МОЧЕВИНА

- МОЧЕВИНА

- МОЧЕВИНА ( Ureа рurа ). Синонимы: Карбамид, Сarbamid, Саrbamidum, Ureaphil. Белый кристаллический порошок или бесцветные кристаллы солоновато-горьковатого вкуса, без запаха. Легко растворима в воде (1 : 1), растворима в спирте (1 : 5). Водные растворы имеют нейтральную реакцию. Растворение в воде происходит с поглощением тепла. Мочевину применяли в прошлом в качестве диуретического средства. Ее назначали внутрь (обычно в сахарном или фруктовом сиропе) по 15 — 20 г на прием 2 — 5 раз в день. В этих дозах она оказывает диуретический эффект, однако при нарушении функции почек может резко повыситься содержание азота в организме. Диуретический эффект связан с действием целых молекул мочевины; в организме человека они не подвергаются обменным процессам и фильтруются в большом количестве (50 — 60 %) через клубочки без обратного всасывания. Высокое осмотическое давление, создаваемое в канальцах, вызывает сильный водный диурез. В настоящее время в связи с появлением новых эффективных диуретических средств мочевину для этой цели не применяют. Мочевину назначают в основном в качестве дегидратирующего средства для предупреждения и уменьшения отека мозга и токсического отека легких, а также как эффективное средство, понижающее внутриглазное давление. Механизм противоотечного эффекта и гипотензивного действия (по отношению к внутриглазнаму давлению) мочевины недостаточно ясен. Предполагают, что важную роль играет осмотический эффект. Резкое повышение осмотического давления крови, вызванное введением гипертонических растворов мочевины, приводит к активному поступлению в кровяное русло жидкости из тканей и органов, и том числе из полостей и тканей мозга и глаза. Через гематоэнцефалический барьер и в глазное яблоко мочевина проникает плохо; таким образом, создается значительная разница между осмотическим давлением крови, с одной стороны, и спинномозговой жидкости и жидкостей глаза — с другой. Гипотензивное действие в отношении внутричерепного и внутриглазного давления непосредственно не связано с диуретическим действием. Установлено, что в условиях эксперимента гипотензивный эффект сохраняется после двусторонней нефрэктомии. Однако диуретический эффект способствует понижению давления. Имеются также данные, позволяющие считать, что определенную роль в гипотензивном эффекте играют центральные механизмы (влияние гипертонического раствора на осморецептивные поля в гипоталамусе). Мочевина нашла применение в нейрохирургии для предупреждения и уменьшения отека мозга, особенно в ранних стадиях его развития. В офтальмологической практике мочевину назначают при глаукоме, особенно во время острого приступа, а также при подготовке больных с высоким уровнем офтальмотонуса к операциям. Применяют мочевину внутривенно, а также внутрь. Для внутривенного введения используют специально очищенный, стерильный, лиофилизированный препарат мочевины, называемый » Мочевина для инъекций » (Urea pro injectionibus). Примеси биурета и аммиака в неочищенных препаратах могут вызывать гемолиз эритроцитов. За рубежом для внутривенных вливаний выпускается очищенная мочевина в растворе инвертного сахара под назвзнием » Urevert «. Раствор мочевины для внутривенного введения готовят непосредственно перед введением в асептических условиях. При стоянии растворы разлагаются и могут вызвать гемолиз. Применяют 30 % раствор, приготовленный на 10 % растворе глюкозы. Растворение происходит с поглощением тепла (раствор охлаждается). Раствор выдерживают, пока его температура не достигнет комнатной. Вводят раствор капельно со скоростью 40 — 60 — 80 капель в минуту. Только при необходимости получить быстрый и максимальный эффект увеличивают скорость введения до 80 — 120 капель в минуту. Общая доза 0,5 — 1,5 г (в среднем 1 г) мочевины на 1 кг массы тела больного. Эффект наступает обычно через 15 — 30 мин, достигает максимума через 1 — 1,5 ч от начала введения раствора и длится 5 — 6 ч и более (до 14 ч). При необходимости можно вводить повторно (не более 2 — 3 раз) с промежутком 12 — 24 ч. При отеке мозга отмечаются снижение внутричерепного давления, уменьшение напряжения твердой мозговой оболочки, появление пульсации; при глаукоме — снижение внутриглазного давления, Внутрь назначают мочевину в виде 50 % или 30 %, раствора в сахарном сиропе в дозе 0,75 — 1,5 г/кг. Имеются данные о том, что при глаукоме гипотензивный эффект после перорального применения мочевины наступает в те же сроки (30 — 45 мин), что и при внутривенном капельном введении. Однако, дегидратирующее влияние на мозговую ткань проявляется при пероральном введении только через несколько часов. При соблюдении необходимых правил введения мочевины не наблюдается осложнений, не изменяются показатели крови и мочи. В первые часы отмечается повышение уровня остаточного азота в крови, затем происходит быстрое возвращение к исходным цифрам. В некоторых случаях при внутривенном введении повышается АД. В связи с обезвоживанием организма больные испытывают жажду и сухость во рту. Для предупреждения нарушения водного баланса в первые сутки после применения препарата следует вводить внутривенно капельно изотонический раствор глюкозы или натрия хлорида (500 — 800 мл) с добавлением аскорбиновой кислоты (0,2 — О,3 г) и витамина В 1 (О,1 — 0,15 г). Недопустимо назначать больным диуретики. При вливании раствора мочевины больным, находящимся в бессознательном состоянии или под наркозом, для отведения мочи следует ввести в мочевой пузырь катетер. При внутривенном введении нельзя допускать попадания раствора под кожу во избежание раздражения и некроза тканей. В отдельных случаях при внутривенном введении могут наблюдаться тромбоз вен и ограниченные флебиты. При приеме препарата внутрь возможны диспепсические явления (тошнота, изжога, рвота). Противопоказания: выраженная почечная и печеночная недостаточность, резко выраженная сердечно-сосудистая недостаточность (возможный циркуляторный коллапс). Нежелательно применение мочевины при отеке мозга, связанном с острым нарушением мозгового кровообращения, так как вслед за мощным противоотечным эффектом возможно викарное расширение сосудов мозга, что может привести к повторному кровотечению или присоединению к размягчению мозга геморрагического компонента. Форма выпуска: для внутривенного введении в сухом стерильном виде по 30; 45; 60 и 90 г в герметически закрытых флаконах емкостью 250 и 450 мл. К каждому флакону прилагается флакон с соответствующим количеством 10 % раствора глюкозы (75; 115; 150 и 225 мл), необходимым для получения ЗО % раствора мочевины. Растворяют препарат eх temporе. Мочевина обладает также кератолитическим действием. Центральным научно-исследовательским кожно-венерологическим институтом были предложены пластырь » Уреапласт » (мочевины 20 г, воды 10 г, пчелиного воска 5 г, ланолина 20 г, свинцового пластыря 45 г) и мазь (30 % мочевины) для применения в качестве кератолитических средств при лечении онихомикозов. За рубежам выпускаются кератолитические кремы, содержащие 10 % мочевины (Кеratolan, Саrbaderm и др.), применяемые для лечения ихтиоза, ихтиозооформных дерматитов, гиперкератоза. Раствор мочевины (10 %) назначают в виде орошений, промываний, влажных повязок для лечения гнойных ран. Применяют также 25 % эмульсию. Происходит ускоренное очищение ран от некротических масс, а также ускоренное заживление.

