Coordinates: 61°N 8°E / 61°N 8°E

|

Kingdom of Norway Other official names

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Ja, vi elsker dette landet (English: «Yes, we love this country») Royal anthem: Kongesangen |

|

|

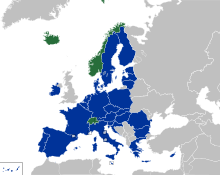

Location of the Kingdom of Norway (green) in Europe (green and dark grey) |

|

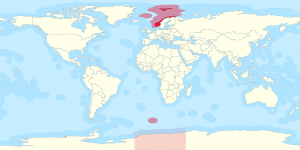

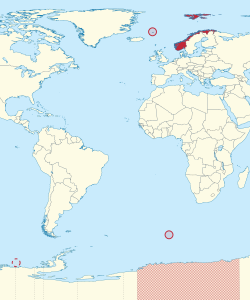

Location of the Kingdom of Norway and its integral overseas territories and dependencies: Svalbard, Jan Mayen, Bouvet Island, Peter I Island, and Queen Maud Land |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Oslo 59°56′N 10°41′E / 59.933°N 10.683°E |

| Official languages |

|

| Recognised national languages |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2021)[3][4][5][6][7] |

|

| Religion

(2021)[9][10] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Norwegian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

|

• Monarch |

Harald V |

|

• Prime Minister |

Jonas Gahr Støre |

|

• President of the Storting |

Masud Gharahkhani |

|

• Chief Justice |

Toril Marie Øie |

| Legislature | Storting |

| History | |

|

• State established prior unification |

872 |

|

• Old Kingdom of Norway (Peak extent) |

1263 |

|

• Kalmar Union |

1397 |

|

• Denmark–Norway |

1524 |

|

• Re-established state[11] |

25 February 1814 |

|

• Constitution |

17 May 1814 |

|

• Union between Sweden and Norway |

4 November 1814 |

|

• Dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden |

7 June 1905 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

385,207 km2 (148,729 sq mi)[12] (61stb) |

|

• Water (%) |

5.32 (2015)[13] |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

|

|

• Density |

14.0/km2 (36.3/sq mi) (213th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 2nd |

| Currency | Norwegian krone (NOK) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +47 |

| ISO 3166 code | NO |

| Internet TLD | .nod |

|

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway,[a] is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of Norway.[note 5] Bouvet Island, located in the Subantarctic, is a dependency of Norway; it also lays claims to the Antarctic territories of Peter I Island and Queen Maud Land. The capital and largest city in Norway is Oslo.

Norway has a total area of 385,207 square kilometres (148,729 sq mi)[12] and had a population of 5,425,270 in January 2022.[14] The country shares a long eastern border with Sweden at a length of 1,619 km (1,006 mi). It is bordered by Finland and Russia to the northeast and the Skagerrak strait to the south, on the other side of which are Denmark and the United Kingdom. Norway has an extensive coastline, facing the North Atlantic Ocean and the Barents Sea. The maritime influence dominates Norway’s climate, with mild lowland temperatures on the sea coasts; the interior, while colder, is also significantly milder than areas elsewhere in the world on such northerly latitudes. Even during polar night in the north, temperatures above freezing are commonplace on the coastline. The maritime influence brings high rainfall and snowfall to some areas of the country.

Harald V of the House of Glücksburg is the current King of Norway. Jonas Gahr Støre has been prime minister since 2021, replacing Erna Solberg. As a unitary sovereign state with a constitutional monarchy, Norway divides state power between the parliament, the cabinet and the supreme court, as determined by the 1814 constitution. The kingdom was established in 872 as a merger of many petty kingdoms and has existed continuously for 1,151 years. From 1537 to 1814, Norway was a part of the Kingdom of Denmark–Norway, and, from 1814 to 1905, it was in a personal union with the Kingdom of Sweden. Norway was neutral during the First World War, and also in World War II until April 1940 when the country was invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany until the end of the war.

Norway has both administrative and political subdivisions on two levels: counties and municipalities. The Sámi people have a certain amount of self-determination and influence over traditional territories through the Sámi Parliament and the Finnmark Act. Norway maintains close ties with both the European Union and the United States. Norway is also a founding member of the United Nations, NATO, the European Free Trade Association, the Council of Europe, the Antarctic Treaty, and the Nordic Council; a member of the European Economic Area, the WTO, and the OECD; and a part of the Schengen Area. In addition, the Norwegian languages share mutual intelligibility with Danish and Swedish.

Norway maintains the Nordic welfare model with universal health care and a comprehensive social security system, and its values are rooted in egalitarian ideals.[21] The Norwegian state has large ownership positions in key industrial sectors, having extensive reserves of petroleum, natural gas, minerals, lumber, seafood, and fresh water. The petroleum industry accounts for around a quarter of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).[22] On a per-capita basis, Norway is the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas outside of the Middle East.[23][24]

The country has the fourth-highest per-capita income in the world on the World Bank and IMF lists.[25] On the CIA’s GDP (PPP) per capita list (2015 estimate) which includes autonomous territories and regions, Norway ranks as number eleven.[26] It has the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, with a value of US$1 trillion.[27] Norway has the second highest Human Development Index ranking in the world, previously holding the top position between 2001 and 2006, and between 2009 and 2019;[28] it also has the second highest inequality-adjusted ranking per 2021.[29] Norway ranked first on the World Happiness Report for 2017[30] and currently ranks first on the OECD Better Life Index, the Index of Public Integrity, the Freedom Index,[31] and the Democracy Index.[32] Norway also has one of the lowest crime rates in the world.[33]

Although the majority of Norway’s population is ethnic Norwegian, in the 21st century immigration has accounted for more than half of population growth; in 2021, the five largest minority groups in the country were the descendants of Polish, Lithuanian, Somali, Pakistani, and Swedish immigrants.[7]

Etymology

Opening of Ohthere’s Old English account, translated: «Ohthere told his lord Ælfrede king that he lived northmost of all Norwegians…»

Norway has two official names: Norge in Bokmål and Noreg in Nynorsk. The English name Norway comes from the Old English word Norþweg mentioned in 880, meaning «northern way» or «way leading to the north», which is how the Anglo-Saxons referred to the coastline of Atlantic Norway[34][35][36] similar to leading theory about the origin of the Norwegian language name.[37] The Anglo-Saxons of Britain also referred to the kingdom of Norway in 880 as Norðmanna land.[34][35]

There is some disagreement about whether the native name of Norway originally had the same etymology as the English form. According to the traditional dominant view, the first component was originally norðr, a cognate of English north, so the full name was Norðr vegr, «the way northwards», referring to the sailing route along the Norwegian coast, and contrasting with suðrvegar «southern way» (from Old Norse suðr) for (Germany), and austrvegr «eastern way» (from austr) for the Baltic. In the translation of Orosius for Alfred, the name is Norðweg, while in younger Old English sources the ð is gone.[38] In the tenth century many Norsemen settled in Northern France, according to the sagas, in the area that was later called Normandy from norðmann (Norseman or Scandinavian[39][40]), although not a Norwegian possession.[41] In France normanni or northmanni referred to people of Norway, Sweden or Denmark.[42] Until around 1800, inhabitants of Western Norway were referred to as nordmenn (northmen) while inhabitants of Eastern Norway were referred to as austmenn (eastmen).[43]

According to another theory, the first component was a word nór, meaning «narrow» (Old English nearu), referring to the inner-archipelago sailing route through the land («narrow way»). The interpretation as «northern», as reflected in the English and Latin forms of the name, would then have been due to later folk etymology. This latter view originated with philologist Niels Halvorsen Trønnes in 1847; since 2016 it is also advocated by language student and activist Klaus Johan Myrvoll and was adopted by philology professor Michael Schulte.[34][35] The form Nore is still used in placenames such as the village of Nore and lake Norefjorden in Buskerud county, and still has the same meaning.[34][35] Among other arguments in favour of the theory, it is pointed out that the word has a long vowel in Skaldic poetry and is not attested with <ð> in any native Norse texts or inscriptions (the earliest runic attestations have the spellings nuruiak and nuriki). This resurrected theory has received some pushback by other scholars on various grounds, e. g. the uncontroversial presence of the element norðr in the ethnonym norðrmaðr «Norseman, Norwegian person» (modern Norwegian nordmann), and the adjective norrǿnn «northern, Norse, Norwegian», as well as the very early attestations of the Latin and Anglo-Saxon forms with <th>.[38][35]

