«Orthocenter» and «Orthocentre» redirect here. For the orthocentric system, see Orthocentric system.

The three altitudes of a triangle intersect at the orthocenter, which for an acute triangle is inside the triangle.

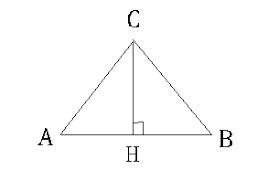

In geometry, an altitude of a triangle is a line segment through a vertex and perpendicular to (i.e., forming a right angle with) a line containing the base (the side opposite the vertex). This line containing the opposite side is called the extended base of the altitude. The intersection of the extended base and the altitude is called the foot of the altitude. The length of the altitude, often simply called «the altitude», is the distance between the extended base and the vertex. The process of drawing the altitude from the vertex to the foot is known as dropping the altitude at that vertex. It is a special case of orthogonal projection.

Altitudes can be used in the computation of the area of a triangle: one half of the product of an altitude’s length and its base’s length equals the triangle’s area. Thus, the longest altitude is perpendicular to the shortest side of the triangle. The altitudes are also related to the sides of the triangle through the trigonometric functions.

In an isosceles triangle (a triangle with two congruent sides), the altitude having the incongruent side as its base will have the midpoint of that side as its foot. Also the altitude having the incongruent side as its base will be the angle bisector of the vertex angle.

It is common to mark the altitude with the letter h (as in height), often subscripted with the name of the side the altitude is drawn to.

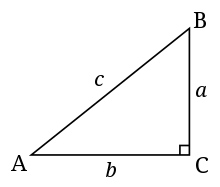

The altitude of a right triangle from its right angle to its hypotenuse is the geometric mean of the lengths of the segments the hypotenuse is split into. Using Pythagoras’ theorem on the 3 triangles of sides (p + q, r, s ), (r, p, h ) and (s, h, q ),

In a right triangle, the altitude drawn to the hypotenuse c divides the hypotenuse into two segments of lengths p and q. If we denote the length of the altitude by hc, we then have the relation

(Geometric mean theorem)

In a right triangle, the altitude from each acute angle coincides with a leg and intersects the opposite side at (has its foot at) the right-angled vertex, which is the orthocenter.

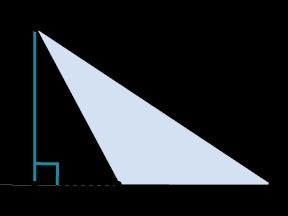

The altitudes from each of the acute angles of an obtuse triangle lie entirely outside the triangle, as does the orthocenter H.

For acute triangles the feet of the altitudes all fall on the triangle’s sides (not extended). In an obtuse triangle (one with an obtuse angle), the foot of the altitude to the obtuse-angled vertex falls in the interior of the opposite side, but the feet of the altitudes to the acute-angled vertices fall on the opposite extended side, exterior to the triangle. This is illustrated in the adjacent diagram: in this obtuse triangle, an altitude dropped perpendicularly from the top vertex, which has an acute angle, intersects the extended horizontal side outside the triangle.

Orthocenter[edit]

Three altitudes intersecting at the orthocenter

The three (possibly extended) altitudes intersect in a single point, called the orthocenter of the triangle, usually denoted by H.[1][2] The orthocenter lies inside the triangle if and only if the triangle is acute (i.e. does not have an angle greater than or equal to a right angle). If one angle is a right angle, the orthocenter coincides with the vertex at the right angle.[2]

Let A, B, C denote the vertices and also the angles of the triangle, and let

and barycentric coordinates

Since barycentric coordinates are all positive for a point in a triangle’s interior but at least one is negative for a point in the exterior, and two of the barycentric coordinates are zero for a vertex point, the barycentric coordinates given for the orthocenter show that the orthocenter is in an acute triangle’s interior, on the right-angled vertex of a right triangle, and exterior to an obtuse triangle.

In the complex plane, let the points A, B, C represent the numbers zA, zB, zC and assume that the circumcenter of triangle △ABC is located at the origin of the plane. Then, the complex number

is represented by the point H, namely the orthocenter of triangle △ABC.[4] From this, the following characterizations of the orthocenter H by means of free vectors can be established straightforwardly:

The first of the previous vector identities is also known as the problem of Sylvester, proposed by James Joseph Sylvester.[5]

Properties[edit]

Let D, E, F denote the feet of the altitudes from A, B, C respectively. Then:

- The product of the lengths of the segments that the orthocenter divides an altitude into is the same for all three altitudes:[6][7]

- The circle centered at H having radius the square root of this constant is the triangle’s polar circle.[8]

- The sum of the ratios on the three altitudes of the distance of the orthocenter from the base to the length of the altitude is 1:[9] (This property and the next one are applications of a more general property of any interior point and the three cevians through it.)

- The sum of the ratios on the three altitudes of the distance of the orthocenter from the vertex to the length of the altitude is 2:[9]

- The isogonal conjugate of the orthocenter is the circumcenter of the triangle.[10]

- The isotomic conjugate of the orthocenter is the symmedian point of the anticomplementary triangle.[11]

- Four points in the plane, such that one of them is the orthocenter of the triangle formed by the other three, is called an orthocentric system or orthocentric quadrangle.

Relation with circles and conics[edit]

Denote the circumradius of the triangle by R. Then[12][13]

In addition, denoting r as the radius of the triangle’s incircle, ra, rb, rc as the radii of its excircles, and R again as the radius of its circumcircle, the following relations hold regarding the distances of the orthocenter from the vertices:[14]

If any altitude, for example, AD, is extended to intersect the circumcircle at P, so that AD is a chord of the circumcircle, then the foot D bisects segment HP:[7]

The directrices of all parabolas that are externally tangent to one side of a triangle and tangent to the extensions of the other sides pass through the orthocenter.[15]

A circumconic passing through the orthocenter of a triangle is a rectangular hyperbola.[16]

Relation to other centers, the nine-point circle[edit]

The orthocenter H, the centroid G, the circumcenter O, and the center N of the nine-point circle all lie on a single line, known as the Euler line.[17] The center of the nine-point circle lies at the midpoint of the Euler line, between the orthocenter and the circumcenter, and the distance between the centroid and the circumcenter is half of that between the centroid and the orthocenter:[18]

The orthocenter is closer to the incenter I than it is to the centroid, and the orthocenter is farther than the incenter is from the centroid:

In terms of the sides a, b, c, inradius r and circumradius R,[19][20]: p. 449

Orthic triangle[edit]