Словарь медицинских препаратов.

2005.

Синонимы:

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «МОЧЕВИНА» в других словарях:

-

Мочевина — Мочевина … Википедия

-

МОЧЕВИНА — (карбамид), (NH2)2CO, бесцветные кристаллы, tпл 135 шC. Растворима в воде. Мочевина конечный продукт белкового обмена у большинства позвоночных животных и человека. Образуется в печени, выводится с мочой. В промышленности мочевину синтезируют из… … Современная энциклопедия

-

МОЧЕВИНА — (карбамид) (NH2)2СО, бесцветные кристаллы, tпл 135 .С. Растворима в воде. Мочевина конечный продукт белкового обмена у большинства позвоночных животных и человека. Образуется в печени (см. Орнитиновый цикл). Выводится с мочой. В промышленности… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

МОЧЕВИНА — (карбамид) NH2.CO.NHa, диа мид угольной к ты, главная составная часть мочи человека и других млекопитающих, амфибий и рыб. В малых количествах содержится в крови (главная составная часть остаточного азота сыворотки крови), лимфе, трансудатах,… … Большая медицинская энциклопедия

-

МОЧЕВИНА — (СО(NН2)2), органическое соединение, белое кристаллическое твердое вещество, впервые выделенное из мочи. Большинство позвоночных теряют больше всего азота с мочой. Моча человека содержит около 25 г мочевины на литр. Из за высокого содержания… … Научно-технический энциклопедический словарь

-

Мочевина — – CO(NH2)2 (карбамид) – в качестве самостоятельной противоморозной добавки обычно не применяется. В составе комплексных противоморозных добавок (ННХКМ, ННКМ, ННК+М, НКМ, НК+М) выполняет роль пластификатора бетонной смеси, а также,… … Энциклопедия терминов, определений и пояснений строительных материалов

-

МОЧЕВИНА — МОЧЕВИНА, мочевины, мн. нет, жен. (хим.). Составная часть мочи млекопитающих, птиц и некоторых пресмыкающихся кристаллическое, вещество, растворимое в воде. Толковый словарь Ушакова. Д.Н. Ушаков. 1935 1940 … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

