|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copper | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | red-orange metallic luster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Cu) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copper in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 29 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1357.77 K (1084.62 °C, 1984.32 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2835 K (2562 °C, 4643 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 8.96 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 8.02 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 13.26 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 300.4 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.440 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, 0,[2] +1, +2, +3, +4 (a mildly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.90 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 128 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 132±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 140 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of copper |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | (annealed) 3810 m/s (at r.t.) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 16.5 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 401 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 16.78 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −5.46×10−6 cm3/mol[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 110–128 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 48 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 140 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.34 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 3.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 343–369 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 235–878 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-50-8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Cyprus, principal mining place in Roman era (Cyprium) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Middle East (9000 BC) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | «Cu»: from Latin cuprum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of copper

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

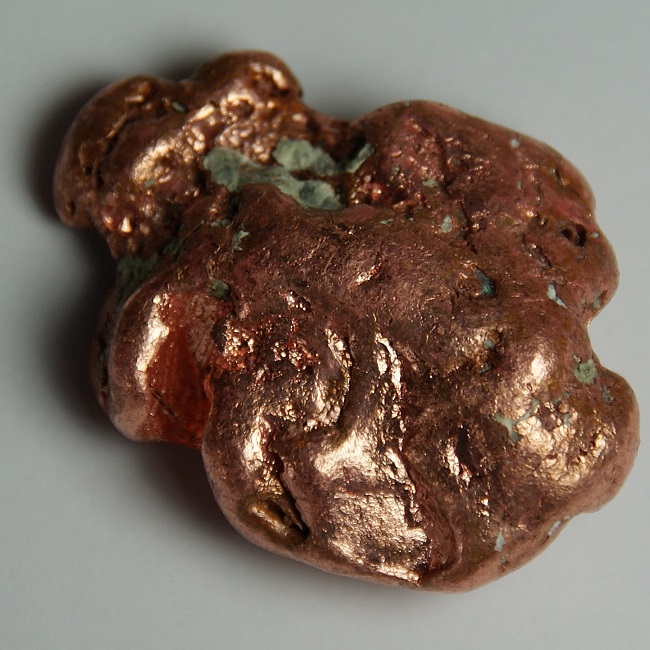

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from Latin: cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orange color. Copper is used as a conductor of heat and electricity, as a building material, and as a constituent of various metal alloys, such as sterling silver used in jewelry, cupronickel used to make marine hardware and coins, and constantan used in strain gauges and thermocouples for temperature measurement.

Copper is one of the few metals that can occur in nature in a directly usable metallic form (native metals). This led to very early human use in several regions, from circa 8000 BC. Thousands of years later, it was the first metal to be smelted from sulfide ores, circa 5000 BC; the first metal to be cast into a shape in a mold, c. 4000 BC; and the first metal to be purposely alloyed with another metal, tin, to create bronze, c. 3500 BC.[5]

In the Roman era, copper was mined principally on Cyprus, the origin of the name of the metal, from aes cyprium (metal of Cyprus), later corrupted to cuprum (Latin). Coper (Old English) and copper were derived from this, the later spelling first used around 1530.[6]

Commonly encountered compounds are copper(II) salts, which often impart blue or green colors to such minerals as azurite, malachite, and turquoise, and have been used widely and historically as pigments.

Copper used in buildings, usually for roofing, oxidizes to form a green verdigris (or patina). Copper is sometimes used in decorative art, both in its elemental metal form and in compounds as pigments. Copper compounds are used as bacteriostatic agents, fungicides, and wood preservatives.

Copper is essential to all living organisms as a trace dietary mineral because it is a key constituent of the respiratory enzyme complex cytochrome c oxidase. In molluscs and crustaceans, copper is a constituent of the blood pigment hemocyanin, replaced by the iron-complexed hemoglobin in fish and other vertebrates. In humans, copper is found mainly in the liver, muscle, and bone.[7] The adult body contains between 1.4 and 2.1 mg of copper per kilogram of body weight.[8]

Characteristics

Physical

Copper just above its melting point keeps its pink luster color when enough light outshines the orange incandescence color

Copper, silver, and gold are in group 11 of the periodic table; these three metals have one s-orbital electron on top of a filled d-electron shell and are characterized by high ductility, and electrical and thermal conductivity. The filled d-shells in these elements contribute little to interatomic interactions, which are dominated by the s-electrons through metallic bonds. Unlike metals with incomplete d-shells, metallic bonds in copper are lacking a covalent character and are relatively weak. This observation explains the low hardness and high ductility of single crystals of copper.[9] At the macroscopic scale, introduction of extended defects to the crystal lattice, such as grain boundaries, hinders flow of the material under applied stress, thereby increasing its hardness. For this reason, copper is usually supplied in a fine-grained polycrystalline form, which has greater strength than monocrystalline forms.[10]

The softness of copper partly explains its high electrical conductivity (59.6×106 S/m) and high thermal conductivity, second highest (second only to silver) among pure metals at room temperature.[11] This is because the resistivity to electron transport in metals at room temperature originates primarily from scattering of electrons on thermal vibrations of the lattice, which are relatively weak in a soft metal.[9] The maximum permissible current density of copper in open air is approximately 3.1×106 A/m2 of cross-sectional area, above which it begins to heat excessively.[12]

Copper is one of a few metallic elements with a natural color other than gray or silver.[13] Pure copper is orange-red and acquires a reddish tarnish when exposed to air. The is due to the low plasma frequency of the metal, which lies in the red part of the visible spectrum, causing it to absorb the higher-frequency green and blue colors.[14]

As with other metals, if copper is put in contact with another metal, galvanic corrosion will occur.[15]

Chemical

Unoxidized copper wire (left) and oxidized copper wire (right)

The East Tower of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, showing the contrast between the refurbished copper installed in 2010 and the green color of the original 1894 copper.

Copper does not react with water, but it does slowly react with atmospheric oxygen to form a layer of brown-black copper oxide which, unlike the rust that forms on iron in moist air, protects the underlying metal from further corrosion (passivation). A green layer of verdigris (copper carbonate) can often be seen on old copper structures, such as the roofing of many older buildings[16] and the Statue of Liberty.[17] Copper tarnishes when exposed to some sulfur compounds, with which it reacts to form various copper sulfides.[18]

Isotopes

There are 29 isotopes of copper. 63

Cu

and 65

Cu

are stable, with 63

Cu

comprising approximately 69% of naturally occurring copper; both have a spin of 3⁄2.[19] The other isotopes are radioactive, with the most stable being 67

Cu

with a half-life of 61.83 hours.[19] Seven metastable isotopes have been characterized; 68m

Cu

is the longest-lived with a half-life of 3.8 minutes. Isotopes with a mass number above 64 decay by β−, whereas those with a mass number below 64 decay by β+. 64

Cu

, which has a half-life of 12.7 hours, decays both ways.[20]

62

Cu

and 64

Cu

have significant applications. 62

Cu

is used in 62

Cu

Cu-PTSM as a radioactive tracer for positron emission tomography.[21]

Occurrence

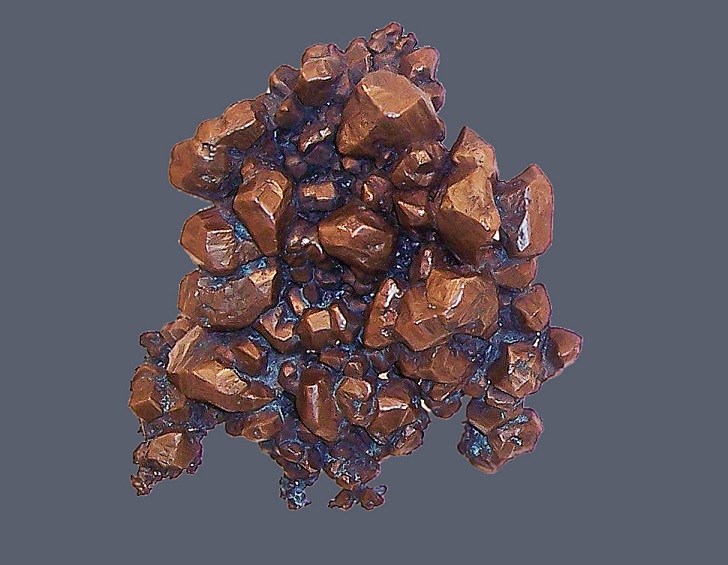

Native copper from the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, about 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) long

