Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | мета́лл | мета́ллы |

| Р. | мета́лла | мета́ллов |

| Д. | мета́ллу | мета́ллам |

| В. | мета́лл | мета́ллы |

| Тв. | мета́ллом | мета́ллами |

| Пр. | мета́лле | мета́ллах |

ме—та́лл

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -металл- [Тихонов, 1996].

Произношение[править]

- МФА: ед. ч. [mʲɪˈtaɫ] мн. ч. [mʲɪˈtaɫɨ]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- простое вещество (или сплав простых веществ), обладающее твёрдостью, ковкостью, особым блеском, хорошей электропроводностью и теплопроводностью ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

- хим. представитель семейства химических элементов металлы периодической системы химических элементов, в виде простых веществ [1] обладающий характерными свойствами: физическими — высокие тепло- и электропроводность, положительный температурный коэффициент сопротивления, высокая пластичность, ковкость, металлический блеск); химическими — оксид при взаимодействии с водой образует основание ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

- собир. совокупность однотипных изделий из металла [1] ◆ Это связано с пущенными в 2002 году новыми мощностями по производству жести на ММК, а также с введением в апреле 2003 года импортных пошлин на холоднокатаный листовой металл с антикоррозийными покрытиями, поставляемый с Украины. «Внешние факторы благоприятны» // «Металлы Евразии», 2004 г. [НКРЯ]

- муз. то же, что металлический рок ◆ Вчера я поздно лёг, сегодня поздно встал. / Я начал быстро уставать когда слушаю металл. / У-у, наверно, я стал старше. гр. Чайф

- перен. суровость (обычно в сочетаниях типа металл в голосе, металл во взгляде) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

- астрон. любой химический элемент, кроме водорода и гелия ◆ Для шаровых скоплений характерны звёзды с низким содержанием металлов.

Синонимы[править]

- —

- —

- —

- ме́тал

- —

- —

Антонимы[править]

- неметалл

- неметалл

- —

- —

- мягкость, нежность

- —

Гиперонимы[править]

- вещество, материал

- химический элемент

- —

- —

- —

- химический элемент

Гипонимы[править]

- сплавы: альсифер, алюмель, алюцинк, амальгама, баббит, бронза, дюраль (дюралюминий), инвар, ковар, константан, копель, латунь, лигатура, манганин, мельхиор, монель-металл, нейзильбер, никелин, нитинол, нихром, победит, пермаллой, перминвар, платинит, платинородий, припой, силумин, сталь, супермаллой, томпак, фернико, ферромарганец, ферросилиций, ферросплав, феррохром, хромель, чугун, электрон, элинвар; биметалл, триметалл

-

- щелочные металлы: литий, натрий, калий, рубидий, цезий, франций

- щёлочноземельные металлы: кальций, стронций, барий, радий

- переходные металлы:

- благородные металлы: золото, серебро

- платиновые металлы: рутений, родий, палладий, осмий, иридий, платина

- редкоземельные металлы:

- лантаноиды: церий, празеодим, неодим, прометий, самарий, европий, гадолиний, тербий, диспрозий, гольмий, эрбий, тулий, иттербий, лютеций

- прочие: лантан, скандий, иттрий

- актиноиды: торий, протактиний, уран

- трансураны: нептуний, плутоний, америций, кюрий, берклий, калифорний, эйнштейний, фермий, менделевий, нобелий, лоуренсий

- прочие: титан, ванадий, хром, марганец, железо, кобальт, никель, медь, цинк, цирконий, ниобий, молибден, технеций, кадмий, гафний, тантал, вольфрам, рений, ртуть

- благородные металлы: золото, серебро

- полуметаллы: висмут, сурьма, полоний, мышьяк, теллур, германий, олово

- лёгкие металлы: литий, бериллий, натрий, магний, алюминий, калий, кальций, титан, рубидий, стронций, цезий, барий

- тугоплавкие металлы: титан, ванадий, хром, цирконий, ниобий, молибден, гафний, тантал, вольфрам, рений

- радиоактивные металлы: технеций, прометий, франций, радий, полоний, актиний, актиноиды

- прочие: свинец, индий, таллий, галлий

- —

- —

- —

- —

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

| Список всех слов с корнем -металл- | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Этимология[править]

Происходит от лат. metallum «металл», далее из др.-греч. μέταλλον «копь, жила, шахта, рудник». Русск. металл — начиная с эпохи Петра I, заимств. через нем. Меtаll или франц. métal из лат. Использованы данные словаря М. Фасмера. См. Список литературы.

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

- благородный металл

- жёлтый металл

- крылатый металл

- листовой металл

- металл в голосе

- металл платиновой группы

- металлы и сплавы

- презренный металл

- редкий металл

- редкоземельный металл

- скоростной металл

- тяжёлый металл

- цветной металл

- чёрный металл

- щёлочноземельный металл

- щелочной металл

Перевод[править]

| химическое вещество | |

|

| музыкальное направление | |

|

| суровость | |

Анаграммы[править]

- маллет

Библиография[править]

- Новые слова и значения. Словарь-справочник по материалам прессы и литературы 80-х годов / Под ред. Е. А. Левашова. — СПб. : Дмитрий Буланин, 1997.

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Аварский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Башкирский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Казахский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Киргизский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Коми-зырянский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Лакский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Лезгинский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Марийский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Монгольский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Осетинский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Таджикский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Татарский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Удмуртский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Чеченский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Чувашский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Эвенкийский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Якутский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

металл

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- металл ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Из ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

Металл или метал?

Содержание

- 1 Употребление слова МЕТАЛЛ

- 1.1 Примеры предложений

- 2 Употребление слова МЕТАЛ

- 2.1 Примеры предложений

- 3 Ошибочное написание слова

- 4 Заключение

- 5 Правильно/неправильно пишется

Русский язык, конечно, велик и могуч, однако таит в себе множество подводных камней, о которые спотыкаются многие пишущие. Иногда опасности подстерегают даже в самых, казалось бы, простых словах. Одно из них – слово МЕТАЛЛ. Или все-таки МЕТАЛ? Как правильно – с одной Л или с двумя?

И, как это часто бывает в русской орфографии, оба слова правильны, все дело – в смысле полной написанной фразы. В данном случае мы имеем дело с омофонами, то есть со словами, имеющими разное лексическое значение, разными в написании, но которые мы слышим одинаково. Более того, МЕТАЛЛ и МЕТАЛ еще и относятся к разным частям речи.

Употребление слова МЕТАЛЛ

Начнем с существительного. Слово МЕТАЛЛ – с двумя ЛЛ – это существительное второго склонения. И означает оно несколько веществ из химической таблицы Менделеева, объединенных сходными свойствами: блеском, плавкостью, электропроводимостью и так далее.

Происходит слово МЕТАЛЛ, согласно словарю Фасмера, из древнегреческого μέταλλον (читается «металлон»), что в буквальном смысле означает «рудник, шахта». В свою очередь, это слово заимствовали римляне, и оно превратилось в латинское metallum. Следом в очереди – французы, называвшие его métal, потом – немцы (Меtаll). А уже Петр I принес это слово в Россию, где оно трансформировалось в привычный нам МЕТАЛЛ.