In a Latin manuscript of 840, the name Northuagia is mentioned.[36] King Alfred’s edition of the Orosius World History (dated 880), uses the term Norðweg.[36] A French chronicle of c. 900 uses the names Northwegia and Norwegia.[44] When Ohthere of Hålogaland visited King Alfred the Great in England in the end of the ninth century, the land was called Norðwegr (lit. «Northway») and norðmanna land (lit. «Northmen’s land»).[44] According to Ohthere, Norðmanna lived along the Atlantic coast, the Danes around Skagerrak og Kattegat, while the Sámi people (the «Fins») had a nomadic lifestyle in the wide interior.[45][46] Ohthere told Alfred that he was «the most northern of all Norwegians», presumably at Senja island or closer to Tromsø. He also said that beyond the wide wilderness in Norway’s southern part was the land of the Swedes, «Svealand».[47][48]

The adjective Norwegian, recorded from c. 1600, is derived from the latinisation of the name as Norwegia; in the adjective Norwegian, the Old English spelling ‘-weg’ has survived.[49]

After Norway had become Christian, Noregr and Noregi had become the most common forms, but during the 15th century, the newer forms Noreg(h) and Norg(h)e, found in medieval Icelandic manuscripts, took over and have survived until the modern day.[citation needed]

History

Prehistory

The first inhabitants were the Ahrensburg culture (11th to 10th millennia BC), which was a late Upper Paleolithic culture during the Younger Dryas, the last period of cold at the end of the Weichselian glaciation. The culture is named after the village of Ahrensburg, 25 km (15.53 mi) northeast of Hamburg in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, where wooden arrow shafts and clubs have been excavated.[50] The earliest traces of human occupation in Norway are found along the coast, where the huge ice shelf of the last ice age first melted between 11,000 and 8,000 BC. The oldest finds are stone tools dating from 9,500 to 6,000 BC, discovered in Finnmark (Komsa culture) in the north and Rogaland (Fosna culture) in the southwest. However, theories about two altogether different cultures (the Komsa culture north of the Arctic Circle being one and the Fosna culture from Trøndelag to Oslofjord being the other) were rendered obsolete in the 1970s.[51]

More recent finds along the entire coast revealed to archaeologists that the difference between the two can simply be ascribed to different types of tools and not to different cultures. Coastal fauna provided a means of livelihood for fishermen and hunters, who may have made their way along the southern coast about 10,000 BC when the interior was still covered with ice. It is now thought that these so-called «Arctic» peoples came from the south and followed the coast northward considerably later.

In the southern part of the country are dwelling sites dating from about 5,000 BC. Finds from these sites give a clearer idea of the life of the hunting and fishing peoples. The implements vary in shape and mostly are made of different kinds of stone; those of later periods are more skilfully made. Rock carvings (i.e. petroglyphs) have been found, usually near hunting and fishing grounds. They represent game such as deer, reindeer, elk, bears, birds, seals, whales, and fish (especially salmon and halibut), all of which were vital to the way of life of the coastal peoples. The rock carvings at Alta in Finnmark, the largest in Scandinavia, were made at sea level from 4,200 to 500 BC and mark the progression of the land as the sea rose after the last ice age ended.

Bronze Age

Between 3000 and 2500 BC, new settlers (Corded Ware culture) arrived in eastern Norway. They were Indo-European farmers who grew grain and kept cows and sheep. The hunting-fishing population of the west coast was also gradually replaced by farmers, though hunting and fishing remained useful secondary means of livelihood.

From about 1500 BC, bronze was gradually introduced, but the use of stone implements continued; Norway had few riches to barter for bronze goods, and the few finds consist mostly of elaborate weapons and brooches that only chieftains could afford. Huge burial cairns built close to the sea as far north as Harstad and also inland in the south are characteristic of this period. The motifs of the rock carvings differ slightly from those typical of the Stone Age. Representations of the Sun, animals, trees, weapons, ships, and people are all strongly stylised.

Thousands of rock carvings from this period depict ships, and the large stone burial monuments known as stone ships, suggest that ships and seafaring played an important role in the culture at large. The depicted ships most likely represent sewn plank built canoes used for warfare, fishing and trade. These ship types may have their origin as far back as the neolithic period and they continue into the Pre-Roman Iron Age, as exemplified by the Hjortspring boat.[52]

Iron Age

Little has been found dating from the early Iron Age (the last 500 years BC). The dead were cremated, and their graves contain few burial goods. During the first four centuries AD, the people of Norway were in contact with Roman-occupied Gaul. About 70 Roman bronze cauldrons, often used as burial urns, have been found. Contact with the civilised countries farther south brought a knowledge of runes; the oldest known Norwegian runic inscription dates from the third century. At this time, the amount of settled area in the country increased, a development that can be traced by coordinated studies of topography, archaeology, and place-names. The oldest root names, such as nes, vik, and bø («cape,» «bay,» and «farm»), are of great antiquity, dating perhaps from the Bronze Age, whereas the earliest of the groups of compound names with the suffixes vin («meadow») or heim («settlement»), as in Bjǫrgvin (Bergen) or Sǿheim (Seim), usually date from the first century AD.

Archaeologists first made the decision to divide the Iron Age of Northern Europe into distinct pre-Roman and Roman Iron Ages after Emil Vedel unearthed a number of Iron Age artefacts in 1866 on the island of Bornholm.[53] They did not exhibit the same permeating Roman influence seen in most other artefacts from the early centuries AD, indicating that parts of northern Europe had not yet come into contact with the Romans at the beginning of the Iron Age.

Migration period

The destruction of the Western Roman Empire by the Germanic peoples in the fifth century is characterised by rich finds, including tribal chiefs’ graves containing magnificent weapons and gold objects.[citation needed] Hill forts were built on precipitous rocks for defence. Excavation has revealed stone foundations of farmhouses 18 to 27 metres (59 to 89 ft) long—one even 46 metres (151 feet) long—the roofs of which were supported on wooden posts. These houses were family homesteads where several generations lived together, with people and cattle under one roof.[citation needed]

These states were based on either clans or tribes (e.g., the Horder of Hordaland in western Norway). By the ninth century, each of these small states had things (local or regional assemblies) for negotiating and settling disputes. The thing meeting places, each eventually with a hörgr (open-air sanctuary) or a heathen hof (temple; literally «hill»), were usually situated on the oldest and best farms, which belonged to the chieftains and wealthiest farmers. The regional things united to form even larger units: assemblies of deputy yeomen from several regions. In this way, the lagting (assemblies for negotiations and lawmaking) developed. The Gulating had its meeting place by Sognefjord and may have been the centre of an aristocratic confederation[citation needed] along the western fjords and islands called the Gulatingslag. The Frostating was the assembly for the leaders in the Trondheimsfjord area; the Earls of Lade, near Trondheim, seem to have enlarged the Frostatingslag by adding the coastland from Romsdalsfjord to Lofoten.[citation needed]

Viking Age

From the eighth to the tenth century, the wider Scandinavian region was the source of Vikings. The looting of the monastery at Lindisfarne in Northeast England in 793 by Norse people has long been regarded as the event which marked the beginning of the Viking Age.[54] This age was characterised by expansion and emigration by Viking seafarers. They colonised, raided, and traded in all parts of Europe. Norwegian Viking explorers discovered Iceland by accident in the ninth century when heading for the Faroe Islands, and eventually came across Vinland, known today as Newfoundland, in Canada. The Vikings from Norway were most active in the northern and western British Isles and eastern North America isles.[55]

According to tradition, Harald Fairhair unified them into one in 872 after the Battle of Hafrsfjord in Stavanger, thus becoming the first king of a united Norway.[56] Harald’s realm was mainly a South Norwegian coastal state. Fairhair ruled with a strong hand and according to the sagas, many Norwegians left the country to live in Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and parts of Britain and Ireland. The modern-day Irish cities of Dublin, Limerick and Waterford were founded by Norwegian settlers.[57]