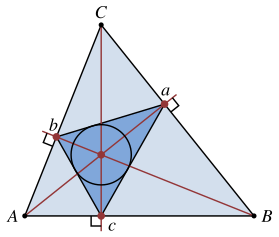

Triangle △abc (respectively, △DEF in the text) is the orthic triangle of triangle △ABC

If the triangle △ABC is oblique (does not contain a right-angle), the pedal triangle of the orthocenter of the original triangle is called the orthic triangle or altitude triangle. That is, the feet of the altitudes of an oblique triangle form the orthic triangle, △DEF. Also, the incenter (the center of the inscribed circle) of the orthic triangle △DEF is the orthocenter of the original triangle △ABC.[21]

Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the orthic triangle are given by

The extended sides of the orthic triangle meet the opposite extended sides of its reference triangle at three collinear points.[22][23][21]

In any acute triangle, the inscribed triangle with the smallest perimeter is the orthic triangle.[24] This is the solution to Fagnano’s problem, posed in 1775.[25] The sides of the orthic triangle are parallel to the tangents to the circumcircle at the original triangle’s vertices.[26]

The orthic triangle of an acute triangle gives a triangular light route.[27]

The tangent lines of the nine-point circle at the midpoints of the sides of △ABC are parallel to the sides of the orthic triangle, forming a triangle similar to the orthic triangle.[28]

The orthic triangle is closely related to the tangential triangle, constructed as follows: let LA be the line tangent to the circumcircle of triangle △ABC at vertex A, and define LB, LC analogously. Let

Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the tangential triangle are given by

The reference triangle and its orthic triangle are orthologic triangles.

For more information on the orthic triangle, see here.

Some additional altitude theorems[edit]

Altitude in terms of the sides[edit]

For any triangle with sides a, b, c and semiperimeter

This follows from combining Heron’s formula for the area of a triangle in terms of the sides with the area formula

Inradius theorems[edit]

Consider an arbitrary triangle with sides a, b, c and with corresponding

altitudes ha, hb, hc. The altitudes and the incircle radius r are related by[29]: Lemma 1

Circumradius theorem[edit]

Denoting the altitude from one side of a triangle as ha, the other two sides as b and c, and the triangle’s circumradius (radius of the triangle’s circumscribed circle) as R, the altitude is given by[30]

Interior point[edit]

If p1, p2, p3 are the perpendicular distances from any point P to the sides, and h1, h2, h3 are the altitudes to the respective sides, then[31]

Area theorem[edit]

Denoting the altitudes of any triangle from sides a, b, c respectively as ha, hb, hc, and denoting the semi-sum of the reciprocals of the altitudes as

General point on an altitude[edit]

If E is any point on an altitude AD of any triangle △ABC, then[33]: 77–78

Special cases[edit]

Equilateral triangle[edit]

For any point P within an equilateral triangle, the sum of the perpendiculars to the three sides is equal to the altitude of the triangle. This is Viviani’s theorem.

Right triangle[edit]

Comparison of the inverse Pythagorean theorem with the Pythagorean theorem

In a right triangle the three altitudes ha , hb , hc (the first two of which equal the leg lengths b and a respectively) are related according to[34][35]

This is also known as the inverse Pythagorean theorem.

History[edit]

The theorem that the three altitudes of a triangle concur (at the orthocenter) is not directly stated in surviving Greek mathematical texts, but is used in the Book of Lemmas (proposition 5), attributed to Archimedes (3rd century BC), citing the «commentary to the treatise about right-angled triangles», a work which does not survive. It was also mentioned by Pappus (Mathematical Collection, VII, 62; c. 340).[36] The theorem was stated and proved explicitly by al-Nasawi in his (11th century) commentary on the Book of Lemmas, and attributed to al-Quhi (fl. 10th century).[37]

This proof in Arabic was translated as part of the (early 17th century) Latin editions of the Book of Lemmas, but was not widely known in Europe, and the theorem was therefore proven several more times in the 17th–19th century. Samuel Marolois proved it in his Geometrie (1619), and Isaac Newton proved it in an unfinished treatise Geometry of Curved Lines (c. 1680).[36] Later William Chapple proved it in 1749.[38]

A particularly elegant proof is due to François-Joseph Servois (1804) and independently Carl Friedrich Gauss (1810): Draw a line parallel to each side of the triangle through the opposite point, and form a new triangle from the intersections of these three lines. Then the original triangle is the medial triangle of the new triangle, and the altitudes of the original triangle are the perpendicular bisectors of the new triangle, and therefore concur (at the circumcenter of the new triangle).[39]

See also[edit]

- Triangle center

- Median (geometry)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Smart 1998, p. 156

- ^ a b Berele & Goldman 2001, p. 118

- ^ Clark Kimberling’s Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers «Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers». Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ Andreescu, Titu; Andrica, Dorin, «Complex numbers from A to…Z». Birkhäuser, Boston, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8176-4326-3, page 90, Proposition 3

- ^ Dörrie, Heinrich, «100 Great Problems of Elementary Mathematics. Their History and Solution». Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1965, ISBN 0-486-61348-8, page 142

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 163, Section 255

- ^ a b ««Orthocenter of a triangle»«. Archived from the original on 2012-07-05. Retrieved 2012-05-04.

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 176, Section 278

- ^ a b Panapoi,Ronnachai, «Some properties of the orthocenter of a triangle», University of Georgia.

- ^ Smart 1998, p. 182

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Isotomic conjugate» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/IsotomicConjugate.html

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Orthocenter.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ^ Altshiller-Court 2007, p. 102

- ^ Bell, Amy, «Hansen’s right triangle theorem, its converse and a generalization», Forum Geometricorum 6, 2006, 335–342.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Kiepert Parabola.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/KiepertParabola.html

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Jerabek Hyperbola.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/JerabekHyperbola.html

- ^ Berele & Goldman 2001, p. 123

- ^ Berele & Goldman 2001, pp. 124-126

- ^ Marie-Nicole Gras, «Distances between the circumcenter of the extouch triangle and the classical centers», Forum Geometricorum 14 (2014), 51-61. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2014volume14/FG201405index.html

- ^ a b Smith, Geoff, and Leversha, Gerry, «Euler and triangle geometry», Mathematical Gazette 91, November 2007, 436–452.

