Как написать слово «будапештский» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «будапештский»?

будапе́штский

Правильное написание — будапештский, ударение падает на букву: е, безударными гласными являются: у, а, и.

Выделим согласные буквы — будапештский, к согласным относятся: б, д, п, ш, т, с, к, й, звонкие согласные: б, д, й, глухие согласные: п, ш, т, с, к.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 12,

- слогов — 4,

- гласных — 4,

- согласных — 8.

Формы слова: будапе́штский (от Будапе́шт).

Что означает имя Будапешт? Что обозначает имя Будапешт? Что значит имя Будапешт для человека? Какое значение имени Будапешт, происхождение, судьба и характер носителя? Какой национальности имя Будапешт? Как переводится имя Будапешт? Как правильно пишется имя Будапешт? Совместимость c именем Будапешт — подходящий цвет, камни обереги, планета покровитель и знак зодиака. Полная характеристика имени Будапешт и его подробный анализ вы можете прочитать онлайн в этой статье совершенно бесплатно.

Анализ имени Будапешт

Имя Будапешт состоит из 8 букв. Восемь букв в имени означают, что это кто угодно, только не прирожденный «человек семьи». Такие люди постоянно испытывают чувство неудовлетворенности существующим положением вещей, они всегда в процессе поиска чего-то нового, яркого, способного вызвать восхищение. Сами же они – воплощенное очарование, в самом прямом смысле слова: способны околдовать, увлечь, лишить разума. Проанализировав значение каждой буквы в имени Будапешт можно понять его тайный смысл и скрытое значение.

Значение имени Будапешт в нумерологии

Нумерология имени Будапешт может подсказать не только главные качества и характер человека. Но и определить его судьбу, показать успех в личной жизни, дать сведения о карьере, расшифровать судьбоносные знаки и даже предсказать будущее. Число имени Будапешт в нумерологии — 8. Девиз имени Будапешт и восьмерок по жизни: «Я лучше всех!»

- Планета-покровитель для имени Будапешт — Сатурн.

- Знак зодиака для имени Будапешт — Лев, Скорпион и Рыбы.

- Камни-талисманы для имени Будапешт — кальцит, киноварь, коралл, диоптаза, слоновая кость, черный лигнит, марказит, мика, опал, селенит, серпентин, дымчатый кварц.

«Восьмерка» в качестве одного из чисел нумерологического ядра – это показатель доминанантного начала, практицизма, материализма и неистребимой уверенности в собственных силах.

«Восьмерка» в числах имени Будапешт – Числе Выражения, Числе Души и Числе внешнего облика – это, прежде всего, способность уверенно обращаться с деньгами и обеспечивать себе стабильное материальное положение.

Лидеры по натуре, восьмерки невероятно трудолюбивы и выносливы. Природные организаторские способности, целеустремленность и незаурядный ум позволяют им достигать поставленных целей.

Человек Восьмерки напоминает сейф, так сложно его понять и расшифровать. Истинные мотивы и желания Восьмерки с именем Будапешт всегда скрыты от других, трудно найти точки соприкосновения и установить легкие отношения. Восьмерка хорошо разбирается в людях, чувствует характер, распознает слабости и сильные стороны окружающих. Любит контролировать и доминировать в общении, сама не признает своих ошибок. Очень часто жертвует своими интересами во имя семьи. Восьмерка азартна, любит нестандартные решения. В любой профессии добивается высокого уровня мастерства. Это хороший стратег, который не боится ответственности, но Восьмерке трудно быть на втором плане. Будапешт учится быстро, любит историю, искусство. Умеет хранить чужие секреты, по натуре прирожденный психолог. Порадовать Восьмерку можно лишь доверием и открытым общением.

- Влияние имени Будапешт на профессию и карьеру. Оптимальные варианты профессиональной самореализации «восьмерки – собственный бизнес, руководящая должность или политика. Окончательный выбор часто зависит от исходных предпосылок. Например, от того, кто папа – сенатор или владелец ателье мод — зависит, что значит число 8 в выборе конкретного занятия в жизни. Подходящие профессии: финансист, управленец, политик.

- Влияние имени Будапешт на личную жизнь. Число 8 в нумерологии отношений превращает совместную жизнь или брак в такое же коммерческое предприятие, как и любое другое. И речь в данном случае идет не о «браке по расчету» в общепринятом понимании этого выражения. Восьмерки обладают волевым характером, огромной энергией и авторитетом. Однажды разочаровавшись в человеке, они будут предъявлять огромные требования к следующим партнерам. Поэтому им важны те, кто просто придет им на помощь без лишних слов. Им подойдут единицы, двойки и восьмерки.

Планета покровитель имени Будапешт

Число 8 для имени Будапешт означает планету Сатурн. Люди этого типа одиноки, они часто сталкиваются с непониманием со стороны окружающих. Внешне обладатели имени Будапешт холодны, но это лишь маска, чтобы скрыть свою природную тягу к теплу и благополучию. Люди Сатурна не любят ничего поверхностного и не принимают опрометчивых решений. Они склонны к стабильности, к устойчивому материальному положению. Но всего этого им хоть и удается достичь, но только своим потом и кровью, ничего не дается им легко. Они постоянны во всем: в связях, в привычках, в работе. К старости носители имени Будапешт чаще всего материально обеспечены. Помимо всего прочего, упрямы, что способствует достижению каких-либо целей. Эти люди пунктуальны, расчетливы в хорошем смысле этого слова, осторожны, методичны, трудолюбивы. Как правило, люди Сатурна подчиняют себе, а не подчиняются сами. Они всегда верны и постоянны, на них можно положиться. Гармония достигается с людьми второго типа.

Знаки зодиака имени Будапешт

Для имени Будапешт подходят следующие знаки зодиака:

Цвет имени Будапешт

Розовый цвет имени Будапешт. Люди с именем, носящие розовый цвет, — сдержанные и хорошие слушатели, они никогда не спорят. Хотя всегда имеют своё мнение, которому строго следуют. От носителей имени Будапешт невозможно услышать критики в адрес других. А вот себя они оценивают люди с именем Будапешт всегда критично, из-за чего бывают частые душевные стяжания и депрессивные состояния. Они прекрасные семьянины, ведь их невозможно не любить. Положительные черты характера имени Будапешт – человеколюбие и душевность. Отрицательные черты характера имени Будапешт – депрессивность и критичность.

Как правильно пишется имя Будапешт

В русском языке грамотным написанием этого имени является — Будапешт. В английском языке имя Будапешт может иметь следующий вариант написания — Budapesht.

Склонение имени Будапешт по падежам

| Падеж | Вопрос | Имя |

| Именительный | Кто? | Будапешт |

| Родительный | Нет Кого? | Будапешт |

| Дательный | Рад Кому? | Будапешт |

| Винительный | Вижу Кого? | Будапешт |

| Творительный | Доволен Кем? | Будапешт |

| Предложный | Думаю О ком? | Будапешт |

Видео значение имени Будапешт

Вы согласны с описанием и значением имени Будапешт? Какую судьбу, характер и национальность имеют ваши знакомые с именем Будапешт? Каких известных и успешных людей с именем Будапешт вы еще знаете? Будем рады обсудить имя Будапешт более подробно с посетителями нашего сайта в комментариях ниже.

Если вы нашли ошибку в описании имени, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

×òî òàêîå «ÁÓÄÀÏÅØÒ»? Êàê ïðàâèëüíî ïèøåòñÿ äàííîå ñëîâî. Ïîíÿòèå è òðàêòîâêà.

