозяина купить ему сапоги, дабы он смог решать всякие вопросы и выглядел солидно, серьезно, основательно. Хозяин послушался свое животное, хотя не верил в успех его уверений. А зря. Кот оказался, как нельзя, кстати.

А вопросов много смог решить «всего лишь кот». Именно благодаря своей хорошей работе ему удалось поднять своего хозяина в глазах многих людей (в том числе короля). Сначала он получил замок людоеда благодаря своей кошачьей хитрости проворности, потом подкупил выпивкой косцов, чтобы те сказали проезжающему мимо королю, что эти поля принадлежат хозяину. Таким образом, благодаря хорошей работе кота простой крестьянин стал ни кем иным, как маркизом, а потом уже и принцем…

Данная сказка, несмотря на время своего написания, отлично передает мысль, что работа хорошего рекламного менеджера может сыграть великую роль в формировании какой-то личности, точнее – образа и имиджа этой личности. Даже во времена Короля-Солнца сказочники прекрасно понимали эту идею и пытались донести ее через свое творчество в массы.

Анализ 3

Главным персонажем произведения является кот, который достается в наследство младшему сыну старого мельника маркизу Карабасу.

Находясь на смертном одре, мельник делит имеющееся у него имущество между тремя сыновьями, при этом старшему достается мельница, средний сын получает осла, а младший оказывается лишь с котом, сильно разочаровавшись своей наследственной долей, поскольку находит в бедственном положении.

Однако кот оказывается неунывающим и просит у нового хозяина предоставить ему мешок и сапоги. Как только юноша выделяет коту все, что он хотел, последний отправляется на охоту и возвращается с добычей в виде кроликов, которых отправляет в королевский замок в качестве подарков, преподнесенных королю маркизом Карабасом. В течение месяца кот охотится в лесу на кроликов и куропаток, которые потом дарятся королю от имени маркиза.

Затем кот узнает о прогулке короля и принцессы и заставляет хозяина в это время искупаться в озере. Как только карета приближается к водоему, кот начинает громко звать на помощь тонущему маркизу Карабасу и представляет ситуацию в таком свете, что маркиз, якобы, оказывается ограбленным. Его величество, естественно, повелевает одеть маркиза Карабаса в лучшие наряды и приглашает молодого человека в свою карету, где знакомит со своей наследницей.

Изворотливый кот же в это время бежит впереди королевской процессии и велит местным жителям представлять королю все окрестные поля и луга собственностью маркиза. Король находится в шоке от имеющегося богатства маркиза.

Пока хозяин и король наслаждаются прогулкой, кот, понимая, что у богатого маркиза должен быть добротный дом, отправляется в замок, в котором проживает людоед. С помощью хитрости кот одурачивает людоеда, заставив на спор превратиться в мышь, а когда тот становится маленьким животным, проглатывает его.

По прибытии к замку королевской свиты хитрый кот объявляет замок владениями маркиза Карабаса. Ошарашенный роскошными комнатами король сразу же дает согласие на брак своей дочери, принцессы с маркизом Карабасом, а верный кот остается жить вместе со своим хозяином в замке людоеда.

Произведение демонстрирует возможность выхода из любой жизненной ситуации путем проявления ума и смекалки, помогающих в достижении поставленных целей.

Образ кота является примером преданности, верности и дружбы, способных преодолеть неудачи и тяготы жизни.

Также читают:

Картинка к сочинению Анализ сказки Кот в сапогах Перро

Популярные сегодня темы

- Главные герои повести Шинель Гоголя (характеристика)

В сборнике Петербургские повести громко заявлена тема»маленького человека». Таков Акакий Акакиевич Башмачкин, главный герой повести «Шинель», входящей в цикл о Петербурге и мелких чиновниках, его населяющих.

- Главные герои рассказа Старуха Изергиль (характеристика персонажей Горького)

Замечательная повесть, написанная известнейшим русским писателем Максимом Горьким, называется «Старуха Изергиль». Главные герои данного горьковского творения люди уникальные

- Сочинение Черты реализма в романе Герой нашего времени Лермонтова

Роман Лермонтова «Герой нашего времени» является своего рода связующим звеном между двумя литературными направлениями: романтизмом и реализмом. Он является своеобразным переходом между данными направлениями

- Встреча Чичикова с Ноздревым в трактире анализ эпизода сочинение

Один из главных моментов произведения – встреча Чичикова и Ноздрева в трактире. Этот момент имеет огромную роль в анализе читателем характеров главных героев и их замыслов.

- Письмо Васютке из рассказа Васюткино озеро 5 класс

Васютка, привет! Как ты там поживаешь на лоне природы? У вас там такая красота – леса густые, реки мощные, просторы тайги! Хорошо, что летом была возможность гулять по такой прекрасной природе. Каникулы и у меня очень быстро пролетели…

10

Из сказки Кот в сапогах 1 вопрос К какому виду относится сказка 2 вопрос Сколько сыновей было у мельника 3 вопрос Что каму досталось по наследству 4 вопрос Что младший сын собрался сделать с котом 5 вопрос Что попросил кот у хозяенно 6 вопрос Кого кот поймал в лесу 7 вопррс Куда он отправился со своей добычей 8 вопрос Какое имя дал кот своему хозяину 9 вопрос Что потом приносил кот королю 10 вопрос Как хозяен кота оказался в королевской карете 11 вопрос О чем кот просил крестьян и жнецов 12 вопрос Как кот обхетрил людоеда 13 вопрос Чему закончилась сказка 14 вопрос Чему учит сказка 15 вопрос Составь план сказки 16 вопрос Подбери пословицу к сказке.

1 ответ:

0

0

1. волшебная сказка

2. 3 сына

3. старшему-мельница, среднему-осёл, младшему-кот

4. съесть и сделать из шкуры муфту

5. мешок и пару сапог

6. кролика

7. во дворец

8. маркиз де Карабас

9. две куропатки

10. по приглашению короля после его(хозяина) спасения

11. что бы все говорили что все луга и поля собственность Маркиза де Карабаса

12. кот попросил великана превратиться в маленькую мышь, а после того как он это сделал кот его съел

13. Маркиз женился на принцессе, а кот стал знатным вельможей и охотился на мышей в замке

а дальше это от вас зависит, у всех своё мнение

Читайте также

Морж-морЖиха,арбуз-арбуЗы,шкаф-шкаФы,гриб-гриБок,хлеб- хлеБушек.

В парке есть один голубю,которого я всегда кормлю.

Сегодня папа купил большой арбуз на рынке!!

Наконец-то пришла весна! После долгой и снежной зимы приятно выйти во двор и вдохнуть запах теплого ветра, увидеть первых весенних птиц. Не успел сойти последний снег, а сквозь прошлогоднюю траву пробивается молодая зелень. Тоненькие росточки упорно тянутся к солнцу. Вскоре все покроется зеленым ковром. Почки на тополях и березах набухли, в воздухе чувствуется едва уловимый запах клейких листочков. Еще день-два, и деревья покроются нежной зеленью. Вначале это чуть заметный налет, а потом листья начинают расти все смелее и смелее, увеличиваются почти на глазах. Еще мгновение — и деревья оденутся в пышные кроны. Зеленый цвет сменят бледность зимы. Весной по-особенному светит солнце: как-то ослепительно, радостно и празднично. Хочется ходить по улице и улыбаться всем подряд. Не только природа наряжается в яркие краски. Люди тоже скинули с себя теплые шубы и пальто. Вокруг все в красивых и веселых нарядах. Все рады приходу весны!

Возьми — глагол, неопр.ф. (что сделать?) взять.

Пост.признаки: соверш.вид, переходный, 1-е спр.

Непост. признаки: повелит. накл., ед.ч., 2-е лицо.

Недужный- это тот , кто испытывает недомогание, хворает

Съела, подъезд, объеду, объем.

| «Puss in Boots» | |

|---|---|

| by Giovanni Francesco Straparola Giambattista Basile Charles Perrault |

|

Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer |

|

| Country | Italy (1550–1553) France (1697) |

| Language | Italian (originally) |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

«Puss in Boots» (Italian: Il gatto con gli stivali) is an Italian[1][2] fairy tale, later spread throughout the rest of Europe, about an anthropomorphic cat who uses trickery and deceit to gain power, wealth, and the hand of a princess in marriage for his penniless and low-born master.