МОЧЕВИНА — карбамид, H2NCONH2 полный амид угольной к ты. Присутствует в жидкостях и тканях животных, в грибах. Образование М. один из механизмов связывания токсич. аммиака в организме. Конечный продукт белкового обмена у т. н. уреотелических животных… … Биологический энциклопедический словарь

-

мочевина — сущ., кол во синонимов: 5 • карбамид (2) • минерал (5627) • полимочевина (1) • … Словарь синонимов

-

мочевина — ы; ж. Кристаллическое, растворимое в воде азотистое вещество, являющееся конечным продуктом белкового обмена у человека и многих животных. Определить процент мочевины в моче. * * * мочевина (карбамид), (NH2)2CO, бесцветные кристаллы, tпл 135°C.… … Энциклопедический словарь

Мочевина

(Urea pura)

Содержание

- Структурная формула

- Русское название

- Английское название

- Латинское название вещества Мочевина

- Брутто формула

- Фармакологическая группа вещества Мочевина

- Нозологическая классификация

- Код CAS

- Торговые названия с действующим веществом Мочевина

Структурная формула

Русское название

Мочевина

Латинское название вещества Мочевина

Urea pura (род. Ureae purae)

Фармакологическая группа вещества Мочевина

Торговые названия с действующим веществом Мочевина

| Торговое название | Цена за упаковку, руб. |

|---|---|

| Уродерм® |

от 136.90 до 526.00 |

Наш сайт использует файлы cookie, чтобы улучшить работу сайта, повысить его эффективность и удобство. Продолжая использовать сайт rlsnet.ru, вы соглашаетесь с условиями использования файлов cookie.

|

||

|

||

| Names | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | urea , carbamide | |

| Preferred IUPAC name

Urea[1] |

||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Carbonyl diamide[1] |

||

Other names

|

||

| Identifiers | ||

|

CAS Number |

|

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

|

|

Beilstein Reference |

635724 | |

| ChEBI |

|

|

| ChEMBL |

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

|

| DrugBank |

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.286 |

|

| E number | E927b (glazing agents, …) | |

|

Gmelin Reference |

1378 | |

|

IUPHAR/BPS |

|

|

| KEGG |

|

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

|

| UNII |

|

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

|

InChI

|

||

|

SMILES

|

||

| Properties | ||

|

Chemical formula |

CO(NH2)2 | |

| Molar mass | 60.06 g/mol | |

| Appearance | White solid | |

| Density | 1.32 g/cm3 | |

| Melting point | 133 to 135 °C (271 to 275 °F; 406 to 408 K) | |

|

Solubility in water |

545 g/L (at 25 °C)[2] | |

| Solubility | 500 g/L glycerol[3]

50 g/L ethanol |

|

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.9[5] | |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

−33.4·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | ||

|

Dipole moment |

4.56 D | |

| ThermochemistryCRC Handbook | ||

|

Std enthalpy of |

−333.19 kJ/mol | |

|

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) |

−197.15 kJ/mol | |

| Pharmacology | ||

|

ATC code |

B05BC02 (WHO) D02AE01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | ||

| GHS labelling: | ||

|

Pictograms |

|

|

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

1 1 0 |

|

| Flash point | Non-flammable | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | ||

|

LD50 (median dose) |

8500 mg/kg (oral, rat) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | JT Baker | |

| Related compounds | ||

|

Related ureas |

Thiourea Hydroxycarbamide |

|

|

Related compounds |

|

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula CO(NH2)2. This amide has two amino groups (–NH2) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important role in the metabolism of nitrogen-containing compounds by animals and is the main nitrogen-containing substance in the urine of mammals. It is a colorless, odorless solid, highly soluble in water, and practically non-toxic (LD50 is 15 g/kg for rats).[6] Dissolved in water, it is neither acidic nor alkaline. The body uses it in many processes, most notably nitrogen excretion. The liver forms it by combining two ammonia molecules (NH3) with a carbon dioxide (CO2) molecule in the urea cycle. Urea is widely used in fertilizers as a source of nitrogen (N) and is an important raw material for the chemical industry.

In 1828 Friedrich Wöhler discovered that urea can be produced from inorganic starting materials, which was an important conceptual milestone in chemistry. This showed for the first time that a substance previously known only as a byproduct of life could be synthesized in the laboratory without biological starting materials, thereby contradicting the widely held doctrine of vitalism, which stated that only living organisms could produce the chemicals of life.

Uses[edit]

Agriculture[edit]

A plant in Bangladesh that produces urea fertilizer.