Copper is produced in massive stars[22] and is present in the Earth’s crust in a proportion of about 50 parts per million (ppm).[23] In nature, copper occurs in a variety of minerals, including native copper, copper sulfides such as chalcopyrite, bornite, digenite, covellite, and chalcocite, copper sulfosalts such as tetrahedite-tennantite, and enargite, copper carbonates such as azurite and malachite, and as copper(I) or copper(II) oxides such as cuprite and tenorite, respectively.[11] The largest mass of elemental copper discovered weighed 420 tonnes and was found in 1857 on the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan, US.[23] Native copper is a polycrystal, with the largest single crystal ever described measuring 4.4 × 3.2 × 3.2 cm.[24] Copper is the 25th most abundant element in Earth’s crust, representing 50 ppm compared with 75 ppm for zinc, and 14 ppm for lead.[25]

Typical background concentrations of copper do not exceed 1 ng/m3 in the atmosphere; 150 mg/kg in soil; 30 mg/kg in vegetation; 2 μg/L in freshwater and 0.5 μg/L in seawater.[26]

Production

Most copper is mined or extracted as copper sulfides from large open pit mines in porphyry copper deposits that contain 0.4 to 1.0% copper. Sites include Chuquicamata, in Chile, Bingham Canyon Mine, in Utah, United States, and El Chino Mine, in New Mexico, United States. According to the British Geological Survey, in 2005, Chile was the top producer of copper with at least one-third of the world share followed by the United States, Indonesia and Peru.[11] Copper can also be recovered through the in-situ leach process. Several sites in the state of Arizona are considered prime candidates for this method.[27] The amount of copper in use is increasing and the quantity available is barely sufficient to allow all countries to reach developed world levels of usage.[28] An alternative source of copper for collection currently being researched are polymetallic nodules, which are located at the depths of the Pacific Ocean approximately 3000–6500 meters below sea level. These nodules contain other valuable metals such as cobalt and nickel.[29]

Reserves and prices

Price of Copper 1959-2022

Copper has been in use at least 10,000 years, but more than 95% of all copper ever mined and smelted has been extracted since 1900.[30] As with many natural resources, the total amount of copper on Earth is vast, with around 1014 tons in the top kilometer of Earth’s crust, which is about 5 million years’ worth at the current rate of extraction. However, only a tiny fraction of these reserves is economically viable with present-day prices and technologies. Estimates of copper reserves available for mining vary from 25 to 60 years, depending on core assumptions such as the growth rate.[31] Recycling is a major source of copper in the modern world.[30] Because of these and other factors, the future of copper production and supply is the subject of much debate, including the concept of peak copper, analogous to peak oil.[citation needed]

The price of copper has historically been unstable,[32] and its price increased from the 60-year low of US$0.60/lb (US$1.32/kg) in June 1999 to $3.75 per pound ($8.27/kg) in May 2006. It dropped to $2.40/lb ($5.29/kg) in February 2007, then rebounded to $3.50/lb ($7.71/kg) in April 2007.[33][better source needed] In February 2009, weakening global demand and a steep fall in commodity prices since the previous year’s highs left copper prices at $1.51/lb ($3.32/kg).[34] Between September 2010 and February 2011, the price of copper rose from £5,000 a metric ton to £6,250 a metric ton.[35]

Methods

Scheme of flash smelting process

The concentration of copper in ores averages only 0.6%, and most commercial ores are sulfides, especially chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), bornite (Cu5FeS4) and, to a lesser extent, covellite (CuS) and chalcocite (Cu2S).[36] Conversely, the average concentration of copper in polymetallic nodules is estimated at 1.3%. The methods of extracting copper as well as other metals found in these nodules include sulphuric leaching, smelting and an application of the Cuprion process.[37][38] For minerals found in land ores, they are concentrated from crushed ores to the level of 10–15% copper by froth flotation or bioleaching.[39] Heating this material with silica in flash smelting removes much of the iron as slag. The process exploits the greater ease of converting iron sulfides into oxides, which in turn react with the silica to form the silicate slag that floats on top of the heated mass. The resulting copper matte, consisting of Cu2S, is roasted to convert the sulfides into oxides:[36]

- 2 Cu2S + 3 O2 → 2 Cu2O + 2 SO2

The cuprous oxide reacts with cuprous sulfide to converted to blister copper upon heating:

- 2 Cu2O + Cu2S → 6 Cu + 2 SO2

The Sudbury matte process converted only half the sulfide to oxide and then used this oxide to remove the rest of the sulfur as oxide. It was then electrolytically refined and the anode mud exploited for the platinum and gold it contained. This step exploits the relatively easy reduction of copper oxides to copper metal. Natural gas is blown across the blister to remove most of the remaining oxygen and electrorefining is performed on the resulting material to produce pure copper:[40]

- Cu2+ + 2 e− → Cu

Recycling

Like aluminium,[41] copper is recyclable without any loss of quality, both from raw state and from manufactured products.[42] In volume, copper is the third most recycled metal after iron and aluminium.[43] An estimated 80% of all copper ever mined is still in use today.[44] According to the International Resource Panel’s Metal Stocks in Society report, the global per capita stock of copper in use in society is 35–55 kg. Much of this is in more-developed countries (140–300 kg per capita) rather than less-developed countries (30–40 kg per capita).

The process of recycling copper is roughly the same as is used to extract copper but requires fewer steps. High-purity scrap copper is melted in a furnace and then reduced and cast into billets and ingots; lower-purity scrap is refined by electroplating in a bath of sulfuric acid.[45]

Alloys

Copper alloys are widely used in the production of coinage; seen here are two examples — post-1964 American dimes, which are composed of the alloy cupronickel[46] and a pre-1968 Canadian dime, which is composed of an alloy of 80 percent silver and 20 percent copper.[47]

Numerous copper alloys have been formulated, many with important uses. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. Bronze usually refers to copper-tin alloys, but can refer to any alloy of copper such as aluminium bronze. Copper is one of the most important constituents of silver and karat gold solders used in the jewelry industry, modifying the color, hardness and melting point of the resulting alloys.[48] Some lead-free solders consist of tin alloyed with a small proportion of copper and other metals.[49]

The alloy of copper and nickel, called cupronickel, is used in low-denomination coins, often for the outer cladding. The US five-cent coin (currently called a nickel) consists of 75% copper and 25% nickel in homogeneous composition. Prior to the introduction of cupronickel, which was widely adopted by countries in the latter half of the 20th century,[50] alloys of copper and silver were also used, with the United States using an alloy of 90% silver and 10% copper until 1965, when circulating silver was removed from all coins with the exception of the Half dollar — these were debased to an alloy of 40% silver and 60% copper between 1965 and 1970.[51] The alloy of 90% copper and 10% nickel, remarkable for its resistance to corrosion, is used for various objects exposed to seawater, though it is vulnerable to the sulfides sometimes found in polluted harbors and estuaries.[52] Alloys of copper with aluminium (about 7%) have a golden color and are used in decorations.[23] Shakudō is a Japanese decorative alloy of copper containing a low percentage of gold, typically 4–10%, that can be patinated to a dark blue or black color.[53]

Compounds

Copper forms a rich variety of compounds, usually with oxidation states +1 and +2, which are often called cuprous and cupric, respectively.[54] Copper compounds, whether organic complexes or organometallics, promote or catalyse numerous chemical and biological processes.[55]

Binary compounds

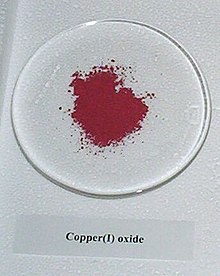

As with other elements, the simplest compounds of copper are binary compounds, i.e. those containing only two elements, the principal examples being oxides, sulfides, and halides. Both cuprous and cupric oxides are known. Among the numerous copper sulfides, important examples include copper(I) sulfide and copper(II) sulfide.[citation needed]

Cuprous halides with fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine are known, as are cupric halides with fluorine, chlorine, and bromine. Attempts to prepare copper(II) iodide yield only copper(I) iodide and iodine.[54]

- 2 Cu2+ + 4 I− → 2 CuI + I2

Coordination chemistry

Copper forms coordination complexes with ligands. In aqueous solution, copper(II) exists as [Cu(H

2O)

6]2+

. This complex exhibits the fastest water exchange rate (speed of water ligands attaching and detaching) for any transition metal aquo complex. Adding aqueous sodium hydroxide causes the precipitation of light blue solid copper(II) hydroxide. A simplified equation is:

Pourbaix diagram for copper in uncomplexed media (anions other than OH- not considered). Ion concentration 0.001 m (mol/kg water). Temperature 25 °C.