The oldest written telling is by Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola, who included it in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–1553) in XIV–XV. Another version was published in 1634 by Giambattista Basile with the title Cagliuso, and a tale was written in French at the close of the seventeenth century by Charles Perrault (1628–1703), a retired civil servant and member of the Académie française. There is a version written by Girolamo Morlini, from whom Straparola used various tales in The Facetious Nights of Straparola.[3] The tale appeared in a handwritten and illustrated manuscript two years before its 1697 publication by Barbin in a collection of eight fairy tales by Perrault called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[4][5] The book was an instant success and remains popular.[3]

Perrault’s Histoires has had considerable impact on world culture. The original Italian title of the first edition was Costantino Fortunato, but was later known as Il gatto con gli stivali (lit. The cat with the boots); the French title was «Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités» with the subtitle «Les Contes de ma mère l’Oye» («Stories or Fairy Tales from Past Times with Morals», subtitled «Mother Goose Tales»). The frontispiece to the earliest English editions depicts an old woman telling tales to a group of children beneath a placard inscribed «MOTHER GOOSE’S TALES» and is credited with launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4]

«Puss in Boots» has provided inspiration for composers, choreographers, and other artists over the centuries. The cat appears in the third act pas de caractère of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty,[6] appears in the sequels and self-titled Shrek movie to the animated film Shrek and is signified in the logo of Japanese anime studio Toei Animation. Puss in Boots is also a popular pantomime in the UK.

Plot[edit]

The tale opens with the third and youngest son of a miller receiving his inheritance — a cat. At first, the youngest son laments, as the eldest brother gains their father’s mill, and the middle brother gets the mule-and-cart. However, the feline is no ordinary cat, but one who requests and receives a pair of boots. Determined to make his master’s fortune, the cat bags a rabbit in the forest and presents it to the king as a gift from his master, the fictional Marquis of Carabas. The cat continues making gifts of game to the king for several months, for which he is rewarded.

Puss meets the ogre in a nineteenth-century illustration by Gustave Doré

One day, the king decides to take a drive with his daughter. The cat persuades his master to remove his clothes and enter the river which their carriage passes. The cat disposes of his master’s clothing beneath a rock. As the royal coach nears, the cat begins calling for help in great distress. When the king stops to investigate, the cat tells him that his master the Marquis has been bathing in the river and robbed of his clothing. The king has the young man brought from the river, dressed in a splendid suit of clothes, and seated in the coach with his daughter, who falls in love with him at once.

The cat hurries ahead of the coach, ordering the country folk along the road to tell the king that the land belongs to the «Marquis of Carabas», saying that if they do not he will cut them into mincemeat. The cat then happens upon a castle inhabited by an ogre who is capable of transforming himself into a number of creatures. The ogre displays his ability by changing into a lion, frightening the cat, who then tricks the ogre into changing into a mouse. The cat then pounces upon the mouse and devours it. The king arrives at the castle that formerly belonged to the ogre, and impressed with the bogus Marquis and his estate, gives the lad the princess in marriage. Thereafter; the cat enjoys life as a great lord who runs after mice only for his own amusement.[7]

The tale is followed immediately by two morals; «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie and savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess».[8] The Italian translation by Carlo Collodi notes that the tale gives useful advice if you happen to be a cat or a Marquis of Carabas.

This is the theme in France, but other versions of this theme exist in Asia, Africa, and South America.[9]

Background[edit]

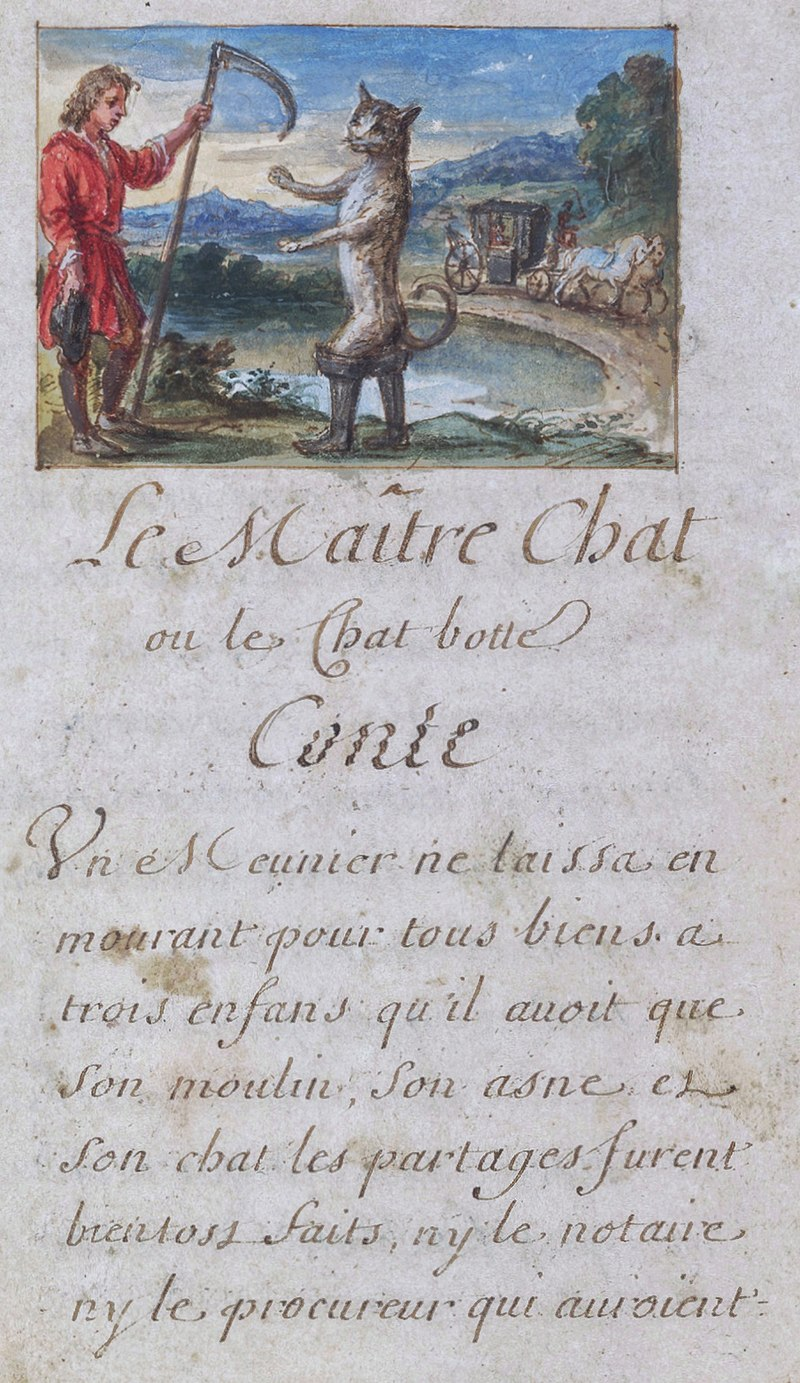

Handwritten and illustrated manuscript of Perrault’s «Le Maître Chat» dated 1695

Perrault’s the «Master Cat or Puss in Boots» is the most renowned tale in all of Western folklore of the animal as helper.[10] However, the trickster cat did not originate with Perrault.[11] Centuries before the publication of Perrault’s tale, Somadeva, a Kashmir Brahmin, assembled a vast collection of Indian folk tales called Kathā Sarit Sāgara (lit. «The ocean of the streams of stories») that featured stock fairy tale characters and trappings such as invincible swords, vessels that replenish their contents, and helpful animals. In the Panchatantra (lit. «Five Principles»), a collection of Hindu tales from the second century BC., a tale follows a cat who fares much less well than Perrault’s Puss as he attempts to make his fortune in a king’s palace.[12]

In 1553, «Costantino Fortunato», a tale similar to «Le Maître Chat», was published in Venice in Giovanni Francesco Straparola’s Le Piacevoli Notti (lit. The Facetious Nights),[13] the first European storybook to include fairy tales.[14] In Straparola’s tale however, the poor young man is the son of a Bohemian woman, the cat is a fairy in disguise, the princess is named Elisetta, and the castle belongs not to an ogre but to a lord who conveniently perishes in an accident. The poor young man eventually becomes King of Bohemia.[13] An edition of Straparola was published in France in 1560.[10] The abundance of oral versions after Straparola’s tale may indicate an oral source to the tale; it also is possible Straparola invented the story.[15]

In 1634, another tale with a trickster cat as hero was published in Giambattista Basile’s collection Pentamerone although neither the collection nor the tale were published in France during Perrault’s lifetime. In Basile’s version, the lad is a beggar boy called Gagliuso (sometimes Cagliuso) whose fortunes are achieved in a manner similar to Perrault’s Puss. However, the tale ends with Cagliuso, in gratitude to the cat, promising the feline a gold coffin upon his death. Three days later, the cat decides to test Gagliuso by pretending to be dead and is mortified to hear Gagliuso tell his wife to take the dead cat by its paws and throw it out the window. The cat leaps up, demanding to know whether this was his promised reward for helping the beggar boy to a better life. The cat then rushes away, leaving his master to fend for himself.[13] In another rendition, the cat performs acts of bravery, then a fairy comes and turns him to his normal state to be with other cats.