Norse traditions were replaced slowly by Christian ones in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. One of the most important sources for the history of the 11th century Vikings is the treaty between the Icelanders and Olaf Haraldsson, king of Norway circa 1015 to 1028.[58] This is largely attributed to the missionary kings Olav Tryggvasson and St. Olav. Haakon the Good was Norway’s first Christian king, in the mid-10th century, though his attempt to introduce the religion was rejected. Born sometime in between 963 and 969, Olav Tryggvasson set off raiding in England with 390 ships. He attacked London during this raiding. Arriving back in Norway in 995, Olav landed in Moster. There he built a church which became the first Christian church ever built in Norway. From Moster, Olav sailed north to Trondheim where he was proclaimed King of Norway by the Eyrathing in 995.[59]

Feudalism never really developed in Norway or Sweden, as it did in the rest of Europe. However, the administration of government took on a very conservative feudal character. The Hanseatic League forced the royalty to cede to them greater and greater concessions over foreign trade and the economy. The League had this hold over the royalty because of the loans the Hansa had made to the royalty and the large debt the kings were carrying. The League’s monopolistic control over the economy of Norway put pressure on all classes, especially the peasantry, to the degree that no real burgher class existed in Norway.[60]

Civil war and peak of power

From the 1040s to 1130, the country was at peace.[61] In 1130, the civil war era broke out on the basis of unclear succession laws, which allowed all the king’s sons to rule jointly. For periods there could be peace, before a lesser son allied himself with a chieftain and started a new conflict. The Archdiocese of Nidaros was created in 1152 and attempted to control the appointment of kings.[62] The church inevitably had to take sides in the conflicts, with the civil wars also becoming an issue regarding the church’s influence of the king. The wars ended in 1217 with the appointment of Håkon Håkonsson, who introduced clear law of succession.[63]

From 1000 to 1300, the population increased from 150,000 to 400,000, resulting both in more land being cleared and the subdivision of farms. While in the Viking Age all farmers owned their own land, by 1300, seventy percent of the land was owned by the king, the church, or the aristocracy. This was a gradual process which took place because of farmers borrowing money in poor times and not being able to repay. However, tenants always remained free men and the large distances and often scattered ownership meant that they enjoyed much more freedom than continental serfs. In the 13th century, about twenty percent of a farmer’s yield went to the king, church and landowners.[64]

The 14th century is described as Norway’s Golden Age, with peace and increase in trade, especially with the British Islands, although Germany became increasingly important towards the end of the century. Throughout the High Middle Ages, the king established Norway as a sovereign state with a central administration and local representatives.[65]

In 1349, the Black Death spread to Norway and had within a year killed a third of the population. Later plagues reduced the population to half the starting point by 1400. Many communities were entirely wiped out, resulting in an abundance of land, allowing farmers to switch to more animal husbandry. The reduction in taxes weakened the king’s position,[66] and many aristocrats lost the basis for their surplus, reducing some to mere farmers. High tithes to church made it increasingly powerful and the archbishop became a member of the Council of State.[67]

The Hanseatic League took control over Norwegian trade during the 14th century and established a trading centre in Bergen. In 1380, Olaf Haakonsson inherited both the Norwegian and Danish thrones, creating a union between the two countries.[67] In 1397, under Margaret I, the Kalmar Union was created between the three Scandinavian countries. She waged war against the Germans, resulting in a trade blockade and higher taxation on Norwegian goods, which resulted in a rebellion. However, the Norwegian Council of State was too weak to pull out of the union.[68]

Margaret pursued a centralising policy which inevitably favoured Denmark, because it had a greater population than Norway and Sweden combined.[69] Margaret also granted trade privileges to the Hanseatic merchants of Lübeck in Bergen in return for recognition of her right to rule, and these hurt the Norwegian economy. The Hanseatic merchants formed a state within a state in Bergen for generations.[70] Even worse were the pirates, the «Victual Brothers», who launched three devastating raids on the port (the last in 1427).[71]

Norway slipped ever more to the background under the Oldenburg dynasty (established 1448). There was one revolt under Knut Alvsson in 1502.[72] Norwegians had some affection for King Christian II, who resided in the country for several years. Norway took no part in the events which led to Swedish independence from Denmark in the 1520s.[73]

Kalmar Union

Upon the death of Haakon V (King of Norway) in 1319, Magnus Erikson, at just three years old, inherited the throne as King Magnus VII of Norway. At the same time, a movement to make Magnus King of Sweden proved successful, and both the kings of Sweden and of Denmark were elected to the throne by their respective nobles, Thus, with his election to the throne of Sweden, both Sweden and Norway were united under King Magnus VII.[74]

In 1349, the Black Death radically altered Norway, killing between 50% and 60% of its population[75] and leaving it in a period of social and economic decline.[76] The plague left Norway very poor. Although the death rate was comparable with the rest of Europe, economic recovery took much longer because of the small, scattered population.[76] Even before the plague, the population was only about 500,000.[77] After the plague, many farms lay idle while the population slowly increased.[76] However, the few surviving farms’ tenants found their bargaining positions with their landlords greatly strengthened.[76]

King Magnus VII ruled Norway until 1350, when his son, Haakon, was placed on the throne as Haakon VI.[78] In 1363, Haakon VI married Margaret, the daughter of King Valdemar IV of Denmark.[76] Upon the death of Haakon VI, in 1379, his son, Olaf IV, was only 10 years old.[76] Olaf had already been elected to the throne of Denmark on 3 May 1376.[76] Thus, upon Olaf’s accession to the throne of Norway, Denmark and Norway entered personal union.[79] Olaf’s mother and Haakon’s widow, Queen Margaret, managed the foreign affairs of Denmark and Norway during the minority of Olaf IV.[76]

Margaret was working toward a union of Sweden with Denmark and Norway by having Olaf elected to the Swedish throne. She was on the verge of achieving this goal when Olaf IV suddenly died.[76] However, Denmark made Margaret temporary ruler upon the death of Olaf. On 2 February 1388, Norway followed suit and crowned Margaret.[76] Queen Margaret knew that her power would be more secure if she were able to find a king to rule in her place. She settled on Eric of Pomerania, grandson of her sister. Thus at an all-Scandinavian meeting held at Kalmar, Erik of Pomerania was crowned king of all three Scandinavian countries. Thus, royal politics resulted in personal unions between the Nordic countries, eventually bringing the thrones of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden under the control of Queen Margaret when the country entered into the Kalmar Union.

Union with Denmark

After Sweden broke out of the Kalmar Union in 1521, Norway tried to follow suit,[citation needed] but the subsequent rebellion was defeated, and Norway remained in a union with Denmark until 1814, a total of 434 years. During the national romanticism of the 19th century, this period was by some referred to as the «400-Year Night», since all of the kingdom’s royal, intellectual, and administrative power was centred in Copenhagen in Denmark. In fact, it was a period of great prosperity and progress for Norway, especially in terms of shipping and foreign trade, and it also secured the country’s revival from the demographic catastrophe it suffered in the Black Death. Based on the respective natural resources, Denmark–Norway was in fact a very good match since Denmark supported Norway’s needs for grain and food supplies, and Norway supplied Denmark with timber, metal, and fish.

With the introduction of Protestantism in 1536, the archbishopric in Trondheim was dissolved, and Norway lost its independence, and effectually became a colony of Denmark. The Church’s incomes and possessions were instead redirected to the court in Copenhagen. Norway lost the steady stream of pilgrims to the relics of St. Olav at the Nidaros shrine, and with them, much of the contact with cultural and economic life in the rest of Europe.

Eventually restored as a kingdom (albeit in legislative union with Denmark) in 1661, Norway saw its land area decrease in the 17th century with the loss of the provinces Båhuslen, Jemtland, and Herjedalen to Sweden, as the result of a number of disastrous wars with Sweden. In the north, however, its territory was increased by the acquisition of the northern provinces of Troms and Finnmark, at the expense of Sweden and Russia.