- ^ a b

William H. Barker, Roger Howe (2007). «§ VI.2: The classical coincidences». Continuous symmetry: from Euclid to Klein. American Mathematical Society. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-8218-3900-3. See also: Corollary 5.5, p. 318. - ^ Johnson 2007, p. 199, Section 315

- ^ Altshiller-Court 2007, p. 165

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 168, Section 264

- ^ Berele & Goldman 2001, pp. 120-122

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 172, Section 270c

- ^ Bryant, V., and Bradley, H., «Triangular Light Routes,» Mathematical Gazette 82, July 1998, 298-299.

- ^ Kay, David C. (1993), College Geometry / A Discovery Approach, HarperCollins, p. 6, ISBN 0-06-500006-4

- ^ Dorin Andrica and Dan S ̧tefan Marinescu. «New Interpolation Inequalities to Euler’s R ≥ 2r». Forum Geometricorum, Volume 17 (2017), pp. 149–156. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2017volume17/FG201719.pdf

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 71, Section 101a

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 74, Section 103c

- ^ Mitchell, Douglas W., «A Heron-type formula for the reciprocal area of a triangle,» Mathematical Gazette 89, November 2005, 494.

- ^ Alfred S. Posamentier and Charles T. Salkind, Challenging Problems in Geometry, Dover Publishing Co., second revised edition, 1996.

- ^ Voles, Roger, «Integer solutions of

,» Mathematical Gazette 83, July 1999, 269–271.

- ^ Richinick, Jennifer, «The upside-down Pythagorean Theorem,» Mathematical Gazette 92, July 2008, 313–317.

- ^ a b

Newton, Isaac (1971). «3.1 The ‘Geometry of Curved Lines’«. In Whiteside, Derek Thomas (ed.). The Mathematical Papers of Isaac Newton. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press. pp. 454–455. Note Whiteside’s footnotes 90–92, pp. 454–456. - ^ Hajja, Mowaffaq; Martini, Horst (2013). «Concurrency of the Altitudes of a Triangle» (PDF). Mathematische Semesterberichte. 60 (2): 249–260. doi:10.1007/s00591-013-0123-z.

Hogendijk, Jan P. (2008). «Two beautiful geometrical theorems by Abū Sahl Kūhī in a 17th century Dutch translation». Tārīk͟h-e ʾElm: Iranian Journal for the History of Science. 6: 1–36. - ^ Davies, Thomas Stephens (1850). «XXIV. Geometry and geometers». Philosophical Magazine. 3. 37 (249): 198–212. doi:10.1080/14786445008646583. Footnote on pp. 207–208. Quoted by Bogomolny, Alexander (2010). «A Possibly First Proof of the Concurrence of Altitudes». Cut The Knot. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- ^

Servois, Francois-Joseph (1804). Solutions peu connues de différens problèmes de Géométrie-pratique [Little-known solutions of various Geometry practice problems] (in French). Devilly, Metz et Courcier. p. 15.

Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1810). «Zusätze». Geometrie der Stellung. By Carnot, Lazare (in German). Translated by Schumacher. republished in Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1873). «Zusätze». Werke. Vol. 4. Göttingen Academy of Sciences. p. 396.

See Mackay, John Sturgeon (1883). «The Triangle and its Six Scribed Circles §5. Orthocentre». Proceedings of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society. 1: 60–96. doi:10.1017/S0013091500036762.

References[edit]

- Altshiller-Court, Nathan (2007) [1952], College Geometry, Dover

- Berele, Allan; Goldman, Jerry (2001), Geometry: Theorems and Constructions, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-087121-4

- Bogomolny, Alexander. «Existence of the Orthocenter». Cut the Knot. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- Johnson, Roger A. (2007) [1960], Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0

- Smart, James R. (1998), Modern Geometries (5th ed.), Brooks/Cole, ISBN 0-534-35188-3

External links[edit]

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Altitude». MathWorld.

- Orthocenter of a triangle With interactive animation

- Animated demonstration of orthocenter construction Compass and straightedge.

- Fagnano’s Problem by Jay Warendorff, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

«Orthocenter» and «Orthocentre» redirect here. For the orthocentric system, see Orthocentric system.

The three altitudes of a triangle intersect at the orthocenter, which for an acute triangle is inside the triangle.

In geometry, an altitude of a triangle is a line segment through a vertex and perpendicular to (i.e., forming a right angle with) a line containing the base (the side opposite the vertex). This line containing the opposite side is called the extended base of the altitude. The intersection of the extended base and the altitude is called the foot of the altitude. The length of the altitude, often simply called «the altitude», is the distance between the extended base and the vertex. The process of drawing the altitude from the vertex to the foot is known as dropping the altitude at that vertex. It is a special case of orthogonal projection.

Altitudes can be used in the computation of the area of a triangle: one half of the product of an altitude’s length and its base’s length equals the triangle’s area. Thus, the longest altitude is perpendicular to the shortest side of the triangle. The altitudes are also related to the sides of the triangle through the trigonometric functions.

In an isosceles triangle (a triangle with two congruent sides), the altitude having the incongruent side as its base will have the midpoint of that side as its foot. Also the altitude having the incongruent side as its base will be the angle bisector of the vertex angle.

It is common to mark the altitude with the letter h (as in height), often subscripted with the name of the side the altitude is drawn to.

The altitude of a right triangle from its right angle to its hypotenuse is the geometric mean of the lengths of the segments the hypotenuse is split into. Using Pythagoras’ theorem on the 3 triangles of sides (p + q, r, s ), (r, p, h ) and (s, h, q ),

In a right triangle, the altitude drawn to the hypotenuse c divides the hypotenuse into two segments of lengths p and q. If we denote the length of the altitude by hc, we then have the relation

(Geometric mean theorem)

In a right triangle, the altitude from each acute angle coincides with a leg and intersects the opposite side at (has its foot at) the right-angled vertex, which is the orthocenter.

The altitudes from each of the acute angles of an obtuse triangle lie entirely outside the triangle, as does the orthocenter H.

For acute triangles the feet of the altitudes all fall on the triangle’s sides (not extended). In an obtuse triangle (one with an obtuse angle), the foot of the altitude to the obtuse-angled vertex falls in the interior of the opposite side, but the feet of the altitudes to the acute-angled vertices fall on the opposite extended side, exterior to the triangle. This is illustrated in the adjacent diagram: in this obtuse triangle, an altitude dropped perpendicularly from the top vertex, which has an acute angle, intersects the extended horizontal side outside the triangle.