It is likely that Perrault was aware of the Straparola tale, since ‘Facetious Nights’ was translated into French in the sixteenth century and subsequently passed into the oral tradition.[3]

Publication[edit]

The oldest record of written history was published in Venice by the Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–53) in XIV-XV. His original title was Costantino Fortunato (lit. Lucky Costantino).

The story was published under the French title Le Maître Chat, ou le Chat Botté (‘Master Cat, or the Booted Cat’) by Barbin in Paris in January 1697 in a collection of tales called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[3] The collection included «La Belle au bois dormant» («The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood»), «Le petit chaperon rouge» («Little Red Riding Hood»), «La Barbe bleue» («Blue Beard»), «Les Fées» («The Enchanted Ones», or «Diamonds and Toads»), «Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre» («Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper»), «Riquet à la Houppe» («Riquet with the Tuft»), and «Le Petit Poucet» («Hop o’ My Thumb»).[3] The book displayed a frontispiece depicting an old woman telling tales to a group of three children beneath a placard inscribed «CONTES DE MA MERE L’OYE» (Tales of Mother Goose).[4] The book was an instant success.[3]

Le Maître Chat first was translated into English as «The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots» by Robert Samber in 1729 and published in London for J. Pote and R. Montagu with its original companion tales in Histories, or Tales of Past Times, By M. Perrault.[note 1][16] The book was advertised in June 1729 as being «very entertaining and instructive for children».[16] A frontispiece similar to that of the first French edition appeared in the English edition launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4] Samber’s translation has been described as «faithful and straightforward, conveying attractively the concision, liveliness and gently ironic tone of Perrault’s prose, which itself emulated the direct approach of oral narrative in its elegant simplicity.»[17] Since that publication, the tale has been translated into various languages and published around the world.

[edit]

Perrault’s son Pierre Darmancour was assumed to have been responsible for the authorship of Histoires with the evidence cited being the book’s dedication to Élisabeth Charlotte d’Orléans, the youngest niece of Louis XIV, which was signed «P. Darmancour». Perrault senior, however, was known for some time to have been interested in contes de veille or contes de ma mère l’oye, and in 1693 published a versification of «Les Souhaits Ridicules» and, in 1694, a tale with a Cinderella theme called «Peau d’Ane».[4] Further, a handwritten and illustrated manuscript of five of the tales (including Le Maistre Chat ou le Chat Botté) existed two years before the tale’s 1697 Paris publication.[4]

Pierre Darmancour was sixteen or seventeen years old at the time the manuscript was prepared and, as scholars Iona and Peter Opie note, quite unlikely to have been interested in recording fairy tales.[4] Darmancour, who became a soldier, showed no literary inclinations, and, when he died in 1700, his obituary made no mention of any connection with the tales. However, when Perrault senior died in 1703, the newspaper alluded to his being responsible for «La Belle au bois dormant», which the paper had published in 1696.[4]

Analysis[edit]

In folkloristics, Puss in Boots is classified as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots», a subtype of ATU 545, «The Cat as Helper».[18] Folklorists Joseph Jacobs and Stith Thompson point that the Perrault’s tale is the possible source of the Cat Helper story in later European folkloric traditions.[19][20] The tale has also spread to the Americas, and is known in Asia (India, Indonesia and Philippines).[21]

Variations of the feline helper across cultures replace the cat with a jackal or fox.[22][23][24] For instance, the helpful animal is a monkey «in all Philippine variants» according to Damiana Eugenio.[25]

Greek scholar Marianthi Kaplanoglou states that the tale type ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots» (or, locally, «The Helpful Fox»), is an «example» of «widely known stories (…) in the repertoires of Greek refugees from Asia Minor».[26]

Adaptations[edit]

Perrault’s tale has been adapted to various media over the centuries. Ludwig Tieck published a dramatic satire based on the tale, called Der gestiefelte Kater,[27] and, in 1812, the Brothers Grimm inserted a version of the tale into their Kinder- und Hausmärchen.[28] In ballet, Puss appears in the third act of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty in a pas de caractère with The White Cat.[6]

The phrase «enough to make a cat laugh» dates from the mid-1800s and is associated with the tale of Puss in Boots.[29]

The Bibliothèque de Carabas[30] book series was published by David Nutt in London in the late 19th century, in which the front cover of each volume depicts Puss in Boots reading a book.

In film and television, Walt Disney produced an animated black and white silent short based on the tale in 1922.[31]

It was also adapted by Toei as anime feature film in 1969, It followed by two sequels. Hayao Miyazaki made manga series as a promotional tie-in for the film. The title character, Pero, named after Perrault, has since then become the mascot of Toei Animation, with his face appearing in the studio’s logo.

In the mid-1980s, Puss in Boots was televised as an episode of Faerie Tale Theatre with Ben Vereen and Gregory Hines in the cast.[32]

1987’s anime Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics features Puss in Boots, This version of Puss cheats his good-natured master out of money to buy his boots and his hat, hunts the king’s favorite thrush for introduced his master to the king.

Another version from the Cannon Movie Tales series features Christopher Walken as Puss, who in this adaptation is a cat who turns into a human when wearing the boots.

The TV show Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child features the story in a Hawaiian setting. The episode stars the voices of David Hyde Pierce as Puss in Boots, Dean Cain as Kuhio, Pat Morita as King Makahana, and Ming-Na Wen as Lani. In addition, the shapeshifting ogre is replaced with a shapeshifting giant (voiced by Keone Young).

Another adaptation of the character with little relation to the story was in the Pokémon anime episode «Like a Meowth to a Flame,» where a Meowth owned by the character Tyson wore boots, a hat, and a neckerchief.

DreamWorks Animation’s 2004 animated film Shrek 2 features a version of the character voiced by Antonio Banderas (and modeled after Banderas’ performance as Zorro). An assassin initially hired to kill Shrek, Puss becomes one of Shrek’s most loyal allies following his defeat. Banderas also voices Puss in the third and fourth films in the Shrek franchise, and in a 2011 spin-off animated feature Puss in Boots, which spawned a 2022 sequel Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. Puss also appears in the Netflix/DreamWorks series The Adventures of Puss in Boots where he is voiced by Eric Bauza.

[edit]

Jacques Barchilon and Henry Pettit note in their introduction to The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes that the main motif of «Puss in Boots» is the animal as helper and that the tale «carries atavistic memories of the familiar totem animal as the father protector of the tribe found everywhere by missionaries and anthropologists.» They also note that the title is original with Perrault as are the boots; no tale prior to Perrault’s features a cat wearing boots.[33]

Woodcut frontispiece copied from the 1697 Paris edition of Perrault’s tales and published in the English-speaking world.