- Cu2+ + 2 OH− → Cu(OH)2

Aqueous ammonia results in the same precipitate. Upon adding excess ammonia, the precipitate dissolves, forming tetraamminecopper(II):

- Cu(H

2O)

4(OH)

2 + 4 NH3 → [Cu(H

2O)

2(NH

3)

4]2+

+ 2 H2O + 2 OH−

Many other oxyanions form complexes; these include copper(II) acetate, copper(II) nitrate, and copper(II) carbonate. Copper(II) sulfate forms a blue crystalline pentahydrate, the most familiar copper compound in the laboratory. It is used in a fungicide called the Bordeaux mixture.[56]

Polyols, compounds containing more than one alcohol functional group, generally interact with cupric salts. For example, copper salts are used to test for reducing sugars. Specifically, using Benedict’s reagent and Fehling’s solution the presence of the sugar is signaled by a color change from blue Cu(II) to reddish copper(I) oxide.[57] Schweizer’s reagent and related complexes with ethylenediamine and other amines dissolve cellulose.[58] Amino acids such as cystine form very stable chelate complexes with copper(II)[59][60][61] including in the form of metal-organic biohybrids (MOBs). Many wet-chemical tests for copper ions exist, one involving potassium ferrocyanide, which gives a brown precipitate with copper(II) salts.[citation needed]

Organocopper chemistry

Compounds that contain a carbon-copper bond are known as organocopper compounds. They are very reactive towards oxygen to form copper(I) oxide and have many uses in chemistry. They are synthesized by treating copper(I) compounds with Grignard reagents, terminal alkynes or organolithium reagents;[62] in particular, the last reaction described produces a Gilman reagent. These can undergo substitution with alkyl halides to form coupling products; as such, they are important in the field of organic synthesis. Copper(I) acetylide is highly shock-sensitive but is an intermediate in reactions such as the Cadiot-Chodkiewicz coupling[63] and the Sonogashira coupling.[64] Conjugate addition to enones[65] and carbocupration of alkynes[66] can also be achieved with organocopper compounds. Copper(I) forms a variety of weak complexes with alkenes and carbon monoxide, especially in the presence of amine ligands.[67]

Copper(III) and copper(IV)

Copper(III) is most often found in oxides. A simple example is potassium cuprate, KCuO2, a blue-black solid.[68] The most extensively studied copper(III) compounds are the cuprate superconductors. Yttrium barium copper oxide (YBa2Cu3O7) consists of both Cu(II) and Cu(III) centres. Like oxide, fluoride is a highly basic anion[69] and is known to stabilize metal ions in high oxidation states. Both copper(III) and even copper(IV) fluorides are known, K3CuF6 and Cs2CuF6, respectively.[54]

Some copper proteins form oxo complexes, which also feature copper(III).[70] With tetrapeptides, purple-colored copper(III) complexes are stabilized by the deprotonated amide ligands.[71]

Complexes of copper(III) are also found as intermediates in reactions of organocopper compounds.[72] For example, in the Kharasch–Sosnovsky reaction.[citation needed]

History

A timeline of copper illustrates how this metal has advanced human civilization for the past 11,000 years.[73]

Prehistoric

Copper Age

A corroded copper ingot from Zakros, Crete, shaped in the form of an animal skin (oxhide) typical in that era.

Many tools during the Chalcolithic Era included copper, such as the blade of this replica of Ötzi’s axe

Copper occurs naturally as native metallic copper and was known to some of the oldest civilizations on record. The history of copper use dates to 9000 BC in the Middle East;[74] a copper pendant was found in northern Iraq that dates to 8700 BC.[75] Evidence suggests that gold and meteoric iron (but not smelted iron) were the only metals used by humans before copper.[76] The history of copper metallurgy is thought to follow this sequence: First, cold working of native copper, then annealing, smelting, and, finally, lost-wax casting. In southeastern Anatolia, all four of these techniques appear more or less simultaneously at the beginning of the Neolithic c. 7500 BC.[77]

Copper smelting was independently invented in different places. It was probably discovered in China before 2800 BC, in Central America around 600 AD, and in West Africa about the 9th or 10th century AD.[78] Investment casting was invented in 4500–4000 BC in Southeast Asia[74] and carbon dating has established mining at Alderley Edge in Cheshire, UK, at 2280 to 1890 BC.[79] Ötzi the Iceman, a male dated from 3300 to 3200 BC, was found with an axe with a copper head 99.7% pure; high levels of arsenic in his hair suggest an involvement in copper smelting.[80] Experience with copper has assisted the development of other metals; in particular, copper smelting led to the discovery of iron smelting.[80] Production in the Old Copper Complex in Michigan and Wisconsin is dated between 6000 and 3000 BC.[81][82] Natural bronze, a type of copper made from ores rich in silicon, arsenic, and (rarely) tin, came into general use in the Balkans around 5500 BC.[83]

Bronze Age

Alloying copper with tin to make bronze was first practiced about 4000 years after the discovery of copper smelting, and about 2000 years after «natural bronze» had come into general use.[84] Bronze artifacts from the Vinča culture date to 4500 BC.[85] Sumerian and Egyptian artifacts of copper and bronze alloys date to 3000 BC.[86] The Bronze Age began in Southeastern Europe around 3700–3300 BC, in Northwestern Europe about 2500 BC. It ended with the beginning of the Iron Age, 2000–1000 BC in the Near East, and 600 BC in Northern Europe. The transition between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age was formerly termed the Chalcolithic period (copper-stone), when copper tools were used with stone tools. The term has gradually fallen out of favor because in some parts of the world, the Chalcolithic and Neolithic are coterminous at both ends. Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, is of much more recent origin. It was known to the Greeks, but became a significant supplement to bronze during the Roman Empire.[86]

Ancient and post-classical

In alchemy the symbol for copper was also the symbol for the goddess and planet Venus.

In Greece, copper was known by the name chalkos (χαλκός). It was an important resource for the Romans, Greeks and other ancient peoples. In Roman times, it was known as aes Cyprium, aes being the generic Latin term for copper alloys and Cyprium from Cyprus, where much copper was mined. The phrase was simplified to cuprum, hence the English copper. Aphrodite (Venus in Rome) represented copper in mythology and alchemy because of its lustrous beauty and its ancient use in producing mirrors; Cyprus, the source of copper, was sacred to the goddess. The seven heavenly bodies known to the ancients were associated with the seven metals known in antiquity, and Venus was assigned to copper, both because of the connection to the goddess and because Venus was the brightest heavenly body after the Sun and Moon and so corresponded to the most lustrous and desirable metal after gold and silver.[87]

Copper was first mined in ancient Britain as early as 2100 BC. Mining at the largest of these mines, the Great Orme, continued into the late Bronze Age. Mining seems to have been largely restricted to supergene ores, which were easier to smelt. The rich copper deposits of Cornwall seem to have been largely untouched, in spite of extensive tin mining in the region, for reasons likely social and political rather than technological.[88]

In North America, copper mining began with marginal workings by Native Americans. Native copper is known to have been extracted from sites on Isle Royale with primitive stone tools between 800 and 1600.[89] Copper metallurgy was flourishing in South America, particularly in Peru around 1000 AD. Copper burial ornamentals from the 15th century have been uncovered, but the metal’s commercial production did not start until the early 20th century.[citation needed]