The famine of 1695–1696 killed roughly 10% of Norway’s population.[80] The harvest failed in Scandinavia at least nine times between 1740 and 1800, with great loss of life.[81]

Union with Sweden

After Denmark–Norway was attacked by the United Kingdom at the 1807 Battle of Copenhagen, it entered into an alliance with Napoleon, with the war leading to dire conditions and mass starvation in 1812. As the Danish kingdom found itself on the losing side in 1814, it was forced, under terms of the Treaty of Kiel, to cede Norway to the king of Sweden, while the old Norwegian provinces of Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands remained with the Danish crown.[82] Norway took this opportunity to declare independence, adopted a constitution based on American and French models, and elected the Crown Prince of Denmark and Norway, Christian Frederick, as king on 17 May 1814. This is the famous Syttende mai (Seventeenth of May) holiday celebrated by Norwegians and Norwegian-Americans alike. Syttende mai is also called Norwegian Constitution Day.

Norwegian opposition to the great powers’ decision to link Norway with Sweden caused the Norwegian–Swedish War to break out as Sweden tried to subdue Norway by military means. As Sweden’s military was not strong enough to defeat the Norwegian forces outright, and Norway’s treasury was not large enough to support a protracted war, and as British and Russian navies blockaded the Norwegian coast,[83] the belligerents were forced to negotiate the Convention of Moss. According to the terms of the convention, Christian Frederik abdicated the Norwegian throne and authorised the Parliament of Norway to make the necessary constitutional amendments to allow for the personal union that Norway was forced to accept. On 4 November 1814, the Parliament (Storting) elected Charles XIII of Sweden as king of Norway, thereby establishing the union with Sweden.[84] Under this arrangement, Norway kept its liberal constitution and its own independent institutions, though it shared a common monarch and common foreign policy with Sweden. Following the recession caused by the Napoleonic Wars, economic development of Norway remained slow until economic growth began around 1830.[85]

Harvesting of oats in Jølster, c. 1890

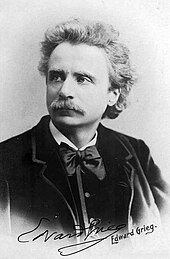

This period also saw the rise of the Norwegian romantic nationalism, as Norwegians sought to define and express a distinct national character. The movement covered all branches of culture, including literature (Henrik Wergeland [1808–1845], Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson [1832–1910], Peter Christen Asbjørnsen [1812–1845], Jørgen Moe [1813–1882]), painting (Hans Gude [1825–1903], Adolph Tidemand [1814–1876]), music (Edvard Grieg [1843–1907]), and even language policy, where attempts to define a native written language for Norway led to today’s two official written forms for Norwegian: Bokmål and Nynorsk.

King Charles III John, who came to the throne of Norway and Sweden in 1818, was the second king following Norway’s break from Denmark and the union with Sweden. Charles John was a complex man whose long reign extended to 1844. He protected the constitution and liberties of Norway and Sweden during the age of Metternich.[neutrality is disputed] As such, he was regarded as a liberal monarch for that age. However, he was ruthless in his use of paid informers, the secret police and restrictions on the freedom of the press to put down public movements for reform—especially the Norwegian national independence movement.[86]

The Romantic Era that followed the reign of King Charles III John brought some significant social and political reforms. In 1854, women won the right to inherit property in their own right, just like men. In 1863, the last trace of keeping unmarried women in the status of minors was removed. Furthermore, women were then eligible for different occupations, particularly the common school teacher.[87] By mid-century, Norway’s democracy was limited; voting was limited to officials, property owners, leaseholders and burghers of incorporated towns.[88]

A Sámi family in Norway, c. 1900

Still, Norway remained a conservative society. Life in Norway (especially economic life) was «dominated by the aristocracy of professional men who filled most of the important posts in the central government».[89] There was no strong bourgeosie class in Norway to demand a breakdown of this aristocratic control of the economy.[90] Thus, even while revolution swept over most of the countries of Europe in 1848, Norway was largely unaffected by revolts that year.[90]

Marcus Thrane was a Utopian socialist. He made his appeal to the labouring classes urging a change of social structure «from below upwards.» In 1848, he organised a labour society in Drammen. In just a few months, this society had a membership of 500 and was publishing its own newspaper. Within two years, 300 societies had been organised all over Norway, with a total membership of 20,000 persons. The membership was drawn from the lower classes of both urban and rural areas; for the first time these two groups felt they had a common cause.[91] In the end, the revolt was easily crushed; Thrane was captured and in 1855, after four years in jail, was sentenced to three additional years for crimes against the safety of the state. Upon his release, Marcus Thrane attempted unsuccessfully to revitalise his movement, but after the death of his wife, he migrated to the United States.[92]

In 1898, all men were granted universal suffrage, followed by all women in 1913.

Dissolution of the union and the first World War

Christian Michelsen, a shipping magnate and statesman, and Prime Minister of Norway from 1905 to 1907, played a central role in the peaceful separation of Norway from Sweden on 7 June 1905. A national referendum confirmed the people’s preference for a monarchy over a republic. However, no Norwegian could legitimately claim the throne, since none of Norway’s noble families could claim descent from medieval royalty. In European tradition, royal or «blue» blood is a precondition for laying claim to the throne.

The government then offered the throne of Norway to Prince Carl of Denmark, a prince of the Dano-German royal house of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg and a distant relative of several of Norway’s medieval kings. After centuries of close ties between Norway and Denmark, a prince from the latter was the obvious choice for a European prince who could best relate to the Norwegian people. Following the plebiscite, he was unanimously elected king by the Norwegian Parliament, the first king of a fully independent Norway in 508 years (1397: Kalmar Union); he took the name Haakon VII. In 1905, the country welcomed the prince from neighbouring Denmark, his wife Maud of Wales and their young son to re-establish Norway’s royal house.

Throughout the First World War, Norway remained neutral; however, diplomatic pressure from the British government meant that it heavily favoured the Allies during the war. During the war, Norway exported fish to both Germany and Britain, until an ultimatum from the British government and anti-German sentiments as a result of German submarines targeting Norwegian merchantmen led to a termination of trade with Germany. 436 Norwegian merchantmen were sunk by the Kaiserliche Marine during the war, with 1,150 Norwegian sailors losing their lives.[93][disputed – discuss]

Second World War

Norway once more proclaimed its neutrality during the Second World War, but this time, it was invaded by German forces on 9 April 1940. Although Norway was unprepared for the German surprise attack (see: Battle of Drøbak Sound, Norwegian Campaign, and Invasion of Norway), military and naval resistance lasted for two months. Norwegian armed forces in the north launched an offensive against the German forces in the Battles of Narvik, until they were forced to surrender on 10 June after losing British support which had been diverted to France during the German invasion of France.

Bombing of Kristiansund. The German invasion resulted in 24 towns being bombed in the spring of 1940.

King Haakon and the Norwegian government escaped to Rotherhithe in London. Throughout the war they sent inspirational radio speeches and supported clandestine military actions in Norway against the Germans. On the day of the invasion, the leader of the small National-Socialist party Nasjonal Samling, Vidkun Quisling, tried to seize power, but was forced by the German occupiers to step aside. Real power was wielded by the leader of the German occupation authority, Reichskommissar Josef Terboven. Quisling, as minister president, later formed a collaborationist government under German control. Up to 15,000 Norwegians volunteered to fight in German units, including the Waffen-SS.[94]

The fraction of the Norwegian population that supported Germany was traditionally smaller than in Sweden, but greater than is generally appreciated today.[citation needed] It included a number of prominent personalities such as the Nobel-prize winning novelist Knut Hamsun. The concept of a «Germanic Union» of member states fit well into their thoroughly nationalist-patriotic ideology.