Все производные от этого существительного слова также имеют корень «-металл-» и пишутся с двумя ЛЛ, независимо от того, к какой части речи принадлежат:

Металлург (сущ.), металлический (прил.), металлолом (сущ.)

Пожалуй, единственный случай, когда это слово имеет лексическое значение химического элемента, но пишется с одной Л – это музыкальный жанр «хеви-метал»: одно из ответвлений «тяжелого» рока. Но и то одна Л обусловлена тем, что «хеви-метал» происходит от английского написания слова: «metal», сохранившимся в русской транслитерации.

Примеры предложений

- Металлические поверхности сильно нагреваются на солнце.

- В городе шумно отпраздновали День металлурга.

- Два раза в год все старшие классы отправлялись на сбор металлолома.

- — Металл металлу рознь, — заявил дед. – Одни притягивают магниты, другие нет.

- — Как надоел ваш хеви-метал! – вздохнула тетя Лена.

- Груда неиспользованного металла росла и грозила заползти в сарай.

- Металлический блеск ткани создавал ощущение холода и заставлял ежиться.

Употребление слова МЕТАЛ

Второй омоним – слово МЕТАЛ. С одной Л в конце – это глагол несовершенного вида, мужского рода, прошедшего времени, имеющий инфинитив «метать»: «Спортсмен метал копье».

В этом случае все глаголы прошедшего времени от слова «метать» пишутся с одной Л: «метала, метали, метало». Хотя в среднем роде этот глагол чаще всего пишется совершенного вида, с приставками: «разметало, заметало».

Примеры предложений

- Вчера все наши восьмые классы на физкультуре метали мяч.

- В молодости он был спортсменом: метал копье.

- Разозлившись, она метала в стенку все, что под руку попадалось.

- Сено ветром разметало по всему полю.

- Белье беспорядочно заметало по всей улице.

- Павел очень устал: весь день метал сено, чтобы успеть до дождя.

Ошибочное написание слова

Ошибкой будет написать слово МЕТАЛ с одним Л, имея в виду химический элемент и наоборот, написание слова МЕТАЛЛ там, где нужно употребить глагол.

Ошибочно также правописание «митал», «миталл». Проверочного слова тут нет, если есть сомнения – лучше заглянуть в орфографический словарь.

Заключение

Итак, чтобы понять, как правильно пишется МЕТАЛЛ/МЕТАЛ, нужно сначала определить часть речи и запомнить: в существительном – две ЛЛ, в глаголе – одна.

Правильно/неправильно пишется

Металл

Собирать неиспользованный металл

Оценка статьи:

Загрузка…

Iron, shown here as fragments and a 1 cm3 cube, is an example of a chemical element that is a metal.

A metal in the form of a gravy boat made from stainless steel, an alloy largely composed of iron, carbon, and chromium

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον métallon, «mine, quarry, metal») is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typically ductile (can be drawn into wires) and malleable (they can be hammered into thin sheets). These properties are the result of the metallic bond between the atoms or molecules of the metal.

A metal may be a chemical element such as iron; an alloy such as stainless steel; or a molecular compound such as polymeric sulfur nitride.[1]

In physics, a metal is generally regarded as any substance capable of conducting electricity at a temperature of absolute zero.[2] Many elements and compounds that are not normally classified as metals become metallic under high pressures. For example, the nonmetal iodine gradually becomes a metal at a pressure of between 40 and 170 thousand times atmospheric pressure. Equally, some materials regarded as metals can become nonmetals. Sodium, for example, becomes a nonmetal at pressure of just under two million times atmospheric pressure.

In chemistry, two elements that would otherwise qualify (in physics) as brittle metals—arsenic and antimony—are commonly instead recognised as metalloids due to their chemistry (predominantly non-metallic for arsenic, and balanced between metallicity and nonmetallicity for antimony). Around 95 of the 118 elements in the periodic table are metals (or are likely to be such). The number is inexact as the boundaries between metals, nonmetals, and metalloids fluctuate slightly due to a lack of universally accepted definitions of the categories involved.

In astrophysics the term «metal» is cast more widely to refer to all chemical elements in a star that are heavier than helium, and not just traditional metals. In this sense the first four «metals» collecting in stellar cores through nucleosynthesis are carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and neon, all of which are strictly non-metals in chemistry. A star fuses lighter atoms, mostly hydrogen and helium, into heavier atoms over its lifetime. Used in that sense, the metallicity of an astronomical object is the proportion of its matter made up of the heavier chemical elements.[3][4]

Metals, as chemical elements, comprise 25% of the Earth’s crust and are present in many aspects of modern life. The strength and resilience of some metals has led to their frequent use in, for example, high-rise building and bridge construction, as well as most vehicles, many home appliances, tools, pipes, and railroad tracks. Precious metals were historically used as coinage, but in the modern era, coinage metals have extended to at least 23 of the chemical elements.[5]

The history of refined metals is thought to begin with the use of copper about 11,000 years ago. Gold, silver, iron (as meteoric iron), lead, and brass were likewise in use before the first known appearance of bronze in the fifth millennium BCE. Subsequent developments include the production of early forms of steel; the discovery of sodium—the first light metal—in 1809; the rise of modern alloy steels; and, since the end of World War II, the development of more sophisticated alloys.

Properties

Form and structure

Metals are shiny and lustrous, at least when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured. Sheets of metal thicker than a few micrometres appear opaque, but gold leaf transmits green light.

The solid or liquid state of metals largely originates in the capacity of the metal atoms involved to readily lose their outer shell electrons. Broadly, the forces holding an individual atom’s outer shell electrons in place are weaker than the attractive forces on the same electrons arising from interactions between the atoms in the solid or liquid metal. The electrons involved become delocalised and the atomic structure of a metal can effectively be visualised as a collection of atoms embedded in a cloud of relatively mobile electrons. This type of interaction is called a metallic bond.[6] The strength of metallic bonds for different elemental metals reaches a maximum around the center of the transition metal series, as these elements have large numbers of delocalized electrons.[n 1]

Although most elemental metals have higher densities than most nonmetals,[6] there is a wide variation in their densities, lithium being the least dense (0.534 g/cm3) and osmium (22.59 g/cm3) the most dense. (Some of the 6d transition metals are expected to be denser than osmium, but predictions on their densities vary widely in the literature, and in any case their known isotopes are too unstable for bulk production to be possible.) Magnesium, aluminium and titanium are light metals of significant commercial importance. Their respective densities of 1.7, 2.7, and 4.5 g/cm3 can be compared to those of the older structural metals, like iron at 7.9 and copper at 8.9 g/cm3. An iron ball would thus weigh about as much as three aluminum balls of equal volume.

A metal rod with a hot-worked eyelet. Hot-working exploits the capacity of metal to be plastically deformed.

Metals are typically malleable and ductile, deforming under stress without cleaving.[6] The nondirectional nature of metallic bonding is thought to contribute significantly to the ductility of most metallic solids. In contrast, in an ionic compound like table salt, when the planes of an ionic bond slide past one another, the resultant change in location shifts ions of the same charge closer, resulting in the cleavage of the crystal. Such a shift is not observed in a covalently bonded crystal, such as a diamond, where fracture and crystal fragmentation occurs.[7] Reversible elastic deformation in metals can be described by Hooke’s Law for restoring forces, where the stress is linearly proportional to the strain.