Orthocenter[edit]

Three altitudes intersecting at the orthocenter

The three (possibly extended) altitudes intersect in a single point, called the orthocenter of the triangle, usually denoted by H.[1][2] The orthocenter lies inside the triangle if and only if the triangle is acute (i.e. does not have an angle greater than or equal to a right angle). If one angle is a right angle, the orthocenter coincides with the vertex at the right angle.[2]

Let A, B, C denote the vertices and also the angles of the triangle, and let

and barycentric coordinates

Since barycentric coordinates are all positive for a point in a triangle’s interior but at least one is negative for a point in the exterior, and two of the barycentric coordinates are zero for a vertex point, the barycentric coordinates given for the orthocenter show that the orthocenter is in an acute triangle’s interior, on the right-angled vertex of a right triangle, and exterior to an obtuse triangle.

In the complex plane, let the points A, B, C represent the numbers zA, zB, zC and assume that the circumcenter of triangle △ABC is located at the origin of the plane. Then, the complex number

is represented by the point H, namely the orthocenter of triangle △ABC.[4] From this, the following characterizations of the orthocenter H by means of free vectors can be established straightforwardly:

The first of the previous vector identities is also known as the problem of Sylvester, proposed by James Joseph Sylvester.[5]

Properties[edit]

Let D, E, F denote the feet of the altitudes from A, B, C respectively. Then:

- The product of the lengths of the segments that the orthocenter divides an altitude into is the same for all three altitudes:[6][7]

- The circle centered at H having radius the square root of this constant is the triangle’s polar circle.[8]

- The sum of the ratios on the three altitudes of the distance of the orthocenter from the base to the length of the altitude is 1:[9] (This property and the next one are applications of a more general property of any interior point and the three cevians through it.)

- The sum of the ratios on the three altitudes of the distance of the orthocenter from the vertex to the length of the altitude is 2:[9]

- The isogonal conjugate of the orthocenter is the circumcenter of the triangle.[10]

- The isotomic conjugate of the orthocenter is the symmedian point of the anticomplementary triangle.[11]

- Four points in the plane, such that one of them is the orthocenter of the triangle formed by the other three, is called an orthocentric system or orthocentric quadrangle.

Relation with circles and conics[edit]

Denote the circumradius of the triangle by R. Then[12][13]

In addition, denoting r as the radius of the triangle’s incircle, ra, rb, rc as the radii of its excircles, and R again as the radius of its circumcircle, the following relations hold regarding the distances of the orthocenter from the vertices:[14]

If any altitude, for example, AD, is extended to intersect the circumcircle at P, so that AD is a chord of the circumcircle, then the foot D bisects segment HP:[7]

The directrices of all parabolas that are externally tangent to one side of a triangle and tangent to the extensions of the other sides pass through the orthocenter.[15]

A circumconic passing through the orthocenter of a triangle is a rectangular hyperbola.[16]

Relation to other centers, the nine-point circle[edit]

The orthocenter H, the centroid G, the circumcenter O, and the center N of the nine-point circle all lie on a single line, known as the Euler line.[17] The center of the nine-point circle lies at the midpoint of the Euler line, between the orthocenter and the circumcenter, and the distance between the centroid and the circumcenter is half of that between the centroid and the orthocenter:[18]

The orthocenter is closer to the incenter I than it is to the centroid, and the orthocenter is farther than the incenter is from the centroid:

In terms of the sides a, b, c, inradius r and circumradius R,[19][20]: p. 449

Orthic triangle[edit]

Triangle △abc (respectively, △DEF in the text) is the orthic triangle of triangle △ABC

If the triangle △ABC is oblique (does not contain a right-angle), the pedal triangle of the orthocenter of the original triangle is called the orthic triangle or altitude triangle. That is, the feet of the altitudes of an oblique triangle form the orthic triangle, △DEF. Also, the incenter (the center of the inscribed circle) of the orthic triangle △DEF is the orthocenter of the original triangle △ABC.[21]

Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the orthic triangle are given by

The extended sides of the orthic triangle meet the opposite extended sides of its reference triangle at three collinear points.[22][23][21]

In any acute triangle, the inscribed triangle with the smallest perimeter is the orthic triangle.[24] This is the solution to Fagnano’s problem, posed in 1775.[25] The sides of the orthic triangle are parallel to the tangents to the circumcircle at the original triangle’s vertices.[26]

The orthic triangle of an acute triangle gives a triangular light route.[27]

The tangent lines of the nine-point circle at the midpoints of the sides of △ABC are parallel to the sides of the orthic triangle, forming a triangle similar to the orthic triangle.[28]

The orthic triangle is closely related to the tangential triangle, constructed as follows: let LA be the line tangent to the circumcircle of triangle △ABC at vertex A, and define LB, LC analogously. Let

Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the tangential triangle are given by

The reference triangle and its orthic triangle are orthologic triangles.

For more information on the orthic triangle, see here.

Some additional altitude theorems[edit]

Altitude in terms of the sides[edit]

For any triangle with sides a, b, c and semiperimeter

This follows from combining Heron’s formula for the area of a triangle in terms of the sides with the area formula

Inradius theorems[edit]

Consider an arbitrary triangle with sides a, b, c and with corresponding

altitudes ha, hb, hc. The altitudes and the incircle radius r are related by[29]: Lemma 1

Circumradius theorem[edit]

Denoting the altitude from one side of a triangle as ha, the other two sides as b and c, and the triangle’s circumradius (radius of the triangle’s circumscribed circle) as R, the altitude is given by[30]

Interior point[edit]

If p1, p2, p3 are the perpendicular distances from any point P to the sides, and h1, h2, h3 are the altitudes to the respective sides, then[31]

Area theorem[edit]

Denoting the altitudes of any triangle from sides a, b, c respectively as ha, hb, hc, and denoting the semi-sum of the reciprocals of the altitudes as

General point on an altitude[edit]

If E is any point on an altitude AD of any triangle △ABC, then[33]: 77–78

Special cases[edit]

Equilateral triangle[edit]

For any point P within an equilateral triangle, the sum of the perpendiculars to the three sides is equal to the altitude of the triangle. This is Viviani’s theorem.

Right triangle[edit]

Comparison of the inverse Pythagorean theorem with the Pythagorean theorem

In a right triangle the three altitudes ha , hb , hc (the first two of which equal the leg lengths b and a respectively) are related according to[34][35]

This is also known as the inverse Pythagorean theorem.