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie observe that «the tale is unusual in that the hero little deserves his good fortune, that is if his poverty, his being a third child, and his unquestioning acceptance of the cat’s sinful instructions, are not nowadays looked upon as virtues.» The cat should be acclaimed the prince of ‘con’ artists, they declare, as few swindlers have been so successful before or since.[11]

The success of Histoires is attributed to seemingly contradictory and incompatible reasons. While the literary skill employed in the telling of the tales has been recognized universally, it appears the tales were set down in great part as the author heard them told. The evidence for that assessment lies first in the simplicity of the tales, then in the use of words that were, in Perrault’s era, considered populaire and du bas peuple, and finally, in the appearance of vestigial passages that now are superfluous to the plot, do not illuminate the narrative, and thus, are passages the Opies believe a literary artist would have rejected in the process of creating a work of art. One such vestigial passage is Puss’s boots; his insistence upon the footwear is explained nowhere in the tale, it is not developed, nor is it referred to after its first mention except in an aside.[34]

According to the Opies, Perrault’s great achievement was accepting fairy tales at «their own level.» He recounted them with neither impatience nor mockery, and without feeling that they needed any aggrandisement such as a frame story—although he must have felt it useful to end with a rhyming moralité. Perrault would be revered today as the father of folklore if he had taken the time to record where he obtained his tales, when, and under what circumstances.[34]

Bruno Bettelheim remarks that «the more simple and straightforward a good character in a fairy tale, the easier it is for a child to identify with it and to reject the bad other.» The child identifies with a good hero because the hero’s condition makes a positive appeal to him. If the character is a very good person, then the child is likely to want to be good too. Amoral tales, however, show no polarization or juxtaposition of good and bad persons because amoral tales such as «Puss in Boots» build character, not by offering choices between good and bad, but by giving the child hope that even the meekest can survive. Morality is of little concern in these tales, but rather, an assurance is provided that one can survive and succeed in life.[35]

Small children can do little on their own and may give up in disappointment and despair with their attempts. Fairy stories, however, give great dignity to the smallest achievements (such as befriending an animal or being befriended by an animal, as in «Puss in Boots») and that such ordinary events may lead to great things. Fairy stories encourage children to believe and trust that their small, real achievements are important although perhaps not recognized at the moment.[36]

In Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion Jack Zipes notes that Perrault «sought to portray ideal types to reinforce the standards of the civilizing process set by upper-class French society».[8] A composite portrait of Perrault’s heroines, for example, reveals the author’s idealized female of upper-class society is graceful, beautiful, polite, industrious, well groomed, reserved, patient, and even somewhat stupid because for Perrault, intelligence in womankind would be threatening. Therefore, Perrault’s composite heroine passively waits for «the right man» to come along, recognize her virtues, and make her his wife. He acts, she waits. If his seventeenth century heroines demonstrate any characteristics, it is submissiveness.[37]

A composite of Perrault’s male heroes, however, indicates the opposite of his heroines: his male characters are not particularly handsome, but they are active, brave, ambitious, and deft, and they use their wit, intelligence, and great civility to work their way up the social ladder and to achieve their goals. In this case of course, it is the cat who displays the characteristics and the man benefits from his trickery and skills. Unlike the tales dealing with submissive heroines waiting for marriage, the male-centered tales suggest social status and achievement are more important than marriage for men. The virtues of Perrault’s heroes reflect upon the bourgeoisie of the court of Louis XIV and upon the nature of Perrault, who was a successful civil servant in France during the seventeenth century.[8]

According to fairy and folk tale researcher and commentator Jack Zipes, Puss is «the epitome of the educated bourgeois secretary who serves his master with complete devotion and diligence.»[37] The cat has enough wit and manners to impress the king, the intelligence to defeat the ogre, and the skill to arrange a royal marriage for his low-born master. Puss’s career is capped by his elevation to grand seigneur[8] and the tale is followed by a double moral: «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie et savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess.»[8]

The renowned illustrator of Dickens’ novels and stories, George Cruikshank, was shocked that parents would allow their children to read «Puss in Boots» and declared: «As it stood the tale was a succession of successful falsehoods—a clever lesson in lying!—a system of imposture rewarded with the greatest worldly advantages.»

Another critic, Maria Tatar, notes that there is little to admire in Puss—he threatens, flatters, deceives, and steals in order to promote his master. She further observes that Puss has been viewed as a «linguistic virtuoso», a creature who has mastered the arts of persuasion and rhetoric to acquire power and wealth.[5]

«Puss in Boots» has successfully supplanted its antecedents by Straparola and Basile and the tale has altered the shapes of many older oral trickster cat tales where they still are found. The morals Perrault attached to the tales are either at odds with the narrative, or beside the point. The first moral tells the reader that hard work and ingenuity are preferable to inherited wealth, but the moral is belied by the poor miller’s son who neither works nor uses his wit to gain worldly advantage, but marries into it through trickery performed by the cat. The second moral stresses womankind’s vulnerability to external appearances: fine clothes and a pleasant visage are enough to win their hearts. In an aside, Tatar suggests that if the tale has any redeeming meaning, «it has something to do with inspiring respect for those domestic creatures that hunt mice and look out for their masters.»[38]

Briggs does assert that cats were a form of fairy in their own right having something akin to a fairy court and their own set of magical powers. Still, it is rare in Europe’s fairy tales for a cat to be so closely involved with human affairs. According to Jacob Grimm, Puss shares many of the features that a household fairy or deity would have including a desire for boots which could represent seven-league boots. This may mean that the story of «Puss and Boots» originally represented the tale of a family deity aiding an impoverished family member.[39][self-published source]

Stefan Zweig, in his 1939 novel, Ungeduld des Herzens, references Puss in Boots’ procession through a rich and varied countryside with his master and drives home his metaphor with a mention of Seven League Boots.

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ The distinction of being the first to translate the tales into English was long questioned. An edition styled Histories or Tales of Past Times, told by Mother Goose, with Morals. Written in French by M. Perrault, and Englished by G.M. Gent bore the publication date of 1719, thus casting doubt upon Samber being the first translator. In 1951, however, the date was proven to be a misprint for 1799 and Samber’s distinction as the first translator was assured.

- Footnotes

- ^ W. G. Waters, The Mysterious Giovan Francesco Straparola, in Jack Zipes, a c. di, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974 Further info: Little Red Pentecostal Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Peter J. Leithart, July 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Opie & Opie 1974, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Opie & Opie 1974, p. 23.

- ^ a b Tatar 2002, p. 234

- ^ a b Brown 2007, p. 351

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 113–116

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 1991, p. 26

- ^ Darnton, Robert (1984). The Great Cat Massacre. New York, NY: Basic Books, Ink. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-465-01274-9.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Opie & Opie 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 20.

- ^ Zipes 2001, p. 877

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 24.

- ^ Gillespie & Hopkins 2005, p. 351

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 58-59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s sons. 1916. pp. 239-240.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2006). «The Fox in World Literature: Reflections on a ‘Fictional Animal’«. Asian Folklore Studies. 65 (2): 133–160. JSTOR 30030396.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Eugenio, Damiana L. (1985). «Philippine Folktales: An Introduction». Asian Folklore Studies. 44 (2): 155–177. doi:10.2307/1178506. JSTOR 1178506.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (December 2010). «Two Storytellers from the Greek-Orthodox Communities of Ottoman Asia Minor. Analyzing Some Micro-data in Comparative Folklore». Fabula. 51 (3–4): 251–265. doi:10.1515/fabl.2010.024. S2CID 161511346.

- ^ Paulin 2002, p. 65

- ^ Wunderer 2008, p. 202

- ^ «https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/enough+to+make+a+cat+laugh»>enough to make a cat laugh

- ^ «Nutt, Alfred Trübner». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «Puss in Boots». The Disney Encyclopedia of Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ Zipes 1997, p. 102

- ^ Barchilon 1960, pp. 14, 16

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 22.

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 10

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 73

- ^ a b Zipes 1991, p. 25

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 235

- ^ Nukiuk H. 2011 Grimm’s Fairies: Discover the Fairies of Europe’s Fairy Tales, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Works cited

- Barchilon, Jacques (1960), The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes, Denver, CO: Alan Swallow

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1977) [1975, 1976], The Uses of Enchantment, New York: Random House: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-394-72265-5

- Brown, David (2007), Tchaikovsky, New York: Pegasus Books LLC, ISBN 978-1-933648-30-9

- Gillespie, Stuart; Hopkins, David, eds. (2005), The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English: 1660–1790, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924622-X

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Paulin, Roger (2002) [1985], Ludwig Tieck, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-815852-1

- Tatar, Maria (2002), The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- Wunderer, Rolf (2008), «Der gestiefelte Kater» als Unternehmer, Weisbaden: Gabler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8349-0772-1

- Zipes, Jack David (1991) [1988], Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-90513-3

- Zipes, Jack David (2001), The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- Zipes, Jack David (1997), Happily Ever After, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-91851-0

Further reading[edit]

- Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- Neuhaus, Mareike (2011). «The Rhetoric of Harry Robinson’s ‘Cat With the Boots On’«. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. 44 (2): 35–51. JSTOR 44029507. Project MUSE 440541 ProQuest 871355970.