Heat or forces larger than a metal’s elastic limit may cause a permanent (irreversible) deformation, known as plastic deformation or plasticity. An applied force may be a tensile (pulling) force, a compressive (pushing) force, or a shear, bending, or torsion (twisting) force. A temperature change may affect the movement or displacement of structural defects in the metal such as grain boundaries, point vacancies, line and screw dislocations, stacking faults and twins in both crystalline and non-crystalline metals. Internal slip, creep, and metal fatigue may ensue.

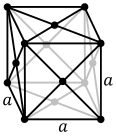

The atoms of metallic substances are typically arranged in one of three common crystal structures, namely body-centered cubic (bcc), face-centered cubic (fcc), and hexagonal close-packed (hcp). In bcc, each atom is positioned at the center of a cube of eight others. In fcc and hcp, each atom is surrounded by twelve others, but the stacking of the layers differs. Some metals adopt different structures depending on the temperature.[8]

-

Body-centered cubic crystal structure, with a 2-atom unit cell, as found in e.g. chromium, iron, and tungsten

-

Face-centered cubic crystal structure, with a 4-atom unit cell, as found in e.g. aluminum, copper, and gold

-

Hexagonal close-packed crystal structure, with a 6-atom unit cell, as found in e.g. titanium, cobalt, and zinc

The unit cell for each crystal structure is the smallest group of atoms which has the overall symmetry of the crystal, and from which the entire crystalline lattice can be built up by repetition in three dimensions. In the case of the body-centered cubic crystal structure shown above, the unit cell is made up of the central atom plus one-eight of each of the eight corner atoms.

Electrical and thermal

The electronic structure of metals means they are relatively good conductors of electricity. Electrons in matter can only have fixed rather than variable energy levels, and in a metal the energy levels of the electrons in its electron cloud, at least to some degree, correspond to the energy levels at which electrical conduction can occur. In a semiconductor like silicon or a nonmetal like sulfur there is an energy gap between the electrons in the substance and the energy level at which electrical conduction can occur. Consequently, semiconductors and nonmetals are relatively poor conductors.

The elemental metals have electrical conductivity values of from 6.9 × 103 S/cm for manganese to 6.3 × 105 S/cm for silver. In contrast, a semiconducting metalloid such as boron has an electrical conductivity 1.5 × 10−6 S/cm. With one exception, metallic elements reduce their electrical conductivity when heated. Plutonium increases its electrical conductivity when heated in the temperature range of around −175 to +125 °C.

Metals are relatively good conductors of heat. The electrons in a metal’s electron cloud are highly mobile and easily able to pass on heat-induced vibrational energy.

The contribution of a metal’s electrons to its heat capacity and thermal conductivity, and the electrical conductivity of the metal itself can be calculated from the free electron model. However, this does not take into account the detailed structure of the metal’s ion lattice. Taking into account the positive potential caused by the arrangement of the ion cores enables consideration of the electronic band structure and binding energy of a metal. Various mathematical models are applicable, the simplest being the nearly free electron model.

Chemical

Metals are usually inclined to form cations through electron loss.[6] Most will react with oxygen in the air to form oxides over various timescales (potassium burns in seconds while iron rusts over years). Some others, like palladium, platinum, and gold, do not react with the atmosphere at all. The oxides of metals are generally basic, as opposed to those of nonmetals, which are acidic or neutral. Exceptions are largely oxides with very high oxidation states such as CrO3, Mn2O7, and OsO4, which have strictly acidic reactions.

Painting, anodizing, or plating metals are good ways to prevent their corrosion. However, a more reactive metal in the electrochemical series must be chosen for coating, especially when chipping of the coating is expected. Water and the two metals form an electrochemical cell and, if the coating is less reactive than the underlying metal, the coating actually promotes corrosion.

Periodic table distribution

The elements that form metallic structures under ordinary conditions are shown in yellow on the periodic table below. The remaining elements either form giant covalent structures (light blue), molecular covalent structures (dark blue), or remain as single atoms (violet).[9] Astatine (At), francium (Fr), and the elements from fermium (Fm) onwards are shown in gray because they are extremely radioactive and have never been produced in bulk. Theoretical and experimental evidence suggests that almost all these uninvestigated elements should be metals,[10] though there is some doubt for oganesson (Og).[11]

Bonding of simple substances in the periodic table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||||||

| Group → | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↓ Period | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn |

| 7 | Fr | Ra | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og |

The situation can change with pressure: at extremely high pressures, all elements (and indeed all substances) are expected to metallize.[10] Arsenic (As) has both a stable metallic allotrope and a metastable semiconducting allotrope at standard conditions.

Elements near the border between metals and nonmetals often have intermediate chemical behavior. As such, a category of metalloids is often used for such in-between elements, but there is no consensus in the literature as to which elements should qualify.[12]

Alloys

An alloy is a substance having metallic properties and which is composed of two or more elements at least one of which is a metal. An alloy may have a variable or fixed composition. For example, gold and silver form an alloy in which the proportions of gold or silver can be freely adjusted; titanium and silicon form an alloy Ti2Si in which the ratio of the two components is fixed (also known as an intermetallic compound).

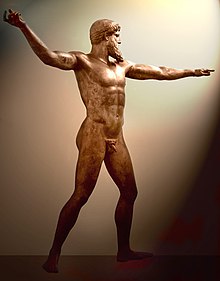

A sculpture cast in nickel silver—an alloy of copper, nickel, and zinc that looks like silver

Most pure metals are either too soft, brittle, or chemically reactive for practical use. Combining different ratios of metals as alloys modifies the properties of pure metals to produce desirable characteristics. The aim of making alloys is generally to make them less brittle, harder, resistant to corrosion, or have a more desirable color and luster. Of all the metallic alloys in use today, the alloys of iron (steel, stainless steel, cast iron, tool steel, alloy steel) make up the largest proportion both by quantity and commercial value. Iron alloyed with various proportions of carbon gives low-, mid-, and high-carbon steels, with increasing carbon levels reducing ductility and toughness. The addition of silicon will produce cast irons, while the addition of chromium, nickel, and molybdenum to carbon steels (more than 10%) results in stainless steels.

Other significant metallic alloys are those of aluminum, titanium, copper, and magnesium. Copper alloys have been known since prehistory—bronze gave the Bronze Age its name—and have many applications today, most importantly in electrical wiring. The alloys of the other three metals have been developed relatively recently; due to their chemical reactivity they require electrolytic extraction processes. The alloys of aluminum, titanium, and magnesium are valued for their high strength-to-weight ratios; magnesium can also provide electromagnetic shielding.[citation needed] These materials are ideal for situations where high strength-to-weight ratio is more important than material cost, such as in aerospace and some automotive applications.

Alloys specially designed for highly demanding applications, such as jet engines, may contain more than ten elements.

Categories

Metals can be categorised according to their physical or chemical properties. Categories described in the subsections below include ferrous and non-ferrous metals; brittle metals and refractory metals; white metals; heavy and light metals; and base, noble, and precious metals. The Metallic elements table in this section categorises the elemental metals on the basis of their chemical properties into alkali and alkaline earth metals; transition and post-transition metals; and lanthanides and actinides. Other categories are possible, depending on the criteria for inclusion. For example, the ferromagnetic metals—those metals that are magnetic at room temperature—are iron, cobalt, and nickel.