More than 90% of world industrial production of urea is destined for use as a nitrogen-release fertilizer.[7] Urea has the highest nitrogen content of all solid nitrogenous fertilizers in common use. Therefore, it has a low transportation cost per unit of nitrogen nutrient. The most common impurity of synthetic urea is biuret, which impairs plant growth. Urea breaks down in the soil to give ammonium. The ammonium is taken up by the plant. In some soils, the ammonium is oxidized by bacteria to give nitrate, which is also a plant nutrient. The loss of nitrogenous compounds to the atmosphere and runoff is both wasteful and environmentally damaging. For this reason, urea is sometimes pretreated or modified to enhance the efficiency of its agricultural use. One such technology is controlled-release fertilizers, which contain urea encapsulated in an inert sealant. Another technology is the conversion of urea into derivatives, such as formaldehyde, which degrades into ammonia at a pace matching plants’ nutritional requirements.

Resins[edit]

Urea is a raw material for the manufacture of two main classes of materials: urea-formaldehyde resins and urea-melamine-formaldehyde used mostly in wood based panels such as particleboard,

fiberboard and plywood, among others.

Explosives[edit]

Urea can be used to make urea nitrate, a high explosive that is used industrially and as part of some improvised explosive devices.

Automobile systems[edit]

Urea is used in Selective Non-Catalytic Reduction (SNCR) and Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) reactions to reduce the NOx pollutants in exhaust gases from combustion from diesel, dual fuel, and lean-burn natural gas engines. The BlueTec system, for example, injects a water-based urea solution into the exhaust system. Ammonia (NH3) first produced by the hydrolysis of urea reacts with nitrogen oxides (NOx) and is converted into nitrogen gas (N2) and water within the catalytic converter. The conversion of noxious NOx to innocuous N2 is described by the following simplified global equation:[8]

- 4 NO + 4 NH3 + O2 → 4 N2 + 6 H2O

When urea is used, a pre-reaction (hydrolysis) occurs to first convert it to ammonia:

- CO(NH2)2 + H2O → 2 NH3 + CO2

Being a solid highly soluble in water (545 g/L at 25 °C),[2] urea is much easier and safer to handle and store than the more irritant, caustic and hazardous ammonia (NH3), so it is the reactant of choice. Trucks and cars using these catalytic converters need to carry a supply of diesel exhaust fluid, also sold as AdBlue, a solution of urea in water.

Laboratory uses[edit]

Urea in concentrations up to 10 M is a powerful protein denaturant as it disrupts the noncovalent bonds in the proteins. This property can be exploited to increase the solubility of some proteins.

A mixture of urea and choline chloride is used as a deep eutectic solvent (DES), a substance similar to ionic liquid. When used in a deep eutectic solvent, urea gradually denatures the proteins that are solubilized.[9]

Urea can in principle serve as a hydrogen source for subsequent power generation in fuel cells. Urea present in urine/wastewater can be used directly (though bacteria normally quickly degrade urea). Producing hydrogen by electrolysis of urea solution occurs at a lower voltage (0.37 V) and thus consumes less energy than the electrolysis of water (1.2 V).[10]

Urea in concentrations up to 8 M can be used to make fixed brain tissue transparent to visible light while still preserving fluorescent signals from labeled cells. This allows for much deeper imaging of neuronal processes than previously obtainable using conventional one photon or two photon confocal microscopes.[11]

Medical use[edit]

Urea-containing creams are used as topical dermatological products to promote rehydration of the skin. Urea 40% is indicated for psoriasis, xerosis, onychomycosis, ichthyosis, eczema, keratosis, keratoderma, corns, and calluses. If covered by an occlusive dressing, 40% urea preparations may also be used for nonsurgical debridement of nails. Urea 40% «dissolves the intercellular matrix»[12][13] of the nail plate. Only diseased or dystrophic nails are removed, as there is no effect on healthy portions of the nail.[citation needed] This drug (as carbamide peroxide) is also used as an earwax removal aid.[14]

Urea has also been studied as a diuretic. It was first used by Dr. W. Friedrich in 1892.[15] In a 2010 study of ICU patients, urea was used to treat euvolemic hyponatremia and was found safe, inexpensive, and simple.[16]

Like saline, urea has been injected into the uterus to induce abortion, although this method is no longer in widespread use.[17]

The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) test is a measure of the amount of nitrogen in the blood that comes from urea. It is used as a marker of renal function, though it is inferior to other markers such as creatinine because blood urea levels are influenced by other factors such as diet, dehydration,[18] and liver function.

Urea has also been studied as an excipient in Drug-coated Balloon (DCB) coating formulation to enhance local drug delivery to stenotic blood vessels.[19][20] Urea, when used as an excipient in small doses (~3 μg/mm2) to coat DCB surface was found to form crystals that increase drug transfer without adverse toxic effects on vascular endothelial cells.[21]

Urea labeled with carbon-14 or carbon-13 is used in the urea breath test, which is used to detect the presence of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in the stomach and duodenum of humans, associated with peptic ulcers. The test detects the characteristic enzyme urease, produced by H. pylori, by a reaction that produces ammonia from urea. This increases the pH (reduces the acidity) of the stomach environment around the bacteria. Similar bacteria species to H. pylori can be identified by the same test in animals such as apes, dogs, and cats (including big cats).