History[edit]

The theorem that the three altitudes of a triangle concur (at the orthocenter) is not directly stated in surviving Greek mathematical texts, but is used in the Book of Lemmas (proposition 5), attributed to Archimedes (3rd century BC), citing the «commentary to the treatise about right-angled triangles», a work which does not survive. It was also mentioned by Pappus (Mathematical Collection, VII, 62; c. 340).[36] The theorem was stated and proved explicitly by al-Nasawi in his (11th century) commentary on the Book of Lemmas, and attributed to al-Quhi (fl. 10th century).[37]

This proof in Arabic was translated as part of the (early 17th century) Latin editions of the Book of Lemmas, but was not widely known in Europe, and the theorem was therefore proven several more times in the 17th–19th century. Samuel Marolois proved it in his Geometrie (1619), and Isaac Newton proved it in an unfinished treatise Geometry of Curved Lines (c. 1680).[36] Later William Chapple proved it in 1749.[38]

A particularly elegant proof is due to François-Joseph Servois (1804) and independently Carl Friedrich Gauss (1810): Draw a line parallel to each side of the triangle through the opposite point, and form a new triangle from the intersections of these three lines. Then the original triangle is the medial triangle of the new triangle, and the altitudes of the original triangle are the perpendicular bisectors of the new triangle, and therefore concur (at the circumcenter of the new triangle).[39]

See also[edit]

- Triangle center

- Median (geometry)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Smart 1998, p. 156

- ^ a b Berele & Goldman 2001, p. 118

- ^ Clark Kimberling’s Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers «Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers». Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ Andreescu, Titu; Andrica, Dorin, «Complex numbers from A to…Z». Birkhäuser, Boston, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8176-4326-3, page 90, Proposition 3

- ^ Dörrie, Heinrich, «100 Great Problems of Elementary Mathematics. Their History and Solution». Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1965, ISBN 0-486-61348-8, page 142

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 163, Section 255

- ^ a b ««Orthocenter of a triangle»«. Archived from the original on 2012-07-05. Retrieved 2012-05-04.

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 176, Section 278

- ^ a b Panapoi,Ronnachai, «Some properties of the orthocenter of a triangle», University of Georgia.

- ^ Smart 1998, p. 182

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Isotomic conjugate» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/IsotomicConjugate.html

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Orthocenter.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ^ Altshiller-Court 2007, p. 102

- ^ Bell, Amy, «Hansen’s right triangle theorem, its converse and a generalization», Forum Geometricorum 6, 2006, 335–342.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Kiepert Parabola.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/KiepertParabola.html

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Jerabek Hyperbola.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/JerabekHyperbola.html

- ^ Berele & Goldman 2001, p. 123

- ^ Berele & Goldman 2001, pp. 124-126

- ^ Marie-Nicole Gras, «Distances between the circumcenter of the extouch triangle and the classical centers», Forum Geometricorum 14 (2014), 51-61. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2014volume14/FG201405index.html

- ^ a b Smith, Geoff, and Leversha, Gerry, «Euler and triangle geometry», Mathematical Gazette 91, November 2007, 436–452.

- ^ a b

William H. Barker, Roger Howe (2007). «§ VI.2: The classical coincidences». Continuous symmetry: from Euclid to Klein. American Mathematical Society. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-8218-3900-3. See also: Corollary 5.5, p. 318. - ^ Johnson 2007, p. 199, Section 315

- ^ Altshiller-Court 2007, p. 165

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 168, Section 264

- ^ Berele & Goldman 2001, pp. 120-122

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 172, Section 270c

- ^ Bryant, V., and Bradley, H., «Triangular Light Routes,» Mathematical Gazette 82, July 1998, 298-299.

- ^ Kay, David C. (1993), College Geometry / A Discovery Approach, HarperCollins, p. 6, ISBN 0-06-500006-4

- ^ Dorin Andrica and Dan S ̧tefan Marinescu. «New Interpolation Inequalities to Euler’s R ≥ 2r». Forum Geometricorum, Volume 17 (2017), pp. 149–156. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2017volume17/FG201719.pdf

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 71, Section 101a

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 74, Section 103c

- ^ Mitchell, Douglas W., «A Heron-type formula for the reciprocal area of a triangle,» Mathematical Gazette 89, November 2005, 494.

- ^ Alfred S. Posamentier and Charles T. Salkind, Challenging Problems in Geometry, Dover Publishing Co., second revised edition, 1996.

- ^ Voles, Roger, «Integer solutions of

,» Mathematical Gazette 83, July 1999, 269–271.

- ^ Richinick, Jennifer, «The upside-down Pythagorean Theorem,» Mathematical Gazette 92, July 2008, 313–317.

- ^ a b

Newton, Isaac (1971). «3.1 The ‘Geometry of Curved Lines’«. In Whiteside, Derek Thomas (ed.). The Mathematical Papers of Isaac Newton. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press. pp. 454–455. Note Whiteside’s footnotes 90–92, pp. 454–456. - ^ Hajja, Mowaffaq; Martini, Horst (2013). «Concurrency of the Altitudes of a Triangle» (PDF). Mathematische Semesterberichte. 60 (2): 249–260. doi:10.1007/s00591-013-0123-z.

Hogendijk, Jan P. (2008). «Two beautiful geometrical theorems by Abū Sahl Kūhī in a 17th century Dutch translation». Tārīk͟h-e ʾElm: Iranian Journal for the History of Science. 6: 1–36. - ^ Davies, Thomas Stephens (1850). «XXIV. Geometry and geometers». Philosophical Magazine. 3. 37 (249): 198–212. doi:10.1080/14786445008646583. Footnote on pp. 207–208. Quoted by Bogomolny, Alexander (2010). «A Possibly First Proof of the Concurrence of Altitudes». Cut The Knot. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- ^

Servois, Francois-Joseph (1804). Solutions peu connues de différens problèmes de Géométrie-pratique [Little-known solutions of various Geometry practice problems] (in French). Devilly, Metz et Courcier. p. 15.

Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1810). «Zusätze». Geometrie der Stellung. By Carnot, Lazare (in German). Translated by Schumacher. republished in Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1873). «Zusätze». Werke. Vol. 4. Göttingen Academy of Sciences. p. 396.

See Mackay, John Sturgeon (1883). «The Triangle and its Six Scribed Circles §5. Orthocentre». Proceedings of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society. 1: 60–96. doi:10.1017/S0013091500036762.