Ferrous and non-ferrous metals

The term «ferrous» is derived from the Latin word meaning «containing iron». This can include pure iron, such as wrought iron, or an alloy such as steel. Ferrous metals are often magnetic, but not exclusively. Non-ferrous metals and alloys lack appreciable amounts of iron.

Brittle metal

While nearly all metals are malleable or ductile, a few—beryllium, chromium, manganese, gallium, and bismuth—are brittle.[13] Arsenic and antimony, if admitted as metals, are brittle. Low values of the ratio of bulk elastic modulus to shear modulus (Pugh’s criterion) are indicative of intrinsic brittleness.

Refractory metal

In materials science, metallurgy, and engineering, a refractory metal is a metal that is extraordinarily resistant to heat and wear. Which metals belong to this category varies; the most common definition includes niobium, molybdenum, tantalum, tungsten, and rhenium. They all have melting points above 2000 °C, and a high hardness at room temperature.

-

Niobium crystals and a 1 cm3 anodized niobium cube for comparison

-

Molybdenum crystals and a 1 cm3 molybdenum cube for comparison

-

Tantalum single crystal, some crystalline fragments, and a 1 cm3 tantalum cube for comparison

-

Tungsten rods with evaporated crystals, partially oxidized with colorful tarnish, and a 1 cm3 tungsten cube for comparison

-

Rhenium single crystal, a remelted bar, and a 1 cm3 rhenium cube for comparison

White metal

A white metal is any of range of white-coloured metals (or their alloys) with relatively low melting points. Such metals include zinc, cadmium, tin, antimony (here counted as a metal), lead, and bismuth, some of which are quite toxic. In Britain, the fine art trade uses the term «white metal» in auction catalogues to describe foreign silver items which do not carry British Assay Office marks, but which are nonetheless understood to be silver and are priced accordingly.

Heavy and light metals

A heavy metal is any relatively dense metal or metalloid.[14] More specific definitions have been proposed, but none have obtained widespread acceptance. Some heavy metals have niche uses, or are notably toxic; some are essential in trace amounts. All other metals are light metals.

Base, noble, and precious metals

In chemistry, the term base metal is used informally to refer to a metal that is easily oxidized or corroded, such as reacting easily with dilute hydrochloric acid (HCl) to form a metal chloride and hydrogen. Examples include iron, nickel, lead, and zinc. Copper is considered a base metal as it is oxidized relatively easily, although it does not react with HCl.

Rhodium, a noble metal, shown here as 1 g of powder, a 1 g pressed cylinder, and a 1 g pellet

The term noble metal is commonly used in opposition to base metal. Noble metals are resistant to corrosion or oxidation,[15] unlike most base metals. They tend to be precious metals, often due to perceived rarity. Examples include gold, platinum, silver, rhodium, iridium, and palladium.

In alchemy and numismatics, the term base metal is contrasted with precious metal, that is, those of high economic value.[16]

A longtime goal of the alchemists was the transmutation of base metals into precious metals including such coinage metals as silver and gold. Most coins today are made of base metals with low intrinsic value; in the past, coins frequently derived their value primarily from their precious metal content.

Chemically, the precious metals (like the noble metals) are less reactive than most elements, have high luster and high electrical conductivity. Historically, precious metals were important as currency, but are now regarded mainly as investment and industrial commodities. Gold, silver, platinum, and palladium each have an ISO 4217 currency code. The best-known precious metals are gold and silver. While both have industrial uses, they are better known for their uses in art, jewelry, and coinage. Other precious metals include the platinum group metals: ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum, of which platinum is the most widely traded.

The demand for precious metals is driven not only by their practical use, but also by their role as investments and a store of value.[17] Palladium and platinum, as of fall 2018, were valued at about three quarters the price of gold. Silver is substantially less expensive than these metals, but is often traditionally considered a precious metal in light of its role in coinage and jewelry.

Valve metals

In electrochemistry, a valve metal is a metal which passes current in only one direction.

Lifecycle

Formation

|

Metals in the Earth’s crust:

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abundance and main occurrence or source, by weight[n 2] | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| 1 | H | He | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | |||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | |||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | |

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | ||||

| 7 | |||||||||||||||||||

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | |||||||

| Th | U | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Most abundant (up to 82000 ppm) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Abundant (100–999 ppm) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Uncommon (1–99 ppm) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Rare (0.01–0.99 ppm) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Very rare (0.0001–0.0099 ppm) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Metals left of the dividing line occur (or are sourced) mainly as lithophiles; those to the right, as chalcophiles except gold (a siderophile) and tin (a lithophile). |

- This sub-section deals with the formation of periodic table elemental metals since these form the basis of metallic materials, as defined in this article.

Metals up to the vicinity of iron (in the periodic table) are largely made via stellar nucleosynthesis. In this process, lighter elements from hydrogen to silicon undergo successive fusion reactions inside stars, releasing light and heat and forming heavier elements with higher atomic numbers.[18]

Heavier metals are not usually formed this way since fusion reactions involving such nuclei would consume rather than release energy.[19] Rather, they are largely synthesised (from elements with a lower atomic number) by neutron capture, with the two main modes of this repetitive capture being the s-process and the r-process. In the s-process («s» stands for «slow»), singular captures are separated by years or decades, allowing the less stable nuclei to beta decay,[20] while in the r-process («rapid»), captures happen faster than nuclei can decay. Therefore, the s-process takes a more-or-less clear path: for example, stable cadmium-110 nuclei are successively bombarded by free neutrons inside a star until they form cadmium-115 nuclei which are unstable and decay to form indium-115 (which is nearly stable, with a half-life 30000 times the age of the universe). These nuclei capture neutrons and form indium-116, which is unstable, and decays to form tin-116, and so on.[18][21][n 3] In contrast, there is no such path in the r-process. The s-process stops at bismuth due to the short half-lives of the next two elements, polonium and astatine, which decay to bismuth or lead. The r-process is so fast it can skip this zone of instability and go on to create heavier elements such as thorium and uranium.[23]

Metals condense in planets as a result of stellar evolution and destruction processes. Stars lose much of their mass when it is ejected late in their lifetimes, and sometimes thereafter as a result of a neutron star merger,[24][n 4] thereby increasing the abundance of elements heavier than helium in the interstellar medium. When gravitational attraction causes this matter to coalesce and collapse new stars and planets are formed.[26]

Abundance and occurrence

A sample of diaspore, an aluminum oxide hydroxide mineral, α-AlO(OH)

The Earth’s crust is made of approximately 25% of metals by weight, of which 80% are light metals such as sodium, magnesium, and aluminium. Nonmetals (~75%) make up the rest of the crust. Despite the overall scarcity of some heavier metals such as copper, they can become concentrated in economically extractable quantities as a result of mountain building, erosion, or other geological processes.

