На чтение 7 мин Просмотров 2.9к.

Содержание

- Биография Дмитрия Менделеева на английском языке

- Dmitry Mendeleyev / Дмитрий Менделеев (текст на английском с переводом)

- Интересные факты из жизни Менделеева

Дмитрий Менделеев по праву считается одним из величайших учёных не только России, но и всего мира, да и вообще всех времён и народов. Хотя большинству он людей благодаря изобретённой им таблице химических элементов, он преуспел в самых разных областях науки, и человечество обязано ему очень, очень многим. Применял он свои знания и на практике, представив обществу немало полезных приборов.

Биография Дмитрия Менделеева на английском языке

Здесь вы можете прочитать биографию Дмитрия Менделеева на английском языке.

Dmitri Mendeleev (08.02. [O.S. 27.01.] 1834 — 02.02. [O.S. 20.01.] 1907) — Russian chemist and inventor.

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev was born on 8 February 1834 near Tobolsk. He was a Russian inventor and chemist. The most famous invention of Mendeleev is periodic table of elements.

Mendeleev’s parents were Maria Mendeleeva (nee Kornilieva) and Ivan Mendeleev. According to the different sources there were approximately seventeen children in their family. Mendeleev was the youngest child. His father worked as a teacher but he became blind and stopped working. As a result Maria Mendeleeva began to work and re-established the glass factory which belonged to her family. It is also known that Mendeleev’s grandfather was a priest of the Russian Orthodox Church. When Mendeleev was 13 he entered the Gymnasium in Tobolsk.

In 1849 his family moved to Saint Petersburg. In 1850 Mendeleev joined The Main Pedagogical Institute. Following the graduation he developed tuberculosis and was forced to relocate to the Crimean Peninsula. Living there, Mendeleev became a science master of the Simferopol gymnasium #1. In 1857 after recovery he arrived in Saint Petersburg.

From 1859 to 1861 Mendeleev worked in Heidelberg and researched the capillarity of liquids. In April 1862 he married Feozva Nikitichna Leshcheva. Two years later Mendeleev became a professor at the Saint Petersburg Technological Institute. In 1865 he became a professor at Saint Petersburg State University. The same year Mendeleev completed his dissertation «On the Combinations of Water with Alcohol». By 1871 Saint Petersburg was known as a center for chemistry research. In 1876 Mendeleev fell in love with Anna Ivanova Popova. In 1881 he made a proposal of marriage to her. The following year Mendeleev married her. The same year he divorced his first wife. Mendeleev had two children from his first marriage: Olga and Vladimir. His other children from the second marriage were Lyubov, a pair of twins and son Ivan. It should be noted that Lyubov was the wife of Russian poet Alexander Blok.

Mendeleev obtained a lot of awards from different scientific organizations but he resigned from Saint Petersburg University in 1890. Three years later Mendeleev was appointed Director of the Bureau of Weights and Measures. His task was to formulate new standards of vodka. According to the new standards created by Mendeleev all vodka had to be made at forty percent alcohol by volume. He also researched the composition of petroleum and made a contribution to the foundation of the first Russian oil refinery.

In 1906 the Nobel Committee for Chemistry suggested to the Swedish Academy to award the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1906 to Mendeleev for his discovery of the periodic system. This proposal was approved. But at the full meeting of the Academy one of the members recommended the candidacy of Henri Moissan. Moreover Svante Arrhenius who had influence on the Academy also advised to reject the candidacy of Mendeleev. The contemporaries state that Arrhenius was against Mendeleev because of his critique of Arrhenius’s dissociation theory. As a result the candidacy of Mendeleev was rejected.

Dmitri Mendeleev died of influenza in Saint Petersburg in 1907.

Dmitry Mendeleyev / Дмитрий Менделеев (текст на английском с переводом)

The Russian chemist Dmitry Mendeleyev is regarded as the father of the periodic table of chemical elements.

Русский химик, Дмитрий Менделеев, считается отцом периодической таблицы химических элементов.

He studied all the elements known at the time

Он изучил все известные в то время элементы

and discovered that they showed a regular repetition of properties when arranged in a certain order.

и обнаружил, что они проявляют регулярные повторения свойств, когда расположены в определенном порядке.

He also predicted the discovery and properties of new elements.

Он также предсказал открытие и свойства новых элементов.

All of these have now been isolated and named;

Все они в настоящее время выделены и названы;

one, mendelevium, is named for Mendeleyev.

один из них, менделевиум, назван по имени Менделеева.

Mendeleyev also experimented with agricultural production based on scientific principles,

Менделеев также проводил эксперименты в сельскохозяйственном производстве, основанном на научных принципах,

increasing its efficiency to such an extent

поднимающих его производительность до таких размеров,

that his methods came to be applied in many Russian industries.

что эти методы стали применять во многих отраслях российской промышленности.

Интересные факты из жизни Менделеева

- У великого учёного было шестнадцать братьев и сестёр. В семье он был самым младшим.

- Во время обучения в педагогическом институте из-за посредственной успеваемости Дмитрий Менделеев был оставлен на второй год.

- Вопреки распространённому мифу, он не изобретал водку. Миф возник из-за публикации им научного труда о соединении воды и спирта, которая к водке как таковой никакого отношения не имела. Водку на момент публикации производили уже давным-давно.

- Около 30 лет своей жизни Менделеев посвятил работе в Санкт-Петербургском университете. Он покинул его стены в знак протеста, когда министр народного просвещения отказался принять студенческую петицию, в которой они требовали свободы слова.

- В юности он однажды встречался с Гоголем.

- Менделеев был женат дважды, у него было шестеро детей.

- Ещё один миф о Менделееве — что свою знаменитую периодическую таблицу элементов он увидел во сне. Миф этот зародился при его жизни, и, когда ему его озвучили, он обиделся, заявив, что он, может быть, лет двадцать думал над этим открытием, а ему говорят, что всё было так просто — увидел во сне, и готово.

- Великий учёный был неравнодушен к классической музыке. Своим любимым композитором он считал Бетховена.

- Племянник Менделеева был его полным тёзкой по ФИО. Из-за этого их нередко путали.

- Составляя периодическую таблицу, учёный предугадал характеристики ещё не открытых на тот момент элементов и оставил в своей таблице для них свободные места.

- Менделеев любил работать руками. Особенно хорошо ему удавалось изготовление чемоданов. Даже когда он совсем ослеп в старости, он продолжал работать на ощупь.

- Он неоднократно номинировался на Нобелевскую премию, но так её и не получил, вероятнее всего, из-за конфликта с братьями Нобелями, связанного с добываемой в Баку нефтью.

- В 1887 году Менделеев в одиночку поднялся на воздушном шаре на высоту более трёх километров, чтобы провести ряд измерений. Полёт продлился около трёх часов.

- Лишь около 10% всех работ Менделеева посвящены химии.

- Учёный написал более сорока научных трудов об арктическом мореплавании и принял активное участие в постройке «Ермака», первого в мире арктического ледокола.