ÁÓÄÀÏÅØÒ Áóäàïåøò

(Budapest), ñòîëèöà Âåíãðèè. Áóäàïåøò îáðàçîâàëñÿ ïóò¸ì îáúåäèíåíèÿ (1873) òðåõ ãîðîäîâ — Áóäû è Îáóäû íà âûñîêîì õîëìèñòîì ïðàâîì áåðåãó Äóíàÿ è Ïåøòà íà íèçêîì ëåâîì áåðåãó (âïåðâûå óïîìèíàþòñÿ â 1148). Ðàñïîëîæåííûé â æèâîïèñíîé äîëèíå, Áóäàïåøò ÿâëÿåòñÿ îäíèì èç êðàñèâåéøèõ ãîðîäîâ Åâðîïû. Óçêèå êðèâûå óëî÷êè ñðåäíåâåêîâîé Áóäû, óòîïàþùåé â ñàäàõ è îêðóæ¸ííîé öåïüþ ëåñèñòûõ ãîð, êîíòðàñòèðóþò ñî ñâîáîäíî ðàñêèíóâøèìèñÿ êâàðòàëàìè Ïåøòà, øèðîêèå ðàäèàëüíûå ìàãèñòðàëè êîòîðîãî ïåðåñåêàþò òðè ïîëóêîëüöà óëèö. Íàä ãîðîäîì ãîñïîäñòâóåò ãîðà Ãåëëåðò (íà ïðàâîì áåðåãó), ïîêðûòàÿ ñàäàìè è ïàðêàìè è óâåí÷àííàÿ ïàìÿòíèêîì Îñâîáîæäåíèÿ (áðîíçà, ãðàíèò, 1947, ñêóëüïòîð Æ. Êèøôàëóäè-Øòðîáëü). Ñðåäíåâåêîâûå ïîñòðîéêè Áóäàïåøòà (XI-XVI ââ.) ïî÷òè ïîëíîñòüþ óíè÷òîæåíû ìîíãîëî-òàòàðñêèì è òóðåöêèì íàøåñòâèÿìè 1241-42 è 1541. Ñîâðåìåííûé îáëèê ãîðîäà îïðåäåëÿþò ãëàâíûì îáðàçîì ïàðàäíûå ïîñòðîéêè êîíöà XIX-XX ââ.  ðàéîíå Îáóäà: îñòàòêè äðåâíåðèìñêîãî ïîñåëåíèÿ Àêâèíêóì (I-IV ââ., â òîì ÷èñëå äâà àìôèòåàòðà, õðàìû, òåðìû, òàê íàçûâàåìàÿ âèëëà Ãåðêóëåñà ñ ìîçàè÷íûì ïîëîì, ðàííåõðèñòèàíñêèå áàçèëèêè). Íà õîëìå â ðàéîíå Áóäà: îñòàòêè çàìêà (XIII — íà÷àëî XX ââ.) ñ êîðîëåâñêèì äâîðöîì (íûíå Ìóçåé çàìêà, âêëþ÷àåò ïîìåùåíèÿ Âåíãåðñêîé íàöèîíàëüíîé ãàëåðåè; íà÷àò â XIV â.; ïåðåñòðîåí â ñòèëå ðåíåññàíñà â XV-XVI ââ., â ñòèëå áàðîêêî â 1749-70 è â 1881-91, àðõèòåêòîðû Ì. Èáëü, À. Õàóñìàí; ðàçðóøåí â 1945, âîññòàíîâëåí ê 1967), æèëûå äîìà XIII-XVIII ââ., ãîòè÷åñêàÿ öåðêîâü Áîãîìàòåðè (Ìàòüÿøà; 1255-1470, îáíîâëåíà â êîíöå XIX â.), ìàâçîëåé Ãþëü-Áàáà è òóðåöêèå áàíè (XVI â.), öåðêîâü ñâ. Àííû â ñòèëå áàðîêêî (1740-62) è äð.  ðàéîíå Ïåøò: öåðêîâü Áåëüâàðîø (XV-XVIII ââ.), Öåíòðàëüíàÿ ðàòóøà (1727-47, áàðîêêî), Íàöèîíàëüíûé ìóçåé (1837-47, àðõèòåêòîð Ì. Ïîëëàê, êëàññèöèçì), êîíöåðòíûé çàë «Âèãàäî» (1858-64, íàöèîíàëüíàÿ ðîìàíòèêà), îïåðíûé òåàòð (1875-84, àðõèòåêòîð Èáëü, íåîðåíåññàíñ), Ìóçåé ïðèêëàäíîãî èñêóññòâà (1896, àðõèòåêòîð Ý. Ëåõíåð, ñòèëü «ìîäåðí»), ïàðëàìåíò (1884-96, ïñåâäîãîòèêà), áûâøèé äîì Ðîæàâ¸ëüäè (1910-19, àðõèòåêòîð Á. Ëàéòà) è çäàíèå Ìèíèñòåðñòâà òðàíñïîðòà (1939, îáå ïîñòðîéêè — â äóõå ñîâðåìåííîé àðõèòåêòóðû). Áåðåãà Äóíàÿ ñâÿçàíû 8 ìîñòàìè, ïåðåõîäÿùèìè â ìàãèñòðàëè Ïåøòà (â òîì ÷èñëå «Öåïíîé», 1839-40, «Ýðæåáåò», 1897-1903, ðàçðóøåí â 1944-45, âîññòàíîâëåí â 1955-65, è äð.). Ïîñëå Âòîðîé ìèðîâîé âîéíû 1939-45 ñîîðóæåíû Íàðîäíûé ñòàäèîí (1948-53), Äîì ïðîôñîþçîâ (1948-50), îòåëè «Áóäàïåøò» (1967), «Äóíà Èíòåðêîíòèíåíòàëü» (1969), «Ôîðóì» è «Àòðèóì» (îáå ïîñòðîéêè — êîíöà 70-õ — íà÷àëà 80-õ ãã.). Íà áûâøèõ îêðàèíàõ Áóäàïåøòà (ïðèãîðîäû ×åïåëü, Óéïåøò, Êèøïåøò, Áóäàôîê, Àòòèëà Éîæåô è äð., ñ 194 — â ÷åðòå Áóäàïåøòà) ñîçäàíû áëàãîóñòðîåííûå æèëûå ðàéîíû. Âåä¸òñÿ ñòðîèòåëüñòâî íîâûõ ëèíèé ìåòðîïîëèòåíà. Ìóçåé èçîáðàçèòåëüíûõ èñêóññòâ.

Âèä íà ðàéîí Ïåøò è çäàíèå ïàðëàìåíòà (1884 — 1896, àðõèòåêòîð È. Øòåéíäëü).

Ëèòåðàòóðà: Ä. Ãåëëåðò, Áóäàïåøò, ïåð. ñ âåíã., Ì., 1959; Áóäàïåøò. (Àëüáîì), ïåð. ñ âåíã., 2 èçä., Áóäàïåøò, 1972, Biczó Ò., Budapest…, (Bdpst), 1979. (Èñòî÷íèê: «Ïîïóëÿðíàÿ õóäîæåñòâåííàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ.» Ïîä ðåä. Ïîëåâîãî Â.Ì.; Ì.: Èçäàòåëüñòâî «Ñîâåòñêàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ», 1986.)

ÁÓÄÀÏÅØÒ —

(Budapest)

ñòîëèöà, ïîëèòè÷åñêèé, ýêîíîìè÷åñêèé è êóëüòóðíûé öåíòð Âåíãåðñêîé Íàðîäíîé Ðåñï… Áîëüøàÿ Ñîâåòñêàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

ÁÓÄÀÏÅØÒ — ÁÓÄÀÏÅØÒ, ñòîëèöà (ñ 1867) Âåíãðèè. 2,0 ìëí. æèòåëåé. Ïîðò íà Äóíàå; ìåæäóíàðîäíûé àýðîïîðò. Ìåòðîïî… Ñîâðåìåííàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

Подробная информация о фамилии Будапешт, а именно ее происхождение, история образования, суть фамилии, значение, перевод и склонение. Какая история происхождения фамилии Будапешт? Откуда родом фамилия Будапешт? Какой национальности человек с фамилией Будапешт? Как правильно пишется фамилия Будапешт? Верный перевод фамилии Будапешт на английский язык и склонение по падежам. Полную характеристику фамилии Будапешт и ее суть вы можете прочитать онлайн в этой статье совершенно бесплатно без регистрации.

Происхождение фамилии Будапешт

Большинство фамилий, в том числе и фамилия Будапешт, произошло от отчеств (по крестильному или мирскому имени одного из предков), прозвищ (по роду деятельности, месту происхождения или какой-то другой особенности предка) или других родовых имён.

История фамилии Будапешт

В различных общественных слоях фамилии появились в разное время. История фамилии Будапешт насчитывает долгую историю. Впервые фамилия Будапешт встречается в летописях духовенства с середины XVIII века. Обычно они образовались от названий приходов и церквей или имени отца. Некоторые священнослужители приобретали фамилии при выпуске из семинарии, при этом лучшим ученикам давались фамилии наиболее благозвучные и несшие сугубо положительный смысл, как например Будапешт. Фамилия Будапешт наследуется из поколения в поколение по мужской линии (или по женской).

Суть фамилии Будапешт по буквам

Фамилия Будапешт состоит из 8 букв. Восемь букв в фамилии означают, что это кто угодно, только не прирожденный «человек семьи». Такие люди постоянно испытывают чувство неудовлетворенности существующим положением вещей, они всегда в процессе поиска чего-то нового, яркого, способного вызвать восхищение. Сами же они – воплощенное очарование, в самом прямом смысле слова: способны околдовать, увлечь, лишить разума. Проанализировав значение каждой буквы в фамилии Будапешт можно понять ее суть и скрытое значение.

Значение фамилии Будапешт

Фамилия является основным элементом, связывающим человека со вселенной и окружающим миром. Она определяет его судьбу, основные черты характера и наиболее значимые события. Внутри фамилии Будапешт скрывается опыт, накопленный предыдущими поколениями и предками. По нумерологии фамилии Будапешт можно определить жизненный путь рода, семейное благополучие, достоинства, недостатки и характер носителя фамилии. Число фамилии Будапешт в нумерологии — 8. Люди с фамилией Будапешт рожденны под счастливой цифрой. Восьмерка является перевернутым символом бесконечности, а потому гарантирует своему носителю долгую жизнь. Позитивное влияние распространяется не только на продолжительность, но и качество жизни: большинство представителей фамилии Будапешт избавлены от материальных проблем и буквально купаются в благополучии.

Удачу и размеренное существование обеспечивают кольца Сатурна, который покровительствует этому числу. У носителей фамилии Будапешт нет ярких взлетов и ошеломительных падений. Их судьба – это классический сценарий успешного человека. Вначале успешная учеба и отличные оценки, затем – теплое место в фирме родителей или должность в компании хорошего знакомого. Высшие силы определили для людей с фамилией Будапешт особую роль, а потому от их решений и действий нередко зависит чья–то жизнь. На таких людей равняются другие и носители фамилии Будапешт должны соответствовать ожиданиям других.