- Nikolajeva, Maria (2009). «Devils, Demons, Familiars, Friends: Toward a Semiotics of Literary Cats». Marvels & Tales. 23 (2): 248–267. JSTOR 41388926.

- Blair, Graham (2019). «Jack Ships to the Cat». Clever Maids, Fearless Jacks, and a Cat: Fairy Tales from a Living Oral Tradition. University Press of Colorado. pp. 93–103. ISBN 978-1-60732-919-0. JSTOR j.ctvqc6hwd.11.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Origin of the Story of ‘Puss in Boots’

- «Puss in Boots» – English translation from The Blue Fairy Book (1889)

- «Puss in Boots» – Beautifully illustrated in The Colorful Story Book (1941)

Master Cat, or Puss in Boots, The public domain audiobook at LibriVox

| «Puss in Boots» | |

|---|---|

| by Giovanni Francesco Straparola Giambattista Basile Charles Perrault |

|

Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer |

|

| Country | Italy (1550–1553) France (1697) |

| Language | Italian (originally) |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

«Puss in Boots» (Italian: Il gatto con gli stivali) is an Italian[1][2] fairy tale, later spread throughout the rest of Europe, about an anthropomorphic cat who uses trickery and deceit to gain power, wealth, and the hand of a princess in marriage for his penniless and low-born master.

The oldest written telling is by Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola, who included it in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–1553) in XIV–XV. Another version was published in 1634 by Giambattista Basile with the title Cagliuso, and a tale was written in French at the close of the seventeenth century by Charles Perrault (1628–1703), a retired civil servant and member of the Académie française. There is a version written by Girolamo Morlini, from whom Straparola used various tales in The Facetious Nights of Straparola.[3] The tale appeared in a handwritten and illustrated manuscript two years before its 1697 publication by Barbin in a collection of eight fairy tales by Perrault called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[4][5] The book was an instant success and remains popular.[3]

Perrault’s Histoires has had considerable impact on world culture. The original Italian title of the first edition was Costantino Fortunato, but was later known as Il gatto con gli stivali (lit. The cat with the boots); the French title was «Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités» with the subtitle «Les Contes de ma mère l’Oye» («Stories or Fairy Tales from Past Times with Morals», subtitled «Mother Goose Tales»). The frontispiece to the earliest English editions depicts an old woman telling tales to a group of children beneath a placard inscribed «MOTHER GOOSE’S TALES» and is credited with launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4]

«Puss in Boots» has provided inspiration for composers, choreographers, and other artists over the centuries. The cat appears in the third act pas de caractère of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty,[6] appears in the sequels and self-titled Shrek movie to the animated film Shrek and is signified in the logo of Japanese anime studio Toei Animation. Puss in Boots is also a popular pantomime in the UK.

Plot[edit]

The tale opens with the third and youngest son of a miller receiving his inheritance — a cat. At first, the youngest son laments, as the eldest brother gains their father’s mill, and the middle brother gets the mule-and-cart. However, the feline is no ordinary cat, but one who requests and receives a pair of boots. Determined to make his master’s fortune, the cat bags a rabbit in the forest and presents it to the king as a gift from his master, the fictional Marquis of Carabas. The cat continues making gifts of game to the king for several months, for which he is rewarded.

Puss meets the ogre in a nineteenth-century illustration by Gustave Doré

One day, the king decides to take a drive with his daughter. The cat persuades his master to remove his clothes and enter the river which their carriage passes. The cat disposes of his master’s clothing beneath a rock. As the royal coach nears, the cat begins calling for help in great distress. When the king stops to investigate, the cat tells him that his master the Marquis has been bathing in the river and robbed of his clothing. The king has the young man brought from the river, dressed in a splendid suit of clothes, and seated in the coach with his daughter, who falls in love with him at once.

The cat hurries ahead of the coach, ordering the country folk along the road to tell the king that the land belongs to the «Marquis of Carabas», saying that if they do not he will cut them into mincemeat. The cat then happens upon a castle inhabited by an ogre who is capable of transforming himself into a number of creatures. The ogre displays his ability by changing into a lion, frightening the cat, who then tricks the ogre into changing into a mouse. The cat then pounces upon the mouse and devours it. The king arrives at the castle that formerly belonged to the ogre, and impressed with the bogus Marquis and his estate, gives the lad the princess in marriage. Thereafter; the cat enjoys life as a great lord who runs after mice only for his own amusement.[7]

The tale is followed immediately by two morals; «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie and savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess».[8] The Italian translation by Carlo Collodi notes that the tale gives useful advice if you happen to be a cat or a Marquis of Carabas.

This is the theme in France, but other versions of this theme exist in Asia, Africa, and South America.[9]

Background[edit]

Handwritten and illustrated manuscript of Perrault’s «Le Maître Chat» dated 1695

Perrault’s the «Master Cat or Puss in Boots» is the most renowned tale in all of Western folklore of the animal as helper.[10] However, the trickster cat did not originate with Perrault.[11] Centuries before the publication of Perrault’s tale, Somadeva, a Kashmir Brahmin, assembled a vast collection of Indian folk tales called Kathā Sarit Sāgara (lit. «The ocean of the streams of stories») that featured stock fairy tale characters and trappings such as invincible swords, vessels that replenish their contents, and helpful animals. In the Panchatantra (lit. «Five Principles»), a collection of Hindu tales from the second century BC., a tale follows a cat who fares much less well than Perrault’s Puss as he attempts to make his fortune in a king’s palace.[12]

In 1553, «Costantino Fortunato», a tale similar to «Le Maître Chat», was published in Venice in Giovanni Francesco Straparola’s Le Piacevoli Notti (lit. The Facetious Nights),[13] the first European storybook to include fairy tales.[14] In Straparola’s tale however, the poor young man is the son of a Bohemian woman, the cat is a fairy in disguise, the princess is named Elisetta, and the castle belongs not to an ogre but to a lord who conveniently perishes in an accident. The poor young man eventually becomes King of Bohemia.[13] An edition of Straparola was published in France in 1560.[10] The abundance of oral versions after Straparola’s tale may indicate an oral source to the tale; it also is possible Straparola invented the story.[15]

In 1634, another tale with a trickster cat as hero was published in Giambattista Basile’s collection Pentamerone although neither the collection nor the tale were published in France during Perrault’s lifetime. In Basile’s version, the lad is a beggar boy called Gagliuso (sometimes Cagliuso) whose fortunes are achieved in a manner similar to Perrault’s Puss. However, the tale ends with Cagliuso, in gratitude to the cat, promising the feline a gold coffin upon his death. Three days later, the cat decides to test Gagliuso by pretending to be dead and is mortified to hear Gagliuso tell his wife to take the dead cat by its paws and throw it out the window. The cat leaps up, demanding to know whether this was his promised reward for helping the beggar boy to a better life. The cat then rushes away, leaving his master to fend for himself.[13] In another rendition, the cat performs acts of bravery, then a fairy comes and turns him to his normal state to be with other cats.

It is likely that Perrault was aware of the Straparola tale, since ‘Facetious Nights’ was translated into French in the sixteenth century and subsequently passed into the oral tradition.[3]

Publication[edit]

The oldest record of written history was published in Venice by the Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–53) in XIV-XV. His original title was Costantino Fortunato (lit. Lucky Costantino).

The story was published under the French title Le Maître Chat, ou le Chat Botté (‘Master Cat, or the Booted Cat’) by Barbin in Paris in January 1697 in a collection of tales called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[3] The collection included «La Belle au bois dormant» («The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood»), «Le petit chaperon rouge» («Little Red Riding Hood»), «La Barbe bleue» («Blue Beard»), «Les Fées» («The Enchanted Ones», or «Diamonds and Toads»), «Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre» («Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper»), «Riquet à la Houppe» («Riquet with the Tuft»), and «Le Petit Poucet» («Hop o’ My Thumb»).[3] The book displayed a frontispiece depicting an old woman telling tales to a group of three children beneath a placard inscribed «CONTES DE MA MERE L’OYE» (Tales of Mother Goose).[4] The book was an instant success.[3]

Le Maître Chat first was translated into English as «The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots» by Robert Samber in 1729 and published in London for J. Pote and R. Montagu with its original companion tales in Histories, or Tales of Past Times, By M. Perrault.[note 1][16] The book was advertised in June 1729 as being «very entertaining and instructive for children».[16] A frontispiece similar to that of the first French edition appeared in the English edition launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4] Samber’s translation has been described as «faithful and straightforward, conveying attractively the concision, liveliness and gently ironic tone of Perrault’s prose, which itself emulated the direct approach of oral narrative in its elegant simplicity.»[17] Since that publication, the tale has been translated into various languages and published around the world.