Источники:

https://www.homeenglish.ru/ArticlesMendeleev.htm

http://englishon-line.ru/chtenie-nauchnii-tekst44.html

http://стофактов.рф/25-интересных-фактов-о-менделееве/

|

Dmitri Mendeleev |

|

|---|---|

Mendeleev in 1897 |

|

| Born |

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev 8 February 1834 Verkhnie Aremzyani, Tobolsk Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 2 February 1907 (aged 72)

Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg University |

| Known for | Formulating the periodic table of chemical elements |

| Spouses |

Feozva Nikitichna Leshcheva (m. 1862; div. 1882) Anna Ivanovna Popova (m. 1882) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Academic advisors | Gustav Kirchhoff |

| Signature | |

|

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (sometimes transliterated as Mendeleyev, Mendeleiev, or Mendeleef) ( MEN-dəl-AY-əf;[2] Russian: Дмитрий Иванович Менделеев,[a] tr. Dmitriy Ivanovich Mendeleyev, IPA: [ˈdmʲitrʲɪj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ mʲɪnʲdʲɪˈlʲejɪf] (listen); 8 February [O.S. 27 January] 1834 – 2 February [O.S. 20 January] 1907) was a Russian chemist and inventor. He is best known for formulating the Periodic Law and creating a version of the periodic table of elements. He used the Periodic Law not only to correct the then-accepted properties of some known elements, such as the valence and atomic weight of uranium, but also to predict the properties of three elements that were yet to be discovered.

Early life

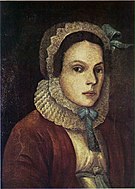

Portraits of Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleeva and Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleev (c. early 19th century)

Mendeleev was born in the village of Verkhnie Aremzyani, near Tobolsk in Siberia, to Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleev [ru] (1783–1847) and Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleeva (née Kornilieva) (1793–1850).[3][4] Ivan worked as a school principal and a teacher of fine arts, politics and philosophy at the Tambov and Saratov gymnasiums.[5] Ivan’s father, Pavel Maximovich Sokolov, was a Russian Orthodox priest from the Tver region.[6] As per the tradition of priests of that time, Pavel’s children were given new family names while attending the theological seminary,[7] with Ivan getting the family name Mendeleev after the name of a local landlord.[8]

Maria Kornilieva came from a well-known family of Tobolsk merchants, founders of the first Siberian printing house who traced their ancestry to Yakov Korniliev, a 17th-century posad man turned a wealthy merchant.[9][10] In 1889, a local librarian published an article in the Tobolsk newspaper where he claimed that Yakov was a baptized Teleut, an ethnic minority known as «white Kalmyks» at the time.[11] Since no sources were provided and no documented facts of Yakov’s life were ever revealed, biographers generally dismiss it as a myth.[12][13] In 1908, shortly after Mendeleev’s death, one of his nieces published Family Chronicles. Memories about D. I. Mendeleev where she voiced «a family legend» about Maria’s grandfather who married «a Kyrgyz or Tatar beauty whom he loved so much that when she died, he also died from grief».[14] This, however, contradicts the documented family chronicles, and neither of those legends is supported by Mendeleev’s autobiography, his daughter’s or his wife’s memoirs.[4][15][16] Yet some Western scholars still refer to Mendeleev’s supposed «Mongol», «Tatar», «Tartarian» or simply «Asian» ancestry as a fact.[17][18][19][20]

Mendeleev was raised as an Orthodox Christian, his mother encouraging him to «patiently search divine and scientific truth».[21] His son would later inform her that he departed from the Church and embraced a form of «romanticized deism».[22]

Mendeleev was the youngest of 17 siblings, of whom «only 14 stayed alive to be baptized» according to Mendeleev’s brother Pavel, meaning the others died soon after their birth.[5] The exact number of Mendeleev’s siblings differs among sources and is still a matter of some historical dispute.[23][b] Unfortunately for the family’s financial well-being, his father became blind and lost his teaching position. His mother was forced to work and she restarted her family’s abandoned glass factory. At the age of 13, after the passing of his father and the destruction of his mother’s factory by fire, Mendeleev attended the Gymnasium in Tobolsk.

In 1849, his mother took Mendeleev across Russia from Siberia to Moscow with the aim of getting Mendeleev enrolled at the Moscow University.[8] The university in Moscow did not accept him. The mother and son continued to Saint Petersburg to the father’s alma mater. The now poor Mendeleev family relocated to Saint Petersburg, where he entered the Main Pedagogical Institute in 1850. After graduation, he contracted tuberculosis, causing him to move to the Crimean Peninsula on the northern coast of the Black Sea in 1855. While there, he became a science master of the 1st Simferopol Gymnasium. In 1857, he returned to Saint Petersburg with fully restored health.

Between 1859 and 1861, he worked on the capillarity of liquids and the workings of the spectroscope in Heidelberg. Later in 1861, he published a textbook named Organic Chemistry.[26] This won him the Demidov Prize of the Petersburg Academy of Sciences.[26]

On 4 April 1862, he became engaged to Feozva Nikitichna Leshcheva, and they married on 27 April 1862 at Nikolaev Engineering Institute’s church in Saint Petersburg (where he taught).[27]

Mendeleev became a professor at the Saint Petersburg Technological Institute and Saint Petersburg State University in 1864,[26] and 1865, respectively. In 1865, he became a Doctor of Science for his dissertation «On the Combinations of Water with Alcohol». He achieved tenure in 1867 at St. Petersburg University and started to teach inorganic chemistry while succeeding Voskresenskii to this post;[26] by 1871, he had transformed Saint Petersburg into an internationally recognized center for chemistry research.

Periodic table

Mendeleev’s 1871 periodic table

Sculpture in honor of Mendeleev and the periodic table, located in Bratislava, Slovakia

In 1863, there were 56 known elements with a new element being discovered at a rate of approximately one per year. Other scientists had previously identified periodicity of elements. John Newlands described a Law of Octaves, noting their periodicity according to relative atomic weight in 1864, publishing it in 1865. His proposal identified the potential for new elements such as germanium. The concept was criticized, and his innovation was not recognized by the Society of Chemists until 1887. Another person to propose a periodic table was Lothar Meyer, who published a paper in 1864 describing 28 elements classified by their valence, but with no predictions of new elements.

After becoming a teacher in 1867, Mendeleev wrote Principles of Chemistry (Russian: Основы химии, romanized: Osnovy himii), which became the definitive textbook of its time. It was published in two volumes between 1868 and 1870, and Mendeleev wrote it as he was preparing a textbook for his course.[26] This is when he made his most important discovery.[26] As he attempted to classify the elements according to their chemical properties, he noticed patterns that led him to postulate his periodic table; he claimed to have envisioned the complete arrangement of the elements in a dream:[28][29][30][31][32]

I saw in a dream a table where all elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper, only in one place did a correction later seem necessary.

— Mendeleev, as quoted by Inostrantzev[33][34]

Unaware of the earlier work on periodic tables going on in the 1860s, he made the following table:

| Cl 35.5 | K 39 | Ca 40 |

| Br 80 | Rb 85 | Sr 88 |

| I 127 | Cs 133 | Ba 137 |

By adding additional elements following this pattern, Mendeleev developed his extended version of the periodic table.[35][36] On 6 March 1869, he made a formal presentation to the Russian Chemical Society, titled The Dependence between the Properties of the Atomic Weights of the Elements, which described elements according to both atomic weight (now called relative atomic mass) and valence.[37][38] This presentation stated that

- The elements, if arranged according to their atomic weight, exhibit an apparent periodicity of properties.

- Elements which are similar regarding their chemical properties either have similar atomic weights (e.g., Pt, Ir, Os) or have their atomic weights increasing regularly (e.g., K, Rb, Cs).

- The arrangement of the elements in groups of elements in the order of their atomic weights corresponds to their so-called valencies, as well as, to some extent, to their distinctive chemical properties; as is apparent among other series in that of Li, Be, B, C, N, O, and F.