Miscellaneous uses[edit]

- An ingredient in diesel exhaust fluid (DEF), which is 32.5% urea and 67.5% de-ionized water. DEF is sprayed into the exhaust stream of diesel vehicles to break down dangerous NOx emissions into harmless nitrogen and water.

- A component of animal feed, providing a relatively cheap source of nitrogen to promote growth

- A non-corroding alternative to rock salt for road de-icing.[22] It is often the main ingredient of pet friendly salt substitutes although it is less effective than traditional rock salt or calcium chloride.[23]

- A main ingredient in hair removers such as Nair and Veet

- A browning agent in factory-produced pretzels

- An ingredient in some skin cream,[24] moisturizers, hair conditioners, and shampoos

- A cloud seeding agent, along with other salts[25]

- A flame-proofing agent, commonly used in dry chemical fire extinguisher charges such as the urea-potassium bicarbonate mixture

- An ingredient in many tooth whitening products

- An ingredient in dish soap

- Along with diammonium phosphate, as a yeast nutrient, for fermentation of sugars into ethanol

- A nutrient used by plankton in ocean nourishment experiments for geoengineering purposes

- As an additive to extend the working temperature and open time of hide glue

- As a solubility-enhancing and moisture-retaining additive to dye baths for textile dyeing or printing[26]

- As an optical parametric oscillator in nonlinear optics[27][28]

Adverse effects[edit]

Urea can be irritating to skin, eyes, and the respiratory tract. Repeated or prolonged contact with urea in fertilizer form on the skin may cause dermatitis.[citation needed]

High concentrations in the blood can be damaging. Ingestion of low concentrations of urea, such as are found in typical human urine, are not dangerous with additional water ingestion within a reasonable time-frame. Many animals (e.g. camels, rodents or dogs) have a much more concentrated urine which may contain a higher urea amount than normal human urine.

Urea can cause algal blooms to produce toxins, and its presence in the runoff from fertilized land may play a role in the increase of toxic blooms.[29]

The substance decomposes on heating above melting point, producing toxic gases, and reacts violently with strong oxidants, nitrites, inorganic chlorides, chlorites and perchlorates, causing fire and explosion.[30]

Physiology[edit]

Amino acids from ingested food that are used for the synthesis of proteins and other biological substances — or produced from catabolism of muscle protein — are oxidized by the body as an alternative source of energy, yielding urea and carbon dioxide.[31] The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase; the amino group is then fed into the urea cycle. The first step in the conversion of amino acids from protein into metabolic waste in the liver is removal of the alpha-amino nitrogen, which results in ammonia. Because ammonia is toxic, it is excreted immediately by fish, converted into uric acid by birds, and converted into urea by mammals.[32]

Ammonia (NH3) is a common byproduct of the metabolism of nitrogenous compounds. Ammonia is smaller, more volatile and more mobile than urea. If allowed to accumulate, ammonia would raise the pH in cells to toxic levels. Therefore, many organisms convert ammonia to urea, even though this synthesis has a net energy cost. Being practically neutral and highly soluble in water, urea is a safe vehicle for the body to transport and excrete excess nitrogen.

Urea is synthesized in the body of many organisms as part of the urea cycle, either from the oxidation of amino acids or from ammonia. In this cycle, amino groups donated by ammonia and L-aspartate are converted to urea, while L-ornithine, citrulline, L-argininosuccinate, and L-arginine act as intermediates. Urea production occurs in the liver and is regulated by N-acetylglutamate. Urea is then dissolved into the blood (in the reference range of 2.5 to 6.7 mmol/L) and further transported and excreted by the kidney as a component of urine. In addition, a small amount of urea is excreted (along with sodium chloride and water) in sweat.

In water, the amine groups undergo slow displacement by water molecules, producing ammonia, ammonium ion, and bicarbonate ion. For this reason, old, stale urine has a stronger odor than fresh urine.

Humans[edit]

The cycling of and excretion of urea by the kidneys is a vital part of mammalian metabolism. Besides its role as carrier of waste nitrogen, urea also plays a role in the countercurrent exchange system of the nephrons, that allows for reabsorption of water and critical ions from the excreted urine. Urea is reabsorbed in the inner medullary collecting ducts of the nephrons,[33] thus raising the osmolarity in the medullary interstitium surrounding the thin descending limb of the loop of Henle, which makes the water reabsorb.