В семейной жизни этих людей с фамилией Будапешт царит чудесная атмосфера: дом – полная чаша, любимая супруга – фотомодель с глянцевого журнала. На их столе – изысканные блюда, вкушаемые под классическую музыку. К сожалению, эта идиллия не является заслугой самих людей. Это дары высших сил, подаренные через близких родственников или лучших друзей.

И они знают об этом, а потому часто злятся на подобную предопределенность. Изменить что–либо они не в силах: вся накопленная злость выливается в мелкие интриги, случайные связи с противоположным полом и ссоры с подчиненными. Но в доме – человек с фамилией Будапешт снова пример для подражания, счастливые семьянины и гостеприимные хозяева.

Заранее начертанная линия судьбы заставляет людей с фамилией Будапешт искать способ самовыражения. Они мечтают о собственной карьере, славе и богатстве, добытых своими силами. Таким людям легко даются профессия музыканта, дизайнера или модельера. Они могут проявить себя в журналистике, юриспруденции и деловой сфере.

К достоинствам фамилии Будапешт можно отнести уравновешенность, великолепное чувство юмора, спокойствие и общительность. Эти люди умело поддерживают беседу, подмечают достоинства ближайшего окружения и с радостью дарят комплименты.

Как правильно пишется фамилия Будапешт

В русском языке грамотным написанием этой фамилии является — Будапешт. В английском языке фамилия Будапешт может иметь следующий вариант написания — Budapesht.

Склонение фамилии Будапешт по падежам

| Падеж | Вопрос | Фамилия |

| Именительный | Кто? | Будапешт |

| Родительный | Нет Кого? | Будапешт |

| Дательный | Рад Кому? | Будапешт |

| Винительный | Вижу Кого? | Будапешт |

| Творительный | Доволен Кем? | Будапешт |

| Предложный | Думаю О ком? | Будапешт |

Видео про фамилию Будапешт

Вы согласны с описанием фамилии Будапешт, ее происхождением, историей образования, значением и изложенной сутью? Какую информацию о фамилии Будапешт вы еще знаете? С какими известными и успешными людьми с фамилией Будапешт вы знакомы? Будем рады обсудить фамилию Будапешт более подробно с посетителями нашего сайта в комментариях.

Если вы нашли ошибку в описании фамилии, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

будапе́штский

будапе́штский (от Будапе́шт)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: проведывать — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Синонимы к слову «будапештский»

Предложения со словом «будапештский»

- Следующий сезон он работал с итальянской «Виченцей», а потом ненадолго возглавил будапештский «Гонвед».

- А потом, совсем в другом мире, – Будапештский медицинский университет.

- Они распустили будапештский и другие районные рабочие советы, находившиеся в руках контрреволюционеров, и упорно расширяют ряды социалистической рабочей партии.

- (все предложения)

|

Budapest |

|

|---|---|

|

Capital city |

|

| Capital City of Hungary Magyarország fővárosa |

|

|

Danube with Matthias Church in the background Buda Castle Hungarian Parliament Heroes’ Square St. Stephen’s Basilica |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Nicknames:

Heart of Europe, Queen of the Danube, Pearl of the Danube, Capital of Freedom, Capital of Spas and Thermal Baths, Capital of Festivals |

|

|

Budapest Location within Hungary Budapest Location within Europe |

|

| Coordinates: 47°29′33″N 19°03′05″E / 47.49250°N 19.05139°ECoordinates: 47°29′33″N 19°03′05″E / 47.49250°N 19.05139°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Central Hungary |

| Unification of Buda, Pest and Óbuda | 17 November 1873 |

| Boroughs |

23 Districts

|

| Government

[2] |

|

| • Type | Mayor – Council |

| • Body | General Assembly of Budapest |

| • Mayor | Gergely Karácsony (Dialogue) |

| Area

[3] |

|

| • Capital city | 525.2 km2 (202.8 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,538 km2 (980 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 7,626 km2 (2,944 sq mi) |

| Elevation

[6] |

Lowest (Danube) 96 m Highest (János Hill) 527 m (315 to 1,729 ft) |

| Population

(2017)[7][8] |

|

| • Capital city | 1,752,286[1] |

| • Rank | 1st (9th in EU) |

| • Density | 3,388/km2 (8,770/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,997,958[5] |

| • Metro | 3,011,598[4] |

| Demonyms | Budapester, budapesti (Hungarian) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code(s) |

1011–1239 |

| Area code | 1 |

| ISO 3166 code | HU-BU |

| NUTS code | HU101 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.901[9] – very high · 1st |

| Website | BudapestInfo Official Government Official |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Official name | Budapest, including the Banks of the Danube, the Buda Castle Quarter and Andrássy Avenue |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 400 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Extensions | 2002 |

| Area | 473.3 ha |

| Buffer zone | 493.8 ha |

Budapest (, ;[10][11][12] Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈbudɒpɛʃt] (listen)) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river;[13][14][15] the city has an estimated population of 1,752,286 over a land area of about 525 square kilometres (203 square miles).[16] Budapest, which is both a city and county, forms the centre of the Budapest metropolitan area, which has an area of 7,626 square kilometres (2,944 square miles) and a population of 3,303,786; it is a primate city, constituting 33% of the population of Hungary.[17][18]

The history of Budapest began when an early Celtic settlement transformed into the Roman town of Aquincum,[19][20] the capital of Lower Pannonia.[19] The Hungarians arrived in the territory in the late 9th century,[21] but the area was pillaged by the Mongols in 1241–42.[22] Re-established Buda became one of the centres of Renaissance humanist culture by the 15th century.[23][24][25] The Battle of Mohács, in 1526, was followed by nearly 150 years of Ottoman rule.[26] After the reconquest of Buda in 1686, the region entered a new age of prosperity, with Pest-Buda becoming a global city after the unification of Buda, Óbuda and Pest on 17 November 1873, with the name ‘Budapest’ given to the new capital.[16][27] Budapest also became the co-capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire,[28] a great power that dissolved in 1918, following World War I. The city was the focal point of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, the Battle of Budapest in 1945, as well as the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.[29][30]

Budapest is a global city with strengths in commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and entertainment.[31][32] Budapest is the headquarters of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology,[33] the European Police College[34] and the first foreign office of the China Investment Promotion Agency.[35] Over 40 colleges and universities are located in Budapest, including the Eötvös Loránd University, the Corvinus University, Semmelweis University, University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest and the Budapest University of Technology and Economics.[36][37] Opened in 1896,[38] the city’s subway system, the Budapest Metro, serves 1.27 million, while the Budapest Tram Network serves 1.08 million passengers daily.[39]

The central area of Budapest along the Danube River is classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has several notable monuments of classical architecture, including the Hungarian Parliament and the Buda Castle.[40] The city also has around 80 geothermal springs,[41] the largest thermal water cave system,[42] second largest synagogue, and third largest Parliament building in the world.[43] Budapest attracts around 12 million international tourists per year, making it a highly popular destination in Europe.[44]

Etymology and pronunciation[edit]

The previously separate towns of Buda, Óbuda, and Pest were officially unified in 1873[45] and given the new name Budapest. Before this, the towns together had sometimes been referred to colloquially as «Pest-Buda».[46][47] Pest is used pars pro toto for the entire city in contemporary colloquial Hungarian.[46]

All varieties of English pronounce the -s- as in the English word pest. The -u in Buda- is pronounced either /u/ like food (as in [48]) or /ju/ like cue (as in ). In Hungarian, the -s- is pronounced /ʃ/ as in wash; in IPA: Hungarian: [ˈbudɒpɛʃt] (listen).

The origins of the names «Buda» and «Pest» are obscure. Buda was

- probably the name of the first constable of the fortress built on the Castle Hill in the 11th century[49]

- or a derivative of Bod or Bud, a personal name of Turkic origin, meaning ‘twig’.[50]

- or a Slavic personal name, Buda, the short form of Budimír, Budivoj.[51]

Linguistically, however, a German origin through the Slavic derivative вода (voda, water) is not possible, and there is no certainty that a Turkic word really comes from the word buta ~ buda ‘branch, twig’.[52]

According to a legend recorded in chronicles from the Middle Ages, «Buda» comes from the name of its founder, Bleda, brother of Hunnic ruler Attila.

Attila went in the city of Sicambria in Pannonia, where he killed Buda, his brother, and he threw his corpse into the Danube. For while Attila was in the west, his brother crossed the boundaries in his reign, because he named Sicambria after his own name Buda’s Castle. And though King Attila forbade the Huns and the other peoples to call that city Buda’s Castle, but he called it Attila’s Capital, the Germans who were terrified by the prohibition named the city as Eccylburg, which means Attila Castle, however, the Hungarians did not care about the ban and call it Óbuda [Old Buda] and call it to this day.