The cultural role of copper has been important, particularly in currency. Romans in the 6th through 3rd centuries BC used copper lumps as money. At first, the copper itself was valued, but gradually the shape and look of the copper became more important. Julius Caesar had his own coins made from brass, while Octavianus Augustus Caesar’s coins were made from Cu-Pb-Sn alloys. With an estimated annual output of around 15,000 t, Roman copper mining and smelting activities reached a scale unsurpassed until the time of the Industrial Revolution; the provinces most intensely mined were those of Hispania, Cyprus and in Central Europe.[90][91]

The gates of the Temple of Jerusalem used Corinthian bronze treated with depletion gilding.[clarification needed][citation needed] The process was most prevalent in Alexandria, where alchemy is thought to have begun.[92] In ancient India, copper was used in the holistic medical science Ayurveda for surgical instruments and other medical equipment. Ancient Egyptians (~2400 BC) used copper for sterilizing wounds and drinking water, and later to treat headaches, burns, and itching.[citation needed]

Modern

18th-century copper kettle from Norway made from Swedish copper

The Great Copper Mountain was a mine in Falun, Sweden, that operated from the 10th century to 1992. It satisfied two-thirds of Europe’s copper consumption in the 17th century and helped fund many of Sweden’s wars during that time.[93] It was referred to as the nation’s treasury; Sweden had a copper backed currency.[94]

Chalcography of the city of Vyborg at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries. The year 1709 carved on the printing plate.

Copper is used in roofing,[16] currency, and for photographic technology known as the daguerreotype. Copper was used in Renaissance sculpture, and was used to construct the Statue of Liberty; copper continues to be used in construction of various types. Copper plating and copper sheathing were widely used to protect the under-water hulls of ships, a technique pioneered by the British Admiralty in the 18th century.[95] The Norddeutsche Affinerie in Hamburg was the first modern electroplating plant, starting its production in 1876.[96] The German scientist Gottfried Osann invented powder metallurgy in 1830 while determining the metal’s atomic mass; around then it was discovered that the amount and type of alloying element (e.g., tin) to copper would affect bell tones.[citation needed]

During the rise in demand for copper for the Age of Electricity, from the 1880s until the Great Depression of the 1930s, the United States produced one third to half the world’s newly mined copper.[97] Major districts included the Keweenaw district of northern Michigan, primarily native copper deposits, which was eclipsed by the vast sulphide deposits of Butte, Montana in the late 1880s, which itself was eclipsed by porphyry deposits of the Souhwest United States, especially at Bingham Canyon, Utah and Morenci, Arizona. Introduction of open pit steam shovel mining and innovations in smelting, refining, flotation concentration and other processing steps led to mass production. Early in the twentieth century, Arizona ranked first, followed by Montana, then Utah and Michigan.[98]

Flash smelting was developed by Outokumpu in Finland and first applied at Harjavalta in 1949; the energy-efficient process accounts for 50% of the world’s primary copper production.[99]

The Intergovernmental Council of Copper Exporting Countries, formed in 1967 by Chile, Peru, Zaire and Zambia, operated in the copper market as OPEC does in oil, though it never achieved the same influence, particularly because the second-largest producer, the United States, was never a member; it was dissolved in 1988.[100]

Applications

Copper fittings for soldered plumbing joints

The major applications of copper are electrical wire (60%), roofing and plumbing (20%), and industrial machinery (15%). Copper is used mostly as a pure metal, but when greater hardness is required, it is put into such alloys as brass and bronze (5% of total use).[23] For more than two centuries, copper paint has been used on boat hulls to control the growth of plants and shellfish.[101] A small part of the copper supply is used for nutritional supplements and fungicides in agriculture.[56][102] Machining of copper is possible, although alloys are preferred for good machinability in creating intricate parts.

Wire and cable

Despite competition from other materials, copper remains the preferred electrical conductor in nearly all categories of electrical wiring except overhead electric power transmission where aluminium is often preferred.[103][104] Copper wire is used in power generation, power transmission, power distribution, telecommunications, electronics circuitry, and countless types of electrical equipment.[105] Electrical wiring is the most important market for the copper industry.[106] This includes structural power wiring, power distribution cable, appliance wire, communications cable, automotive wire and cable, and magnet wire. Roughly half of all copper mined is used for electrical wire and cable conductors.[107] Many electrical devices rely on copper wiring because of its multitude of inherent beneficial properties, such as its high electrical conductivity, tensile strength, ductility, creep (deformation) resistance, corrosion resistance, low thermal expansion, high thermal conductivity, ease of soldering, malleability, and ease of installation.

For a short period from the late 1960s to the late 1970s, copper wiring was replaced by aluminium wiring in many housing construction projects in America. The new wiring was implicated in a number of house fires and the industry returned to copper.[108]

Electronics and related devices

Copper electrical busbars distributing power to a large building

Integrated circuits and printed circuit boards increasingly feature copper in place of aluminium because of its superior electrical conductivity; heat sinks and heat exchangers use copper because of its superior heat dissipation properties. Electromagnets, vacuum tubes, cathode ray tubes, and magnetrons in microwave ovens use copper, as do waveguides for microwave radiation.[109]

Electric motors

Copper’s superior conductivity enhances the efficiency of electrical motors.[110] This is important because motors and motor-driven systems account for 43%–46% of all global electricity consumption and 69% of all electricity used by industry.[111] Increasing the mass and cross section of copper in a coil increases the efficiency of the motor. Copper motor rotors, a new technology designed for motor applications where energy savings are prime design objectives,[112][113] are enabling general-purpose induction motors to meet and exceed National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) premium efficiency standards.[114]

Renewable energy production

Renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, tidal, hydro, biomass, and geothermal have become significant sectors of the energy market.[115][116] The rapid growth of these sources in the 21st century has been prompted by increasing costs of fossil fuels as well as their environmental impact issues that significantly lowered their use.

Copper plays an important role in these renewable energy systems.[117][118][119][120][121] Copper usage averages up to five times more in renewable energy systems than in traditional power generation, such as fossil fuel and nuclear power plants.[122] Since copper is an excellent thermal and electrical conductor among engineering metals (second only to silver),[123] electrical systems that utilize copper generate and transmit energy with high efficiency and with minimum environmental impacts.

When choosing electrical conductors, facility planners and engineers factor capital investment costs of materials against operational savings due to their electrical energy efficiencies over their useful lives, plus maintenance costs. Copper often fares well in these calculations. A factor called «copper usage intensity,” is a measure of the quantity of copper necessary to install one megawatt of new power-generating capacity.

Copper wires for recycling

When planning for a new renewable power facility, engineers and product specifiers seek to avoid supply shortages of selected materials. According to the United States Geological Survey, in-ground copper reserves have increased more than 700% since 1950, from almost 100 million tonnes to 720 million tonnes in 2017, despite the fact that world refined usage has more than tripled in the last 50 years.[124] Copper resources are estimated to exceed 5,000 million tonnes.[125][126]

Bolstering the supply from copper extraction is the fact that more than 30 percent of copper installed during the last decade came from recycled sources.[127] Its recycling rate is higher than any other metal.[128]

This article discusses the role of copper in various renewable energy generation systems.