- The elements which are the most widely diffused have small atomic weights.

- The magnitude of the atomic weight determines the character of the element, just as the magnitude of the molecule determines the character of a compound body.

- We must expect the discovery of many yet unknown elements – for example, two elements, analogous to aluminium and silicon, whose atomic weights would be between 65 and 75.

- The atomic weight of an element may sometimes be amended by a knowledge of those of its contiguous elements. Thus the atomic weight of tellurium must lie between 123 and 126, and cannot be 128. (Tellurium’s atomic weight is 127.6, and Mendeleev was incorrect in his assumption that atomic weight must increase with position within a period.)

- Certain characteristic properties of elements can be foretold from their atomic weights.

Mendeleev published his periodic table of all known elements and predicted several new elements to complete the table in a Russian-language journal. Only a few months after, Meyer published a virtually identical table in a German-language journal.[39][40] Mendeleev has the distinction of accurately predicting the properties of what he called ekasilicon, ekaaluminium and ekaboron (germanium, gallium and scandium, respectively).[41][42]

Mendeleev also proposed changes in the properties of some known elements. Prior to his work, uranium was supposed to have valence 3 and atomic weight about 120. Mendeleev realized that these values did not fit in his periodic table, and doubled both to valence 6 and atomic weight 240 (close to the modern value of 238).[43]

For his predicted three elements, he used the prefixes of eka, dvi, and tri (Sanskrit one, two, three) in their naming. Mendeleev questioned some of the currently accepted atomic weights (they could be measured only with a relatively low accuracy at that time), pointing out that they did not correspond to those suggested by his Periodic Law. He noted that tellurium has a higher atomic weight than iodine, but he placed them in the right order, incorrectly predicting that the accepted atomic weights at the time were at fault. He was puzzled about where to put the known lanthanides, and predicted the existence of another row to the table which were the actinides which were some of the heaviest in atomic weight. Some people dismissed Mendeleev for predicting that there would be more elements, but he was proven to be correct when Ga (gallium) and Ge (germanium) were found in 1875 and 1886 respectively, fitting perfectly into the two missing spaces.[44]

By using Sanskrit prefixes to name «missing» elements, Mendeleev may have recorded his debt to the Sanskrit grammarians of ancient India, who had created theories of language based on their discovery of the two-dimensional patterns of speech sounds (exemplified by the Śivasūtras in Pāṇini’s Sanskrit grammar). Mendeleev was a friend and colleague of the Sanskritist Otto von Böhtlingk, who was preparing the second edition of his book on Pāṇini[45] at about this time, and Mendeleev wished to honor Pāṇini with his nomenclature.[46][47][48]

The original draft made by Mendeleev would be found years later and published under the name Tentative System of Elements.[49]

Dmitri Mendeleev is often referred to as the Father of the Periodic Table. He called his table or matrix, «the Periodic System».[50]

Later life

Dmitri Mendeleev second wife, Anna.

In 1876, he became obsessed[citation needed] with Anna Ivanova Popova and began courting her; in 1881 he proposed to her and threatened suicide if she refused. His divorce from Leshcheva was finalized one month after he had married Popova (on 2 April)[51] in early 1882. Even after the divorce, Mendeleev was technically a bigamist; the Russian Orthodox Church required at least seven years before lawful remarriage. His divorce and the surrounding controversy contributed to his failure to be admitted to the Russian Academy of Sciences (despite his international fame by that time). His daughter from his second marriage, Lyubov, became the wife of the famous Russian poet Alexander Blok. His other children were son Vladimir (a sailor, he took part in the notable Eastern journey of Nicholas II) and daughter Olga, from his first marriage to Feozva, and son Ivan and twins from Anna.

Though Mendeleev was widely honored by scientific organizations all over Europe, including (in 1882) the Davy Medal from the Royal Society of London (which later also awarded him the Copley Medal in 1905),[52] he resigned from Saint Petersburg University on 17 August 1890. He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1892,[1] and in 1893 he was appointed director of the Bureau of Weights and Measures, a post which he occupied until his death.[52]

Mendeleev also investigated the composition of petroleum, and helped to found the first oil refinery in Russia. He recognized the importance of petroleum as a feedstock for petrochemicals. He is credited with a remark that burning petroleum as a fuel «would be akin to firing up a kitchen stove with bank notes».[53]

In 1905, Mendeleev was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The following year the Nobel Committee for Chemistry recommended to the Swedish Academy to award the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1906 to Mendeleev for his discovery of the periodic system. The Chemistry Section of the Swedish Academy supported this recommendation. The Academy was then supposed to approve the Committee’s choice, as it has done in almost every case. Unexpectedly, at the full meeting of the Academy, a dissenting member of the Nobel Committee, Peter Klason, proposed the candidacy of Henri Moissan whom he favored. Svante Arrhenius, although not a member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, had a great deal of influence in the Academy and also pressed for the rejection of Mendeleev, arguing that the periodic system was too old to acknowledge its discovery in 1906. According to the contemporaries, Arrhenius was motivated by the grudge he held against Mendeleev for his critique of Arrhenius’s dissociation theory. After heated arguments, the majority of the Academy chose Moissan by a margin of one vote.[54] The attempts to nominate Mendeleev in 1907 were again frustrated by the absolute opposition of Arrhenius.[55]

In 1907, Mendeleev died at the age of 72 in Saint Petersburg from influenza. His last words were to his physician: «Doctor, you have science, I have faith,» which is possibly a Jules Verne quote.[56]

Other achievements

Mendeleev made other important contributions to chemistry. The Russian chemist and science historian Lev Chugaev characterized him as «a chemist of genius, first-class physicist, a fruitful researcher in the fields of hydrodynamics, meteorology, geology, certain branches of chemical technology (explosives, petroleum, and fuels, for example) and other disciplines adjacent to chemistry and physics, a thorough expert of chemical industry and industry in general, and an original thinker in the field of economy.» Mendeleev was one of the founders, in 1869, of the Russian Chemical Society. He worked on the theory and practice of protectionist trade and on agriculture.

In an attempt at a chemical conception of the aether, he put forward a hypothesis that there existed two inert chemical elements of lesser atomic weight than hydrogen.[52] Of these two proposed elements, he thought the lighter to be an all-penetrating, all-pervasive gas, and the slightly heavier one to be a proposed element, coronium.

Mendeleev devoted much study and made important contributions to the determination of the nature of such indefinite compounds as solutions.

In another department of physical chemistry, he investigated the expansion of liquids with heat, and devised a formula similar to Gay-Lussac’s law of the uniformity of the expansion of gases, while in 1861 he anticipated Thomas Andrews’ conception of the critical temperature of gases by defining the absolute boiling-point of a substance as the temperature at which cohesion and heat of vaporization become equal to zero and the liquid changes to vapor, irrespective of the pressure and volume.[52]

Mendeleev is given credit for the introduction of the metric system to the Russian Empire.

He invented pyrocollodion, a kind of smokeless powder based on nitrocellulose. This work had been commissioned by the Russian Navy, which however did not adopt its use. In 1892 Mendeleev organized its manufacture.

Mendeleev studied petroleum origin and concluded hydrocarbons are abiogenic and form deep within the earth – see Abiogenic petroleum origin.