References[edit]

- Altshiller-Court, Nathan (2007) [1952], College Geometry, Dover

- Berele, Allan; Goldman, Jerry (2001), Geometry: Theorems and Constructions, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-087121-4

- Bogomolny, Alexander. «Existence of the Orthocenter». Cut the Knot. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- Johnson, Roger A. (2007) [1960], Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0

- Smart, James R. (1998), Modern Geometries (5th ed.), Brooks/Cole, ISBN 0-534-35188-3

External links[edit]

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Altitude». MathWorld.

- Orthocenter of a triangle With interactive animation

- Animated demonstration of orthocenter construction Compass and straightedge.

- Fagnano’s Problem by Jay Warendorff, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

Практически каждый раз при решении задач по математике, физике или другим дисциплинам приходится выбирать обозначения тех или иных величин. Среди них следует различать обозначения общепринятые (или даже устанавливаемые нормативными документами) и обозначения, выбор которых обычно выполняется самостоятельно, в зависимости от индивидуальных предпочтений. Есть также величины, обозначения которых в разных дисциплинах приняты свои. Есть обозначения международные, а есть – принятые различными в разных странах.

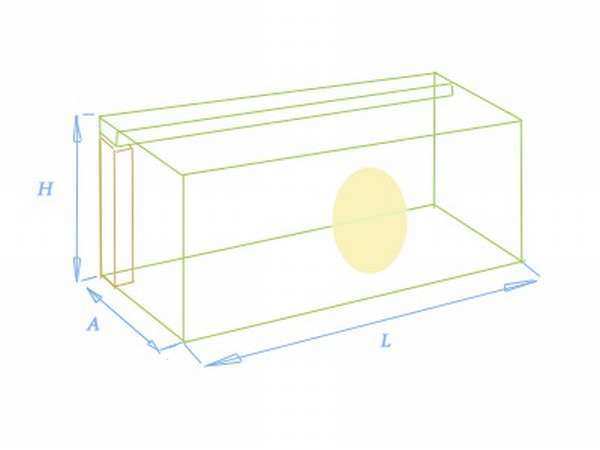

Как обозначается длина, ширина, высота, толщина, глубина

Обозначение длины в математике обычно зависит от того, какой объект в данном случае рассматривается: одномерный, двумерный или трехмерный. Если речь идёт об обозначении длины одномерного объекта (нити, проволоки и т.п.) или обозначении длины куска сортового проката (трубы, швеллера, двутавра и т.п.), то длина обычно обозначается буквой l (написанной курсивом, т.е. с наклоном, чтобы не было похоже на «единицу») или L. Если же речь идёт о двумерном объекте, в котором нужно обозначить не только длину, но и ширину, то обычно принимают одну из таких пар обозначений: a и b (а – длина, b — ширина), l и b (l – длина, b — ширина), l и h (l – длина, h — высота). Для обозначений могут быть использованы и соответствующие заглавные буквы, в литературе часто встречается сочетание L, B, H (L – длина, В – ширина, Н — высота). Эти же буквы приняты и в физике для обозначения длины, ширины, высоты объектов. Если же речь идёт о длине волны, то она обозначается строчной греческой буквой «лямбда».

Высота обозначается обычно буквой h (читается: [аш]). В технической литературе для обозначения высоты также используют букву Н (читается: [аш]). Этими же буквами (h, реже Н) обозначается глубина.

Толщина в физике обозначается либо строчной (маленькой) буквой s, либо греческой строчной буквой «дельта», с использованием (при необходимости) нижних индексов (обычно – числовых, соответствующих номеру слоя, т.е. 1, 2, 3, 4 и т.д.).

Вопросы «как в математике пишется длина», «как в математике пишется периметр», «как в математике пишется площадь» некорректны. Здесь уместно вместо слова «пишется» употребить слово «обозначается».

Как обозначается периметр

При решении задач по геометрии часто возникает необходимость обозначить периметр. Периметр в математике обозначается заглавной (т.е. большой) буквой Р (читается: [пэ]).

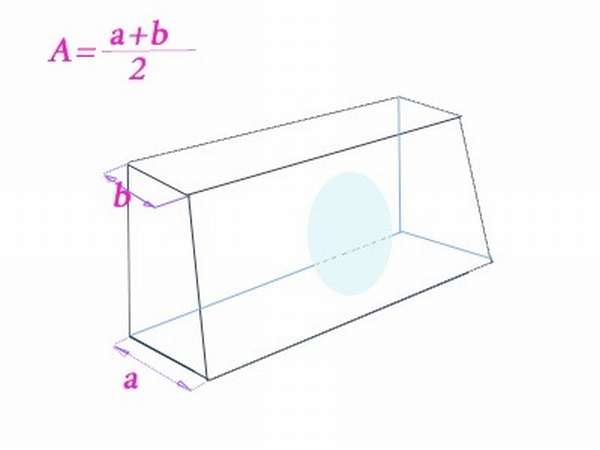

Как обозначается площадь

Обозначение площади в научно-технической литературе можно встретить различные. Поэтому и возникают вопросы «Как обозначается площадь в математике», «Как обозначается площадь в физике» и т.п. Ответ на вопрос о том, какой буквой обозначается площадь, зависит от конкретной дисциплины, о которой в данный момент идёт речь. В математике и в физике площадь обозначается буквой S заглавной (читается: [эс]). Так, в геометрии этой буквой обозначается площадь любых фигур (треугольника, прямоугольника, квадрата, ромба и т.п.). Если нужно в одной задаче обозначить площадь нескольких фигур, то используются нижние индексы. В качестве индекса могут быть использованы числа (1, 2, 3 и т.д.), т.е. площади обозначаются как S1, S2, S3 и т.д., а могут быть использованы сокращения от названия фигур (Sтр, Sпр, Sкв, Sр и т.п.). При необходимости обозначения в одной задаче площадей нескольких треугольников чаще в качестве нижнего индекса принимают обозначения этих треугольников (например, SABC, SMNP, SLPH со значком треугольника перед буквами ABC, MNP, LPH). В физике обозначается площадь поперечного сечения той же буквой S, при необходимости – с добавлением нижнего индекса (например, S1, S2, S3 и т.д.). Однако, в сопромате и в строительной механике буквой S (с добавлением индекса) обозначается не площадь, а статический момент площади относительно оси, а для обозначения площади в этих дисциплинах обычно используются буквы F (читается: [эф]) и A (читается: [а]).