Architecture

Old copper utensils in a Jerusalem restaurant

Copper has been used since ancient times as a durable, corrosion resistant, and weatherproof architectural material.[129][130][131][132] Roofs, flashings, rain gutters, downspouts, domes, spires, vaults, and doors have been made from copper for hundreds or thousands of years. Copper’s architectural use has been expanded in modern times to include interior and exterior wall cladding, building expansion joints, radio frequency shielding, and antimicrobial and decorative indoor products such as attractive handrails, bathroom fixtures, and counter tops. Some of copper’s other important benefits as an architectural material include low thermal movement, light weight, lightning protection, and recyclability

The metal’s distinctive natural green patina has long been coveted by architects and designers. The final patina is a particularly durable layer that is highly resistant to atmospheric corrosion, thereby protecting the underlying metal against further weathering.[133][134][135] It can be a mixture of carbonate and sulfate compounds in various amounts, depending upon environmental conditions such as sulfur-containing acid rain.[136][137][138][139] Architectural copper and its alloys can also be ‘finished’ to take on a particular look, feel, or color. Finishes include mechanical surface treatments, chemical coloring, and coatings.[140]

Copper has excellent brazing and soldering properties and can be welded; the best results are obtained with gas metal arc welding.[141]

Antibiofouling

Copper is biostatic, meaning bacteria and many other forms of life will not grow on it. For this reason it has long been used to line parts of ships to protect against barnacles and mussels. It was originally used pure, but has since been superseded by Muntz metal and copper-based paint. Similarly, as discussed in copper alloys in aquaculture, copper alloys have become important netting materials in the aquaculture industry because they are antimicrobial and prevent biofouling, even in extreme conditions[142] and have strong structural and corrosion-resistant[143] properties in marine environments.

Antimicrobial

Copper-alloy touch surfaces have natural properties that destroy a wide range of microorganisms (e.g., E. coli O157:H7, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Staphylococcus, Clostridium difficile, influenza A virus, adenovirus, SARS-Cov-2, and fungi).[144][145] Indians have been using copper vessels since ancient times for storing water, even before modern science realized its antimicrobial properties.[146] Some copper alloys were proven to kill more than 99.9% of disease-causing bacteria within just two hours when cleaned regularly.[147] The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has approved the registrations of these copper alloys as «antimicrobial materials with public health benefits»;[147] that approval allows manufacturers to make legal claims to the public health benefits of products made of registered alloys. In addition, the EPA has approved a long list of antimicrobial copper products made from these alloys, such as bedrails, handrails, over-bed tables, sinks, faucets, door knobs, toilet hardware, computer keyboards, health club equipment, and shopping cart handles (for a comprehensive list, see: Antimicrobial copper-alloy touch surfaces#Approved products). Copper doorknobs are used by hospitals to reduce the transfer of disease, and Legionnaires’ disease is suppressed by copper tubing in plumbing systems.[148] Antimicrobial copper alloy products are now being installed in healthcare facilities in the U.K., Ireland, Japan, Korea, France, Denmark, and Brazil, as well as being called for in the US,[149] and in the subway transit system in Santiago, Chile, where copper-zinc alloy handrails were installed in some 30 stations between 2011 and 2014.[150][151][152]

Textile fibers can be blended with copper to create antimicrobial protective fabrics.[153][unreliable source?]

Speculative investing

Copper may be used as a speculative investment due to the predicted increase in use from worldwide infrastructure growth, and the important role it has in producing wind turbines, solar panels, and other renewable energy sources.[154][155] Another reason predicted demand increases is the fact that electric cars contain an average of 3.6 times as much copper as conventional cars, although the effect of electric cars on copper demand is debated.[156][157] Some people invest in copper through copper mining stocks, ETFs, and futures. Others store physical copper in the form of copper bars or rounds although these tend to carry a higher premium in comparison to precious metals.[158] Those who want to avoid the premiums of copper bullion alternatively store old copper wire, copper tubing or American pennies made before 1982.[159]

Folk medicine

Copper is commonly used in jewelry, and according to some folklore, copper bracelets relieve arthritis symptoms.[160] In one trial for osteoarthritis and one trial for rheumatoid arthritis, no differences is found between copper bracelet and control (non-copper) bracelet.[161][162] No evidence shows that copper can be absorbed through the skin. If it were, it might lead to copper poisoning.[163]

Compression clothing

Recently, some compression clothing with inter-woven copper has been marketed with health claims similar to the folk medicine claims. Because compression clothing is a valid treatment for some ailments, the clothing may have that benefit, but the added copper may have no benefit beyond a placebo effect.[164]

Degradation

Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas fluorescens can both mobilize solid copper as a cyanide compound.[165] The ericoid mycorrhizal fungi associated with Calluna, Erica and Vaccinium can grow in metalliferous soils containing copper.[165] The ectomycorrhizal fungus Suillus luteus protects young pine trees from copper toxicity. A sample of the fungus Aspergillus niger was found growing from gold mining solution and was found to contain cyano complexes of such metals as gold, silver, copper, iron, and zinc. The fungus also plays a role in the solubilization of heavy metal sulfides.[166]

Biological role

Rich sources of copper include oysters, beef and lamb liver, Brazil nuts, blackstrap molasses, cocoa, and black pepper. Good sources include lobster, nuts and sunflower seeds, green olives, avocados, and wheat bran.

Biochemistry

Copper proteins have diverse roles in biological electron transport and oxygen transportation, processes that exploit the easy interconversion of Cu(I) and Cu(II).[167] Copper is essential in the aerobic respiration of all eukaryotes. In mitochondria, it is found in cytochrome c oxidase, which is the last protein in oxidative phosphorylation. Cytochrome c oxidase is the protein that binds the O2 between a copper and an iron; the protein transfers 8 electrons to the O2 molecule to reduce it to two molecules of water. Copper is also found in many superoxide dismutases, proteins that catalyze the decomposition of superoxides by converting it (by disproportionation) to oxygen and hydrogen peroxide:

- Cu2+-SOD + O2− → Cu+-SOD + O2 (reduction of copper; oxidation of superoxide)

- Cu+-SOD + O2− + 2H+ → Cu2+-SOD + H2O2 (oxidation of copper; reduction of superoxide)

The protein hemocyanin is the oxygen carrier in most mollusks and some arthropods such as the horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus).[168] Because hemocyanin is blue, these organisms have blue blood rather than the red blood of iron-based hemoglobin. Structurally related to hemocyanin are the laccases and tyrosinases. Instead of reversibly binding oxygen, these proteins hydroxylate substrates, illustrated by their role in the formation of lacquers.[169] The biological role for copper commenced with the appearance of oxygen in earth’s atmosphere.[170] Several copper proteins, such as the «blue copper proteins», do not interact directly with substrates; hence they are not enzymes. These proteins relay electrons by the process called electron transfer.[169]

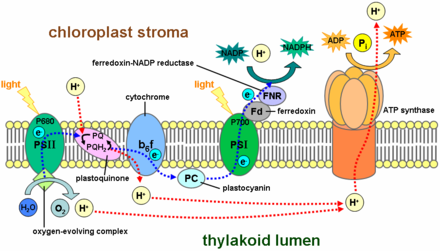

Photosynthesis functions by an elaborate electron transport chain within the thylakoid membrane. A central link in this chain is plastocyanin, a blue copper protein.

A unique tetranuclear copper center has been found in nitrous-oxide reductase.[171]

Chemical compounds which were developed for treatment of Wilson’s disease have been investigated for use in cancer therapy.[172]

Nutrition

Copper is an essential trace element in plants and animals, but not all microorganisms. The human body contains copper at a level of about 1.4 to 2.1 mg per kg of body mass.[173]

Absorption

Copper is absorbed in the gut, then transported to the liver bound to albumin.[174] After processing in the liver, copper is distributed to other tissues in a second phase, which involves the protein ceruloplasmin, carrying the majority of copper in blood. Ceruloplasmin also carries the copper that is excreted in milk, and is particularly well-absorbed as a copper source.[175] Copper in the body normally undergoes enterohepatic circulation (about 5 mg a day, vs. about 1 mg per day absorbed in the diet and excreted from the body), and the body is able to excrete some excess copper, if needed, via bile, which carries some copper out of the liver that is not then reabsorbed by the intestine.[176][177]

Dietary recommendations

The U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) updated the estimated average requirements (EARs) and recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) for copper in 2001. If there is not sufficient information to establish EARs and RDAs, an estimate designated Adequate Intake (AI) is used instead. The AIs for copper are: 200 μg of copper for 0–6-month-old males and females, and 220 μg of copper for 7–12-month-old males and females. For both sexes, the RDAs for copper are: 340 μg of copper for 1–3 years old, 440 μg of copper for 4–8 years old, 700 μg of copper for 9–13 years old, 890 μg of copper for 14–18 years old and 900 μg of copper for ages 19 years and older. For pregnancy, 1,000 μg. For lactation, 1,300 μg.[178] As for safety, the IOM also sets tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the case of copper the UL is set at 10 mg/day. Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes.[179]

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL defined the same as in United States. For women and men ages 18 and older the AIs are set at 1.3 and 1.6 mg/day, respectively. AIs for pregnancy and lactation is 1.5 mg/day. For children ages 1–17 years the AIs increase with age from 0.7 to 1.3 mg/day. These AIs are higher than the U.S. RDAs.[180] The European Food Safety Authority reviewed the same safety question and set its UL at 5 mg/day, which is half the U.S. value.[181]

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For copper labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was 2.0 mg, but as of May 27, 2016 it was revised to 0.9 mg to bring it into agreement with the RDA.[182][183] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

Deficiency

Because of its role in facilitating iron uptake, copper deficiency can produce anemia-like symptoms, neutropenia, bone abnormalities, hypopigmentation, impaired growth, increased incidence of infections, osteoporosis, hyperthyroidism, and abnormalities in glucose and cholesterol metabolism. Conversely, Wilson’s disease causes an accumulation of copper in body tissues.