Norwegian fighter pilots in the United Kingdom during World War II

Many Norwegians and persons of Norwegian descent joined the Allied forces as well as the Free Norwegian Forces. In June 1940, a small group had left Norway following their king to Britain. This group included 13 ships, five aircraft, and 500 men from the Royal Norwegian Navy. By the end of the war, the force had grown to 58 ships and 7,500 men in service in the Royal Norwegian Navy, 5 squadrons of aircraft (including Spitfires, Sunderland flying boats and Mosquitos) in the newly formed Norwegian Air Force, and land forces including the Norwegian Independent Company 1 and 5 Troop as well as No. 10 Commandos.[citation needed]

During the five years of German occupation, Norwegians built a resistance movement which fought the German occupation forces with both civil disobedience and armed resistance including the destruction of Norsk Hydro’s heavy water plant and stockpile of heavy water at Vemork, which crippled the German nuclear programme (see: Norwegian heavy water sabotage). More important to the Allied war effort, however, was the role of the Norwegian Merchant Marine. At the time of the invasion, Norway had the fourth-largest merchant marine fleet in the world. It was led by the Norwegian shipping company Nortraship under the Allies throughout the war and took part in every war operation from the evacuation of Dunkirk to the Normandy landings. Every December Norway gives a Christmas tree to the United Kingdom as thanks for the British assistance during the Second World War. A ceremony takes place to erect the tree in London’s Trafalgar Square.[95]

Svalbard was not occupied by German troops, but Germany secretly established a meteorological station there in 1944; the crew was stranded after the general capitulation in May 1945 and were rescued by a Norwegian seal hunter on 4 September. They were the last German soldiers to surrender in WW2.[96]

Post-World War II history

From 1945 to 1962, the Labour Party held an absolute majority in the parliament. The government, led by prime minister Einar Gerhardsen, embarked on a programme inspired by Keynesian economics, emphasising state financed industrialisation and co-operation between trade unions and employers’ organisations. Many measures of state control of the economy imposed during the war were continued, although the rationing of dairy products was lifted in 1949, while price controls and rationing of housing and cars continued until 1960.

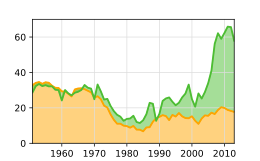

Since the 1970s oil production has helped to expand the Norwegian economy and finance the Norwegian state. (Statfjord oil field)

The wartime alliance with the United Kingdom and the United States was continued in the post-war years. Although pursuing the goal of a socialist economy, the Labour Party distanced itself from the Communists, especially after the Communists’ seizure of power in Czechoslovakia in 1948, and strengthened its foreign policy and defence policy ties with the US. Norway received Marshall Plan aid from the United States starting in 1947, joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) one year later, and became a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949.

The first oil was discovered at the small Balder field in 1967, but production only began in 1999.[97] In 1969, the Phillips Petroleum Company discovered petroleum resources at the Ekofisk field west of Norway. In 1973, the Norwegian government founded the State oil company, Statoil. Oil production did not provide net income until the early 1980s because of the large capital investment that was required to establish the country’s petroleum industry. Around 1975, both the proportion and absolute number of workers in industry peaked. Since then labour-intensive industries and services like factory mass production and shipping have largely been outsourced.

Norway was a founding member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Norway was twice invited to join the European Union, but ultimately declined to join after referendums that failed by narrow margins in 1972 and 1994.[98]

Town Hall Square in Oslo filled with people with roses mourning the victims of the Utøya massacre of 22 July 2011

In 1981, a Conservative Party government led by Kåre Willoch replaced the Labour Party with a policy of stimulating the stagflated economy with tax cuts, economic liberalisation, deregulation of markets, and measures to curb record-high inflation (13.6% in 1981).

Norway’s first female prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland of the Labour Party continued many of the reforms of her Conservative predecessor, while backing traditional Labour concerns such as social security, high taxes, the industrialisation of nature, and feminism. By the late 1990s, Norway had paid off its foreign debt and had started accumulating a sovereign wealth fund. Since the 1990s, a divisive question in politics has been how much of the income from petroleum production the government should spend, and how much it should save.

In 2011, Norway suffered two terrorist attacks on the same day conducted by Anders Behring Breivik which struck the government quarter in Oslo and a summer camp of the Labour party’s youth movement at Utøya island, resulting in 77 deaths and 319 wounded.[99]

Jens Stoltenberg, leader of the Labour Party, led Norway as Prime Minister for eight years from 2005 to 2013.[100] The 2013 Norwegian parliamentary election brought a more conservative government to power, with the Conservative Party and the Progress Party winning 43% of the electorate’s votes.[101] In the Norwegian parliamentary election 2017 the centre-right government of Prime Minister Erna Solberg won re-election.[102] The 2021 Norwegian parliamentary election saw a big win for the left-wing opposition in an election fought on climate change, inequality, and oil.[103] Labour leader Jonas Gahr Støre was sworn in as new prime minister, in a centre-left minority government comprising 10 women and nine men.[104]

Geography

A satellite image of continental Norway in winter

Norway’s core territory comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula; the remote island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard are also part of the Kingdom of Norway.[note 5] The Antarctic Peter I Island and the sub-Antarctic Bouvet Island are dependent territories and thus not considered part of the Kingdom. Norway also lays claim to a section of Antarctica known as Queen Maud Land.[105] From the Middle Ages to 1814 Norway was part of the Danish kingdom. Norwegian possessions in the North Atlantic, Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Iceland, remained Danish when Norway was passed to Sweden at the Treaty of Kiel.[106] Norway also comprised Bohuslän until 1658, Jämtland and Härjedalen until 1645,[105] Shetland and Orkney until 1468,[107] and the Hebrides and Isle of Man until the Treaty of Perth in 1266.[108]

Norway comprises the western and northernmost part of Scandinavia in Northern Europe.[109] Norway lies between latitudes 57° and 81° N, and longitudes 4° and 32° E. Norway is the northernmost of the Nordic countries and if Svalbard is included also the easternmost.[110] Vardø at 31° 10′ 07″ east of Greenwich lies further east than St. Petersburg and Istanbul.[111] Norway includes the northernmost point on the European mainland.[112] The rugged coastline is broken by huge fjords and thousands of islands. The coastal baseline is 2,532 kilometres (1,573 mi). The coastline of the mainland including fjords stretches 28,953 kilometres (17,991 mi), when islands are included the coastline has been estimated to 100,915 kilometres (62,706 mi).[113] Norway shares a 1,619-kilometre (1,006 mi) land border with Sweden, 727 kilometres (452 mi) with Finland, and 196 kilometres (122 mi) with Russia to the east. To the north, west and south, Norway is bordered by the Barents Sea, the Norwegian Sea, the North Sea, and Skagerrak.[114] The Scandinavian Mountains form much of the border with Sweden.

At 385,207 square kilometres (148,729 sq mi) (including Svalbard and Jan Mayen) (and 323,808 square kilometres (125,023 sq mi) without),[12] much of the country is dominated by mountainous or high terrain, with a great variety of natural features caused by prehistoric glaciers and varied topography. The most noticeable of these are the fjords: deep grooves cut into the land flooded by the sea following the end of the Ice Age. Sognefjorden is the world’s second deepest fjord, and the world’s longest at 204 kilometres (127 mi). Hornindalsvatnet is the deepest lake in all Europe.[115] Norway has about 400,000 lakes.[116][117] There are 239,057 registered islands.[109] Permafrost can be found all year in the higher mountain areas and in the interior of Finnmark county. Numerous glaciers are found in Norway.

The land is mostly made of hard granite and gneiss rock, but slate, sandstone, and limestone are also common, and the lowest elevations contain marine deposits. Because of the Gulf Stream and prevailing westerlies, Norway experiences higher temperatures and more precipitation than expected at such northern latitudes, especially along the coast. The mainland experiences four distinct seasons, with colder winters and less precipitation inland. The northernmost part has a mostly maritime Subarctic climate, while Svalbard has an Arctic tundra climate.

Because of the large latitudinal range of the country and the varied topography and climate, Norway has a larger number of different habitats than almost any other European country. There are approximately 60,000 species in Norway and adjacent waters (excluding bacteria and viruses). The Norwegian Shelf large marine ecosystem is considered highly productive.[118]

Climate

Köppen climate classification types of Norway 1980–2016 with 0C as winter threshold. Note: The map is lacking some areas with Dfb climates (shown as Dfc).

Map of Norway showing the normal precipitation (annual average). Period 1961–1990.

The southern and western parts of Norway, fully exposed to Atlantic storm fronts, experience more precipitation and have milder winters than the eastern and far northern parts. Areas to the east of the coastal mountains are in a rain shadow, and have lower rain and snow totals than the west. The lowlands around Oslo have the warmest summers, but also cold weather and snow in wintertime. The sunniest weather is along the south coast, but sometimes even the coast far north can be very sunny – the sunniest month with 430 sun hours was recorded in Tromsø.[119][120]

Because of Norway’s high latitude, there are large seasonal variations in daylight. From late May to late July, the sun never completely descends beneath the horizon in areas north of the Arctic Circle (hence Norway’s description as the «Land of the Midnight sun»), and the rest of the country experiences up to 20 hours of daylight per day. Conversely, from late November to late January, the sun never rises above the horizon in the north, and daylight hours are very short in the rest of the country.