Metals are primarily found as lithophiles (rock-loving) or chalcophiles (ore-loving). Lithophile metals are mainly the s-block elements, the more reactive of the d-block elements, and the f-block elements. They have a strong affinity for oxygen and mostly exist as relatively low-density silicate minerals. Chalcophile metals are mainly the less reactive d-block elements, and the period 4–6 p-block metals. They are usually found in (insoluble) sulfide minerals. Being denser than the lithophiles, hence sinking lower into the crust at the time of its solidification, the chalcophiles tend to be less abundant than the lithophiles.

On the other hand, gold is a siderophile, or iron-loving element. It does not readily form compounds with either oxygen or sulfur. At the time of the Earth’s formation, and as the most noble (inert) of metals, gold sank into the core due to its tendency to form high-density metallic alloys. Consequently, it is a relatively rare metal. Some other (less) noble metals—molybdenum, rhenium, the platinum group metals (ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum), germanium, and tin—can be counted as siderophiles but only in terms of their primary occurrence in the Earth (core, mantle, and crust), rather the crust. These metals otherwise occur in the crust, in small quantities, chiefly as chalcophiles (less so in their native form).[n 5]

The rotating fluid outer core of the Earth’s interior, which is composed mostly of iron, is thought to be the source of Earth’s protective magnetic field.[n 6] The core lies above Earth’s solid inner core and below its mantle. If it could be rearranged into a column having a 5 m2 (54 sq ft) footprint it would have a height of nearly 700 light years. The magnetic field shields the Earth from the charged particles of the solar wind, and cosmic rays that would otherwise strip away the upper atmosphere (including the ozone layer that limits the transmission of ultraviolet radiation).

Metals are often extracted from the Earth by means of mining ores that are rich sources of the requisite elements, such as bauxite. Ore is located by prospecting techniques, followed by the exploration and examination of deposits. Mineral sources are generally divided into surface mines, which are mined by excavation using heavy equipment, and subsurface mines. In some cases, the sale price of the metal(s) involved make it economically feasible to mine lower concentration sources.

Once the ore is mined, the metals must be extracted, usually by chemical or electrolytic reduction. Pyrometallurgy uses high temperatures to convert ore into raw metals, while hydrometallurgy employs aqueous chemistry for the same purpose. The methods used depend on the metal and their contaminants.

When a metal ore is an ionic compound of that metal and a non-metal, the ore must usually be smelted—heated with a reducing agent—to extract the pure metal. Many common metals, such as iron, are smelted using carbon as a reducing agent. Some metals, such as aluminum and sodium, have no commercially practical reducing agent, and are extracted using electrolysis instead.[27][28]

Sulfide ores are not reduced directly to the metal but are roasted in air to convert them to oxides.

Uses

Metals are present in nearly all aspects of modern life. Iron, a heavy metal, may be the most common as it accounts for 90% of all refined metals; aluminum, a light metal, is the next most commonly refined metal. Pure iron may be the cheapest metallic element of all at cost of about US$0.07 per gram. Its ores are widespread; it is easy to refine; and the technology involved has been developed over hundreds of years. Cast iron is even cheaper, at a fraction of US$0.01 per gram, because there is no need for subsequent purification. Platinum, at a cost of about $27 per gram, may be the most ubiquitous given its very high melting point, resistance to corrosion, electrical conductivity, and durability. It is said to be found in, or used to produce, 20% of all consumer goods. Polonium is likely to be the most expensive metal that is traded, at a notional cost of about $100,000,000 per gram,[citation needed] due to its scarcity and micro-scale production.

Some metals and metal alloys possess high structural strength per unit mass, making them useful materials for carrying large loads or resisting impact damage. Metal alloys can be engineered to have high resistance to shear, torque, and deformation. However the same metal can also be vulnerable to fatigue damage through repeated use or from sudden stress failure when a load capacity is exceeded. The strength and resilience of metals has led to their frequent use in high-rise building and bridge construction, as well as most vehicles, many appliances, tools, pipes, and railroad tracks.

Metals are good conductors, making them valuable in electrical appliances and for carrying an electric current over a distance with little energy lost. Electrical power grids rely on metal cables to distribute electricity. Home electrical systems, for the most part, are wired with copper wire for its good conducting properties.

The thermal conductivity of metals is useful for containers to heat materials over a flame. Metals are also used for heat sinks to protect sensitive equipment from overheating.

The high reflectivity of some metals enables their use in mirrors, including precision astronomical instruments, and adds to the aesthetics of metallic jewelry.

Some metals have specialized uses; mercury is a liquid at room temperature and is used in switches to complete a circuit when it flows over the switch contacts. Radioactive metals such as uranium and plutonium are fuel for nuclear power plants, which produce energy via nuclear fission. Shape-memory alloys are used for applications such as pipes, fasteners, and vascular stents.

Metals can be doped with foreign molecules—organic, inorganic, biological, and polymers. This doping entails the metal with new properties that are induced by the guest molecules. Applications in catalysis, medicine, electrochemical cells, corrosion and more have been developed.[29]

Recycling

A pile of compacted steel scraps, ready for recycling

Demand for metals is closely linked to economic growth given their use in infrastructure, construction, manufacturing, and consumer goods. During the 20th century, the variety of metals used in society grew rapidly. Today, the development of major nations, such as China and India, and technological advances, are fuelling ever more demand. The result is that mining activities are expanding, and more and more of the world’s metal stocks are above ground in use, rather than below ground as unused reserves. An example is the in-use stock of copper. Between 1932 and 1999, copper in use in the U.S. rose from 73 g to 238 g per person.[30]

Metals are inherently recyclable, so in principle, can be used over and over again, minimizing these negative environmental impacts and saving energy. For example, 95% of the energy used to make aluminum from bauxite ore is saved by using recycled material.[31]

Globally, metal recycling is generally low. In 2010, the International Resource Panel, hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme published reports on metal stocks that exist within society[32] and their recycling rates.[30] The authors of the report observed that the metal stocks in society can serve as huge mines above ground. They warned that the recycling rates of some rare metals used in applications such as mobile phones, battery packs for hybrid cars and fuel cells are so low that unless future end-of-life recycling rates are dramatically stepped up these critical metals will become unavailable for use in modern technology.

Biological interactions

The role of metallic elements in the evolution of cell biochemistry has been reviewed, including a detailed section on the role of calcium in redox enzymes.[33]

One or more of the elements iron, cobalt, nickel, copper, and zinc are essential to all higher forms of life. Molybdenum is an essential component of vitamin B12. Compounds of all other transition elements and post-transition elements are toxic to a greater or lesser extent, with few exceptions such as certain compounds of antimony and tin. Potential sources of metal poisoning include mining, tailings, industrial wastes, agricultural runoff, occupational exposure, paints, and treated timber.