Severe deficiency can be found by testing for low plasma or serum copper levels, low ceruloplasmin, and low red blood cell superoxide dismutase levels; these are not sensitive to marginal copper status. The «cytochrome c oxidase activity of leucocytes and platelets» has been stated as another factor in deficiency, but the results have not been confirmed by replication.[184]

Toxicity

Gram quantities of various copper salts have been taken in suicide attempts and produced acute copper toxicity in humans, possibly due to redox cycling and the generation of reactive oxygen species that damage DNA.[185][186] Corresponding amounts of copper salts (30 mg/kg) are toxic in animals.[187] A minimum dietary value for healthy growth in rabbits has been reported to be at least 3 ppm in the diet.[188] However, higher concentrations of copper (100 ppm, 200 ppm, or 500 ppm) in the diet of rabbits may favorably influence feed conversion efficiency, growth rates, and carcass dressing percentages.[189]

Chronic copper toxicity does not normally occur in humans because of transport systems that regulate absorption and excretion. Autosomal recessive mutations in copper transport proteins can disable these systems, leading to Wilson’s disease with copper accumulation and cirrhosis of the liver in persons who have inherited two defective genes.[173]

Elevated copper levels have also been linked to worsening symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.[190][191]

Human exposure

In the US, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has designated a permissible exposure limit (PEL) for copper dust and fumes in the workplace as a time-weighted average (TWA) of 1 mg/m3.[192] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 1 mg/m3, time-weighted average. The IDLH (immediately dangerous to life and health) value is 100 mg/m3.[193]

Copper is a constituent of tobacco smoke.[194][195] The tobacco plant readily absorbs and accumulates heavy metals, such as copper from the surrounding soil into its leaves. These are readily absorbed into the user’s body following smoke inhalation.[196] The health implications are not clear.[197]

See also

- Copper in renewable energy

- Copper nanoparticle

- Erosion corrosion of copper water tubes

- Cold water pitting of copper tube

- List of countries by copper production

- Metal theft

- Operation Tremor

- Anaconda Copper

- Antofagasta PLC

- Codelco

- El Boleo mine

- Grasberg mine

References

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Copper». CIAAW. 1969.

- ^ Moret, Marc-Etienne; Zhang, Limei; Peters, Jonas C. (2013). «A Polar Copper–Boron One-Electron σ-Bond». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (10): 3792–3795. doi:10.1021/ja4006578. PMID 23418750.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). «Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds». CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2011.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Robert McHenry, ed. (1992). «Bronze». The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (15 ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Incorporated. p. 612. ISBN 978-0-85229-553-3. OCLC 25228234.

- ^ «Copper». Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Johnson, MD PhD, Larry E., ed. (2008). «Copper». Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ «Copper in human health».

- ^ a b Trigg, George L.; Immergut, Edmund H. (1992). Encyclopedia of Applied Physics. Vol. 4: Combustion to Diamagnetism. VCH. pp. 267–272. ISBN 978-3-527-28126-8. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Smith, William F. & Hashemi, Javad (2003). Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-07-292194-6.

- ^ a b c Hammond, C. R. (2004). The Elements, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- ^ Resistance Welding Manufacturing Alliance (2003). Resistance Welding Manual (4th ed.). Resistance Welding Manufacturing Alliance. pp. 18–12. ISBN 978-0-9624382-0-2.

- ^ Chambers, William; Chambers, Robert (1884). Chambers’s Information for the People. Vol. L (5th ed.). W. & R. Chambers. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-665-46912-1.

- ^ Ramachandran, Harishankar (14 March 2007). «Why is Copper Red?» (PDF). IIT Madras. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ «Galvanic Corrosion». Corrosion Doctors. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ a b Grieken, Rene van; Janssens, Koen (2005). Cultural Heritage Conservation and Environmental Impact Assessment by Non-Destructive Testing and Micro-Analysis. CRC Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-203-97078-2.

- ^ «Copper.org: Education: Statue of Liberty: Reclothing the First Lady of Metals – Repair Concerns». Copper.org. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Rickett, B. I.; Payer, J. H. (1995). «Composition of Copper Tarnish Products Formed in Moist Air with Trace Levels of Pollutant Gas: Hydrogen Sulfide and Sulfur Dioxide/Hydrogen Sulfide». Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 142 (11): 3723–3728. Bibcode:1995JElS..142.3723R. doi:10.1149/1.2048404.

- ^ a b Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), «The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties», Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729….3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ «Interactive Chart of Nuclides». National Nuclear Data Center. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Okazawad, Hidehiko; Yonekura, Yoshiharu; Fujibayashi, Yasuhisa; Nishizawa, Sadahiko; Magata, Yasuhiro; Ishizu, Koichi; Tanaka, Fumiko; Tsuchida, Tatsuro; Tamaki, Nagara; Konishi, Junji (1994). «Clinical Application and Quantitative Evaluation of Generator-Produced Copper-62-PTSM as a Brain Perfusion Tracer for PET» (PDF). Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 35 (12): 1910–1915. PMID 7989968.

- ^ Romano, Donatella; Matteucci, Fransesca (2007). «Contrasting copper evolution in ω Centauri and the Milky Way». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 378 (1): L59–L63. arXiv:astro-ph/0703760. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.378L..59R. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2007.00320.x. S2CID 14595800.

- ^ a b c d Emsley, John (2003). Nature’s building blocks: an A–Z guide to the elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 121–125. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Rickwood, P. C. (1981). «The largest crystals» (PDF). American Mineralogist. 66: 885.

- ^ Emsley, John (2003). Nature’s building blocks: an A–Z guide to the elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 124, 231, 449, 503. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Rieuwerts, John (2015). The Elements of Environmental Pollution. London and New York: Earthscan Routledge. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-415-85919-6. OCLC 886492996.

- ^ Randazzo, Ryan (19 June 2011). «A new method to harvest copper». Azcentral.com. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ Gordon, R.B.; Bertram, M.; Graedel, T.E. (2006). «Metal stocks and sustainability». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (5): 1209–1214. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.1209G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509498103. PMC 1360560. PMID 16432205.

- ^ Beaudoin, Yannick C.; Baker, Elaine (December 2013). Deep Sea Minerals: Manganese Nodules, a physical, biological, environmental and technical review. Secretariat of the Pacific Community. pp. 7–18. ISBN 978-82-7701-119-6. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b Leonard, Andrew (3 March 2006). «Peak copper?». Salon. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Brown, Lester (2006). Plan B 2.0: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-393-32831-8.

- ^ Schmitz, Christopher (1986). «The Rise of Big Business in the World, Copper Industry 1870–1930». Economic History Review. 2. 39 (3): 392–410. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1986.tb00411.x. JSTOR 2596347.

- ^ «Copper Trends: Live Metal Spot Prices». Archived from the original on 1 May 2012.

- ^ Ackerman, R. (2 April 2009). «A Bottom in Sight For Copper». Forbes. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012.