The coastal climate of Norway is exceptionally mild compared with areas on similar latitudes elsewhere in the world, with the Gulf Stream passing directly offshore the northern areas of the Atlantic coast, continuously warming the region in the winter. Temperature anomalies found in coastal locations are exceptional, with southern Lofoten and Bø having all monthly means above freezing (lacking a meteorological winter) in spite of being north of the Arctic Circle. The very northernmost coast of Norway would thus be ice-covered in winter if not for the Gulf Stream.[121] The east of the country has a more continental climate, and the mountain ranges have subarctic and tundra climates. There is also higher rainfall in areas exposed to the Atlantic, especially the western slopes of the mountain ranges and areas close, such as Bergen. The valleys east of the mountain ranges are the driest; some of the valleys are sheltered by mountains in most directions. Saltdal (81 m) in Nordland is the driest place with 211 millimetres (8.3 inches) precipitation annually (1991–2020). In southern Norway, Skjåk in Innlandet get 295 millimetres (11.6 inches) precipitation. Finnmarksvidda and some interior valleys of Troms receive around 400 millimetres (16 inches) annually, and the high Arctic Longyearbyen 217 millimetres (8.5 inches).[122]

Parts of southeastern Norway including parts of Mjøsa have a humid continental climates (Köppen Dfb), while the southern and western coasts and also the coast north to Bodø have a oceanic climate (Cfb), while the outer coast further north almost to North Cape have a subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc). Further inland in the south and at higher altitudes, and also in much of Northern Norway, the subarctic climate (Dfc) dominates. A small strip of land along the coast east of North Cape (including Vardø) earlier had tundra/alpine/polar climate (ET), but this is mostly gone with the updated 1991–2020 climate normals, making this also subarctic. Large parts of Norway are covered by mountains and high altitude plateaus, and about one third of the land is above the treeline and thus exhibit tundra/alpine/polar climate (ET).[119][123][124][120][125]

Biodiversity

The total number of species include 16,000 species of insects (probably 4,000 more species yet to be described), 20,000 species of algae, 1,800 species of lichen, 1,050 species of mosses, 2,800 species of vascular plants, up to 7,000 species of fungi, 450 species of birds (250 species nesting in Norway), 90 species of mammals, 45 fresh-water species of fish, 150 salt-water species of fish, 1,000 species of fresh-water invertebrates, and 3,500 species of salt-water invertebrates.[126] About 40,000 of these species have been described by science. The red list of 2010 encompasses 4,599 species.[127] Norway contains five terrestrial ecoregions: Sarmatic mixed forests, Scandinavian coastal conifer forests, Scandinavian and Russian taiga, Kola Peninsula tundra, and Scandinavian montane birch forest and grasslands.[128]

Seventeen species are listed mainly because they are endangered on a global scale, such as the European beaver, even if the population in Norway is not seen as endangered. The number of threatened and near-threatened species equals to 3,682; it includes 418 fungi species, many of which are closely associated with the small remaining areas of old-growth forests,[129] 36 bird species, and 16 species of mammals. In 2010, 2,398 species were listed as endangered or vulnerable; of these were 1250 listed as vulnerable (VU), 871 as endangered (EN), and 276 species as critically endangered (CR), among which were the grey wolf, the Arctic fox (healthy population on Svalbard) and the pool frog.[127]

The largest predator in Norwegian waters is the sperm whale, and the largest fish is the basking shark. The largest predator on land is the polar bear, while the brown bear is the largest predator on the Norwegian mainland. The largest land animal on the mainland is the elk (American English: moose). The elk in Norway is known for its size and strength and is often called skogens konge, «king of the forest».

Environment

Attractive and dramatic scenery and landscape are found throughout Norway.[130] The west coast of southern Norway and the coast of northern Norway present some of the most visually impressive coastal sceneries in the world. National Geographic has listed the Norwegian fjords as the world’s top tourist attraction.[131] The country is also home to the natural phenomena of the Midnight sun (during summer), as well as the Aurora borealis known also as the Northern lights.[132]

The 2016 Environmental Performance Index from Yale University, Columbia University and the World Economic Forum put Norway in seventeenth place, immediately below Croatia and Switzerland.[133] The index is based on environmental risks to human health, habitat loss, and changes in CO2 emissions. The index notes over-exploitation of fisheries, but not Norway’s whaling or oil exports.[134] Norway had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.98/10, ranking it 60th globally out of 172 countries.[135]

Politics and government

Norway is considered to be one of the most developed democracies and states of justice in the world. From 1814, c. 45% of men (25 years and older) had the right to vote, whereas the United Kingdom had c. 20% (1832), Sweden c. 5% (1866), and Belgium c. 1.15% (1840). Since 2010, Norway has been classified as the world’s most democratic country by the Democracy Index.[136][137][138]

According to the Constitution of Norway, which was adopted on 17 May 1814[139] and was inspired by the United States Declaration of Independence and French Revolution of 1776 and 1789, respectively, Norway is a unitary constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government, wherein the King of Norway is the head of state and the prime minister is the head of government. Power is separated among the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government, as defined by the Constitution, which serves as the country’s supreme legal document.

The monarch officially retains executive power. But following the introduction of a parliamentary system of government, the duties of the monarch have since become strictly representative and ceremonial,[140] such as the formal appointment and dismissal of the Prime Minister and other ministers in the executive government. Accordingly, the Monarch is commander-in-chief of the Norwegian Armed Forces, and serves as chief diplomatic official abroad and as a symbol of unity. Harald V of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg was crowned King of Norway in 1991, the first since the 14th century who has been born in the country.[141] Haakon, Crown Prince of Norway, is the legal and rightful heir to the throne and the Kingdom.

In practice, the Prime Minister exercises the executive powers. Constitutionally, legislative power is vested with both the government and the Parliament of Norway, but the latter is the supreme legislature and a unicameral body.[142] Norway is fundamentally structured as a representative democracy. The Parliament can pass a law by simple majority of the 169 representatives, who are elected on the basis of proportional representation from 19 constituencies for four-year terms.

150 are elected directly from the 19 constituencies, and an additional 19 seats («levelling seats») are allocated on a nationwide basis to make the representation in parliament correspond better with the popular vote for the political parties. A 4% election threshold is required for a party to gain levelling seats in Parliament.[143] There are a total of 169 members of parliament.

The Parliament of Norway, called the Storting (meaning Grand Assembly), ratifies national treaties developed by the executive branch. It can impeach members of the government if their acts are declared unconstitutional. If an indicted suspect is impeached, Parliament has the power to remove the person from office.

The position of prime minister, Norway’s head of government, is allocated to the member of Parliament who can obtain the confidence of a majority in Parliament, usually the current leader of the largest political party or, more effectively, through a coalition of parties. A single party generally does not have sufficient political power in terms of the number of seats to form a government on its own. Norway has often been ruled by minority governments.