He wrote: «The capital fact to note is that petroleum was born in the depths of the earth, and it is only there that we must seek its origin.» (Dmitri Mendeleev, 1877)[57]

Activities beyond chemistry

Beginning in the 1870s, he published widely beyond chemistry, looking at aspects of Russian industry, and technical issues in agricultural productivity. He explored demographic issues, sponsored studies of the Arctic Sea, tried to measure the efficacy of chemical fertilizers, and promoted the merchant navy.[58] He was especially active in improving the Russian petroleum industry, making detailed comparisons with the more advanced industry in Pennsylvania.[59] Although not well-grounded in economics, he had observed industry throughout his European travels, and in 1891 he helped convince the Ministry of Finance to impose temporary tariffs with the aim of fostering Russian infant industries.[60]

In 1890 he resigned his professorship at St. Petersburg University following a dispute with officials at the Ministry of Education over the treatment of university students.[61] In 1892 he was appointed director of Russia’s Central Bureau of Weights and Measures, and led the way to standardize fundamental prototypes and measurement procedures. He set up an inspection system, and introduced the metric system to Russia.[62][63]

He debated against the scientific claims of spiritualism, arguing that metaphysical idealism was no more than ignorant superstition. He bemoaned the widespread acceptance of spiritualism in Russian culture, and its negative effects on the study of science.[64]

Vodka myth

A very popular Russian story credits Mendeleev with setting the 40% standard strength of vodka. For example, Russian Standard vodka advertises: «In 1894, Dmitri Mendeleev, the greatest scientist in all Russia, received the decree to set the Imperial quality standard for Russian vodka and the ‘Russian Standard’ was born»[65] Others cite «the highest quality of Russian vodka approved by the royal government commission headed by Mendeleev in 1894».[66]

In fact, the 40% standard was already introduced by the Russian government in 1843, when Mendeleev was nine years old.[66] It is true that Mendeleev in 1892 became head of the Archive of Weights and Measures in Saint Petersburg, and evolved it into a government bureau the following year, but that institution was charged with standardising Russian trade weights and measuring instruments, not setting any production quality standards. Also, Mendeleev’s 1865 doctoral dissertation was entitled «A Discourse on the combination of alcohol and water», but it only discussed medical-strength alcohol concentrations over 70%, and he never wrote anything about vodka.[66][67]

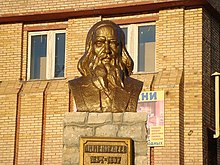

Commemoration

A number of places and objects are associated with the name and achievements of the scientist.

In Saint Petersburg his name was given to D. I. Mendeleev Institute for Metrology, the National Metrology Institute,[68] dealing with establishing and supporting national and worldwide standards for precise measurements. Next to it there is a monument to him that consists of his sitting statue and a depiction of his periodic table on the wall of the establishment.

In the Twelve Collegia building, now being the centre of Saint Petersburg State University and in Mendeleev’s time – Head Pedagogical Institute – there is Dmitry Mendeleev’s Memorial Museum Apartment[69] with his archives. The street in front of these is named after him as Mendeleevskaya liniya (Mendeleev Line).

In Moscow, there is the D. Mendeleyev University of Chemical Technology of Russia.[70]

Mendelevium, which is a synthetic chemical element with the symbol Md (formerly Mv) and the atomic number 101, was named after Mendeleev. It is a metallic radioactive transuranic element in the actinide series, usually synthesized by bombarding einsteinium with alpha particles.

The mineral mendeleevite-Ce, Cs

6(Ce

22Ca

6)(Si

70O

175)(OH,F)

14(H

2O)

21, was named in Mendeleev’s honor in 2010.[71] The related species mendeleevite-Nd, Cs

6[(Nd,REE)

23Ca

7](Si

70O

175)(OH,F)

19(H

2O)

16, was described in 2015.[72]

A large lunar impact crater Mendeleev, that is located on the far side of the Moon, also bears the name of the scientist.

The Russian Academy of Sciences has occasionally awarded a Mendeleev Golden Medal since 1965.[73]

See also

- List of Russian chemists

- Mendeleev’s predicted elements

- Periodic systems of small molecules

Notes

- ^ Before the 1917 reform of Russian orthography, his name was written Дмитрій Ивановичъ Менделѣевъ.

- ^ When the Princeton historian of science Michael Gordin reviewed this article as part of an analysis of the accuracy of Wikipedia for the 14 December 2005 issue of Nature, he cited as one of Wikipedia’s errors that «They say Mendeleev is the 14th child. He is the 14th surviving child of 17 total. 14 is right out.» However in a January 2006 article in The New York Times, it was noted that in Gordin’s own 2004 biography of Mendeleev, he also had the Russian chemist listed as the 17th child, and quoted Gordin’s response to this as being: «That’s curious. I believe that is a typographical error in my book. Mendeleyev was the final child, that is certain, and the number the reliable sources have is 13.» Gordin’s book specifically says that Mendeleev’s mother bore her husband «seventeen children, of whom eight survived to young adulthood», with Mendeleev being the youngest.[24][25]

References

Citations

- ^ a b «Fellows of the Royal Society». London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- ^ «Mendeleev». Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Rao, C N R; Rao, Indumati (2015). Lives and Times of Great Pioneers in Chemistry: (Lavoisier to Sanger). World Scientific. p. 119. ISBN 978-981-4689-07-6.

- ^ a b Maria Mendeleeva (1951). D. I. Mendeleev’s Archive: Autobiographical Writings. Collection of Documents. Volume 1 // Biographical notes about D. I. Mendeleev (written by me – D. Mendeleev), p. 13. – Leningrad: D. I. Mendeleev’s Museum-Archive, 207 pages (in Russian)

- ^ a b Maria Mendeleeva (1951). D. I. Mendeleev’s Archive: Autobiographical Writings. Collection of Documents. Volume 1 // From a family tree documented in 1880 by brother Pavel Ivanovich, p. 11. Leningrad: D. I. Mendeleev’s Museum-Archive, 207 pages (in Russian)

- ^ Dmitriy Mendeleev: A Short CV, and A Story of Life, mendcomm.org

- ^ Удомельские корни Дмитрия Ивановича Менделеева (1834–1907) Archived 8 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, starina.library.tver.ru

- ^ a b Larcher, Alf (21 June 2019). «A mother’s love: Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleeva». Chemistry in Australia magazine. Royal Australian Chemical Institute. ISSN 1839-2539. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Yuri Mandrika (2004). Tobolsk Governorate Vedomosti: Staff and Authors. Anthology of Tobolsk Journalism of the late XIX – early XX centuries in 2 Books // From the interview with Maria Mendeleeva, born Kornilieva, p. 351. Tumen: Mandr i Ka, 624 pages

- ^ Elena Konovalova (2006). A Book of the Tobolsk Governance. 1790–1917. Novosibirsk: State Public Scientific Technological Library, 528-page, p. 15 (in Russian) ISBN 5-94560-116-0

- ^ Yuri Mandrika (2004). Tobolsk Governorate Vedomosti: Staff and Authors. Anthology of Tobolsk Journalism of the late XIX – early XX centuries in 2 Books // The Kornilievs, Tobolsk Manufacturers article by Stepan Mameev, p. 314. – Tumen: Mandr i Ka, 624 pages

- ^ Eugenie Babaev (2009). «Mendelievia. Part 3» article from the Chemistry and Life – 21st Century journal at the MSU Faculty of Chemistry website (in Russian)

- ^ Alexei Storonkin, Roman Dobrotyn (1984). D. I. Mendeleev’s Life and Work Chronicles. Leningrad: Nauka, 539 pages, p. 25