- ^ Employment Appeal Tribunal, AEI Cables Ltd. v GMB and others, 5 April 2013, accessed 5 February 2021

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Su, Kun; Ma, Xiaodong; Parianos, John; Zhao, Baojun (2020). «Thermodynamic and Experimental Study on Efficient Extraction of Valuable Metals from Polymetallic Nodules». Minerals. 10 (4): 360. Bibcode:2020Mine…10..360S. doi:10.3390/min10040360.

- ^ International Seabed Authority. «Polymetallic Nodules» (PDF). International Seabed Authority. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Watling, H.R. (2006). «The bioleaching of sulphide minerals with emphasis on copper sulphides – A review» (PDF). Hydrometallurgy. 84 (1): 81–108. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2006.05.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2011.

- ^ Samans, Carl (1949). Engineering metals and their alloys. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 716492542.

- ^ Burton, Julie McCulloch (2015). Pen to Paper: Making Fun of Life. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4917-5394-1.

- ^ Bahadir, Ali Mufit; Duca, Gheorghe (2009). The Role of Ecological Chemistry in Pollution Research and Sustainable Development. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-2903-4.

- ^ Green, Dan (2016). The Periodic Table in Minutes. Quercus. ISBN 978-1-68144-329-4.

- ^ «International Copper Association». Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ «Overview of Recycled Copper» Copper.org. (25 August 2010). Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- ^ «Dime». US Mint. Retrieved 9 July 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Pride and skill – the 10-cent coin». Royal Canadian Mint. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ «Gold Jewellery Alloys». World Gold Council. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Balver Zinn Solder Sn97Cu3 Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF) . balverzinn.com. Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- ^ Deane, D. V. «Modern Coinage Systems» (PDF). British Numismatic Society. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ «What is 90% Silver?». American Precious Metals Exchange (APMEX). Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Corrosion Tests and Standards. ASTM International. 2005. p. 368.

- ^ Oguchi, Hachiro (1983). «Japanese Shakudō: its history, properties and production from gold-containing alloys». Gold Bulletin. 16 (4): 125–132. doi:10.1007/BF03214636.

- ^ a b c Holleman, A.F.; Wiberg, N. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ Trammell, Rachel; Rajabimoghadam, Khashayar; Garcia-Bosch, Isaac (30 January 2019). «Copper-Promoted Functionalization of Organic Molecules: from Biologically Relevant Cu/O2 Model Systems to Organometallic Transformations». Chemical Reviews. 119 (4): 2954–3031. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00368. PMC 6571019. PMID 30698952.

- ^ a b Wiley-Vch (2 April 2007). «Nonsystematic (Contact) Fungicides». Ullmann’s Agrochemicals. p. 623. ISBN 978-3-527-31604-5.

- ^ Ralph L. Shriner, Christine K.F. Hermann, Terence C. Morrill, David Y. Curtin, Reynold C. Fuson «The Systematic Identification of Organic Compounds» 8th edition, J. Wiley, Hoboken. ISBN 0-471-21503-1

- ^ Saalwächter, Kay; Burchard, Walther; Klüfers, Peter; Kettenbach, G.; Mayer, Peter; Klemm, Dieter; Dugarmaa, Saran (2000). «Cellulose Solutions in Water Containing Metal Complexes». Macromolecules. 33 (11): 4094–4107. Bibcode:2000MaMol..33.4094S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.951.5219. doi:10.1021/ma991893m.

- ^ Deodhar, S., Huckaby, J., Delahoussaye, M. and DeCoster, M.A., 2014, August. High-aspect ratio bio-metallic nanocomposites for cellular interactions. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 64, No. 1, p. 012014). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/64/1/012014/meta.

- ^ Kelly, K.C., Wasserman, J.R., Deodhar, S., Huckaby, J. and DeCoster, M.A., 2015. Generation of scalable, metallic high-aspect ratio nanocomposites in a biological liquid medium. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments), (101), p.e52901. https://www.jove.com/t/52901/generation-scalable-metallic-high-aspect-ratio-nanocomposites.

- ^ Karan, A., Darder, M., Kansakar, U., Norcross, Z. and DeCoster, M.A., 2018. Integration of a Copper-Containing Biohybrid (CuHARS) with Cellulose for Subsequent Degradation and Biomedical Control. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(5), p.844. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/5/844

- ^ «Modern Organocopper Chemistry» Norbert Krause, Ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. ISBN 978-3-527-29773-3.

- ^ Berná, José; Goldup, Stephen; Lee, Ai-Lan; Leigh, David; Symes, Mark; Teobaldi, Gilberto; Zerbetto, Fransesco (26 May 2008). «Cadiot–Chodkiewicz Active Template Synthesis of Rotaxanes and Switchable Molecular Shuttles with Weak Intercomponent Interactions». Angewandte Chemie. 120 (23): 4464–4468. Bibcode:2008AngCh.120.4464B. doi:10.1002/ange.200800891.

- ^ Rafael Chinchilla & Carmen Nájera (2007). «The Sonogashira Reaction: A Booming Methodology in Synthetic Organic Chemistry». Chemical Reviews. 107 (3): 874–922. doi:10.1021/cr050992x. PMID 17305399.

- ^ «An Addition of an Ethylcopper Complex to 1-Octyne: (E)-5-Ethyl-1,4-Undecadiene» (PDF). Organic Syntheses. 64: 1. 1986. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.064.0001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2012.

- ^ Kharasch, M.S.; Tawney, P.O. (1941). «Factors Determining the Course and Mechanisms of Grignard Reactions. II. The Effect of Metallic Compounds on the Reaction between Isophorone and Methylmagnesium Bromide». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 63 (9): 2308–2316. doi:10.1021/ja01854a005.

- ^ Imai, Sadako; Fujisawa, Kiyoshi; Kobayashi, Takako; Shirasawa, Nobuhiko; Fujii, Hiroshi; Yoshimura, Tetsuhiko; Kitajima, Nobumasa; Moro-oka, Yoshihiko (1998). «63Cu NMR Study of Copper(I) Carbonyl Complexes with Various Hydrotris(pyrazolyl)borates: Correlation between 63Cu Chemical Shifts and CO Stretching Vibrations». Inorganic Chemistry. 37 (12): 3066–3070. doi:10.1021/ic970138r.

- ^ G. Brauer, ed. (1963). «Potassium Cuprate (III)». Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). NY: Academic Press. p. 1015.

- ^ Schwesinger, Reinhard; Link, Reinhard; Wenzl, Peter; Kossek, Sebastian (2006). «Anhydrous phosphazenium fluorides as sources for extremely reactive fluoride ions in solution». Chemistry: A European Journal. 12 (2): 438–45. doi:10.1002/chem.200500838. PMID 16196062.

- ^ Lewis, E.A.; Tolman, W.B. (2004). «Reactivity of Dioxygen-Copper Systems». Chemical Reviews. 104 (2): 1047–1076. doi:10.1021/cr020633r. PMID 14871149.

- ^ McDonald, M.R.; Fredericks, F.C.; Margerum, D.W. (1997). «Characterization of Copper(III)–Tetrapeptide Complexes with Histidine as the Third Residue». Inorganic Chemistry. 36 (14): 3119–3124. doi:10.1021/ic9608713. PMID 11669966.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1187. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ A Timeline of Copper Technologies, Copper Development Association, https://www.copper.org/education/history/timeline/

- ^ a b «CSA – Discovery Guides, A Brief History of Copper». Csa.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ Rayner W. Hesse (2007). Jewelrymaking through History: an Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-313-33507-5.No primary source is given in that book.

- ^ «Copper». Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ Renfrew, Colin (1990). Before civilization: the radiocarbon revolution and prehistoric Europe. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-013642-5. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Cowen, R. «Essays on Geology, History, and People: Chapter 3: Fire and Metals». Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Timberlake, S. & Prag A.J.N.W. (2005). The Archaeology of Alderley Edge: Survey, excavation and experiment in an ancient mining landscape. Oxford: John and Erica Hedges Ltd. p. 396. doi:10.30861/9781841717159. ISBN 9781841717159.