The Scythians are certainly an ancient people and the strength of Scythia lies in the east, as we said above. And the first king of Scythia was Magog, son of Japhet, and his people were called Magyars [Hungarians] after their King Magog, from whose royal line the most renowned and mighty King Attila descended, who, in the 451st year of Our Lord’s birth, coming down from Scythia, entered Pannonia with a mighty force and, putting the Romans to flight, took the realm and made a royal residence for himself beside the Danube above the hot springs, and he ordered all the old buildings that he found there to be restored and he built them in a circular and very strong wall that in the Hungarian language is now called Budavár [Buda Castle] and by the Germans Etzelburg [Attila Castle]

There are several theories about Pest. One[55] states that the name derives from Roman times, since there was a local fortress (Contra-Aquincum) called by Ptolemy «Pession» («Πέσσιον», iii.7.§ 2).[56] Another has it that Pest originates in the Slavic word for cave, пещера, or peštera. A third cites пещ, or pešt, referencing a cave where fires burned or a limekiln.[57]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The first settlement on the territory of Budapest was built by Celts[19] before 1 AD. It was later occupied by the Romans. The Roman settlement – Aquincum – became the main city of Pannonia Inferior in 106 AD.[19] At first it was a military settlement, and gradually the city rose around it, making it the focal point of the city’s commercial life. Today this area corresponds to the Óbuda district within Budapest.[58] The Romans constructed roads, amphitheaters, baths and houses with heated floors in this fortified military camp.[59] The Roman city of Aquincum is the best-conserved of the Roman sites in Hungary. The archaeological site was turned into a museum with indoor and open-air sections.[60]

The Magyar tribes led by Árpád, forced out of their original homeland north of Bulgaria by Tsar Simeon after the Battle of Southern Buh, settled in the territory at the end of the 9th century displacing the founding Bulgarian settlers of the towns of Buda and Pest,[21][61] and a century later officially founded the Kingdom of Hungary.[21] Research places the probable residence of the Árpáds as an early place of central power near what became Budapest.[62] The Tatar invasion in the 13th century quickly proved it is difficult to defend a plain.[16][21] King Béla IV of Hungary, therefore, ordered the construction of reinforced stone walls around the towns[21] and set his own royal palace on the top of the protecting hills of Buda. In 1361 it became the capital of Hungary.[22][16]

The cultural role of Buda was particularly significant during the reign of King Matthias Corvinus. The Italian Renaissance had a great influence on the city. His library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was Europe’s greatest collection of historical chronicles and philosophic and scientific works in the 15th century, and second in size only to the Vatican Library.[16] After the foundation of the first Hungarian university in Pécs in 1367 (University of Pécs), the second one was established in Óbuda in 1395 (University of Óbuda).[63] The first Hungarian book was printed in Buda in 1473.[64] Buda had about 5,000 inhabitants around 1500.[65]

Retaking of Buda from the Ottoman Empire, painted by Frans Geffels in 1686

The Ottomans conquered Buda in 1526, as well in 1529, and finally occupied it in 1541.[66] The Turkish Rule lasted for more than 150 years.[16] The Ottoman Turks constructed many prominent bathing facilities within the city.[21] Some of the baths that the Turks erected during their rule are still in use 500 years later (Rudas Baths and Király Baths). By 1547 the number of Christians was down to about a thousand, and by 1647 it had fallen to only about seventy.[65] The unoccupied western part of the country became part of the Habsburg monarchy as Royal Hungary.

In 1686, two years after the unsuccessful siege of Buda, a renewed campaign was started to enter Buda. This time, the Holy League’s army was twice as large, containing over 74,000 men, including German, Croat, Dutch, Hungarian, English, Spanish, Czech, Italian, French, Burgundian, Danish and Swedish soldiers, along with other Europeans as volunteers, artillerymen, and officers. The Christian forces seized Buda, and in the next few years, all of the former Hungarian lands, except areas near Temesvár (Timișoara), were taken from the Turks. In the 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz, these territorial changes were officially recognized as the end of the rule of the Turks, and in 1718 the entire Kingdom of Hungary was removed from Ottoman rule.

Contemporary history after Unification[edit]

The 19th century was dominated by the Hungarian struggle for independence[16] and modernisation. The national insurrection against the Habsburgs began in the Hungarian capital in 1848 and was defeated one and a half years later, with the help of the Russian Empire. 1867 was the year of Reconciliation that brought about the birth of Austria-Hungary. This made Budapest the twin capital of a dual monarchy. It was this compromise which opened the second great phase of development in the history of Budapest, lasting until World War I. In 1849 the Chain Bridge linking Buda with Pest was opened as the first permanent bridge across the Danube[67] and in 1873 Buda and Pest were officially merged with the third part, Óbuda (Old Buda), thus creating the new metropolis of Budapest. The dynamic Pest grew into the country’s administrative, political, economic, trade and cultural hub. Ethnic Hungarians overtook Germans in the second half of the 19th century due to mass migration from the overpopulated rural Transdanubia and Great Hungarian Plain. Between 1851 and 1910 the proportion of Hungarians increased from 35.6% to 85.9%, Hungarian became the dominant language, and German was crowded out. The proportion of Jews peaked in 1900 with 23.6%.[68][69][70] Due to the prosperity and the large Jewish community of the city at the start of the 20th century, Budapest was often called the «Jewish Mecca»[22] or «Judapest».[71][72] Budapest also became an important center for the Aromanian diaspora during the 19th century.[73] In 1918, Austria-Hungary lost the war and collapsed; Hungary declared itself an independent republic (Republic of Hungary). In 1920 the Treaty of Trianon partitioned the country, and as a result, Hungary lost over two-thirds of its territory, and about two-thirds of its inhabitants, including 3.3 million out of 15 million ethnic Hungarians.[74][75]

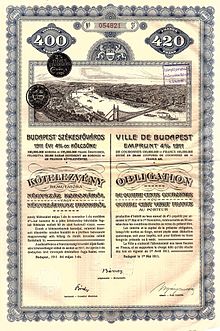

Bond of the City of Budapest, issued 1 May 1911

Soviet tanks in Budapest (1956)

In 1944, a year before the end of World War II, Budapest was partly destroyed by British and American air raids (first attack 4 April 1944[76][77][78]).

From 24 December 1944 to 13 February 1945, the city was besieged during the Battle of Budapest. Budapest sustained major damage caused by the attacking Soviet and Romanian troops and the defending German and Hungarian troops. More than 38,000 civilians died during the conflict. All bridges were destroyed by the Germans. The stone lions that have decorated the Chain Bridge since 1852 survived the devastation of the war.[79]

Between 20% and 40% of Greater Budapest’s 250,000 Jewish inhabitants died through Nazi and Arrow Cross Party, during the German occupation of Hungary, from 1944 to early 1945.[80]

Swiss diplomat Carl Lutz rescued tens of thousands of Jews by issuing Swiss protection papers and designating numerous buildings, including the now famous Glass House (Üvegház) at Vadász Street 29, to be Swiss protected territory. About 3,000 Hungarian Jews found refuge at the Glass House and in a neighboring building. Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg saved the lives of tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest by giving them Swedish protection papers and taking them under his consular protection.[81] Wallenberg was abducted by the Russians on 17 January 1945 and never regained freedom. Giorgio Perlasca, an Italian citizen, saved thousands of Hungarian Jews posing as a Spanish diplomat.[82][83] Some other diplomats also abandoned diplomatic protocol and rescued Jews. There are two monuments for Wallenberg, one for Carl Lutz and one for Giorgio Perlasca in Budapest.

Following the capture of Hungary from Nazi Germany by the Red Army, Soviet military occupation ensued, which ended only in 1991. The Soviets exerted significant influence on Hungarian political affairs. In 1949, Hungary was declared a communist People’s Republic (People’s Republic of Hungary). The new Communist government considered the buildings like the Buda Castle symbols of the former regime, and during the 1950s the palace was gutted and all the interiors were destroyed (also see Stalin era).

On 23 October 1956 citizens held a large peaceful demonstration in Budapest demanding democratic reform. The demonstrators went to the Budapest radio station and demanded to publish their demands. The regime ordered troops to shoot into the crowd. Hungarian soldiers gave rifles to the demonstrators who were now able to capture the building. This initiated the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. The demonstrators demanded to appoint Imre Nagy to be Prime Minister of Hungary. To their surprise, the central committee of the «Hungarian Working People’s Party» did so that same evening. This uprising was an anti-Soviet revolt that lasted from 23 October until 11 November. After Nagy had declared that Hungary was to leave the Warsaw Pact and become neutral, Soviet tanks and troops entered the country to crush the revolt. Fighting continued until mid November, leaving more than 3000 dead. A monument was erected at the fiftieth anniversary of the revolt in 2006, at the edge of the City Park. Its shape is a wedge with a 56 angle degree made in rusted iron that gradually becomes shiny, ending in an intersection to symbolize Hungarian forces that temporarily eradicated the Communist leadership.[84]

From the 1960s to the late 1980s Hungary was often satirically referred to as «the happiest barrack» within the Eastern bloc, and much of the wartime damage to the city was finally repaired. Work on Erzsébet Bridge, the last to be rebuilt, was finished in 1964. In the early 1970s, Budapest Metro’s east–west M2 line was first opened, followed by the M3 line in 1976. In 1987, Buda Castle and the banks of the Danube were included in the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites. Andrássy Avenue (including the Millennium Underground Railway, Hősök tere, and Városliget) was added to the UNESCO list in 2002. In the 1980s, the city’s population reached 2.1 million. In recent times a significant decrease in population occurred mainly due to a massive movement to the neighbouring agglomeration in Pest county, i.e., suburbanisation.[85]