By action of the urea transporter 2, some of this reabsorbed urea eventually flows back into the thin descending limb of the tubule,[34] through the collecting ducts, and into the excreted urine. The body uses this mechanism, which is controlled by the antidiuretic hormone, to create hyperosmotic urine — i.e., urine with a higher concentration of dissolved substances than the blood plasma. This mechanism is important to prevent the loss of water, maintain blood pressure, and maintain a suitable concentration of sodium ions in the blood plasma.

The equivalent nitrogen content (in grams) of urea (in mmol) can be estimated by the conversion factor 0.028 g/mmol.[35] Furthermore, 1 gram of nitrogen is roughly equivalent to 6.25 grams of protein, and 1 gram of protein is roughly equivalent to 5 grams of muscle tissue. In situations such as muscle wasting, 1 mmol of excessive urea in the urine (as measured by urine volume in litres multiplied by urea concentration in mmol/L) roughly corresponds to a muscle loss of 0.67 gram.

Other species[edit]

In aquatic organisms the most common form of nitrogen waste is ammonia, whereas land-dwelling organisms convert the toxic ammonia to either urea or uric acid. Urea is found in the urine of mammals and amphibians, as well as some fish. Birds and saurian reptiles have a different form of nitrogen metabolism that requires less water, and leads to nitrogen excretion in the form of uric acid. Tadpoles excrete ammonia, but shift to urea production during metamorphosis. Despite the generalization above, the urea pathway has been documented not only in mammals and amphibians, but in many other organisms as well, including birds, invertebrates, insects, plants, yeast, fungi, and even microorganisms.[36]

Analysis[edit]

Urea is readily quantified by a number of different methods, such as the diacetyl monoxime colorimetric method, and the Berthelot reaction (after initial conversion of urea to ammonia via urease). These methods are amenable to high throughput instrumentation, such as automated flow injection analyzers[37] and 96-well micro-plate spectrophotometers.[38]

[edit]

Ureas describes a class of chemical compounds that share the same functional group, a carbonyl group attached to two organic amine residues: R1R2N−C(=O)−NR3R4, where R1, R2, R3 and R4 groups are hydrogen (–H), organyl or other groups. Examples include carbamide peroxide, allantoin, and hydantoin. Ureas are closely related to biurets and related in structure to amides, carbamates, carbodiimides, and thiocarbamides.

History[edit]

Urea was first discovered in urine in 1727 by the Dutch scientist Herman Boerhaave,[39] although this discovery is often attributed to the French chemist Hilaire Rouelle as well as William Cruickshank.[40]

Boerhaave used the following steps to isolate urea:[41][42]

- Boiled off water, resulting in a substance similar to fresh cream

- Used filter paper to squeeze out remaining liquid

- Waited a year for solid to form under an oily liquid

- Removed the oily liquid

- Dissolved the solid in water

- Used recrystallization to tease out the urea

In 1828, the German chemist Friedrich Wöhler obtained urea artificially by treating silver cyanate with ammonium chloride.[43][44][45]

- AgNCO + [NH4]Cl → CO(NH2)2 + AgCl

This was the first time an organic compound was artificially synthesized from inorganic starting materials, without the involvement of living organisms. The results of this experiment implicitly discredited vitalism, the theory that the chemicals of living organisms are fundamentally different from those of inanimate matter. This insight was important for the development of organic chemistry. His discovery prompted Wöhler to write triumphantly to Jöns Jakob Berzelius:

- «I must tell you that I can make urea without the use of kidneys, either man or dog. Ammonium cyanate is urea.«

In fact, his second sentence was incorrect. Ammonium cyanate [NH4]+[OCN]− and urea CO(NH2)2 are two different chemicals with the same empirical formula CON2H4, which are in chemical equilibrium heavily favoring urea under standard conditions.[46] Regardless, with his discovery, Wöhler secured a place among the pioneers of organic chemistry.

Production[edit]

Urea is produced on an industrial scale: In 2012, worldwide production capacity was approximately 184 million tonnes.[47]

Industrial methods[edit]

For use in industry, urea is produced from synthetic ammonia and carbon dioxide. As large quantities of carbon dioxide are produced during the ammonia manufacturing process as a byproduct from hydrocarbons (predominantly natural gas, less often petroleum derivatives), or occasionally from coal (water shift reaction), urea production plants are almost always located adjacent to the site where the ammonia is manufactured. Although natural gas is both the most economical and the most widely available ammonia plant feedstock, plants using it do not produce quite as much carbon dioxide from the process as is needed to convert their entire ammonia output into urea. In recent years new technologies such as the KM-CDR process[48][49] have been developed to recover supplementary carbon dioxide from the combustion exhaust gases produced in the fired reforming furnace of the ammonia synthesis gas plant, allowing operators of stand-alone nitrogen fertilizer complexes to avoid the need to handle and market ammonia as a separate product and also to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere.