History

Prehistory

Copper, which occurs in native form, may have been the first metal discovered given its distinctive appearance, heaviness, and malleability compared to other stones or pebbles. Gold, silver, and iron (as meteoric iron), and lead were likewise discovered in prehistory. Forms of brass, an alloy of copper and zinc made by concurrently smelting the ores of these metals, originate from this period (although pure zinc was not isolated until the 13th century). The malleability of the solid metals led to the first attempts to craft metal ornaments, tools, and weapons. Meteoric iron containing nickel was discovered from time to time and, in some respects this was superior to any industrial steel manufactured up to the 1880s when alloy steels become prominent.[34]

-

-

Gold crystals

-

Crystalline silver

-

A slice of meteoric iron

-

-

A brass weight (35 g)

Antiquity

The discovery of bronze (an alloy of copper with arsenic or tin) enabled people to create metal objects which were harder and more durable than previously possible. Bronze tools, weapons, armor, and building materials such as decorative tiles were harder and more durable than their stone and copper («Chalcolithic») predecessors. Initially, bronze was made of copper and arsenic (forming arsenic bronze) by smelting naturally or artificially mixed ores of copper and arsenic.[35] The earliest artifacts so far known come from the Iranian plateau in the fifth millennium BCE.[36] It was only later that tin was used, becoming the major non-copper ingredient of bronze in the late third millennium BCE.[37] Pure tin itself was first isolated in 1800 BCE by Chinese and Japanese metalworkers.

Mercury was known to ancient Chinese and Indians before 2000 BCE, and found in Egyptian tombs dating from 1500 BCE.

The earliest known production of steel, an iron-carbon alloy, is seen in pieces of ironware excavated from an archaeological site in Anatolia (Kaman-Kalehöyük) and are nearly 4,000 years old, dating from 1800 BCE.[38][39]

From about 500 BCE sword-makers of Toledo, Spain, were making early forms of alloy steel by adding a mineral called wolframite, which contained tungsten and manganese, to iron ore (and carbon). The resulting Toledo steel came to the attention of Rome when used by Hannibal in the Punic Wars. It soon became the basis for the weaponry of Roman legions; their swords were said to have been «so keen that there is no helmet which cannot be cut through by them.»[citation needed][n 8]

In pre-Columbian America, objects made of tumbaga, an alloy of copper and gold, started being produced in Panama and Costa Rica between 300 and 500 CE. Small metal sculptures were common and an extensive range of tumbaga (and gold) ornaments comprised the usual regalia of persons of high status.

At around the same time indigenous Ecuadorians were combining gold with a naturally-occurring platinum alloy containing small amounts of palladium, rhodium, and iridium, to produce miniatures and masks composed of a white gold-platinum alloy. The metal workers involved heated gold with grains of the platinum alloy until the gold melted at which point the platinum group metals became bound within the gold. After cooling, the resulting conglomeration was hammered and reheated repeatedly until it became as homogenous as if all of the metals concerned had been melted together (attaining the melting points of the platinum group metals concerned was beyond the technology of the day).[40][n 9]

-

A droplet of solidified molten tin

-

-

Electrum, a natural alloy of silver and gold, was often used for making coins. Shown is the Roman god Apollo, and on the obverse, a Delphi tripod (circa 310–305 BCE).

-

A plate made of pewter, an alloy of 85–99% tin and (usually) copper. Pewter was first used around the beginning of the Bronze Age in the Near East.

-

A pectoral (ornamental breastplate) made of tumbaga, an alloy of gold and copper

Middle Ages

Gold is for the mistress—silver for the maid—

Copper for the craftsman cunning at his trade.

«Good!» said the Baron, sitting in his hall,

«But Iron—Cold Iron—is master of them all.»

from Cold Iron by Rudyard Kipling[41]

Arabic and medieval alchemists believed that all metals and matter were composed of the principle of sulfur, the father of all metals and carrying the combustible property, and the principle of mercury, the mother of all metals[n 10] and carrier of the liquidity, fusibility, and volatility properties. These principles were not necessarily the common substances sulfur and mercury found in most laboratories. This theory reinforced the belief that all metals were destined to become gold in the bowels of the earth through the proper combinations of heat, digestion, time, and elimination of contaminants, all of which could be developed and hastened through the knowledge and methods of alchemy.[n 11]

Arsenic, zinc, antimony, and bismuth became known, although these were at first called semimetals or bastard metals on account of their immalleability. All four may have been used incidentally in earlier times without recognising their nature. Albertus Magnus is believed to have been the first to isolate arsenic from a compound in 1250, by heating soap together with arsenic trisulfide. Metallic zinc, which is brittle if impure, was isolated in India by 1300 AD. The first description of a procedure for isolating antimony is in the 1540 book De la pirotechnia by Vannoccio Biringuccio. Bismuth was described by Agricola in De Natura Fossilium (c. 1546); it had been confused in early times with tin and lead because of its resemblance to those elements.

-

Arsenic, sealed in a container to prevent tarnishing

-

Zinc fragments and a 1 cm3 cube

-

Antimony, showing its brilliant lustre

-

Bismuth in crystalline form, with a very thin oxidation layer, and a 1 cm3 bismuth cube

The Renaissance

Ultrapure cerium under argon, 1.5 gm

The first systematic text on the arts of mining and metallurgy was De la Pirotechnia (1540) by Vannoccio Biringuccio, which treats the examination, fusion, and working of metals.

Sixteen years later, Georgius Agricola published De Re Metallica in 1556, a clear and complete account of the profession of mining, metallurgy, and the accessory arts and sciences, as well as qualifying as the greatest treatise on the chemical industry through the sixteenth century.

He gave the following description of a metal in his De Natura Fossilium (1546):

Metal is a mineral body, by nature either liquid or somewhat hard. The latter may be melted by the heat of the fire, but when it has cooled down again and lost all heat, it becomes hard again and resumes its proper form. In this respect it differs from the stone which melts in the fire, for although the latter regain its hardness, yet it loses its pristine form and properties.

Traditionally there are six different kinds of metals, namely gold, silver, copper, iron, tin, and lead. There are really others, for quicksilver is a metal, although the Alchemists disagree with us on this subject, and bismuth is also. The ancient Greek writers seem to have been ignorant of bismuth, wherefore Ammonius rightly states that there are many species of metals, animals, and plants which are unknown to us. Stibium when smelted in the crucible and refined has as much right to be regarded as a proper metal as is accorded to lead by writers. If when smelted, a certain portion be added to tin, a bookseller’s alloy is produced from which the type is made that is used by those who print books on paper.

Each metal has its own form which it preserves when separated from those metals which were mixed with it. Therefore neither electrum nor Stannum [not meaning our tin] is of itself a real metal, but rather an alloy of two metals. Electrum is an alloy of gold and silver, Stannum of lead and silver. And yet if silver be parted from the electrum, then gold remains and not electrum; if silver be taken away from Stannum, then lead remains and not Stannum.

Whether brass, however, is found as a native metal or not, cannot be ascertained with any surety. We only know of the artificial brass, which consists of copper tinted with the colour of the mineral calamine. And yet if any should be dug up, it would be a proper metal. Black and white copper seem to be different from the red kind.

Metal, therefore, is by nature either solid, as I have stated, or fluid, as in the unique case of quicksilver.

But enough now concerning the simple kinds.[42]

Platinum, the third precious metal after gold and silver, was discovered in Ecuador during the period 1736 to 1744, by the Spanish astronomer Antonio de Ulloa and his colleague the mathematician Jorge Juan y Santacilia. Ulloa was the first person to write a scientific description of the metal, in 1748.

In 1789, the German chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth isolated an oxide of uranium, which he thought was the metal itself. Klaproth was subsequently credited as the discoverer of uranium. It was not until 1841, that the French chemist Eugène-Melchior Péligot, prepared the first sample of uranium metal. Henri Becquerel subsequently discovered radioactivity in 1896 by using uranium.