In the last decades of the 20th century the political changes of 1989–90 (Fall of the Iron Curtain) concealed changes in civil society and along the streets of Budapest. The monuments of the dictatorship were removed from public places, into Memento Park. In the first 20 years of the new democracy, the development of the city was managed by its mayor, Gábor Demszky.[86]

Geography[edit]

Topography[edit]

Budapest, strategically placed at the centre of the Carpathian Basin, lies on an ancient route linking the hills of Transdanubia with the Great Plain. By road it is 216 kilometres (134 mi) south-east of Vienna, 545 kilometres (339 mi) south of Warsaw, 1,565 kilometres (972 mi) south-west of Moscow, 1,122 kilometres (697 mi) north of Athens, 788 kilometres (490 mi) north-east of Milan, and 443 kilometres (275 mi) south-east of Prague.[87]

The 525 square kilometres (203 sq mi) area of Budapest lies in Central Hungary, surrounded by settlements of the agglomeration in Pest county. The capital extends 25 and 29 km (16 and 18 mi) in the north–south, east–west direction respectively. The Danube enters the city from the north; later it encircles two islands, Óbuda Island and Margaret Island.[16] The third island Csepel Island is the largest of the Budapest Danube islands, however only its northernmost tip is within city limits. The river that separates the two parts of the city is 230 m (755 ft) wide at its narrowest point in Budapest. Pest lies on the flat terrain of the Great Plain while Buda is rather hilly.[16]

The wide Danube was always fordable at this point because of a small number of islands in the middle of the river. The city has marked topographical contrasts: Buda is built on the higher river terraces and hills of the western side, while the considerably larger Pest spreads out on a flat and featureless sand plain on the river’s opposite bank.[88] Pest’s terrain rises with a slight eastward gradient, so the easternmost parts of the city lie at the same altitude as Buda’s smallest hills, notably Gellért Hill and Castle Hill.[89]

The Buda hills consist mainly of limestone and dolomite, the water created speleothems, the most famous ones being the Pálvölgyi cave (total length 7,200 m or 23,600 ft) and the Szemlőhegyi cave (total length 2,200 m or 7,200 ft). The hills were formed in the Triassic Period. The highest point of the hills and of Budapest is János Hill, at 527 metres (1,729 feet) above sea level. The lowest point is the line of the Danube which is 96 metres (315 feet) above sea level. Budapest is also rich in green areas. Of the 525 square kilometres (203 square miles) occupied by the city, 83 square kilometres (32 square miles) is green area, park and forest.[90] The forests of Buda hills are environmentally protected.[91]

The city’s importance in terms of traffic is very central, because many major European roads and European railway lines lead to Budapest.[89] The Danube was and is still an important water-way and this region in the centre of the Carpathian Basin lies at the cross-roads of trade routes.[92]

Budapest is one of only three capital cities in the world which has thermal springs (the others being Reykjavík in Iceland and Sofia in Bulgaria). Some 125 springs produce 70 million litres (15,000,000 imperial gallons; 18,000,000 US gallons) of thermal water a day, with temperatures ranging up to 58 Celsius. Some of these waters have been claimed to have medicinal effects due to their high mineral contents.[89]

Climate[edit]

Budapest has a humid subtropical climate when the 0 °C isotherm is used and warm summers (near of an oceanic climate) according to the 1971–2000 climatological norm.[93] Winter (November until early March) can be cold and the city receives little sunshine. Snowfall is fairly frequent in most years, and nighttime temperatures of −10 °C (14 °F) are not uncommon between mid-December and mid-February. The spring months (March and April) see variable conditions, with a rapid increase in the average temperature. The weather in late March and in April is often very agreeable during the day and fresh at night. Budapest’s long summer – lasting from May until mid-September – is warm or very warm. Sudden heavy showers also occur, particularly in May and June. The autumn in Budapest (mid-September until late October) is characterised by little rain and long sunny days with moderate temperatures. Temperatures often turn abruptly colder in late October or early November.

Mean annual precipitation in Budapest is around 23.5 inches (596.9 mm). On average, there are 84 days with precipitation and 1988 hours of sunshine (of a possible 4383) each year.[3][94][95] From March to October, average sunshine totals are roughly equal to those seen in northern Italy (Venice).

The city lies on the boundary between Zone 6 and Zone 7 in terms of the hardiness zone.[96][97]

| Climate data for Budapest, 1991–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.7 (105.3) |

39.4 (102.9) |

35.2 (95.4) |

30.8 (87.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.9 (73.2) |

26.6 (79.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

3.4 (38.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.2 (45.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

0.1 (32.2) |

3.6 (38.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.6 (−14.1) |

−23.4 (−10.1) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37 (1.5) |

29 (1.1) |

30 (1.2) |

42 (1.7) |

62 (2.4) |

63 (2.5) |

45 (1.8) |

49 (1.9) |

40 (1.6) |

39 (1.5) |

53 (2.1) |

43 (1.7) |

532 (20.9) |

| Average precipitation days | 7.3 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 7.8 | 7.2 | 84 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 74 | 66 | 59 | 61 | 61 | 59 | 61 | 67 | 72 | 78 | 80 | 68.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 62 | 93 | 137 | 177 | 234 | 250 | 271 | 255 | 187 | 141 | 69 | 52 | 1,988 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source: Average temperatures 1991-2020: OMSZ — Hungarian Meteorological Service.[98] |

Architecture[edit]

Budapest has architecturally noteworthy buildings in a wide range of styles and from distinct time periods, from the ancient times as Roman City of Aquincum in Óbuda (District III), which dates to around 89 AD, to the most modern Palace of Arts, the contemporary arts museum and concert hall.[101][102][103]

Most buildings in Budapest are relatively low: in the early 2010s there were around 100 buildings higher than 45 metres (148 ft). The number of high-rise buildings is kept low by building legislation, which is aimed at preserving the historic cityscape and to meet the requirements of the World Heritage Site. Strong rules apply to the planning, authorisation and construction of high-rise buildings and consequently much of the inner city does not have any. Some planners would like see an easing of the rules for the construction of skyscrapers, and the possibility of building skyscrapers outside the city’s historic core has been raised.[104][105]

In the chronological order of architectural styles Budapest is represented on the entire timeline, starting with the Roman City of Aquincum representing ancient architecture.

The next determinative style is the Gothic architecture in Budapest. The few remaining Gothic buildings can be found in the Castle District. Buildings of note are no. 18, 20 and 22 on Országház Street, which date back to the 14th century and No. 31 Úri Street, which has a Gothic façade that dates back to the 15th century. Other buildings with Gothic features are the Inner City Parish Church, built in the 12th century,[106] and the Mary Magdalene Church, completed in the 15th century.[107] The most characteristic Gothic-style buildings are actually Neo-Gothic, like the most well-known Budapest landmarks, the Hungarian Parliament Building[108] and the Matthias Church, where much of the original material was used (originally built in Romanesque style in 1015).[109]

The next chapter in the history of human architecture is Renaissance architecture. One of the earliest places to be influenced by the Renaissance style of architecture was Hungary, and Budapest in particular. The style appeared following the marriage of King Matthias Corvinus and Beatrice of Naples in 1476. Many Italian artists, craftsmen and masons came to Buda with the new queen. Today, many of the original renaissance buildings disappeared during the varied history of Buda, but Budapest is still rich in renaissance and neo-renaissance buildings, like the famous Hungarian State Opera House, St. Stephen’s Basilica and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.[110]

During the Turkish occupation (1541–1686), Islamic culture flourished in Budapest; multiple mosques and baths were built in the city. These were great examples of Ottoman architecture, which was influenced by Muslims from around the world including Turkish, Iranian, Arabian and to a larger extent, Byzantine architecture as well as Islamic traditions. After the Holy League conquered Budapest, they replaced most of the mosques with churches and minarets were turned into bell towers and cathedral spires. At one point the distinct sloping central square in Budapest became a bustling Oriental bazaar, which was filled with «the chatter of camel caravans on their way to Yemen and India».[111] Budapest is in fact one of the few places in the world with functioning original Turkish bathhouses dating back to the 16th century, like Rudas Baths or Király Baths. Budapest is home to the northernmost place where the tomb of influential Islamic Turkish Sufi Dervish, Gül Baba is found. Various cultures converged in Hungary seemed to coalesce well with each other, as if all these different cultures and architecture styles are digested into Hungary’s own way of cultural blend. A precedent to show the city’s self-conscious is the top section of the city’s main square, named as Szechenyi. When Turks came to the city, they built mosques here which was aggressively replaced with Gothic church of St. Bertalan. The rationale of reusing the base of the former Islamic building mosque and reconstruction into Gothic Church but Islamic style architecture over it is typically Islamic are still visible. An official term for the rationale is spolia. The mosque was called the djami of Pasha Gazi Kassim, and djami means mosque in Arabic. After Turks and Muslims were expelled and massacred from Budapest, the site was reoccupied by Christians and reformed into a church, the Inner City Parish Church (Budapest). The minaret and Turkish entranceway were removed. The shape of the architecture is its only hint of exotic past—»two surviving prayer niches facing Mecca and an ecumenical symbol atop its cupola: a cross rising above the Turkish crescent moon».[111]