[edit]

Perrault’s son Pierre Darmancour was assumed to have been responsible for the authorship of Histoires with the evidence cited being the book’s dedication to Élisabeth Charlotte d’Orléans, the youngest niece of Louis XIV, which was signed «P. Darmancour». Perrault senior, however, was known for some time to have been interested in contes de veille or contes de ma mère l’oye, and in 1693 published a versification of «Les Souhaits Ridicules» and, in 1694, a tale with a Cinderella theme called «Peau d’Ane».[4] Further, a handwritten and illustrated manuscript of five of the tales (including Le Maistre Chat ou le Chat Botté) existed two years before the tale’s 1697 Paris publication.[4]

Pierre Darmancour was sixteen or seventeen years old at the time the manuscript was prepared and, as scholars Iona and Peter Opie note, quite unlikely to have been interested in recording fairy tales.[4] Darmancour, who became a soldier, showed no literary inclinations, and, when he died in 1700, his obituary made no mention of any connection with the tales. However, when Perrault senior died in 1703, the newspaper alluded to his being responsible for «La Belle au bois dormant», which the paper had published in 1696.[4]

Analysis[edit]

In folkloristics, Puss in Boots is classified as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots», a subtype of ATU 545, «The Cat as Helper».[18] Folklorists Joseph Jacobs and Stith Thompson point that the Perrault’s tale is the possible source of the Cat Helper story in later European folkloric traditions.[19][20] The tale has also spread to the Americas, and is known in Asia (India, Indonesia and Philippines).[21]

Variations of the feline helper across cultures replace the cat with a jackal or fox.[22][23][24] For instance, the helpful animal is a monkey «in all Philippine variants» according to Damiana Eugenio.[25]

Greek scholar Marianthi Kaplanoglou states that the tale type ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots» (or, locally, «The Helpful Fox»), is an «example» of «widely known stories (…) in the repertoires of Greek refugees from Asia Minor».[26]

Adaptations[edit]

Perrault’s tale has been adapted to various media over the centuries. Ludwig Tieck published a dramatic satire based on the tale, called Der gestiefelte Kater,[27] and, in 1812, the Brothers Grimm inserted a version of the tale into their Kinder- und Hausmärchen.[28] In ballet, Puss appears in the third act of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty in a pas de caractère with The White Cat.[6]

The phrase «enough to make a cat laugh» dates from the mid-1800s and is associated with the tale of Puss in Boots.[29]

The Bibliothèque de Carabas[30] book series was published by David Nutt in London in the late 19th century, in which the front cover of each volume depicts Puss in Boots reading a book.

In film and television, Walt Disney produced an animated black and white silent short based on the tale in 1922.[31]

It was also adapted by Toei as anime feature film in 1969, It followed by two sequels. Hayao Miyazaki made manga series as a promotional tie-in for the film. The title character, Pero, named after Perrault, has since then become the mascot of Toei Animation, with his face appearing in the studio’s logo.

In the mid-1980s, Puss in Boots was televised as an episode of Faerie Tale Theatre with Ben Vereen and Gregory Hines in the cast.[32]

1987’s anime Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics features Puss in Boots, This version of Puss cheats his good-natured master out of money to buy his boots and his hat, hunts the king’s favorite thrush for introduced his master to the king.

Another version from the Cannon Movie Tales series features Christopher Walken as Puss, who in this adaptation is a cat who turns into a human when wearing the boots.

The TV show Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child features the story in a Hawaiian setting. The episode stars the voices of David Hyde Pierce as Puss in Boots, Dean Cain as Kuhio, Pat Morita as King Makahana, and Ming-Na Wen as Lani. In addition, the shapeshifting ogre is replaced with a shapeshifting giant (voiced by Keone Young).

Another adaptation of the character with little relation to the story was in the Pokémon anime episode «Like a Meowth to a Flame,» where a Meowth owned by the character Tyson wore boots, a hat, and a neckerchief.

DreamWorks Animation’s 2004 animated film Shrek 2 features a version of the character voiced by Antonio Banderas (and modeled after Banderas’ performance as Zorro). An assassin initially hired to kill Shrek, Puss becomes one of Shrek’s most loyal allies following his defeat. Banderas also voices Puss in the third and fourth films in the Shrek franchise, and in a 2011 spin-off animated feature Puss in Boots, which spawned a 2022 sequel Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. Puss also appears in the Netflix/DreamWorks series The Adventures of Puss in Boots where he is voiced by Eric Bauza.

[edit]

Jacques Barchilon and Henry Pettit note in their introduction to The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes that the main motif of «Puss in Boots» is the animal as helper and that the tale «carries atavistic memories of the familiar totem animal as the father protector of the tribe found everywhere by missionaries and anthropologists.» They also note that the title is original with Perrault as are the boots; no tale prior to Perrault’s features a cat wearing boots.[33]

Woodcut frontispiece copied from the 1697 Paris edition of Perrault’s tales and published in the English-speaking world.

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie observe that «the tale is unusual in that the hero little deserves his good fortune, that is if his poverty, his being a third child, and his unquestioning acceptance of the cat’s sinful instructions, are not nowadays looked upon as virtues.» The cat should be acclaimed the prince of ‘con’ artists, they declare, as few swindlers have been so successful before or since.[11]

The success of Histoires is attributed to seemingly contradictory and incompatible reasons. While the literary skill employed in the telling of the tales has been recognized universally, it appears the tales were set down in great part as the author heard them told. The evidence for that assessment lies first in the simplicity of the tales, then in the use of words that were, in Perrault’s era, considered populaire and du bas peuple, and finally, in the appearance of vestigial passages that now are superfluous to the plot, do not illuminate the narrative, and thus, are passages the Opies believe a literary artist would have rejected in the process of creating a work of art. One such vestigial passage is Puss’s boots; his insistence upon the footwear is explained nowhere in the tale, it is not developed, nor is it referred to after its first mention except in an aside.[34]

According to the Opies, Perrault’s great achievement was accepting fairy tales at «their own level.» He recounted them with neither impatience nor mockery, and without feeling that they needed any aggrandisement such as a frame story—although he must have felt it useful to end with a rhyming moralité. Perrault would be revered today as the father of folklore if he had taken the time to record where he obtained his tales, when, and under what circumstances.[34]

Bruno Bettelheim remarks that «the more simple and straightforward a good character in a fairy tale, the easier it is for a child to identify with it and to reject the bad other.» The child identifies with a good hero because the hero’s condition makes a positive appeal to him. If the character is a very good person, then the child is likely to want to be good too. Amoral tales, however, show no polarization or juxtaposition of good and bad persons because amoral tales such as «Puss in Boots» build character, not by offering choices between good and bad, but by giving the child hope that even the meekest can survive. Morality is of little concern in these tales, but rather, an assurance is provided that one can survive and succeed in life.[35]

Small children can do little on their own and may give up in disappointment and despair with their attempts. Fairy stories, however, give great dignity to the smallest achievements (such as befriending an animal or being befriended by an animal, as in «Puss in Boots») and that such ordinary events may lead to great things. Fairy stories encourage children to believe and trust that their small, real achievements are important although perhaps not recognized at the moment.[36]

In Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion Jack Zipes notes that Perrault «sought to portray ideal types to reinforce the standards of the civilizing process set by upper-class French society».[8] A composite portrait of Perrault’s heroines, for example, reveals the author’s idealized female of upper-class society is graceful, beautiful, polite, industrious, well groomed, reserved, patient, and even somewhat stupid because for Perrault, intelligence in womankind would be threatening. Therefore, Perrault’s composite heroine passively waits for «the right man» to come along, recognize her virtues, and make her his wife. He acts, she waits. If his seventeenth century heroines demonstrate any characteristics, it is submissiveness.[37]