Источники информации:

- Справочник по элементарной математике. Геометрия, тригонометрия, векторная алгебра/ Под ред. П.Ф. Фильчакова

- Яворский Б.М., Детлаф А.А., Лебедев А.К. Справочник по физике для инженеров и студентов вузов

- ru.wikipedia.org – список обозначений в физике

Решая геометрические задачи, ученики сталкиваются с вопросом: как правильно обозначить те или иные части чертежа? Например, высоту треугольника, ширину прямоугольника, размеры бассейна. Подобные обозначения мы найдем и в физических задачах: длина маятника, высота, с которой тело начинает падать… Поэтому следует знать некоторые правила….

Как обозначаются различные параметры

В единой системе измерения используется обозначение латинскими буквами:

- длину буквой l, если речь идет об одной прямой линии: маятнике, рычаге, отрезке, прямой. Но если речь идет о геометрической фигуре, например, прямоугольнике, то используется А,

- высоту или глубину – h,

- ширину – В.

Как обозначить глубину?

Почему же для высоты и глубины применяется одна и та же буква? Если вы построите чертеж параллелепипеда, то здесь вы отметите высоту фигуры.

А если составить чертеж прямоугольного бассейна того же размера, что и параллелепипед, то обозначается глубина. Таким образом, можно сказать, высота и глубина в этом случае будут одной величиной.

Внимание! Высота и глубина – две величины, которые обозначают один и тот же перпендикуляр, соединяющий две противоположные плоскости.

Понятие «глубина» встречается и в географии. На картах она отображается цветом. Если речь идет о водных просторах, то чем темнее синий, цвет, тем больше глубина, а если речь идет о суше, то низменности обозначаются темно-зеленым цветом.

В черчении эта величина обозначается литерой S. Она позволяет создать полное восприятие объекта иногда даже с одним видом.

Что бывает длинным

Что же такое длина и как обозначается этот показатель? Она указывает расстояние от точки до точки, то есть размер отрезка. В геометрических задачах его принято обозначать как А. В стереометрии ее могут обозначать и А, и l (например, в задачах, где встречается прямая, пересекающая плоскость).

В физике же длина маятника, плеча рычага и т.д. в «Дано» обозначается буквой l, так как речь идет об отдельной прямой.

Отличие длины от высоты

А высота – это перпендикуляр, опущенный на противолежащую плоскость.

То есть можно сделать вывод, что длина от высоты отличается тем, что является частью фигуры, совпадая с ее гранью, а высота получается в результате дополнительного построения на чертеже.

Высоту проводят для того, чтобы получить новые данные для решения задач, а также новых фигур в составе исходной.

Вот такой ширины

Ширина предмета необходима для того, чтобы понять форму как двумерного, так и трехмерного объекта. Как правило, она обозначается буквой В.

Измеряется ширина в метрах (по СИ). Но если предмет слишком мал, то для удобства используют более мелкие единицы измерения:

- дециметры,

- сантиметры,

- миллиметры,

- микрометры и т.д.

А если предмет слишком крупный, то пишутся такие приставки:

- Кило- (10³),

- Мега- (106),

- Гига- (109),

- Тера- (1012) и т.д.

Как называются стороны прямоугольника?

В отличие от квадрата, стороны прямоугольника попарно равны и параллельны.

Это значит, что стороны, образующие углы различны.

Как правило, более длинную сторону прямоугольника называют длиной, а ширина прямоугольника это его короткая сторона.

Важно! Зная такие данные, как длина и ширина прямоугольника, можно найти его периметр, площадь, длину диагоналей и угол между ними. Вокруг прямоугольника всегда можно описать окружность. Эти свойства работают и в обратном направлении.

В чем измеряются размеры длины, ширины и высоты по СИ

По единой системе измерения длина, высота и ширина измеряются в метрах. Но иногда, если это дробное или многозначное число, для удобства в вычислениях используют кратные единицы измерения.

Для того чтобы знать, как правильно переводить единицы измерения в более крупные или же наоборот мелкие, необходимо знать значения приставок.

- Дека 101,

- Гекто 102,

- Кило 103,

- Мега 106,

- Гига 109,

- Деци – 10-1,

- Санти – 10-2,

- Милли – 10-3,

- Микро 10-6,

- Нано – 10-9.

После подсчетов эти единицы должны быть переведены в метры.

Существуют также внесистемные единицы, но они встречаются очень редко:

- миля – 1,6 км,

- фут – 12 дюймов – 0,3048 м,

- ярд – 36 дюймов – 91,44 мм,

- дюйм – 25,4 мм и т.д.

При выполнении геометрических заданий единицам измерения не уделяют особого внимания, главное, чтобы они были сопоставимы

(если вы производите подсчеты в сантиметрах, значит, все величины необходимо перевести в сантиметры).

А при решении физических задач ответ должен быть дан в метрах в соответствии с единой системой измерения.

Обозначения длины, ширины, высоты в геометрии

Измеряем геометрические параметры

Вывод

Теперь вы знаете, какой буквой обозначается длина, в чем измеряется ширина прямоугольника, и сможете сами объяснить любому, как обозначаются различные параметры.

Это интересно! Легкие правила округления чисел после запятой

Высота треугольника

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 118.

Обновлено 11 Января, 2021

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 118.

Обновлено 11 Января, 2021

Почти никогда не получится определить все параметры треугольника без дополнительных построений. Эти построения являются своеобразными графическими характеристиками треугольника, которые помогают определить величину сторон и углов.

Опыт работы учителем математики — более 33 лет.

Определение

Одной из таких характеристик является высота треугольника. Высота – это перпендикуляр, проведенный из вершины треугольника к его противоположной стороне. Вершиной называют одну из трех точек, которые вместе с тремя отрезками составляют треугольник.

Определение высоты треугольника может звучать и так: высота – это перпендикуляр, проведенный из вершины треугольника к прямой, содержащей противоположную сторону.

Это определение звучит сложнее, но оно точнее отражает ситуацию. Дело в том, что в тупоугольном треугольнике не получится провести высоту внутри треугольника. Как видно на рисунке 1, высота в этом случае получается внешней. Кроме того, нестандартной ситуацией является построение высоты в прямоугольном треугольнике. В этом случае, две из трех высот треугольника будут проходить через катеты, а третья от вершины к гипотенузе.

Как правило, высоту треугольника обозначают буквой h. Также обозначается высота и в других фигурах.

Как найти высоту треугольника?