- ^ Nadezhda Gubkina (1908). Family Chronicles. Memories about D. I. Mendeleev. Saint Petersburg, 252 pages

- ^ «Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev comes from indigenous Russian people», p. 5 // Olga Tritogova-Mendeleeva (1947). Mendeleev and His Family. Moscow: Academy of Sciences Publishing House, 104 pages

- ^ Anna Mendeleeva (1928). Mendeleev in Life. Moscow: M. and S. Sabashnikov Publishing House, 194 pages

- ^ Loren R. Graham, Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History, Cambridge University Press (1993), p. 45

- ^ Isaac Asimov, Asimov on Chemistry, Anchoor Books (1975), p. 101

- ^ Leslie Alan Horvitz, Eureka!: Scientific Breakthroughs that Changed the World, John Wiley & Sons (2002), p. 45

- ^ Lennard Bickel, The deadly element: the story of uranium, Stein and Day (1979), p. 22

- ^ Hiebert, Ray Eldon; Hiebert, Roselyn (1975). Atomic Pioneers: From ancient Greece to the 19th century. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Division of Technical Information. p. 25.

- ^ Gordin, Michael D. (2004). A Well-ordered Thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev and the Shadow of the Periodic Table. Basic Books. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-465-02775-0.

Mendeleev seemed to have very few theological commitments. This was not for lack of exposure. His upbringing was actually heavily religious, and his mother – by far the dominating force in his youth – was exceptionally devout. One of his sisters even joined a fanatical religious sect for a time. Despite, or perhaps because of, this background, Mendeleev withheld comment on religious affairs for most of his life, reserving his few words for anti-clerical witticisms … Mendeleev’s son Ivan later vehemently denied claims that his father was devoutly Orthodox: «I have also heard the view of my father’s ‘church religiosity’ – and I must reject this categorically. From his earliest years Father practically split from the church – and if he tolerated certain simple everyday rites, then only as an innocent national tradition, similar to Easter cakes, which he didn’t consider worth fighting against.» … Mendeleev’s opposition to traditional Orthodoxy was not due to either atheism or scientific materialism. Rather, he held to a form of romanticized deism.

- ^ Johnson, George (3 January 2006). «The Nitpicking of the Masses vs. the Authority of the Experts». The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Johnson, George (3 January 2006). «The Nitpicking of the Masses vs. the Authority of the Experts». The New York Times.

- ^ Gordin, Michael (22 December 2005). «Supplementary information to accompany Nature news article «Internet encyclopaedias go head to head» (Nature 438, 900–901; 2005)» (PDF). Blogs.Nature.com. p. 178 – via 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f Heilbron 2003, p. 509.

- ^ «Семья Д.И.Менделеева». Rustest.spb.ru. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ John B. Arden (1998). «Science, Theology and Consciousness», Praeger Frederick A. p. 59: «The initial expression of the commonly used chemical periodic table was reportedly envisioned in a dream. In 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev claimed to have had a dream in which he envisioned a table in which all the chemical elements were arranged according to their atomic weight.»

- ^ John Kotz, Paul Treichel, Gabriela Weaver (2005). «Chemistry and Chemical Reactivity,» Cengage Learning. p. 333

- ^ Gerard I. Nierenberg (1986). «The art of creative thinking», Simon & Schuster, p. 201: Dmitri Mendeleev’s solution for the arrangement of the elements that came to him in a dream.

- ^ Helen Palmer (1998). «Inner Knowing: Consciousness, Creativity, Insight, and Intuition». J.P. Tarcher/Putnam. p. 113: «The sewing machine, for instance, invented by Elias Howe, was developed from material appearing in a dream, as was Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table of elements»

- ^ Simon S. Godfrey (2003). Dreams & Reality. Trafford Publishing. Chapter 2.: «The Russian chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev (1834–1907), described a dream in which he saw the periodic table of elements in its complete form.» ISBN 1-4120-1143-4

- ^ «The Soviet Review Translations» Summer 1967. Vol. VIII, No. 2, M.E. Sharpe, Incorporated, p. 38

- ^ Myron E. Sharpe, (1967). «Soviet Psychology». Volume 5, p. 30.

- ^ «A brief history of the development of the period table», wou.edu

- ^ «Mendeleev and the Periodic Table» Archived 12 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, chemsheets.co.uk

- ^ Seaborg, Glenn T (20 May 1994). «The Periodic Table: Tortuous path to man-made elements». Modern Alchemy: Selected Papers of Glenn T Seaborg. World Scientific. p. 179. ISBN 978-981-4502-99-3. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ Pfennig, Brian W. (3 March 2015). Principles of Inorganic Chemistry. Wiley. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-118-85902-5. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Nye, Mary Jo (2016). «Speaking in Tongues: Science’s centuries-long hunt for a common language». Distillations. 2 (1): 40–43. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Gordin, Michael D. (2015). Scientific Babel: How Science Was Done Before and After Global English. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-00029-9.

- ^ Marshall, James L. Marshall; Marshall, Virginia R. Marshall (2007). «Rediscovery of the elements: The Periodic Table» (PDF). The Hexagon: 23–29. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1956). The discovery of the elements (6th ed.). Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education.

- ^ Scerri, Eric (2019). The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 9780190914363. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). Nature’s Building Blocks ((Hardcover, First Edition) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 521–522. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- ^ Otto Böhtlingk, Panini’s Grammatik: Herausgegeben, Ubersetzt, Erlautert und MIT Verschiedenen Indices Versehe. St. Petersburg, 1839–40.

- ^ Kiparsky, Paul. «Economy and the construction of the Sivasutras». In M.M. Deshpande and S. Bhate (eds.), Paninian Studies. Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1991.

- ^ Kak, Subhash (2004). «Mendeleev and the Periodic Table of Elements». Sandhan. 4 (2): 115–123. arXiv:physics/0411080. Bibcode:2004physics..11080K.

- ^ «The Grammar of the Elements». American Scientist. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ «The Soviet Review Translations Archived 18 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine». Summer 1967. Vol. VIII, No. 2, M.E. Sharpe, Incorporated, p. 39

- ^ «Dmitri Mendeleev». RSC Education. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ «Менделеев обвенчался за взятку». Gazeta.ua. 10 April 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Mendeléeff, Dmitri Ivanovich». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 115.

- ^ John W. Moore; Conrad L. Stanitski; Peter C. Jurs (2007). Chemistry: The Molecular Science, Volume 1. ISBN 978-0-495-11598-4. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ Gribbin, J (2002). The Scientists: A History of Science Told Through the Lives of Its Greatest Inventors. New York: Random House. p. 378. Bibcode:2003shst.book…..G. ISBN 978-0-8129-6788-3.

- ^ Friedman, Robert M. (2001). The politics of excellence: behind the Nobel Prize in science. New York: Times Books. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-0-7167-3103-0.

- ^ Last and Near-Last Words of the Famous, Infamous and Those In-Between By Joseph W. Lewis Jr. M.D.

- ^ Mendeleev, D., 1877. L’Origine du pétrole. Revue Scientifique, 2e Ser., VIII, pp. 409–416.

- ^ Alexander Vucinich, «Mendeleev’s Views on science and society,» ISIS 58:342-51.

- ^ Francis Michael Stackenwalt, «Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev and the Emergence of the Modern Russian Petroleum Industry, 1863–1877.» Ambix 45.2 (1998): 67-84.