After 1686, the Baroque architecture designated the dominant style of art in catholic countries from the 17th century to the 18th century.[112] There are many Baroque-style buildings in Budapest and one of the finest examples of preserved Baroque-style architecture is the Church of St. Anna in Batthyhány square. An interesting part of Budapest is the less touristy Óbuda, the main square of which also has some beautiful preserved historic buildings with Baroque façades. The Castle District is another place to visit where the best-known landmark Buda Royal Palace and many other buildings were built in the Baroque style.[112]

The Classical architecture and Neoclassical architecture are the next in the timeline. Budapest had not one but two architects that were masters of the Classicist style. Mihály Pollack (1773–1855) and József Hild (1789–1867), built many beautiful Classicist-style buildings in the city. Some of the best examples are the Hungarian National Museum, the Lutheran Church of Budavár (both designed by Pollack) and the seat of the Hungarian president, the Sándor Palace. The most iconic and widely known Classicist-style attraction in Budapest is the Széchenyi Chain Bridge.[113] Budapest’s two most beautiful Romantic architecture buildings are the Great Synagogue in Dohány Street and the Vigadó Concert Hall on the Danube Promenade, both designed by architect Frigyes Feszl (1821–1884). Another noteworthy structure is the Budapest Western Railway Station, which was designed by August de Serres and built by the Eiffel Company of Paris in 1877.[114]

Art Nouveau came into fashion in Budapest by the exhibitions which were held in and around 1896 and organised in connection with the Hungarian Millennium celebrations.[115] Art Nouveau in Hungary (Szecesszió in Hungarian) is a blend of several architectural styles, with a focus on Hungary’s specialities. One of the leading Art Nouveau architects, Ödön Lechner (1845–1914), was inspired by Indian and Syrian architecture as well as traditional Hungarian decorative designs. One of his most beautiful buildings in Budapest is the Museum of Applied Arts. Another examples for Art Nouveau in Budapest is the Gresham Palace in front of the Chain Bridge, the Hotel Gellért, the Franz Liszt Academy of Music or Budapest Zoo and Botanical Garden.[101]

It is one of the world’s outstanding urban landscapes and illustrates the great periods in the history of the Hungarian capital.

UNESCO[116]

The second half of the 20th century also saw, under the communist regime, the construction of blocks of flats (panelház), as in other Eastern European countries. In the 21st century, Budapest faces new challenges in its architecture. The pressure towards the high-rise buildings is unequivocal among today’s world cities, but preserving Budapest’s unique cityscape and its very diverse architecture, along with green areas, is force Budapest to balance between them. The Contemporary architecture has wide margin in the city. Public spaces attract heavy investment by business and government also, so that the city has gained entirely new (or renovated and redesigned) squares, parks and monuments, for example the city central Kossuth Lajos square, Deák Ferenc square and Liberty Square. Numerous landmarks are created in the last decade in Budapest, like the National Theatre, Palace of Arts, Rákóczi Bridge, Megyeri Bridge, Budapest Airport Sky Court among others, and millions of square meters of new office buildings and apartments. But there are still large opportunities in real estate development in the city.[117][118][119]

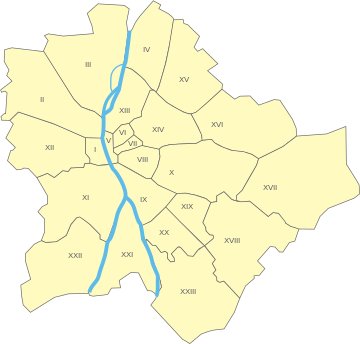

Districts[edit]

|

Budapest’s twenty-three districts overview |

||||

| Administration | Population | Area and Density | ||

| District | Official name | Official 2013 | Km2 | People/km2 |

| I | Várkerület | 24.528 | 3,41 | 7.233 |

| II | Rózsadomb | 88.011 | 36,34 | 2.426 |

| III | Óbuda-Békásmegyer | 123.889 | 39,69 | 3.117 |

| IV | Újpest | 99.050 | 18,82 | 5.227 |

| V | Belváros-Lipótváros | 27.342 | 2,59 | 10.534 |

| VI | Terézváros | 43.377 | 2,38 | 18.226 |

| VII | Erzsébetváros | 64.767 | 2,09 | 30.989 |

| VIII | Józsefváros | 85.173 | 6,85 | 11.890 |

| IX | Ferencváros | 63.697 | 12,53 | 4.859 |

| X | Kőbánya | 81.475 | 32,5 | 2.414 |

| XI | Újbuda | 145.510 | 33,47 | 4.313 |

| XII | Hegyvidék | 55.776 | 26,67 | 2.109 |

| XIII | Angyalföld, Göncz Árpád városközpont, Újlipótváros, Vizafogó |

118.320 | 13,44 | 8.804 |

| XIV | Zugló | 123.786 | 18,15 | 6.820 |

| XV | Rákospalota, Pestújhely, Újpalota | 79.779 | 26,95 | 2.988 |

| XVI | Árpádföld, Cinkota, Mátyásföld, Sashalom, Rákosszentmihály |

68.235 | 33,52 | 2.037 |

| XVII | Rákosmente | 78.537 | 54.83 | 1.418 |

| XVIII | Pestszentlőrinc-Pestszentimre | 94.663 | 38,61 | 2.414 |

| XIX | Kispest | 62.210 | 9,38 | 6.551 |

| XX | Pesterzsébet | 63.887 | 12,18 | 5.198 |

| XXI | Csepel | 76.976 | 25,75 | 2.963 |

| XXII | Budafok-Tétény | 51.071 | 34,25 | 1.473 |

| XXIII | Soroksár | 19.982 | 40,78 | 501 |

|

|

1,740,041 | 525.2 | 3,313.1 | |

|

Hungary |

9,937,628 | 93,030 | 107.2 | |

| Source: Eurostat,[120] HSCO[7] |

Most of today’s Budapest is the result of a late-nineteenth-century renovation, but the wide boulevards laid out then only bordered and bisected much older quarters of activity created by centuries of Budapest’s city evolution.

Budapest’s vast urban area is often described using a set of district names. These are either informal designations, reflect the names of villages that have been absorbed by sprawl, or are superseded administrative units of former boroughs.[121]

Such names have remained in use through tradition, each referring to a local area with its own distinctive character, but without official boundaries.[122]

Originally Budapest had 10 districts after coming into existence upon the unification of the three cities in 1873. Since 1950, Greater Budapest has been divided into 22 boroughs (and 23 since 1994). At that time there were changes both in the order of districts and in their sizes. The city now consists of 23 districts, 6 in Buda, 16 in Pest and 1 on Csepel Island between them.

The city centre itself in a broader sense comprises the District V, VI, VII, VIII, IX[123] and XIII on the Pest side, and the I, II, XI and XII on the Buda side of the city.[124]

District I is a small area in central Buda, including the historic Buda Castle. District II is in Buda again, in the northwest, and District III stretches along in the northernmost part of Buda. To reach District IV, one must cross the Danube to find it in Pest (the eastern side), also at north. With District V, another circle begins, it is located in the absolute centre of Pest. Districts VI, VII, VIII and IX are the neighbouring areas to the east, going southwards, one after the other.

District X is another, more external circle also in Pest, while one must jump to the Buda side again to find Districts XI and XII, going northwards. No more districts remaining in Buda in this circle, we must turn our steps to Pest again to find Districts XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX and XX (mostly external city parts), almost regularly in a semicircle, going southwards again.

District XXI is the extension of the above route over a branch of the Danube, the northern tip of a long island south from Budapest. District XXII is still on the same route in southwest Buda, and finally District XXIII is again in southernmost Pest, irregular only because it was part of District XX until 1994.[125]

Demographics[edit]

|

Budapest compared to Hungary and EU |

|||

| Budapest | Hungary | European Union | |

| Total Population | 1,763,913 | 9,937,628 | 507,890,191 |

| Population change, 2004 to 2014 | +2.7%[126] | −1.6%[126] | +2.2%[127] |

| Population density | 3,314 /km2 | 107 /km2 | 116 /km2 |

| GDP per capita PPP | $52,770 [128] | $33,408 [129] | $33,084 [130] |

| Bachelor’s Degree or higher | 34.1%[131] | 19.0%[131] | 27.1%[132] |

| Foreign born | 7.3%[133] | 1.7%[134] | 6.3%[135] |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1784 | 57,100 | — |

| 1850 | 206,339 | +261.4% |

| 1870 | 302,086 | +46.4% |

| 1880 | 402,706 | +33.3% |

| 1890 | 560,079 | +39.1% |

| 1900 | 861,434 | +53.8% |

| 1910 | 1,110,453 | +28.9% |

| 1920 | 1,232,026 | +10.9% |

| 1930 | 1,442,869 | +17.1% |

| 1941 | 1,712,791 | +18.7% |

| 1949 | 1,590,316 | −7.2% |

| 1955 | 1,713,552 | +7.7% |

| 1960 | 1,804,606 | +5.3% |

| 1965 | 1,877,916 | +4.1% |

| 1970 | 1,945,083 | +3.6% |

| 1980 | 2,059,226 | +5.9% |

| 1990 | 2,005,028 | −2.6% |

| 2001 | 1,773,401 | −11.6% |

| 2011 | 1,730,117 | −2.4% |

| 2021 | 1,771,865 | +2.4% |

| 1784,[136] Population 2001 to 2019[126] Present-territory of Budapest Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. |

Budapest is the most populous city in Hungary and one of the largest cities in the European Union, with a growing number of inhabitants, estimated at 1,763,913 in 2019,[137] whereby inward migration exceeds outward migration.[13] These trends are also seen throughout the Budapest metropolitan area, which is home to 3.3 million people.[138][139] This amounts to about 34% of Hungary’s population.