The prime minister nominates the cabinet, traditionally drawn from members of the same political party or parties in the Storting, making up the government. The PM organises the executive government and exercises its power as vested by the Constitution.[144] Norway has a state church, the Lutheran Church of Norway, which has in recent years gradually been granted more internal autonomy in day-to-day affairs, but which still has a special constitutional status. Formerly, the PM had to have more than half the members of cabinet be members of the Church of Norway, meaning at least ten out of the 19 ministries. This rule was however removed in 2012. The issue of separation of church and state in Norway has been increasingly controversial, as many people believe it is time to change this, to reflect the growing diversity in the population. A part of this is the evolution of the public school subject Christianity, a required subject since 1739. Even the state’s loss in a battle at the European Court of Human Rights at Strasbourg[145] in 2007 did not settle the matter. As of 1 January 2017, the Church of Norway is a separate legal entity, and no longer a branch of the civil service.[146]

Through the Council of State, a privy council presided over by the monarch, the prime minister and the cabinet meet at the Royal Palace and formally consult the Monarch. All government bills need the formal approval by the monarch before and after introduction to Parliament. The Council reviews and approves all of the monarch’s actions as head of state. Although all government and parliamentary acts are decided beforehand, the privy council is an example of symbolic gesture the king retains.[141]

Members of the Storting are directly elected from party-lists proportional representation in nineteen plural-member constituencies in a national multi-party system.[147] Historically, both the Norwegian Labour Party and Conservative Party have played leading political roles. In the early 21st century, the Labour Party has been in power since the 2005 election, in a Red–Green Coalition with the Socialist Left Party and the Centre Party.[148]

Since 2005, both the Conservative Party and the Progress Party have won numerous seats in the Parliament, but not sufficient in the 2009 general election to overthrow the coalition. Commentators have pointed to the poor co-operation between the opposition parties, including the Liberals and the Christian Democrats. Jens Stoltenberg, the leader of the Labour Party, continued to have the necessary majority through his multi-party alliance to continue as PM until 2013.[149]

In national elections in September 2013, voters ended eight years of Labour rule. Two political parties, Høyre and Fremskrittspartiet, elected on promises of tax cuts, more spending on infrastructure and education, better services and stricter rules on immigration, formed a government. Coming at a time when Norway’s economy is in good condition with low unemployment, the rise of the right appeared to be based on other issues. Erna Solberg became prime minister, the second female prime minister after Gro Harlem Brundtland and the first conservative prime minister since Jan P. Syse. Solberg said her win was «a historic election victory for the right-wing parties».[150] Her centre-right government won re-election in the 2017 Norwegian parliamentary election.[102] Norway’s new centre-left cabinet under Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, the leader the Labour Party, took office on 14 October 2021.[151]

Administrative divisions

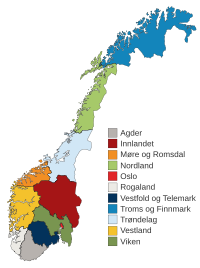

A municipal and regional reform: «On 8 June 2017, the Storting decided the following merger of counties.»

Norway, a unitary state, is divided into eleven first-level administrative counties (fylke). The counties are administered through directly elected county assemblies who elect the County Governor. Additionally, the King and government are represented in every county by a fylkesmann, who effectively acts as a Governor.[152] As such, the Government is directly represented at a local level through the County Governors’ offices. The counties are then sub-divided into 356 second-level municipalities (kommuner), which in turn are administered by directly elected municipal council, headed by a mayor and a small executive cabinet. The capital of Oslo is considered both a county and a municipality. Norway has two integral overseas territories out of mainland: Jan Mayen and Svalbard, the only developed island in the archipelago of the same name, located far to the north of the Norwegian mainland.[153]

96 settlements have city status in Norway. In most cases, the city borders are coterminous with the borders of their respective municipalities. Often, Norwegian city municipalities include large areas that are not developed; for example, Oslo municipality contains large forests, located north and southeast of the city, and over half of Bergen municipality consists of mountainous areas.

The counties of Norway are:

| Number | County (fylke) | Administrative centre | Most populous municipality | Geographical region | Total area | Population | Official language form |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 03 | City of Oslo | Oslo | Eastern Norway | 454 km2 | 673,469 | Neutral | |

| 11 | Stavanger | Stavanger | Western Norway | 9,377 km2 | 473,526 | Neutral | |

| 15 | Molde | Ålesund | Western Norway | 14,355 km2 | 266,856 | Nynorsk | |

| 18 | Bodø | Bodø | Northern Norway | 38,154 km2 | 243,335 | Neutral | |

| 30 | Oslo, Drammen, Sarpsborg and Moss | Bærum | Eastern Norway | 24,592 km2 | 1,234,374 | Neutral | |

| 34 | Hamar | Ringsaker | Eastern Norway | 52,072 km2 | 370,994 | Neutral | |

| 38 | Skien | Sandefjord | Eastern Norway | 17,465 km2 | 415,777 | Neutral | |

| 42 | Kristiansand | Kristiansand | Southern Norway | 16,434 km2 | 303,754 | Neutral | |

| 46 | Bergen | Bergen | Western Norway | 33,870 km2 | 631,594 | Nynorsk | |

| 50 | Steinkjer | Trondheim | Central Norway | 42,201 km2 | 458,744 | Neutral | |

| 54 | Tromsø | Tromsø | Northern Norway | 74,829 km2 | 243,925 | Neutral |

Dependencies of Norway

There are three Antarctic and Subantarctic dependencies: Bouvet Island, Peter I Island, and Queen Maud Land. On most maps, there had been an unclaimed area between Queen Maud Land and the South Pole until 12 June 2015 when Norway formally annexed that area.[154]

Norway and its overseas administrative divisions

Largest populated areas

Largest cities or towns in Norway According to Statistics Dec. 2018 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

Oslo  Bergen |

1 | Oslo | Oslo | 1,000,467 | 11 | Moss | Viken | 46,618 |  Stavanger/Sandnes  Trondheim |

| 2 | Bergen | Vestland | 255,464 | 12 | Haugesund | Rogaland | 44,830 | ||

| 3 | Stavanger/Sandnes | Rogaland | 222,697 | 13 | Sandefjord | Vestfold og Telemark | 43,595 | ||

| 4 | Trondheim | Trøndelag | 183,378 | 14 | Arendal | Agder | 43,084 | ||

| 5 | Drammen | Viken | 117,510 | 15 | Bodø | Nordland | 40,705 | ||

| 6 | Fredrikstad/Sarpsborg | Viken | 111,267 | 16 | Tromsø | Troms og Finnmark | 38,980 | ||

| 7 | Porsgrunn/Skien | Vestfold og Telemark | 92,753 | 17 | Hamar | Innlandet | 27,324 | ||

| 8 | Kristiansand | Agder | 61,536 | 18 | Halden | Viken | 25,300 | ||

| 9 | Ålesund | Møre og Romsdal | 52,163 | 19 | Larvik | Vestfold og Telemark | 24,208 | ||

| 10 | Tønsberg | Vestfold og Telemark | 51,571 | 20 | Askøy | Vestland | 23,194 |

Judicial system and law enforcement

Norway uses a civil law system where laws are created and amended in Parliament and the system regulated through the Courts of justice of Norway. It consists of the Supreme Court of 20 permanent judges and a Chief Justice, appellate courts, city and district courts, and conciliation councils.[155] The judiciary is independent of executive and legislative branches. While the Prime Minister nominates Supreme Court Justices for office, their nomination must be approved by Parliament and formally confirmed by the Monarch in the Council of State. Usually, judges attached to regular courts are formally appointed by the Monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister.

The Courts’ strict and formal mission is to regulate the Norwegian judicial system, interpret the Constitution, and as such implement the legislation adopted by Parliament. In its judicial reviews, it monitors the legislative and executive branches to ensure that they comply with provisions of enacted legislation.[155]

The law is enforced in Norway by the Norwegian Police Service. It is a Unified National Police Service made up of 27 Police Districts and several specialist agencies, such as Norwegian National Authority for the Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime, known as Økokrim; and the National Criminal Investigation Service, known as Kripos, each headed by a chief of police. The Police Service is headed by the National Police Directorate, which reports to the Ministry of Justice and the Police. The Police Directorate is headed by a National Police Commissioner. The only exception is the Norwegian Police Security Agency, whose head answers directly to the Ministry of Justice and the Police.

Norway abolished the death penalty for regular criminal acts in 1902. The legislature abolished the death penalty for high treason in war and war-crimes in 1979. Reporters Without Borders, in its 2007 Worldwide Press Freedom Index, ranked Norway at a shared first place (along with Iceland) out of 169 countries.[156]

In general, the legal and institutional framework in Norway is characterised by a high degree of transparency, accountability and integrity, and the perception and the occurrence of corruption are very low.[157] Norway has ratified all relevant international anti-corruption conventions, and its standards of implementation and enforcement of anti-corruption legislation are considered very high by many international anti-corruption working groups such as the OECD Anti-Bribery Working Group. However, there are some isolated cases showing that some municipalities have abused their position in public procurement processes.