- ^ Vincent Barnett, «Catalysing Growth?: Mendeleev and the 1891 Tariff.» in W. Samuels, ed., A Research Annual: Research in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology (2004) Vol. 22 Part 1 pp. 123-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-4154(03)22004-6 Online

- ^ Woods, Gordon (2007). «Mendeleev — The Man and his Legacy».

- ^ Nathan M. Brooks, «Mendeleev and metrology.» Ambix 45.2 (1998): 116-128.

- ^ Michael D. Gordin, «Measure of all the Russias: Metrology and governance in the Russian Empire.» Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 4.4 (2003): 783-815.

- ^ Don C. Rawson, «Mendeleev and the Scientific Claims of Spiritualism.» Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 122.1 (1978): 1-8.

- ^ Sainsburys: Russian Standard Vodka 1L Linked 2014-06-28

- ^ a b c Evseev, Anton (21 November 2011). «Dmitry Mendeleev and 40 degrees of Russian vodka». Science. Moscow: English Pravda.ru. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ Meija, Juris (2009). «Mendeleyev vodka challenge». Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 394 (1): 9–10. doi:10.1007/s00216-009-2710-3. PMID 19288087. S2CID 1123151.

- ^ ВНИИМ Дизайн Груп (13 April 2011). «D. I. Mendeleyev Institute for Metrology». Vniim.ru. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Saint-PetersburgState University. «Museum-Archives n.a. Dmitry Mendeleev – Museums – Culture and Sport – University – Saint-Petersburg state university». Eng.spbu.ru. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ «D. Mendeleyev University of Chemical Technology of Russia». Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ «Mendeleevite-Ce». Mindat.org. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ «Mendeleevite-Nd». Mindat.org. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Academy website

Works cited

- Gordin, Michael (2004). A Well-Ordered Thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev and the Shadow of the Periodic Table. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02775-0.

- Heilbron, John L. (2003). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974376-6.

Further reading

- Mendeleev, Dmitry Ivanovich; Jensen, William B. (2005). Mendeleev on the Periodic Law: Selected Writings, 1869–1905. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-44571-7.

- Strathern, Paul (2001). Mendeleyev’s Dream: The Quest For the Elements. New York: St Martins Press. ISBN 978-0-241-14065-9.

- Mendeleev, Dmitrii Ivanovich (1901). Principles of Chemistry. New York: Collier.

External links

- Works by Dmitri Mendeleev at Project Gutenberg

- Babaev, Eugene V. (February 2009). Dmitriy Mendeleev: A Short CV, and A Story of Life – 2009 biography on the occasion of Mendeleev’s 175th anniversary

- Babaev, Eugene V., Moscow State University. Dmitriy Mendeleev Online

- Original Periodic Table, annotated.

- «Everything in its Place», essay by Oliver Sacks

- Works by or about Dmitri Mendeleev in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Dmitri Mendeleev’s official site

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Week In Review

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history. - Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Britannica Beyond

We’ve created a new place where questions are at the center of learning. Go ahead. Ask. We won’t mind. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

После ознакомления с содержанием Топика ( Сочинения ) по теме «Знаменитые Люди» Советуем каждому из вас обратить внимание на дополнительные материалы. Большинство из наших топиков содержат дополнительные вопросы по тексту и наиболее интересные слова текста. Отвечая на не сложные вопросы по тексту вы сможете максимально осмыслить содержание Топика ( Сочинения ) и если вам необходимо написать собственное Сочинение по теме «Знаменитые Люди» у вас возникнет минимум сложностей.

Если у вас возникают вопросы по прочтению отдельных слов вы можете дважды нажать на непонятное слово и в нижнем левом углу в форме перевода есть отдельная кнопка которая позволит вам услышать непосредственно произношение слова. Или также вы можете пройти к разделу Правила Чтения Английского Языка и найти ответ на возникший вопрос.

Dmitri Mendeleyev

In 1869 the great Russian scientist Dmitri Mendeleyev announced the discovery of the Periodic Law of elements. So science received the key to the secrets of matter.

All the greatest discoveries which have been made since then in the fields of chemistry and physics have been based on this law.

The elements in Mendeleyevs Periodic Table follow one another in the order of their atomic weights. They are arranged in periods and groups.

Mendeleyev s discovery made it possible for the scientists to find 38 new chemical elements to fill the empty spaces left in the Periodic Table.

At the same time they tried to find elements heavier than the last element in the Periodic Table.

In 1955 the American scientist Dr. Glenn Seabord obtained element No 101 and named it Mendelevium in honour of the creator of the Periodic Law.

Дмитрий Менделеев

В 1869 г. великий российский ученый Дмитрий Менделеев объявил об открытии Периодической таблицы элементов. Таким образом наука получила ключ к тайнам бытия.

Все самые большие открытия, которые были сделаны с тех пор в области химии и физики, были основаны на этом законе.

Элементы в Периодической таблице Менделеева следуют друг за другом в соответствии с их атомным весом. Они систематизированы в периоды и группы.

Открытие Менделеева позволило ученым обнаружить 38 новых химических элементов, заполнивших пустые места, оставленные в Периодический таблице.

В то же самое время они попытались найти элементы более тяжелые, чем последний элемент в Периодической таблице.

В 1955 г. американский ученый д-р Гленн Сиборд получил элемент номер 101 и назвал его Менделевиум в честь создателя Периодического Закона.

- Текст

- Веб-страница

Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleyev is a famous Russian chemist. He is best known

for his development of the periodic table of the properties of the chemical elements.

This table displays that elements’ properties are changed periodically when they are

arranged according to atomic weight.

Mendeleyev was born in 1834 in Tobolsk, Siberia. He studied chemistry at the

University of St. Petersburg, and in 1859 he was sent to study at the University of

Heidelberg. Mendeleyev returned to St. Petersburg and became Professor of

Chemistry at the Technical Institute in 1863. He became Professor of General

Chemistry at the University of St. Petersburg in 1866. Mendeleyev was a well-

known teacher, and, because there was no good textbook in chemistry at that time,

he wrote the two-volume “Principles of Chemistry” which became a classic

textbook in chemistry.

In this book Mendeleyev tried to classify the elements according to their

chemical properties. In 1869 he published his first version of his periodic table of

elements. In 1871 he published an improved version of the periodic table, in which

he left gaps for elements that were not known at that time. His table and theories

were proved later when three predicted elements: gallium, germanium, and

scandium were discovered.

Mendeleyev investigated the chemical theory of solution. He found that the

best proportion of alcohol and water in vodka is 40%. He also investigated the

thermal expansion of liquids and the nature of petroleum.

In 1893 he became director of the Bureau of Weights and Measures in St.

Petersburg and held this position until his death in 1907.