In 2014, the city had a population density of 3,314 people per square kilometre (8,580/sq mi), rendering it the most densely populated of all municipalities in Hungary. The population density of Elisabethtown-District VII is 30,989/km2 (80,260/sq mi), which is the highest population density figure in Hungary and one of the highest in the world, for comparison the density in Manhattan is 25,846/km2.[140]

Budapest is the fourth most «dynamically growing city» by population in Europe,[141] and the Euromonitor predicts a population increase of almost 10% between 2005 and 2030.[142] The European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion says Budapest’s population will increase by 10% to 30% only due to migration by 2050.[143] A constant inflow of migrants in recent years has fuelled population growth in Budapest. Productivity gains and the relatively large economically active share of the population explain why household incomes have increased in Budapest to a greater extent than in other parts of Hungary. Higher incomes in Budapest are reflected in the lower share of expenditure the city’s inhabitants allocate to necessity spending such as food and non-alcoholic drinks.[138]

At the 2016 microcensus, there were 1,764,263 people with 907,944 dwellings living in Budapest.[144] Some 1.6 million persons from the metropolitan area may be within Budapest’s boundaries during work hours, and during special events. This fluctuation of people is caused by hundreds of thousands of suburban residents who travel to the city for work, education, health care, and special events.[145]

By ethnicity there were 1,697,039 (96.2%) Hungarians, 34,909 (2%) Germans, 16,592 (0.9%) Romani, 9,117 (0.5%) Romanians and 5,488 (0.3%) Slovaks.[146] In Hungary people can declare multiple ethnic identities, hence the sum may exceed 100%.[147] The share of ethnic Hungarians in Budapest (96.2%) is slightly lower than the national average (98.3%) due to the international migration.[147]

According to the 2011 census, 1,712,153 people (99.0%) speak Hungarian, of whom 1,692,815 people (97.9%) speak it as a first language, while 19,338 people (1.1%) speak it as a second language. Other spoken (foreign) languages were: English (536,855 speakers, 31.0%), German (266,249 speakers, 15.4%), French (56,208 speakers, 3.3%) and Russian (54,613 speakers, 3.2%).[133]

According to the same census, 1,600,585 people (92.6%) were born in Hungary, 126,036 people (7.3%) outside Hungary while the birthplace of 2,419 people (0.1%) was unknown.[133]

Although only 1.7% of the population of Hungary in 2009 were foreigners, 43% of them lived in Budapest, making them 4.4% of the city’s population (up from 2% in 2001).[134] Nearly two-thirds of foreigners living in Hungary were under 40 years old. The primary motivation for this age group living in Hungary was employment.[134]

Budapest is home to one of the most populous Christian communities in Central Europe, numbering 698,521 people (40.4%) in 2011.[133] According to the 2011 census, there were 501,117 (29.0%) Roman Catholics, 146,756 (8.5%) Calvinists, 30,293 (1.8%) Lutherans, 16,192 (0.9%) Greek Catholics, 7,925 (0.5%) Jews and 3,710 (0.2%) Orthodox in Budapest. 395,964 people (22.9%) were irreligious while 585,475 people (33.9%) did not declare their religion.[133] The city is also home to one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe.[148]

Economy[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (September 2018) |

Budapest is a significant economic hub, classified as a Beta + world city in the study by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network and it is the second fastest-developing urban economy in Europe as GDP per capita in the city increased by 2.4 per cent and employment by 4.7 per cent compared to the previous year in 2014.[149][32]

On national level, Budapest is the primate city of Hungary regarding business and economy, accounting for 39% of the national income, the city has a gross metropolitan product more than $100 billion in 2015, making it one of the largest regional economy in the European Union.[150]

According to the Eurostat GDP per capita in purchasing power parity is 147% of the EU average in Budapest, which means €37,632 ($42,770) per capita.[128]

Budapest is also among the Top100 GDP performing cities in the world, measured by PricewaterhouseCoopers.

The city was named as the 52nd most important business centre in the world in the Worldwide Centres of Commerce Index, ahead of Beijing, São Paulo or Shenzhen and ranking 3rd (out of 65 cities) on MasterCard Emerging Markets Index.[151][152]

The city is 48th on the UBS The most expensive and richest cities in the world list, standing before cities such as Prague, Shanghai, Kuala Lumpur or Buenos Aires.[153]

In a global city competitiveness ranking by EIU, Budapest stands before Tel Aviv, Lisbon, Moscow and Johannesburg among others.[154]

The city is a major centre for banking and finance, real estate, retailing, trade, transportation, tourism, new media as well as traditional media, advertising, legal services, accountancy, insurance, fashion and the arts in Hungary and regionally. Budapest is home not only to almost all national institutions and government agencies, but also to many domestic and international companies, in 2014 there are 395.804 companies registered in the city.[155] Most of these entities are headquartered in the Budapest’s Central Business District, in the District V and District XIII. The retail market of the city (and the country) is also concentrated in the downtown, among others through the two largest shopping centres in Central and Eastern Europe, the 186,000 sqm WestEnd City Center and the 180,000 sqm Arena Plaza.[156][157]

Budapest has notable innovation capabilities as a technology and start-up hub. Many start-ups are headquartered and begin their business in the city, some of the best known examples are Prezi, LogMeIn or NNG. Budapest is the highest ranked Central and Eastern European city on Innovation Cities’ Top 100 index.[158] A good indicator of the city’s potential for innovation and research also, is that the European Institute of Innovation and Technology chose Budapest for its headquarters, along with the UN, which Regional Representation for Central Europe office is in the city, responsible for UN operations in seven countries.[159]

Moreover, the global aspect of the city’s research activity is shown through the establishment of the European Chinese Research Institute in the city.[160] Other important sectors include also, as natural science research, information technology and medical research, non-profit institutions, and universities. The leading business schools and universities in Budapest, the Budapest Business School, the CEU Business School and Corvinus University of Budapest offers a whole range of courses in economics, finance and management in English, French, German and Hungarian.[161] The unemployment rate is far the lowest in Budapest within Hungary, it was 2.7%, besides the many thousands of employed foreign citizens.[162]

Budapest is among the 25 most visited cities in the world, the city welcoming more than 4.4 million international visitors each year,[163] therefore the traditional and the congress tourism industry also deserve a mention, it contributes greatly to the city’s economy. The capital being home to many convention centres and thousands of restaurants, bars, coffee houses and party places, besides the full assortment of hotels. In restaurants offerings can be found of the highest quality Michelin-starred restaurants, like Onyx, Costes, Tanti or Borkonyha. The city ranked as the most liveable city in Central and Eastern Europe on EIU’s quality of life index in 2010.

Finance and corporate location[edit]

Budapest Stock Exchange, key institution of the publicly offered securities in Hungary and Central and Eastern Europe is situated in Budapest’s CBD at Liberty Square. BSE also trades other securities such as government bonds and derivatives such as stock options. Large Hungarian multinational corporations headquartered in Budapest are listed on BSE, for instance the Fortune Global 500 firm MOL Group, the OTP Bank, FHB Bank, Gedeon Richter, Magyar Telekom, CIG Pannonia, Zwack Unicum and more.[164]

Nowadays nearly all branches of industry can be found in Budapest, there is no particularly special industry in the city’s economy, but the financial centre role of the city is strong, nearly 40 major banks are presented in the city,[165] also those like Bank of China, KDB Bank and Hanwha Bank, which is unique in the region.

Also support the financial industry of Budapest, the firms of international banks and financial service providers, such as Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, GE Capital, Deutsche Bank, Sberbank, ING Group, Allianz, KBC Group, UniCredit and MSCI among others. Another particularly strong industry in the capital city is biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry, these are also traditionally strong in Budapest, through domestic companies, as Egis, Gedeon Richter, Chinoin and through international biotechnology corporations, like Pfizer, Teva, Novartis, Sanofi, who are also has R&D and production division here. Further high-tech industries, such as software development, engineering notable as well, the Nokia, Ericsson, Bosch, Microsoft, IBM employs thousands of engineers in research and development in the city. Game design also highly represented through headquarters of domestic Digital Reality, Black Hole and studio of Crytek or Gameloft. Beyond the above, there are regional headquarters of global firms, such as Alcoa, General Motors, General Electric, ExxonMobil, BP, BT, Flextronics, Panasonic, Huawei, Knorr-Bremse, Liberty Global, Tata Consultancy, Aegon, WizzAir, TriGránit, MVM Group, Graphisoft, there is a base for Nissan CEE, Volvo, Saab, Ford, including but not limited to.