- ^ a b «CSA – Discovery Guides, A Brief History of Copper». CSA Discovery Guides. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Pleger, Thomas C. «A Brief Introduction to the Old Copper Complex of the Western Great Lakes: 4000–1000 BC», Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Forest History Association of Wisconsin, Oconto, Wisconsin, 5 October 2002, pp. 10–18.

- ^ Emerson, Thomas E. and McElrath, Dale L. Archaic Societies: Diversity and Complexity Across the Midcontinent, SUNY Press, 2009 ISBN 1-4384-2701-8.

- ^ Dainian, Fan. Chinese Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. p. 228.

- ^ Wallach, Joel. Epigenetics: The Death of the Genetic Theory of Disease Transmission.

- ^ Radivojević, Miljana; Rehren, Thilo (December 2013). «Tainted ores and the rise of tin bronzes in Eurasia, c. 6500 years ago». Antiquity Publications Ltd.

- ^ a b McNeil, Ian (2002). Encyclopaedia of the History of Technology. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 13, 48–66. ISBN 978-0-203-19211-5.

- ^ Rickard, T.A. (1932). «The Nomenclature of Copper and its Alloys». Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 62: 281–290. doi:10.2307/2843960. JSTOR 2843960.

- ^ Timberlake, Simon (11 June 2017). «New ideas on the exploitation of copper, tin, gold, and lead ores in Bronze Age Britain: The mining, smelting, and movement of metal». Materials and Manufacturing Processes. 32 (7–8): 709–727. doi:10.1080/10426914.2016.1221113. S2CID 138178474.

- ^ Martin, Susan R. (1995). «The State of Our Knowledge About Ancient Copper Mining in Michigan». The Michigan Archaeologist. 41 (2–3): 119. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016.

- ^ Hong, S.; Candelone, J.-P.; Patterson, C.C.; Boutron, C.F. (1996). «History of Ancient Copper Smelting Pollution During Roman and Medieval Times Recorded in Greenland Ice». Science. 272 (5259): 246–249 (247f.). Bibcode:1996Sci…272..246H. doi:10.1126/science.272.5259.246. S2CID 176767223.

- ^ de Callataÿ, François (2005). «The Graeco-Roman Economy in the Super Long-Run: Lead, Copper, and Shipwrecks». Journal of Roman Archaeology. 18: 361–372 (366–369). doi:10.1017/S104775940000742X. S2CID 232346123.

- ^ Savenije, Tom J.; Warman, John M.; Barentsen, Helma M.; van Dijk, Marinus; Zuilhof, Han; Sudhölter, Ernst J.R. (2000). «Corinthian Bronze and the Gold of the Alchemists» (PDF). Macromolecules. 33 (2): 60–66. Bibcode:2000MaMol..33…60S. doi:10.1021/ma9904870. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2007.

- ^ Lynch, Martin (2004). Mining in World History. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-86189-173-0.

- ^ «Gold: prices, facts, figures and research: A brief history of money». Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ «Copper and Brass in Ships». Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Stelter, M.; Bombach, H. (2004). «Process Optimization in Copper Electrorefining». Advanced Engineering Materials. 6 (7): 558–562. doi:10.1002/adem.200400403. S2CID 138550311.

- ^ Gardner, E. D.; et al. (1938). Copper Mining in North America. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Bureau of Mines. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Hyde, Charles (1998). Copper for America, the United States Copper Industry from Colonial Times to the 1990s. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. p. passim. ISBN 0-8165-1817-3.

- ^ «Outokumpu Flash Smelting» (PDF). Outokumpu. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011.

- ^ Karen A. Mingst (1976). «Cooperation or illusion: an examination of the intergovernmental council of copper exporting countries». International Organization. 30 (2): 263–287. doi:10.1017/S0020818300018270. S2CID 154183817.

- ^ Ryck Lydecker. «Is Copper Bottom Paint Sinking?». BoatUS Magazine. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ «Copper». American Elements. 2008. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ^ Pops, Horace, 2008, «Processing of wire from antiquity to the future», Wire Journal International, June, pp. 58–66

- ^ The Metallurgy of Copper Wire, http://www.litz-wire.com/pdf%20files/Metallurgy_Copper_Wire.pdf Archived 1 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Joseph, Günter, 1999, Copper: Its Trade, Manufacture, Use, and Environmental Status, edited by Kundig, Konrad J.A., ASM International, pp. 141–192 and pp. 331–375.

- ^ «Copper, Chemical Element – Overview, Discovery and naming, Physical properties, Chemical properties, Occurrence in nature, Isotopes». Chemistryexplained.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Joseph, Günter, 1999, Copper: Its Trade, Manufacture, Use, and Environmental Status, edited by Kundig, Konrad J.A., ASM International, p.348

- ^ «Aluminum Wiring Hazards and Pre-Purchase Inspections». www.heimer.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ «Accelerator: Waveguides (SLAC VVC)». SLAC Virtual Visitor Center. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ IE3 energy-saving motors, Engineer Live, http://www.engineerlive.com/Design-Engineer/Motors_and_Drives/IE3_energy-saving_motors/22687/

- ^ Energy‐efficiency policy opportunities for electric motor‐driven systems, International Energy Agency, 2011 Working Paper in the Energy Efficiency Series, by Paul Waide and Conrad U. Brunner, OECD/IEA 2011

- ^ Fuchsloch, J. and E.F. Brush, (2007), «Systematic Design Approach for a New Series of Ultra‐NEMA Premium Copper Rotor Motors», in EEMODS 2007 Conference Proceedings, 10–15 June, Beijing.

- ^ Copper motor rotor project; Copper Development Association; «Copper.org: Copper Motor Rotor Project». Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ NEMA Premium Motors, The Association of Electrical Equipment and Medical Imaging Manufacturers; «NEMA — NEMA Premium Motors». Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ^ International Energy Agency, IEA sees renewable energy growth accelerating over next 5 years, http://www.iea.org/newsroomandevents/pressreleases/2012/july/name,28200,en.html

- ^ Global trends in renewable energy investment 2012, by REN21 (Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century); http://www.ren21.net/gsr

- ^ Will the Transition to Renewable Energy Be Paved in Copper?, Renewable Energy World; Jan 15, 2016; https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/articles/2016/01/will-the-transition-to-renewable-energy-be-paved-in-copper.html Archived 2018-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ García-Olivares, Antonio, Joaquim Ballabrera-Poy, Emili García-Ladona, and Antonio Turiel. A global renewable mix with proven technologies and common materials, Energy Policy, 41 (2012): 561-57, http://imedea.uib-csic.es/master/cambioglobal/Modulo_I_cod101601/Ballabrera_Diciembre_2011/Articulos/Garcia-Olivares.2011.pdf

- ^ A kilo more of copper increases environmental performance by 100 to 1,000 times; Renewable Energy Magazine; April 14, 2011; http://www.renewableenergymagazine.com/article/a-kilo-more-of-copper-increases-environmental

- ^ Copper at the core of renewable energies; European Copper Institute; European Copper Institute; 18 pages; http://www.eurocopper.org/files/presskit/press_kit_copper_in_renewables_final_29_10_2008.pdf Archived 2012-05-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Copper in energy systems; Copper Development Association Inc.; http://www.copper.org/environment/green/energy.html

- ^ The Rise Of Solar: A Unique Opportunity For Copper; Solar Industry Magazine; April 2017; Zolaika Strong; https://issues.solarindustrymag.com/article/rise-solar-unique-opportunity-copper

- ^ Pops, Horace, 1995. Physical Metallurgy of Electrical Conductors, in Nonferrous Wire Handbook, Volume 3: Principles and Practice, The Wire Association International

- ^ The World Copper Factbook, 2017; http://www.icsg.org/index.php/component/jdownloads/finish/170/2462

- ^ Copper Mineral Commodity Summary (USGS, 2017) https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/ mcs-2017-coppe.pdf

- ^ Global Mineral Resource Assessment (USGS, 2014) http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2014/3004/pdf/fs2014-3004.pdf

- ^ Long-Term Availability of Copper; International Copper Association; http://copperalliance.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ICA-long-term-availability-201802-A4-HR.pdf Archived 2018-06-29 at the Wayback Machine