0/5000

Результаты (русский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

Дмитрий Иванович Менделеев — знаменитый русский химик. Он является самым известным для его развития свойств химических элементов таблицы Менделеева. Эта таблица показывает, что элементы свойства изменяются периодически, когда они упорядоченные атомный вес. Менделеев родился в 1834 году в Тобольск, Сибирь. Он изучал химию в Университет Санкт-Петербурга и в 1859 году он был направлен на учебу в университете Гейдельберг. Менделеев возвращается в Петербург и стал профессором Химия в техническом институте в 1863 году. Он стал профессором общего Химии в университете Санкт-Петербурге в 1866 году. Менделеев был хорошо-известный учитель, и, потому, что там был не хороший учебник по химии в то время, Он написал в двух томах» принципы химии» ставший классическим Учебник по химии. В этой книге Менделеев пытался классифицировать элементы согласно их химические свойства. В 1869 году он опубликовал свою первую версию его периодической таблицы элементы. В 1871 году он опубликовал усовершенствованный вариант периодической таблицы, в которой Он оставил пробелы для элементов, которые не были известны в то время. Его таблица и теории позже подтвердились, когда три предсказал элементы: галлий, германий, и были обнаружены скандия. Менделеев исследовал химические теории решения. Он обнаружил, что Лучшие пропорции спирта и воды в водке-40%. Он также исследовал тепловое расширение жидкостей и характер нефти. В 1893 году он стал директором бюро мер и весов в Св. Петербург и занимал этот пост до своей смерти в 1907 году.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

Дмитрий Иванович Менделеев является известный русский химик. Он является самым известным

за его развитие периодической таблицы свойств химических элементов.

Эта таблица показывает, что свойства элементов »меняются периодически, когда они

расположены в соответствии с атомным весом.

Менделеев родился в 1834 году в Тобольске, Сибири. Он изучал химию в

университете Санкт-Петербурга, а в 1859 году он был направлен на учебу в университете

Гейдельберга. Менделеев вернулся в Санкт-Петербурге и стал профессором

химии в Техническом институте в 1863 году он стал профессором Генеральной

химии в университете Санкт-Петербурга в 1866 году Менделеев хорошо

учитель известно, и, поскольку не было никакого хороший учебник в области химии в то время,

он написал двухтомный «Основы химии», которая стала классикой

учебник по химии.

В этой книге Менделеев пытался классифицировать элементы в соответствии с их

химическими свойствами. В 1869 году он опубликовал свою первую версию своего периодической таблицы

элементов. В 1871 году он опубликовал улучшенную версию периодической таблицы, в которой

он оставил пробелы для элементов, которые не были известны в то время. Его стол и теории

были доказаны позже, когда три предсказал элементы: галлий, германий, и

скандия были обнаружены.

Менделеева исследовали химический теорию решения. Он обнаружил, что

лучшее соотношение спирта и воды в водке составляет 40%. Он также исследовал

тепловое расширение жидкостей и характер нефти.

В 1893 году он стал директором Бюро мер и весов в Санкт-

Петербурге и занимал эту должность до своей смерти в 1907.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 3:[копия]

Скопировано!

Дмитрий Иванович Московский химико — всемирно известный химик. Он лучше всего известна

для его развития в периодической таблицы свойства химических элементов.

Данная таблица показывает, что элементы» свойства, периодически меняться при их

расположены в соответствии с атомной вес.

Московский химико родился в 1834 году в городе Тобольске, Сибири. Родился на

Университет Санкт-Петербург,И в 1859 году он был отправлен в исследования в университете

Хайдельберга. Термохимические исследования вернулось в Санкт-Петербург и стал профессор

химии в технический институт в 1863 году. Он стал профессор общие

химии в Санкт-Петербурге в 1866 году. Московский химико —

известный учитель, и, поскольку не было учебника по химии в это время,

Он писал в «Принципы химии», который стал классическим

учебник по химии.

В этой книге Николай Кисленко попытался классифицировать элементы в соответствии с их

химические свойства. В 1869 году он опубликовал свою первую версию его периодической таблицы

элементы. В 1871 году он опубликовал усовершенствованный вариант периодической таблицы, в которой

Он оставил для элементов, которые не были известны в то время. Его стола и теории

было доказано позднее, когда три предсказать элементы: галлия, наноструктур и

скандия были обнаружены.

Московский химико расследование химической теории решения. Он пришел к выводу, что

оптимальной доли спирта и воды в водки — 40 %. Он также изучал

температурного расширения жидкостей и характера нефти.

В 1893 году он был назначен директором Бюро Мер и Весов в Сент-

Санкт-Петербург и занимал этот пост до своей смерти в 1907 году.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Другие языки

- English

- Français

- Deutsch

- 中文(简体)

- 中文(繁体)

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Español

- Português

- Русский

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Ελληνικά

- العربية

- Polski

- Català

- ภาษาไทย

- Svenska

- Dansk

- Suomi

- Indonesia

- Tiếng Việt

- Melayu

- Norsk

- Čeština

- فارسی

Поддержка инструмент перевода: Клингонский (pIqaD), Определить язык, азербайджанский, албанский, амхарский, английский, арабский, армянский, африкаанс, баскский, белорусский, бенгальский, бирманский, болгарский, боснийский, валлийский, венгерский, вьетнамский, гавайский, галисийский, греческий, грузинский, гуджарати, датский, зулу, иврит, игбо, идиш, индонезийский, ирландский, исландский, испанский, итальянский, йоруба, казахский, каннада, каталанский, киргизский, китайский, китайский традиционный, корейский, корсиканский, креольский (Гаити), курманджи, кхмерский, кхоса, лаосский, латинский, латышский, литовский, люксембургский, македонский, малагасийский, малайский, малаялам, мальтийский, маори, маратхи, монгольский, немецкий, непальский, нидерландский, норвежский, ория, панджаби, персидский, польский, португальский, пушту, руанда, румынский, русский, самоанский, себуанский, сербский, сесото, сингальский, синдхи, словацкий, словенский, сомалийский, суахили, суданский, таджикский, тайский, тамильский, татарский, телугу, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, уйгурский, украинский, урду, филиппинский, финский, французский, фризский, хауса, хинди, хмонг, хорватский, чева, чешский, шведский, шона, шотландский (гэльский), эсперанто, эстонский, яванский, японский, Язык перевода.

- I hope tomorrow everything will be fine

- and you have good shape.you can be a mod

- Честно говоря я хочу жить в Корее. Это д

- 힝

- pulvus solubilis

- How do you use this word

- Я очень очень очень хочу тебя видеть. sk

- i am going to read

- CINE ESTI?

- Можешь бросить меня ?

- я проснулся,

- ДЛЯ МЕНЯ ГЛАВНОЕ ЛЮБОВЬ ВЕРНОСТЬ ЗАБОТА

- Да, для того чтобы поблагодарить за приг

- i am about to read

- когда ты ложишься спать

- Куда их отправить

- Павел тоже не имеет времени потому что о

- мне нравятся

- Leeren Sie das Gehäuse in regelmä-ßige

- pulvus sterilis

- 힝 ㅠㅠ

- Start a game between 8PM and midnight

- Leeren Sie das Gehäuse in regelmäßigen

- actually i think you might have to verif

Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleyev discovered the periodic law and created the periodic table of elements.

Who Was Dmitri Mendeleyev?

After receiving an education in science in Russia and Germany, Dmitri Mendeleyev became a professor and conducted research in chemistry. Mendeleyev is best known for his discovery of the periodic law, which he introduced in 1869, and for his formulation of the periodic table of elements. He died in St. Petersburg, Russia, on February 2, 1907.

Youth and Education

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleyev was born on February 8, 1834, in the Siberian town of Tobolsk in Russia. His father, Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleyev, went blind around the time his final son was born, and died in 1847. The scientist’s mother, Mariya Dmitriyevna Kornileva, worked as the manager of a glass factory to support herself and her children. When the factory burned down in 1848, the family moved to St. Petersburg.

Mendeleyev attended the Main Pedagogical Institute in St. Petersburg and graduated in 1855. After teaching in the Russian cities of Simferopol and Odessa, he returned to St. Petersburg to earn a master’s degree. Mendeleyev continued his studies abroad, with two years at the University of Heidelberg.