In the 1790s, Joseph Priestley and the Dutch chemist Martinus van Marum observed the transformative action of metal surfaces on the dehydrogenation of alcohol, a development which subsequently led, in 1831, to the industrial scale synthesis of sulphuric acid using a platinum catalyst.

In 1803, cerium was the first of the lanthanide metals to be discovered, in Bastnäs, Sweden by Jöns Jakob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger, and independently by Martin Heinrich Klaproth in Germany. The lanthanide metals were largely regarded as oddities until the 1960s when methods were developed to more efficiently separate them from one another. They have subsequently found uses in cell phones, magnets, lasers, lighting, batteries, catalytic converters, and in other applications enabling modern technologies.

Other metals discovered and prepared during this time were cobalt, nickel, manganese, molybdenum, tungsten, and chromium; and some of the platinum group metals, palladium, osmium, iridium, and rhodium.

Light metals

All metals discovered until 1809 had relatively high densities; their heaviness was regarded as a singularly distinguishing criterion. From 1809 onward, light metals such as sodium, potassium, and strontium were isolated. Their low densities challenged conventional wisdom as to the nature of metals. They behaved chemically as metals however, and were subsequently recognised as such.

Aluminium was discovered in 1824 but it was not until 1886 that an industrial large-scale production method was developed. Prices of aluminium dropped and aluminium became widely used in jewelry, everyday items, eyeglass frames, optical instruments, tableware, and foil in the 1890s and early 20th century. Aluminium’s ability to form hard yet light alloys with other metals provided the metal many uses at the time. During World War I, major governments demanded large shipments of aluminium for light strong airframes. The most common metal in use for electric power transmission today is aluminium-conductor steel-reinforced. Also seeing much use is all-aluminium-alloy conductor. Aluminium is used because it has about half the weight of a comparable resistance copper cable (though larger diameter due to lower specific conductivity), as well as being cheaper. Copper was more popular in the past and is still in use, especially at lower voltages and for grounding.

While pure metallic titanium (99.9%) was first prepared in 1910 it was not used outside the laboratory until 1932. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet Union pioneered the use of titanium in military and submarine applications as part of programs related to the Cold War. Starting in the early 1950s, titanium came into use extensively in military aviation, particularly in high-performance jets, starting with aircraft such as the F-100 Super Sabre and Lockheed A-12 and SR-71.

Metallic scandium was produced for the first time in 1937. The first pound of 99% pure scandium metal was produced in 1960. Production of aluminium-scandium alloys began in 1971 following a U.S. patent. Aluminium-scandium alloys were also developed in the USSR.

-

Chunks of sodium

-

Potassium pearls under paraffin oil. Size of the largest pearl is 0.5 cm.

-

Strontium crystals

-

Aluminium chunk,

2.6 grams, 1 x 2 cm -

A bar of titanium crystals

-

Scandium, including a 1 cm3 cube

The age of steel

White-hot steel pours like water from a 35-ton electric furnace, at the Allegheny Ludlum Steel Corporation, in Brackenridge, Pennsylvania.

The modern era in steelmaking began with the introduction of Henry Bessemer’s Bessemer process in 1855, the raw material for which was pig iron. His method let him produce steel in large quantities cheaply, thus mild steel came to be used for most purposes for which wrought iron was formerly used. The Gilchrist-Thomas process (or basic Bessemer process) was an improvement to the Bessemer process, made by lining the converter with a basic material to remove phosphorus.

Due to its high tensile strength and low cost, steel came to be a major component used in buildings, infrastructure, tools, ships, automobiles, machines, appliances, and weapons.

In 1872, the Englishmen Clark and Woods patented an alloy that would today be considered a stainless steel. The corrosion resistance of iron-chromium alloys had been recognized in 1821 by French metallurgist Pierre Berthier. He noted their resistance against attack by some acids and suggested their use in cutlery. Metallurgists of the 19th century were unable to produce the combination of low carbon and high chromium found in most modern stainless steels, and the high-chromium alloys they could produce were too brittle to be practical. It was not until 1912 that the industrialisation of stainless steel alloys occurred in England, Germany, and the United States.

The last stable metallic elements

By 1900 three metals with atomic numbers less than lead (#82), the heaviest stable metal, remained to be discovered: elements 71, 72, 75.

Von Welsbach, in 1906, proved that the old ytterbium also contained a new element (#71), which he named cassiopeium. Urbain proved this simultaneously, but his samples were very impure and only contained trace quantities of the new element. Despite this, his chosen name lutetium was adopted.

In 1908, Ogawa found element 75 in thorianite but assigned it as element 43 instead of 75 and named it nipponium. In 1925 Walter Noddack, Ida Eva Tacke, and Otto Berg announced its separation from gadolinite and gave it the present name, rhenium.

Georges Urbain claimed to have found element 72 in rare-earth residues, while Vladimir Vernadsky independently found it in orthite. Neither claim was confirmed due to World War I, and neither could be confirmed later, as the chemistry they reported does not match that now known for hafnium. After the war, in 1922, Coster and Hevesy found it by X-ray spectroscopic analysis in Norwegian zircon. Hafnium was thus the last stable element to be discovered, though rhenium was the last to be correctly recognized.

-

Lutetium, including a 1 cm3 cube

-

Rhenium, including a 1 cm3 cube

-

Hafnium, in the form of a 1.7 kg bar

By the end of World War II scientists had synthesized four post-uranium elements, all of which are radioactive (unstable) metals: neptunium (in 1940), plutonium (1940–41), and curium and americium (1944), representing elements 93 to 96. The first two of these were eventually found in nature as well. Curium and americium were by-products of the Manhattan project, which produced the world’s first atomic bomb in 1945. The bomb was based on the nuclear fission of uranium, a metal first thought to have been discovered nearly 150 years earlier.

Post-World War II developments

Superalloys

Superalloys composed of combinations of Fe, Ni, Co, and Cr, and lesser amounts of W, Mo, Ta, Nb, Ti, and Al were developed shortly after World War II for use in high performance engines, operating at elevated temperatures (above 650 °C (1,200 °F)). They retain most of their strength under these conditions, for prolonged periods, and combine good low-temperature ductility with resistance to corrosion or oxidation. Superalloys can now be found in a wide range of applications including land, maritime, and aerospace turbines, and chemical and petroleum plants.

Transcurium metals

The successful development of the atomic bomb at the end of World War II sparked further efforts to synthesize new elements, nearly all of which are, or are expected to be, metals, and all of which are radioactive. It was not until 1949 that element 97 (berkelium), next after element 96 (curium), was synthesized by firing alpha particles at an americium target. In 1952, element 100 (fermium) was found in the debris of the first hydrogen bomb explosion; hydrogen, a nonmetal, had been identified as an element nearly 200 years earlier. Since 1952, elements 101 (mendelevium) to 118 (oganesson) have been synthesized.