Norwegian prisons are humane, rather than tough, with emphasis on rehabilitation. At 20%, Norway’s re-conviction rate is among the lowest in the world.[158]

Human rights

Norway has been considered a progressive country, which has adopted legislation and policies to support women’s rights, minority rights, and LGBT rights. As early as 1884, 171 of the leading figures, among them five Prime Ministers for the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party, co-founded the Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights.[159] They successfully campaigned for women’s right to education, women’s suffrage, the right to work, and other gender equality policies. From the 1970s, gender equality also came high on the state agenda, with the establishment of a public body to promote gender equality, which evolved into the Gender Equality and Anti-Discrimination Ombud. Civil society organisations also continue to play an important role, and the women’s rights organisations are today organised in the Norwegian Women’s Lobby umbrella organisation.

In 1990, the Norwegian constitution was amended to grant absolute primogeniture to the Norwegian throne, meaning that the eldest child, regardless of gender, takes precedence in the line of succession. As it was not retroactive, the current successor to the throne is the eldest son of the King, rather than his eldest child. The Norwegian constitution Article 6 states that «For those born before the year 1990 it shall…be the case that a male shall take precedence over a female.»[160]

The Sámi people have for centuries been the subject of discrimination and abuse by the dominant cultures in Scandinavia and Russia, those countries claiming possession of Sámi lands.[161] The Sámi people have never been a single community in a single region of Sápmi.[162] Norway has been greatly criticised by the international community for the politics of Norwegianization of and discrimination against the indigenous population of the country.[163] Nevertheless, Norway was, in 1990, the first country to recognise ILO-convention 169 on indigenous people recommended by the UN.

In regard to LGBT rights, Norway was the first country in the world to enact an anti-discrimination law protecting the rights of gays and lesbians. In 1993, Norway became the second country to legalise civil union partnerships for same-sex couples, and on 1 January 2009 Norway became the sixth country to legalise same-sex marriage. As a promoter of human rights, Norway has held the annual Oslo Freedom Forum conference, a gathering described by The Economist as «on its way to becoming a human-rights equivalent of the Davos economic forum.»[164]

Foreign relations

Norway maintains embassies in 82 countries.[165] 60 countries maintain an embassy in Norway, all of them in the capital, Oslo.

Norway is a founding member of the United Nations (UN), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Council of Europe and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Norway issued applications for accession to the European Union (EU) and its predecessors in 1962, 1967 and 1992, respectively. While Denmark, Sweden and Finland obtained membership, the Norwegian electorate rejected the treaties of accession in referendums in 1972 and 1994.

After the 1994 referendum, Norway maintained its membership in the European Economic Area (EEA), an arrangement granting the country access to the internal market of the Union, on the condition that Norway implements the Union’s pieces of legislation which are deemed relevant (of which there were approximately seven thousand by 2010)[166] Successive Norwegian governments have, since 1994, requested participation in parts of the EU’s co-operation that go beyond the provisions of the EEA agreement. Non-voting participation by Norway has been granted in, for instance, the Union’s Common Security and Defence Policy, the Schengen Agreement, and the European Defence Agency, as well as 19 separate programmes.[167]

Norway participated in the 1990s brokering of the Oslo Accords, an unsuccessful attempt to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Military

The Norwegian Armed Forces numbers about 25,000 personnel, including civilian employees. According to 2009 mobilisation plans, full mobilisation produces approximately 83,000 combatant personnel. Norway has conscription (including 6–12 months of training);[168] in 2013, the country became the first in Europe and NATO to draft women as well as men. However, due to less need for conscripts after the Cold War ended with the break-up of the Soviet Union, few people have to serve if they are not motivated.[169] The Armed Forces are subordinate to the Norwegian Ministry of Defence. The Commander-in-Chief is King Harald V. The military of Norway is divided into the following branches: the Norwegian Army, the Royal Norwegian Navy, the Royal Norwegian Air Force, the Norwegian Cyber Defence Force and the Home Guard.

In response to its being overrun by Germany in 1940, the country was one of the founding nations of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on 4 April 1949. Norway contributed in the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan.[170] Additionally, Norway has contributed in several missions in contexts of the United Nations, NATO, and the Common Security and Defence Policy of the European Union.

Economy

A proportional representation of Norway exports, 2019

Norwegians enjoy the second-highest GDP per-capita among European countries (after Luxembourg), and the sixth-highest GDP (PPP) per-capita in the world. Today, Norway ranks as the second-wealthiest country in the world in monetary value, with the largest capital reserve per capita of any nation.[171] According to the CIA World Factbook, Norway is a net external creditor of debt.[114] Norway maintained first place in the world in the UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) for six consecutive years (2001–2006), and then reclaimed this position in 2009.[28] The standard of living in Norway is among the highest in the world. Foreign Policy magazine ranks Norway last in its Failed States Index for 2009, judging Norway to be the world’s most well-functioning and stable country. The OECD ranks Norway fourth in the 2013 equalised Better Life Index and third in intergenerational earnings elasticity.[172][173]

Norway’s claimed economic zones

The Norwegian economy is an example of a mixed economy; a prosperous capitalist welfare state, it features a combination of free market activity and large state ownership in certain key sectors, influenced by both liberal governments from the late 19th century and later by social democratic governments in the postwar era. Public health care in Norway is free (after an annual charge of around 2000 kroner for those over 16), and parents have 46 weeks paid[174] parental leave. The state income derived from natural resources includes a significant contribution from petroleum production. Norway has an unemployment rate of 4.8%, with 68% of the population aged 15–74 employed.[175] People in the labour force are either employed or looking for work.[176] 9.5% of the population aged 18–66 receive a disability pension[177] and 30% of the labour force are employed by the government, the highest in the OECD.[178] The hourly productivity levels, as well as average hourly wages in Norway, are among the highest in the world.[179][180]

The egalitarian values of Norwegian society have kept the wage difference between the lowest paid worker and the CEO of most companies as much less than in comparable western economies.[181] This is also evident in Norway’s low Gini coefficient.

The state has large ownership positions in key industrial sectors, such as the strategic petroleum sector (Statoil), hydroelectric energy production (Statkraft), aluminium production (Norsk Hydro), the largest Norwegian bank (DNB), and telecommunication provider (Telenor). Through these big companies, the government controls approximately 30% of the stock values at the Oslo Stock Exchange. When non-listed companies are included, the state has even higher share in ownership (mainly from direct oil licence ownership). Norway is a major shipping nation and has the world’s sixth largest merchant fleet, with 1,412 Norwegian-owned merchant vessels.

By referendums in 1972 and 1994, Norwegians rejected proposals to join the European Union (EU). However, Norway, together with Iceland and Liechtenstein, participates in the European Union’s single market through the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement. The EEA Treaty between the European Union countries and the EFTA countries—transposed into Norwegian law via «EØS-loven»[182]—describes the procedures for implementing European Union rules in Norway and the other EFTA countries. Norway is a highly integrated member of most sectors of the EU internal market. Some sectors, such as agriculture, oil and fish, are not wholly covered by the EEA Treaty. Norway has also acceded to the Schengen Agreement and several other intergovernmental agreements among the EU member states.

The country is richly endowed with natural resources including petroleum, hydropower, fish, forests, and minerals. Large reserves of petroleum and natural gas were discovered in the 1960s, which led to a boom in the economy. Norway has obtained one of the highest standards of living in the world in part by having a large amount of natural resources compared to the size of the population. In 2011, 28% of state revenues were generated from the petroleum industry.[183]

Norway is the first country which banned cutting of trees (deforestation), in order to prevent rain forests from vanishing. The country declared its intention at the UN Climate Summit in 2014, alongside Great Britain and Germany. Crops that are typically linked to forests’ destruction are timber, soy and palm oil, while beef is also damaging. Now Norway has to find a new way to provide these essential products without exerting negative influence on its environment.[184]

Resources

Agriculture is a significant sector, in spite of the mountainous landscape (Øysand).

- Oil industry

Export revenues from oil and gas have risen to over 40% of total exports and constitute almost 20% of the GDP.[185] Norway is the fifth-largest oil exporter and third-largest gas exporter in the world, but it is not a member of OPEC. In 1995, the Norwegian government established the sovereign wealth fund («Government Pension Fund – Global»), which would be funded with oil revenues, including taxes, dividends, sales revenues and licensing fees. This was intended to reduce overheating in the economy from oil revenues, minimise uncertainty from volatility in oil price, and provide a cushion to compensate for expenses associated with the ageing of the population.