Discovery of the Periodic Law

As a professor, Mendeleyev taught first at the St. Petersburg Technological Institute and then at the University of St. Petersburg, where he remained through 1890. Realizing he was in need of a quality textbook to cover the subject of inorganic chemistry, he put together one of his own, The Principles of Chemistry.

While he was researching and writing that book in the 1860s, Mendeleyev made the discovery that led to his most famous achievement. He noticed certain recurring patterns between different groups of elements and, using existing knowledge of the elements’ chemical and physical properties, he was able to make further connections. He systematically arranged the dozens of known elements by atomic weight in a grid-like diagram; following this system, he could even predict the qualities of still-unknown elements. In 1869, Mendeleyev formally presented his discovery of the periodic law to the Russian Chemical Society.

Scroll to Continue

At first, Mendeleyev’s system had very few supporters in the international scientific community. It gradually gained acceptance over the following two decades with the discoveries of three new elements that possessed the qualities of his earlier predictions. In London in 1889, Mendeleyev presented a summary of his collected research in a lecture titled «The Periodic Law of the Chemical Elements.» His diagram, known as the periodic table of elements, is still used today.

Other Achievements and Activities

Beyond his theoretical work in chemistry, Mendeleyev was known for his more practical scientific studies, often for the benefit of the national economy. He was involved in research on Russian petroleum production, the coal industry and advanced agricultural methods, and he acted as a government consultant on issues ranging from new types of gunpowder to national tariffs.

Mendeleyev remained occupied with scientific activities after leaving his teaching post in 1890. He contributed numerous articles to the new Brockhaus Encyclopedia, and in 1893 he was named director of Russia’s new Central Board of Weights and Measures. He also oversaw multiple reprints of The Principles of Chemistry.

Mendeleyev was married twice, to Feozva Nikitichna Leshcheva in 1862 and to Anna Ivanova Popova in 1882. He had a combined six children from those two marriages.

Later Years and Legacy

In the later years of his career, Mendeleyev was internationally recognized for his contributions to the field of chemistry. He received honorary awards from Oxford and Cambridge, as well as a medal from the Royal Society of London.

Death

Mendeleyev died on February 2, 1907. At his funeral in St. Petersburg, his students carried a large copy of the periodic table of the elements as a tribute to his work.

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

Dmitri Mendeleev (February 8, 1834–February 2, 1907) was a Russian scientist best known for devising the modern periodic table of elements. Mendeleev also made major contributions to other areas of chemistry, metrology (the study of measurements), agriculture, and industry.

Fast Facts: Dmitri Mendeleev

- Known For: Creating the Periodic Law and Periodic Table of the Elements

- Born: February 8, 1834 in Verkhnie Aremzyani, Tobolsk Governorate, Russian Empire

- Parents: Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleev, Maria Dmitrievna Kornilieva

- Died: February 2, 1907 in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire

- Education: Saint Petersburg University

- Published Works: Principles of Chemistry

- Awards and Honors: Davy Medal, ForMemRS

- Spouse(s): Feozva Nikitichna Leshcheva, Anna Ivanovna Popova

- Children: Lyubov, Vladimir, Olga, Anna, Ivan

- Notable Quote: «I saw in a dream a table where all elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper, only in one place did a correction later seem necessary.»

Early Life

Mendeleev was born on February 8, 1834, in Tobolsk, a town in Siberia, Russia. He was the youngest of a large Russian Orthodox Christian family. The exact size of the family is a matter of dispute, with sources putting the number of siblings between 11 and 17. His father was Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleev, a glass manufacturer, and his mother was Dmitrievna Kornilieva.

In the same year that Dmitri was born, his father went blind. He died in 1847. His mother took on the management of the glass factory, but it burned down just a year later. To provide her son with an education, Dmitri’s mother brought him to St. Petersburg and enrolled him in the Main Pedagogical Institute. Soon after, Dmitri’s mother died.

Education

Dmitri graduated from the Institute in 1855 and then went on to earn a masters degree in education. He received a fellowship from the government to continue his studies and moved to the University of Heidelberg in Germany. There, he decided not to work with Bunsen and Erlenmeyer, two distinguished chemists, and instead set up his own laboratory at home. He attended the International Chemistry Congress and met many of Europe’s top chemists.

In 1861, Dmitri went back to St. Petersburg to earn his P.hd. He then became a chemistry professor at the University of St. Petersburg. He continued to teach there until 1890.

The Periodic Table of the Elements

Dmitri found it hard to find a good chemistry textbook for his classes, so he wrote his own. While writing his textbook, Principles of Chemistry, Mendeleev found that if you arrange the elements in order of increasing atomic mass, their chemical properties demonstrated definite trends. He called this discovery the Periodic Law, and stated it in this way: «When the elements are arranged in order of increasing atomic mass, certain sets of properties recur periodically.»

Drawing on his understanding of element characteristics, Mendeleev arranged the known elements in an eight-column grid. Each column represented a set of elements with similar qualities. He called the grid the periodic table of the elements. He presented his grid and his periodic law to the Russian Chemical Society in 1869.

The only real difference between his table and the one we use today is that Mendeleev’s table ordered elements by increasing atomic weight, while the present table is ordered by increasing atomic number.

Mendeleev’s table had blank spaces where he predicted three unknown elements, which turned out to be germanium, gallium, and scandium. Based on the periodic properties of the elements, as shown in the table, Mendeleev predicted properties of eight elements in total, which had not even been discovered.

Writing and Industry

While Mendeleev is remembered for his work in chemistry and the formation of the Russian Chemical Society, he had many other interests. He wrote more than 400 books and articles on topics in popular science and technology. He wrote for ordinary people, and helped create a «library of industrial knowledge.»

He worked for the Russian government and became the director of the Central Bureau of Weights and Measures. He became very interested in the study of measures and did a great deal of research on the subject. Later, he published a journal.

In addition to his interests in chemistry and technology, Mendeleev was interested in helping to develop Russian agriculture and industry. He traveled around the world to learn about the petroleum industry and helped Russia to develop its oil wells. He also worked to develop the Russian coal industry.

Marriage and Children

Mendeleev was married twice. He wed Feozva Nikitchna Leshcheva in 1862, but the couple divorced after 19 years. He married Anna Ivanova Popova the year after the divorce, in 1882. He had a total of six children from these marriages.

Death

In 1907 at age 72, Mendeleev died from the flu. He was living in St. Petersburg at the time. His last words, spoken to his doctor, reportedly were, «Doctor, you have science, I have faith.» This may have been a quote from the famous French writer Jules Verne.

Legacy

Mendeleev, despite his achievements, never won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry. In fact, he was passed over for the honor twice. He was, however, awarded the prestigious Davy Medal (1882) and ForMemRS (1892).

The Periodic Table did not gain acceptance among chemists until Mendeleev’s predictions for new elements were shown to be correct. After gallium was discovered in 1879 and germanium in 1886, it was clear that the table was extremely accurate. By the time of Mendeleev’s death, the Periodic Table of Elements was internationally recognized as one of the most important tools ever created for the study of chemistry.

Sources

- Bensaude-Vincent, Bernadette. “Dmitri Mendeleev.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 25 Feb. 2019.

- Gordon. “Mendeleev — the Man and His Legacy…” Education in Chemistry, 1 Mar. 2007.

- Libretexts. “The Periodic Law.” Chemistry LibreTexts, Libretexts, 24 Apr. 2019.