A composite of Perrault’s male heroes, however, indicates the opposite of his heroines: his male characters are not particularly handsome, but they are active, brave, ambitious, and deft, and they use their wit, intelligence, and great civility to work their way up the social ladder and to achieve their goals. In this case of course, it is the cat who displays the characteristics and the man benefits from his trickery and skills. Unlike the tales dealing with submissive heroines waiting for marriage, the male-centered tales suggest social status and achievement are more important than marriage for men. The virtues of Perrault’s heroes reflect upon the bourgeoisie of the court of Louis XIV and upon the nature of Perrault, who was a successful civil servant in France during the seventeenth century.[8]

According to fairy and folk tale researcher and commentator Jack Zipes, Puss is «the epitome of the educated bourgeois secretary who serves his master with complete devotion and diligence.»[37] The cat has enough wit and manners to impress the king, the intelligence to defeat the ogre, and the skill to arrange a royal marriage for his low-born master. Puss’s career is capped by his elevation to grand seigneur[8] and the tale is followed by a double moral: «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie et savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess.»[8]

The renowned illustrator of Dickens’ novels and stories, George Cruikshank, was shocked that parents would allow their children to read «Puss in Boots» and declared: «As it stood the tale was a succession of successful falsehoods—a clever lesson in lying!—a system of imposture rewarded with the greatest worldly advantages.»

Another critic, Maria Tatar, notes that there is little to admire in Puss—he threatens, flatters, deceives, and steals in order to promote his master. She further observes that Puss has been viewed as a «linguistic virtuoso», a creature who has mastered the arts of persuasion and rhetoric to acquire power and wealth.[5]

«Puss in Boots» has successfully supplanted its antecedents by Straparola and Basile and the tale has altered the shapes of many older oral trickster cat tales where they still are found. The morals Perrault attached to the tales are either at odds with the narrative, or beside the point. The first moral tells the reader that hard work and ingenuity are preferable to inherited wealth, but the moral is belied by the poor miller’s son who neither works nor uses his wit to gain worldly advantage, but marries into it through trickery performed by the cat. The second moral stresses womankind’s vulnerability to external appearances: fine clothes and a pleasant visage are enough to win their hearts. In an aside, Tatar suggests that if the tale has any redeeming meaning, «it has something to do with inspiring respect for those domestic creatures that hunt mice and look out for their masters.»[38]

Briggs does assert that cats were a form of fairy in their own right having something akin to a fairy court and their own set of magical powers. Still, it is rare in Europe’s fairy tales for a cat to be so closely involved with human affairs. According to Jacob Grimm, Puss shares many of the features that a household fairy or deity would have including a desire for boots which could represent seven-league boots. This may mean that the story of «Puss and Boots» originally represented the tale of a family deity aiding an impoverished family member.[39][self-published source]

Stefan Zweig, in his 1939 novel, Ungeduld des Herzens, references Puss in Boots’ procession through a rich and varied countryside with his master and drives home his metaphor with a mention of Seven League Boots.

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ The distinction of being the first to translate the tales into English was long questioned. An edition styled Histories or Tales of Past Times, told by Mother Goose, with Morals. Written in French by M. Perrault, and Englished by G.M. Gent bore the publication date of 1719, thus casting doubt upon Samber being the first translator. In 1951, however, the date was proven to be a misprint for 1799 and Samber’s distinction as the first translator was assured.

- Footnotes

- ^ W. G. Waters, The Mysterious Giovan Francesco Straparola, in Jack Zipes, a c. di, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974 Further info: Little Red Pentecostal Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Peter J. Leithart, July 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Opie & Opie 1974, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Opie & Opie 1974, p. 23.

- ^ a b Tatar 2002, p. 234

- ^ a b Brown 2007, p. 351

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 113–116

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 1991, p. 26

- ^ Darnton, Robert (1984). The Great Cat Massacre. New York, NY: Basic Books, Ink. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-465-01274-9.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Opie & Opie 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 20.

- ^ Zipes 2001, p. 877

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 24.

- ^ Gillespie & Hopkins 2005, p. 351

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 58-59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s sons. 1916. pp. 239-240.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2006). «The Fox in World Literature: Reflections on a ‘Fictional Animal’«. Asian Folklore Studies. 65 (2): 133–160. JSTOR 30030396.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Eugenio, Damiana L. (1985). «Philippine Folktales: An Introduction». Asian Folklore Studies. 44 (2): 155–177. doi:10.2307/1178506. JSTOR 1178506.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (December 2010). «Two Storytellers from the Greek-Orthodox Communities of Ottoman Asia Minor. Analyzing Some Micro-data in Comparative Folklore». Fabula. 51 (3–4): 251–265. doi:10.1515/fabl.2010.024. S2CID 161511346.

- ^ Paulin 2002, p. 65

- ^ Wunderer 2008, p. 202

- ^ «https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/enough+to+make+a+cat+laugh»>enough to make a cat laugh

- ^ «Nutt, Alfred Trübner». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «Puss in Boots». The Disney Encyclopedia of Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ Zipes 1997, p. 102

- ^ Barchilon 1960, pp. 14, 16

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 22.

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 10

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 73

- ^ a b Zipes 1991, p. 25

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 235

- ^ Nukiuk H. 2011 Grimm’s Fairies: Discover the Fairies of Europe’s Fairy Tales, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Works cited

- Barchilon, Jacques (1960), The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes, Denver, CO: Alan Swallow

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1977) [1975, 1976], The Uses of Enchantment, New York: Random House: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-394-72265-5

- Brown, David (2007), Tchaikovsky, New York: Pegasus Books LLC, ISBN 978-1-933648-30-9

- Gillespie, Stuart; Hopkins, David, eds. (2005), The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English: 1660–1790, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924622-X

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Paulin, Roger (2002) [1985], Ludwig Tieck, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-815852-1

- Tatar, Maria (2002), The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- Wunderer, Rolf (2008), «Der gestiefelte Kater» als Unternehmer, Weisbaden: Gabler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8349-0772-1

- Zipes, Jack David (1991) [1988], Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-90513-3

- Zipes, Jack David (2001), The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- Zipes, Jack David (1997), Happily Ever After, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-91851-0

Further reading[edit]

- Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- Neuhaus, Mareike (2011). «The Rhetoric of Harry Robinson’s ‘Cat With the Boots On’«. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. 44 (2): 35–51. JSTOR 44029507. Project MUSE 440541 ProQuest 871355970.

- Nikolajeva, Maria (2009). «Devils, Demons, Familiars, Friends: Toward a Semiotics of Literary Cats». Marvels & Tales. 23 (2): 248–267. JSTOR 41388926.

- Blair, Graham (2019). «Jack Ships to the Cat». Clever Maids, Fearless Jacks, and a Cat: Fairy Tales from a Living Oral Tradition. University Press of Colorado. pp. 93–103. ISBN 978-1-60732-919-0. JSTOR j.ctvqc6hwd.11.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Origin of the Story of ‘Puss in Boots’

- «Puss in Boots» – English translation from The Blue Fairy Book (1889)

- «Puss in Boots» – Beautifully illustrated in The Colorful Story Book (1941)

Master Cat, or Puss in Boots, The public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Литературное чтение, 2 класс

Урок 64. Ш. Перро «Кот в сапогах»

Перечень вопросов, рассматриваемых на уроке:

- Шарль Перро и его сказки

- Особенности жанра волшебной сказки

- Литературная (авторская) сказка

Тезаурус

Место сказки «Кот в сапогах» в творчестве Шарля Перро; особенности жанра волшебной сказки; литературная (авторская) сказка.

Сказка — это занимательный рассказ о необыкновенных событиях и приключениях.

Литературная (авторская) сказка — ориентированное на вымысел произведение, тесно связанное с народной сказкой, но, в отличие от нее, принадлежащее конкретному автору.

Волшебная сказка — это повествование о необыкновенных событиях и приключениях, в которых участвуют нереальные персонажи.

Общие особенности волшебных сказок: наличие очевидной фантастики, волшебства, чуда (волшебные персонажи и предметы).

Ключевые слова

Творчество, писатель-сказочник, Шарль Перро, волшебная сказка, литературная сказка.

Список литературы

1. Литературное чтение. 2 класс. Учеб. для общеобразоват. организаций. В 2 ч. / Л.Ф. Климанова, В.Г. Горецкий, М.В. Голованова и др. – 9-е изд. – М.: Просвещение, 2018. – С. 182–193.