Существует три стандартных способа нахождения высоты треугольника:

Через теорему Пифагора

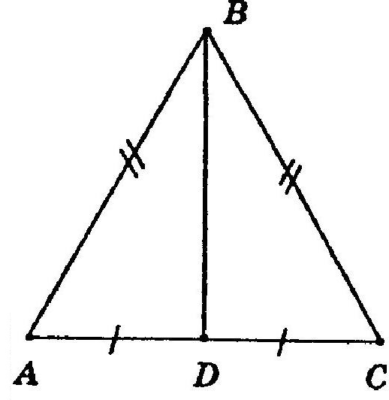

Этот способ применяется для равносторонних и равнобедренных треугольников. Разберем решение для равнобедренного треугольника, а потом скажем, почему это же решение справедливо для равностороннего.

Дано: равнобедренный треугольник АВС с основанием АС. АВ=5, АС=8. Найти высоту треугольника.

Для равнобедренного треугольника важно знать, какая именно сторона является основанием. Это определяет боковые стороны, которое должны быть равны, а так же высоту, на которую действую некоторые свойства.

Свойства высоты равнобедренного треугольника, проведенной к основанию:

- Высота совпадает с медианой и биссектрисой

- Делит основание на две равные части.

Высоту обозначим, как ВD. DС найдем как половину от основания, так как высота точкой D делит основание пополам. DС=4

Высота – это перпендикуляр, значит ВDС – прямоугольный треугольник, а высота ВD является катетом этого треугольника.

Найдем высоту по теореме Пифагора: $$BD=sqrt{BC^2-HC^2}=sqrt{25-16}=3$$

Любой равносторонний треугольник является равнобедренным, только основание у него равно боковым сторонам. То есть, можно использовать тот же порядок действий.

Через площадь треугольника

Этим способом можно пользоваться для любого треугольника. Чтобы им воспользоваться, нужно знать значение площади треугольника и стороны, к которой проведена высота.

Высоты в треугольнике не равны, поэтому для соответствующей стороны получится вычислить соответствующую высоту.

Формула площади треугольника: $$S={1over2}*bh$$, где b – это сторона треугольника ,а h – высота, проведенная к этой стороне. Выразим из формулы высоту:

$$h=2*{Sover b}$$

Если площадь равна 15, сторона 5, то высота $$h=2*{15over5}=6$$

Через тригонометрическую функцию

Третий способ подойдет, если известна сторона и угол при основании. Для этого придется воспользоваться тригонометрической функцией.

Угол ВСН=30 градусам , а сторона BC=8. У нас все тот же прямоугольный треугольник BCH. Воспользуемся определением косинуса угла прямоугольного треугольника. Косинус острого угла – это отношение прилежащего катета к гипотенузе, значит: BH/BC=cos BCH, а угол BCH равен 60 градусам, так как сумма острых углов прямоугольного треугольника равна 90 градусам.

Угол известен, как и сторона. Выразим высоту треугольника:

$$BH=BC*cos (60unicode{xb0})=8*{1over2}=4$$

Значение косинуса в общем случае берется из таблиц Брадиса, но значения тригонометрических функций для 30,45 и 60 градусов – табличные числа.

Что мы узнали?

Мы узнали, что такое высота треугольника, какие бывают высоты и как они обозначаются. Разобрались в типовых задачах и записали три формулы для высоты треугольника.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Константин Никитич

9/10

Оценка статьи

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 118.

А какая ваша оценка?

ВЫСОТА (в геометрии)

- ВЫСОТА (в геометрии)

- ВЫСОТА (в геометрии)

ВЫСОТА́, в геометрии — отрезок перпендикуляра, опущенного из вершины геометрической фигуры (напр., треугольника, пирамиды, конуса) на ее основание (или продолжение основания), а также длина этого отрезка. Высота призмы, цилиндра, шарового слоя, а также усеченных параллельно основанию пирамиды и конуса — расстояние между верхними и нижними основаниями.

Энциклопедический словарь.

2009.

Смотреть что такое «ВЫСОТА (в геометрии)» в других словарях:

-

ВЫСОТА — в геометрии отрезок перпендикуляра, опущенного из вершины геометрической фигуры (напр., треугольника, пирамиды, конуса) на ее основание (или продолжение основания), а также длина этого отрезка. Высота призмы, цилиндра, шарового слоя, а также… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Высота (геометрич.) — Высота в геометрии, отрезок перпендикуляра, опущенного из вершины геометрической фигуры (например, треугольника, пирамиды, конуса) на её основание или продолжение основания, а также длина этого отрезка. В. призмы, цилиндра, шарового слоя,… … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

Высота — I Высота небесного светила, угол между направлением на светило и плоскостью истинного горизонта; см. Небесные координаты. II Высота в геометрии, отрезок перпендикуляра, опущенного из вершины геометрической фигуры (например,… … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

ВЫСОТА — 1) ВЫСОТА в астрономии см. Небесные координаты. 2) ВЫСОТА в геометрии отрезок перпендикуляра, опущенного из вершины геом. фигуры (напр., треугольника, трапеции, пирамиды, конуса) на её основание (или продолжение основания), а также длина этого… … Большой энциклопедический политехнический словарь

-

Высота (значения) — Высота размер или расстояние в вертикальном направлении. Другие значения: В астрономии: Высота светила угол между плоскостью математического горизонта и направлением на светило. В военном деле: Высота возвышенность рельефа. В… … Википедия

-

ВЫСОТА — (1) в геометрии а) плоской фигуры наибольший из перпендикуляров, опущенных из точек контура фигуры на её основание или его продолжение; б) пространственной фигуры наибольший из перпендикуляров, опущенных из граничных точек этой фигуры на… … Большая политехническая энциклопедия

-

высота — 3.4 высота (height): Размер самой короткой кромки карты. Источник: ГОСТ Р ИСО/МЭК 15457 1 2006: Карты идентификационные. Карты тонкие гибкие. Часть 1. Физические характеристики … Словарь-справочник терминов нормативно-технической документации

-

высота здания — 3.1 высота здания : Высота здания определяется высотой расположения верхнего этажа, не считая верхнего технического этажа, а высота расположения этажа определяется разностью отметок поверхности проезда для пожарных машин и нижней границы… … Словарь-справочник терминов нормативно-технической документации

-

Высота (геометрия) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Высота (значения). Высота в элементарной геометрии отрезок перпендикуляра, опущенного из вершины геометрической фигуры (например, треугольника, пирамиды, конуса) на её основание или на… … Википедия

-

ВЫСОТА — в диофантовой геометрии некоторая численная функция на множестве решений диофантова уравнения. В простейшем случае целочисленного решения диофантова уравнения высота есть функция решения, равная В таком виде она встречается уже в методе спуска… … Математическая энциклопедия