Synthesis[edit]

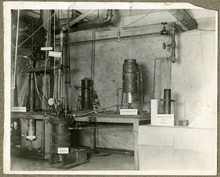

Urea plant using ammonium carbamate briquettes, Fixed Nitrogen Research Laboratory, ca. 1930

The basic process, developed in 1922, is also called the Bosch–Meiser urea process after its discoverers. Various commercial urea processes are characterized by the conditions under which urea forms and the way that unconverted reactants are further processed. The process consists of two main equilibrium reactions, with incomplete conversion of the reactants. The first is carbamate formation: the fast exothermic reaction of liquid ammonia with gaseous carbon dioxide (CO2) at high temperature and pressure to form ammonium carbamate ([NH4]+[NH2COO]−):[50]

- 2 NH3 + CO2 ⇌ [NH4]+[NH2COO]− (ΔH = −117 kJ/mol at 110 atm and 160 °C)[51]

The second is urea conversion: the slower endothermic decomposition of ammonium carbamate into urea and water:

- [NH4]+[NH2COO]− ⇌ CO(NH2)2 + H2O (ΔH = +15.5 kJ/mol at 160–180 °C)[51]

The overall conversion of NH3 and CO2 to urea is exothermic,[7] the reaction heat from the first reaction driving the second. Like all chemical equilibria, these reactions behave according to Le Chatelier’s principle, and the conditions that most favour carbamate formation have an unfavourable effect on the urea conversion equilibrium. The process conditions are, therefore, a compromise: the ill-effect on the first reaction of the high temperature (around 190 °C) needed for the second is compensated for by conducting the process under high pressure (140–175 bar), which favours the first reaction. Although it is necessary to compress gaseous carbon dioxide to this pressure, the ammonia is available from the ammonia plant in liquid form, which can be pumped into the system much more economically. To allow the slow urea formation reaction time to reach equilibrium a large reaction space is needed, so the synthesis reactor in a large urea plant tends to be a massive pressure vessel.

Because the urea conversion is incomplete, the product must be separated from unchanged ammonium carbamate. In early «straight-through» urea plants this was done by letting down the system pressure to atmospheric to let the carbamate decompose back to ammonia and carbon dioxide. Originally, because it was not economic to recompress the ammonia and carbon dioxide for recycle, the ammonia at least would be used for the manufacture of other products, for example ammonium nitrate or sulfate. (The carbon dioxide was usually wasted.) Later process schemes made recycling unused ammonia and carbon dioxide practical. This was accomplished by depressurizing the reaction solution in stages (first to 18 – 25 bar and then to 2 – 5 bar) and passing it at each stage through a steam-heated carbamate decomposer, then recombining the resultant carbon dioxide and ammonia in a falling-film carbamate condenser and pumping the carbamate solution into the previous stage.

Stripping concept[edit]

The «total recycle» concept has two main disadvantages. The first is the complexity of the flow scheme and, consequently, the amount of process equipment needed. The second is the amount of water recycled in the carbamate solution, which has an adverse effect on the equilibrium in the urea conversion reaction and thus on overall plant efficiency. The stripping concept, developed in the early 1960s by Stamicarbon in The Netherlands, addressed both problems. It also improved heat recovery and reuse in the process.

The position of the equilibrium in the carbamate formation/decomposition depends on the product of the partial pressures of the reactants. In the total recycle processes, carbamate decomposition is promoted by reducing the overall pressure, which reduces the partial pressure of both ammonia and carbon dioxide. It is possible, however, to achieve a similar effect without lowering the overall pressure—by suppressing the partial pressure of just one of the reactants. Instead of feeding carbon dioxide gas directly to the reactor with the ammonia, as in the total recycle process, the stripping process first routes the carbon dioxide through a stripper (a carbamate decomposer that operates under full system pressure and is configured to provide maximum gas-liquid contact). This flushes out free ammonia, reducing its partial pressure over the liquid surface and carrying it directly to a carbamate condenser (also under full system pressure). From there, reconstituted ammonium carbamate liquor passes directly to the reactor. That eliminates the medium-pressure stage of the total recycle process altogether.

The stripping concept was such a major advance that competitors such as Snamprogetti — now Saipem — (Italy), the former Montedison (Italy), Toyo Engineering Corporation (Japan), and Urea Casale (Switzerland) all developed versions of it. Today, effectively all new urea plants use the principle, and many total recycle urea plants have converted to a stripping process. No one has proposed a radical alternative to the approach. The main thrust of technological development today, in response to industry demands for ever larger individual plants, is directed at re-configuring and re-orientating major items in the plant to reduce size and overall height of the plant, and at meeting challenging environmental performance targets.[52][53]

Side reactions[edit]

It is fortunate that the urea conversion reaction is slow. If it were not it would go into reverse in the stripper. As it is, succeeding stages of the process must be designed to minimize residence times, at least until the temperature reduces to the point where the reversion reaction is very slow.