Bulk metallic glasses

A metallic glass (also known as an amorphous or glassy metal) is a solid metallic material, usually an alloy, with a disordered atomic-scale structure. Most pure and alloyed metals, in their solid state, have atoms arranged in a highly ordered crystalline structure. Amorphous metals have a non-crystalline glass-like structure. But unlike common glasses, such as window glass, which are typically electrical insulators, amorphous metals have good electrical conductivity. Amorphous metals are produced in several ways, including extremely rapid cooling, physical vapor deposition, solid-state reaction, ion irradiation, and mechanical alloying. The first reported metallic glass was an alloy (Au75Si25) produced at Caltech in 1960. More recently, batches of amorphous steel with three times the strength of conventional steel alloys have been produced. Currently, the most important applications rely on the special magnetic properties of some ferromagnetic metallic glasses. The low magnetization loss is used in high-efficiency transformers. Theft control ID tags and other article surveillance schemes often use metallic glasses because of these magnetic properties.

Shape-memory alloys

A shape-memory alloy (SMA) is an alloy that «remembers» its original shape and when deformed returns to its pre-deformed shape when heated. While the shape memory effect had been first observed in 1932, in an Au-Cd alloy, it was not until 1962, with the accidental discovery of the effect in a Ni-Ti alloy that research began in earnest, and another ten years before commercial applications emerged. SMA’s have applications in robotics and automotive, aerospace, and biomedical industries. There is another type of SMA, called a ferromagnetic shape-memory alloy (FSMA), that changes shape under strong magnetic fields. These materials are of particular interest as the magnetic response tends to be faster and more efficient than temperature-induced responses.

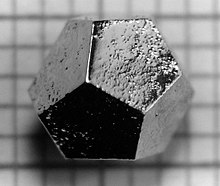

Quasicyrstalline alloys

In 1984, Israeli chemist Dan Shechtman found an aluminum-manganese alloy having five-fold symmetry, in breach of crystallographic convention at the time which said that crystalline structures could only have two-, three-, four-, or six-fold symmetry. Due to fear of the scientific community’s reaction, it took him two years to publish the results for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011. Since this time, hundreds of quasicrystals have been reported and confirmed. They exist in many metallic alloys (and some polymers). Quasicrystals are found most often in aluminum alloys (Al-Li-Cu, Al-Mn-Si, Al-Ni-Co, Al-Pd-Mn, Al-Cu-Fe, Al-Cu-V, etc.), but numerous other compositions are also known (Cd-Yb, Ti-Zr-Ni, Zn-Mg-Ho, Zn-Mg-Sc, In-Ag-Yb, Pd-U-Si, etc.). Quasicrystals effectively have infinitely large unit cells. Icosahedrite Al63Cu24Fe13, the first quasicrystal found in nature, was discovered in 2009. Most quasicrystals have ceramic-like properties including low electrical conductivity (approaching values seen in insulators) and low thermal conductivity, high hardness, brittleness, and resistance to corrosion, and non-stick properties. Quasicrystals have been used to develop heat insulation, LEDs, diesel engines, and new materials that convert heat to electricity. New applications may take advantage of the low coefficient of friction and the hardness of some quasicrystalline materials, for example embedding particles in plastic to make strong, hard-wearing, low-friction plastic gears. Other potential applications include selective solar absorbers for power conversion, broad-wavelength reflectors, and bone repair and prostheses applications where biocompatibility, low friction, and corrosion resistance are required.

Complex metallic alloys

Complex metallic alloys (CMAs) are intermetallic compounds characterized by large unit cells comprising some tens up to thousands of atoms; the presence of well-defined clusters of atoms (frequently with icosahedral symmetry); and partial disorder within their crystalline lattices. They are composed of two or more metallic elements, sometimes with metalloids or chalcogenides added. They include, for example, NaCd2, with 348 sodium atoms and 768 cadmium atoms in the unit cell. Linus Pauling attempted to describe the structure of NaCd2 in 1923, but did not succeed until 1955. At first called «giant unit cell crystals», interest in CMAs, as they came to be called, did not pick up until 2002, with the publication of a paper called «Structurally Complex Alloy Phases», given at the 8th International Conference on Quasicrystals. Potential applications of CMAs include as heat insulation; solar heating; magnetic refrigerators; using waste heat to generate electricity; and coatings for turbine blades in military engines.

High-entropy alloys

High-entropy alloys (HEAs) such as AlLiMgScTi are composed of equal or nearly equal quantities of five or more metals. Compared to conventional alloys with only one or two base metals, HEAs have considerably better strength-to-weight ratios, higher tensile strength, and greater resistance to fracturing, corrosion, and oxidation. Although HEAs were described as early as 1981, significant interest did not develop until the 2010s; they continue to be the focus of research in materials science and engineering because of their potential for desirable properties.

MAX phase alloys

In a MAX phase alloy, M is an early transition metal, A is an A group element (mostly group IIIA and IVA, or groups 13 and 14), and X is either carbon or nitrogen. Examples are Hf2SnC and Ti4AlN3. Such alloys have some of the best properties of metals and ceramics. These properties include high electrical and thermal conductivity, thermal shock resistance, damage tolerance, machinability, high elastic stiffness, and low thermal expansion coefficients.[43] They can be polished to a metallic luster because of their excellent electrical conductivities. During mechanical testing, it has been found that polycrystalline Ti3SiC2 cylinders can be repeatedly compressed at room temperature, up to stresses of 1 GPa, and fully recover upon the removal of the load. Some MAX phases are also highly resistant to chemical attack (e.g. Ti3SiC2) and high-temperature oxidation in air (Ti2AlC, Cr2AlC2, and Ti3AlC2). Potential applications for MAX phase alloys include: as tough, machinable, thermal shock-resistant refractories; high-temperature heating elements; coatings for electrical contacts; and neutron irradiation resistant parts for nuclear applications. While MAX phase alloys were discovered in the 1960s, the first paper on the subject was not published until 1996.

See also

- Colored gold

- Ductility

- Ferrous metallurgy

- Metal theft

- Metallurgy

- Metalworking

- Polymetal

- Properties of metals, metalloids, and nonmetals

- Structural steel

- Transition metal

Notes

- ^ This is a simplified explanation; other factors may include atomic radius, nuclear charge, number of bond orbitals, overlap of orbital energies, and crystal form.[6]

- ^ Trace elements having an abundance equalling or much less than one part per trillion (namely Tc, Pm, Po, At, Ra, Ac, Pa, Np, and Pu) are not shown.

- ^ In some cases, for example in the presence of high energy gamma rays or in a very high temperature hydrogen rich environment, the subject nuclei may experience neutron loss or proton gain resulting in the production of (comparatively rare) neutron deficient isotopes.[22]

- ^ The ejection of matter when two neutron stars collide is attributed to the interaction of their tidal forces, possible crustal disruption, and shock heating (which is what happens if you floor the accelerator in car when the engine is cold).[25]

- ^ Iron, cobalt, nickel, and tin are also siderophiles from a whole of Earth perspective.

- ^ Another life-enabling role for iron is as a key constituent of hemoglobin, which enables the transportation of oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body.

- ^ Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12% tin and often with the addition of other metals (such as aluminum, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals or metalloids such as arsenic, phosphorus, or silicon.

- ^ The Chalybean peoples of Pontus in Asia Minor were being concurrently celebrated for working in iron and steel. Unbeknownst to them, their iron contained a high amount of manganese, enabling the production of a superior form of steel.