2. Литературное чтение. 2 класс. В 2 ч. Аудиоприложение к учебнику Л.Ф. Климановой, В.Г. Горецкого, М.В. Головановой и др. – М.: Просвещение, 2013.

3. Литературное чтение. Методические рекомендации. 2 класс / Н.А. Стефаненко. – М.: Просвещение, 2018.

Обозначение ожидаемых результатов.

На уроке узнаем о творчестве Ш. Перро, особенностях волшебной сказки, о том, какие сказки считают литературными; вспомним ход сказки «Кот в сапогах».

Основное содержание урока

Сегодня у нас необычный урок: мы отправимся в сказочный мир Шарля Перро и героев его сказок. Что вы знаете об этом человеке? Почему он запомнился многим поколениям читателей как писатель-сказочник? Потому что он писал сказки. Какие сказки Шарля Перро вам известны? «Золушка», «Мальчик-с-пальчик», «Красная Шапочка», «Ослиная шкура».

Шарль Перро, известный сейчас всем взрослым и детям как автор «Красной Шапочки», «Кота в сапогах», «Золушки» и других сказок, родился в городе Турне 12 января 1628 года. Говорят, что при рождении младенец закричал так, что было слышно на другом конце квартала, возвестив весь мир о своем появлении на свет.

Вырос Шарль Перро в обеспеченной богатой образованной семье. Семья была многодетной. Все братья Пьеро, в том числе и Шарль, закончили колледж Бове. Шарль Перро поступил в этот колледж в 8 лет и окончил в нем факультет искусств. Известно, что сначала Шарль Перро отнюдь не блистал успехами в обучении, но потом всё резко изменилось. Он выдвинулся в число лучших учеников и вместе с другом разработал свою систему занятий — такую, что даже перегнал программу по истории, латыни и французскому языку.

Шарль Перро усердно делал карьеру, и о литературе как серьезном занятии даже и не думал. Он стал богат, силен, влиятелен.

Сказки Шарля Перро были написаны как сказки «нравственные» и обучающие жизни. Известен факт, что основу всех сюжетов сказок Шарля Перро составляют известные народные сказки, а не его авторский замысел. Перро же создал на их основе авторскую литературную сказку.

Дома вы прочитали сказку Шарля Перро «Кот в сапогах».

Если её написал автор, то какая это сказка? (Литературная (авторская).)

Можно ли сказку «Кот в сапогах» отнести к жанру волшебных сказок?

Без чего не может существовать волшебная сказка?

Давайте проследим, какое волшебство есть в сказке «Кот в сапогах».

Сапоги. Превращение Людоеда в льва. Превращение Людоеда в мышь.

А теперь обратимся к самой сказке. Ответьте на некоторые вопросы, подтверждая свои ответы цитатами из текста.

Назовите главных героев сказки?

Какое наследство оставил сыновьям отец?

Почему именно младшему брату достался кот?

Почему именно младшему брату достался кот?

Почему он горевал по поводу своего наследства?

Как отреагировал кот на то, что из его шкуры сошьют рукавицы?

Почему кот решил помочь хозяину?

Почему хозяин поверил коту?

Куда отправился кот с добычей?

Какое новое имя кот дал своему хозяину?

Какую хитрость придумал кот, чтобы представить своего хозяина королю?

Почему король помог Маркизу?

О какой волшебной силе Людоеда разузнал кот?

Какое предложение сделал король Маркизу?

Почему кот перестал охотиться на мышей?

А вам известно, что изначально сказки Шарля Перро существовали в стихотворной форме?

Послушайте мораль к сказке «Кот в сапогах»:

И если мельников сынишка может

Принцессы сердце потревожить,

И смотрит на него она едва жива,

То значит молодость и радость

И без наследства будут в сладость,

И сердце любит, и кружится голова.

Значит, ни жизнь, ни сказка невозможны без любви! Будет любовь — будет и молодость, и радость даже без наследства! Вот такой интересный завет от Шарля Перро.

Разбор типового тренировочного задания

Текст вопроса: Ответьте на вопросы по содержанию сказки:

1. Животное, в которое Людоед превратился в первый раз.

2. Часть наследства, которое досталось старшему брату.

3. Часть наследства, которая досталась среднему брату.

4. Животное, в которое Людоед превратился во второй раз.

5. Какое имя придумал своему хозяину кот в сапогах?

6. Кто первым попался в мешок коту?

7. Кто сказал королю, что поля принадлежат маркизу Карабасу?

Карточки для подстановки:

1. Лев

2. Мельница

3. Осёл

4. Мышь

5. Маркиз де Карабас

6. Кролик

7. Жнецы

Ответ:

- Животное, в которое Людоед превратился в первый раз. (Лев)

2. Часть наследства, которое досталось старшему брату. (Мельница)

3. Часть наследства, которая досталась среднему брату. (Осёл)

4. Животное, в которое Людоед превратился во второй раз. (Мышь)

5. Какое имя придумал своему хозяину кот в сапогах? (Маркиз де Карабас)

6. Кто первым попался в мешок коту? (Кролик)

7. Кто сказал королю, что поля принадлежат маркизу Карабасу? (Жнецы)

8. Каких птиц преподнёс в дар королю кот? (Куропатки)

Разбор типового контрольного задания

Текст вопроса: Отгадайте произведение. Подчеркните слова-помощники

Принцесса быстро схватила веретено и не успела прикоснуться к нему, как предсказание феи исполнилось: она уколола палец и упала замертво….

Трудно описать словами, как хороша была спящая принцесса. Она нисколько не побледнела. Щеки у нее были розовые, а губы красные, точно кораллы.

Король приказал не тревожить принцессу до тех пор, пока не наступит час ее пробуждения.

Ответ:

Принцесса быстро схватила веретено и не успела прикоснуться к нему, как предсказание феи исполнилось: она уколола палец и упала ….

Трудно описать словами, как хороша была спящая принцесса. Она нисколько не побледнела. Щеки у нее были розовые, а губы красные, точно кораллы.

Король приказал не тревожить принцессу до тех пор, пока не наступит час ее пробуждения.

Ш.

Перро «Кот в сапогах»

Задачи: 1) в ходе

организованной познавательной деятельности уточнить содержание и

последовательность событий в сказке; 2) на основе анализа полученной информации

решать задачи на осмысление сюжета и главной мысли сказки; 3) в ходе

совместного обсуждения осознавать роль дружбы, взаимовыручки при преодолении

неблагоприятных жизненных ситуаций.

Ход

урока:

1.

Организационный момент.

-Нам

веселый дан звонок, начинается урок. Ребята, мы проводим урок литературного

чтения. Проверьте порядок на своих рабочих местах. Давайте улыбнемся друг другу

и пожелаем удачной работы.

2.

Актуализация знаний.

—

Что за зверь гуляет в сказке?

Усы

топорщит, щурит глазки,

В

шляпе, с саблею в руках,

И

в огромных сапогах. (Кот в сапогах)

-Ребята,

скажите, героем какой сказки является этот кот (Приложение 1)?

Покажите на выставке книг (Приложение

2) эту сказку Шарля Перро. Что помогло вам

правильно справиться с заданием? (название книги, автор, иллюстрация).

3.

Проверка домашнего задания.

-Дома

вы перечитывали сказку и сделали словарики для своих одноклассников, где

объяснили смысл, значение непонятных слов, встречающиеся в тексте. Кто готов

показать словарики? (Дети показывают рисунки в своих словариках, зачитывают

лексическое значение слов. Одноклассники оценивают работу по критериям:

понятность, красочность/эстетичность.)

4.

Мотивация познавательной деятельности.

-На

ваших партах лежат такие таблицы:

|

Знаю |

Хочу |

Узнал |

|

|

1. |

|||

|

2. |

|||

|

3.Содержание |

|||

|

4.Вид |

|||

|

5. |

|||

|

6.Понимание |

|||

|

7. |

-Отметьте знаком «+» в столбике «знаю» то, что вы хорошо знаете.

Давайте вместе посмотрим, что мы знаем, а чему нам предстоит научиться сегодня

на уроке. (У учителя на откидной доске такая же таблица, на которой он

работает: если большинство детей поставили «+» в своих

таблицах, то тогда и в общей таблице учитель ставит этот знак. Дети знают

автора и содержание произведения, героев сказки).