Politics and government[edit]

As the capital of Hungary, Budapest is the seat of the country’s national government. The President of Hungary resides at the Sándor Palace in the District I (Buda Castle District),[166] while the office of the Hungarian Prime Minister is in the Carmelite Monastery in the Castle District.[167] Government ministries are all located in various parts of the city, most of them are in the District V, Leopoldtown. The National Assembly is seated in the Hungarian Parliament, which also located in the District V.[168] The President of the National Assembly, the third-highest public official in Hungary, is also seated in the largest building in the country, in the Hungarian Parliament.

Hungary’s highest courts are located in Budapest. The Curia (supreme court of Hungary), the highest court in the judicial order, which reviews criminal and civil cases, is located in the District V, Leopoldtown. Under the authority of its president it has three departments: criminal, civil and administrative-labour law departments. Each department has various chambers. The Curia guarantees the uniform application of law. The decisions of the Curia on uniform jurisdiction are binding for other courts.[169]

The second most important judicial authority, the National Judicial Council, is also housed in the District V, with the tasks of controlling the financial management of the judicial administration and the courts and giving an opinion on the practice of the president of the National Office for the Judiciary and the Curia deciding about the applications of judges and court leaders, among others.[170]

The Constitutional Court of Hungary is one of the highest level actors independent of the politics in the country. The Constitutional Court serves as the main body for the protection of the Constitution, its tasks being the review of the constitutionality of statutes. The Constitutional Court performs its tasks independently. With its own budget and its judges being elected by Parliament it does not constitute a part of the ordinary judicial system. The constitutional court passes on the constitutionality of laws, and there is no right of appeal on these decisions.[171]

Budapest hosts the main and regional headquarters of many international organizations as well, including United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, European Institute of Innovation and Technology, European Police Academy, International Centre for Democratic Transition, Institute of International Education, International Labour Organization, International Organization for Migration, International Red Cross, Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe, Danube Commission and even others.[172] The city is also home to more than 100 embassies and representative bodies as an international political actor.

Environmental issues have a high priority among Budapest’s politics. Institutions such as the Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe, located in Budapest, are very important assets.[173]

To decrease the use of cars and greenhouse gas emissions, the city has worked to improve public transportation, and nowadays the city has one of the highest mass transit usage in Europe. Budapest has one of the best public transport systems in Europe with an efficient network of buses, trolleys, trams and subway. Budapest has an above-average proportion of people commuting on public transport or walking and cycling for European cities.[174]

Riding on bike paths is one of the best ways to see Budapest – there are about 180 kilometres (110 miles) of bicycle paths in the city, fitting into the EuroVelo system.[175]

Crime in Budapest is investigated by different bodies. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime notes in their 2011 Global Study on Homicide that, according to criminal justice sources, the homicide rate in Hungary, calculated based on UN population estimates, was 1.4 in 2009, compared to Canada’s rate of 1.8 that same year.[176]

The homicide rate in Budapest is below the EU capital cities’ average according to WHO also.[177] However, organised crime is associated with the city, the Institute of Defence in a UN study named Budapest as one of the «global epicentres» of illegal pornography, money laundering and contraband tobacco, and also a negotiation center for international crime group leaders.[178]

City governance[edit]

|

Composition of the 33 seats in the General Assembly |

||

| Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Union | 13 seats | |

| Hungarian Socialist Party | 7 seats | |

| Momentum | 4 seats | |

| Democratic Coalition | 4 seats | |

| Párbeszéd | Mayor + 1 seat | |

| Independent | 3 seats |

Budapest has been a metropolitan municipality with a mayor-council form of government since its consolidation in 1873, but Budapest also holds a special status as a county-level government, and also special within that, as holds a capital-city territory status.[179] In Budapest, the central government is responsible for the urban planning, statutory planning, public transport, housing, waste management, municipal taxes, correctional institutions, libraries, public safety, recreational facilities, among others. The Mayor is responsible for all city services, police and fire protection, enforcement of all city and state laws within the city, and administration of public property and most public agencies. Besides, each of Budapest’ twenty-three districts has its own town hall and a directly elected council and the directly elected mayor of district.[2]

The Mayor of Budapest is Gergely Karácsony who was elected on 13 October 2019. The mayor and members of General Assembly are elected to five-year terms.[2]

The Budapest General Assembly is a unicameral body consisting of 33 members, which consist of the 23 mayors of the districts, 9 from the electoral lists of political parties, plus Mayor of Budapest (the Mayor is elected directly). Each term for the mayor and assembly members lasts five years.[180] Submitting the budget of Budapest is the responsibility of the Mayor and the deputy-mayor in charge of finance. The latest, 2014 budget was approved with 18 supporting votes from ruling Fidesz and 14 votes against by the opposition lawmakers.[181]

Main sights and tourism[edit]

Budapest is widely known for its well-kept pre-war cityscape, with a great variety of streets and landmarks in classical architecture.

The most well-known sight of the capital is the neo-Gothic Parliament, the biggest building in Hungary with its 268 metres (879 ft) length, also holding (since 2001) the Hungarian Crown Jewels.

Saint Stephen’s Basilica is the most important religious building of the city, where the Holy Right Hand of Hungary’s first king, Saint Stephen is on display as well.

The Hungarian cuisine and café culture can be seen and tasted in a lot of places, like Gerbeaud Café, the Százéves, Biarritz, Fortuna, Alabárdos, Arany Szarvas, Kárpátia and the world-famous Mátyás-pince [hu] restaurants and beer bars.

There are Roman remains at the Aquincum Museum, and historic furniture at the Nagytétény Castle Museum, just 2 out of 223 museums in Budapest. Another historical museum is the House of Terror, hosted in the building that was the venue of the Nazi Headquarters. The Castle Hill, the River Danube embankments and the whole of Andrássy út have been officially recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Castle Hill and the Castle District; there are three churches here, six museums, and a host of interesting buildings, streets and squares. The former Royal Palace is one of the symbols of Hungary – and has been the scene of battles and wars ever since the 13th century. Nowadays it houses two museums and the National Széchenyi Library. The nearby Sándor Palace contains the offices and official residence of the President of Hungary. The seven-hundred-year-old Matthias Church is one of the jewels of Budapest, it is in neo-Gothic style, decorated with coloured shingles and elegant pinnacles. Next to it is an equestrian statue of the first king of Hungary, King Saint Stephen, and behind that is the Fisherman’s Bastion, built in 1905 by the architect Frigyes Schulek, the Fishermen’s Bastions owes its name to the namesake corporation that during the Middle Ages was responsible of the defence of this part of ramparts, from where opens out a panoramic view of the whole city. Statues of the Turul, the mythical guardian bird of Hungary, can be found in both the Castle District and the Twelfth District.

In Pest, arguably the most important sight is Andrássy út. This Avenue is an elegant 2.5 kilometres (2 miles) long tree-lined street that covers the distance from Deák Ferenc tér to the Heroes Square. This Avenue overlooks many important sites. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. As far as Kodály körönd and Oktogon both sides are lined with large shops and flats built close together. Between there and Heroes’ Square the houses are detached and altogether grander. Under the whole runs continental Europe’s oldest Underground railway, most of whose stations retain their original appearance. Heroes’ Square is dominated by the Millenary Monument, with the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in front. To the sides are the Museum of Fine Arts and the Kunsthalle Budapest, and behind City Park opens out, with Vajdahunyad Castle. One of the jewels of Andrássy út is the Hungarian State Opera House. Statue Park, a theme park with striking statues of the Communist era, is located just outside the main city and is accessible by public transport.

The Dohány Street Synagogue is the largest synagogue in Europe, and the second largest active synagogue in the world.[182] The synagogue is located in the Jewish district taking up several blocks in central Budapest bordered by Király utca, Wesselényi utca, Grand Boulevard and Bajcsy Zsilinszky road. It was built in moorish revival style in 1859 and has a seating capacity of 3,000. Adjacent to it is a sculpture reproducing a weeping willow tree in steel to commemorate the Hungarian victims of the Holocaust.

The city is also home to the largest medicinal bath in Europe (Széchenyi Medicinal Bath) and the third largest Parliament building in the world, once the largest in the world. Other attractions are the bridges of the capital. Seven bridges provide crossings over the Danube, and from north to south are: the Árpád Bridge (built in 1950 at the north of Margaret Island); the Margaret Bridge (built in 1901, destroyed during the war by an explosion and then rebuilt in 1948); the Chain Bridge (built in 1849, destroyed during World War II and then rebuilt in 1949); the Elisabeth Bridge (completed in 1903 and dedicated to the murdered Queen Elisabeth, it was destroyed by the Germans during the war and replaced with a new bridge in 1964); the Liberty Bridge (opened in 1896 and rebuilt in 1989 in Art Nouveau style); the Petőfi Bridge (completed in 1937, destroyed during the war and rebuilt in 1952); the Rákóczi Bridge (completed in 1995). Most remarkable for their beauty are the Margaret Bridge, the Chain Bridge and the Liberty Bridge. The world’s largest panorama photograph was created in (and of) Budapest in 2010.[183]

Tourists visiting Budapest can receive free maps and information from the nonprofit Budapest Festival and Tourism Center at its info-points.[184] The info centers also offer the Budapest Card which allows free public transit and discounts for several museums, restaurants and other places of interest. Cards are available for 24-, 48- or 72-hour durations.[185] The city is also well known for its ruin bars both day and night.[186]

Squares[edit]