Two reactions produce impurities. Biuret is formed when two molecules of urea combine with the loss of a molecule of ammonia.

- 2 NH2CONH2 → NH2CONHCONH2 + NH3

Normally this reaction is suppressed in the synthesis reactor by maintaining an excess of ammonia, but after the stripper, it occurs until the temperature is reduced. Biuret is undesirable in fertilizer urea because it is toxic to crop plants, although to what extent depends on the nature of the crop and the method of application of the urea.[54] (Biuret is actually welcome in urea when is used as a cattle feed supplement).

Isocyanic acid HNCO and ammonia NH3 results from the thermal decomposition of ammonium cyanate [NH4]+[OCN]−, which is in chemical equilibrium with urea:

- CO(NH2)2 → [NH4]+[OCN]− → HNCO + NH3

This reaction is at its worst when the urea solution is heated at low pressure, which happens when the solution is concentrated for prilling or granulation (see below). The reaction products mostly volatilize into the overhead vapours, and recombine when these condense to form urea again, which contaminates the process condensate.

Corrosion[edit]

Ammonium carbamate solutions are notoriously corrosive to metallic construction materials, even more resistant forms of stainless steel – especially in the hottest parts of the plant such as the stripper. Historically corrosion has been minimized (although not eliminated) by continuous injection of a small amount of oxygen (as air) into the plant to establish and maintain a passive oxide layer on exposed stainless steel surfaces. Because the carbon dioxide feed is recovered from ammonia synthesis gas, it contains traces of hydrogen that can mingle with passivation air to form an explosive mixture if allowed to accumulate.

In the mid 1990s two duplex (ferritic-austenitic) stainless steels were introduced (DP28W, jointly developed by Toyo Engineering and Sumitomo Metals Industries[55] and Safurex, jointly developed by Stamicarbon and Sandvik Materials Technology (Sweden).[56][57]) These let manufactures drastically reduce the amount of passivation oxygen. In theory, they could operate with no oxygen.

Saipem now uses either zirconium stripper tubes, or bimetallic tubes with a titanium body (cheaper but less erosion-resistant) and a metallurgically bonded internal zirconium lining. These tubes are fabricated by ATI Wah Chang (USA) using its Omegabond technique.[58]

Finishing[edit]

Urea can be produced as prills, granules, pellets, crystals, and solutions.

Solid forms[edit]

For its main use as a fertilizer urea is mostly marketed in solid form, either as prills or granules. The advantage of prills is that, in general, they can be produced more cheaply than granules and that the technique was firmly established in industrial practice long before a satisfactory urea granulation process was commercialized. However, on account of the limited size of particles that can be produced with the desired degree of sphericity and their low crushing and impact strength, the performance of prills during bulk storage, handling and use is generally (with some exceptions[59]) considered inferior to that of granules.

High-quality compound fertilizers containing nitrogen co-granulated with other components such as phosphates have been produced routinely since the beginnings of the modern fertilizer industry, but on account of the low melting point and hygroscopic nature of urea it took courage to apply the same kind of technology to granulate urea on its own.[60] But at the end of the 1970s three companies began to develop fluidized-bed granulation.[61][62][63][64][65]

UAN solutions[edit]

In admixture, the combined solubility of ammonium nitrate and urea is so much higher than that of either component alone that it is possible to obtain a stable solution (known as UAN) with a total nitrogen content (32%) approaching that of solid ammonium nitrate (33.5%), though not, of course, that of urea itself (46%). Given the ongoing safety and security concerns surrounding fertilizer-grade solid ammonium nitrate, UAN provides a considerably safer alternative without entirely sacrificing the agronomic properties that make ammonium nitrate more attractive than urea as a fertilizer in areas with short growing seasons. It is also more convenient to store and handle than a solid product and easier to apply accurately to the land by mechanical means.[66][67]

Laboratory preparation[edit]

Ureas in the more general sense can be accessed in the laboratory by reaction of phosgene with primary or secondary amines:

- COCl2 + 4 RNH2 → (RNH)2CO + 2 [RNH3]+Cl−

These reactions proceed through an isocyanate intermediate. Non-symmetric ureas can be accessed by the reaction of primary or secondary amines with an isocyanate.

Urea can also be produced by heating ammonium cyanate to 60 °C.

- [NH4]+[OCN]− → (NH2)2CO

Historical process[edit]

Urea was first noticed by Herman Boerhaave in the early 18th century from evaporates of urine. In 1773, Hilaire Rouelle obtained crystals containing urea from human urine by evaporating it and treating it with alcohol in successive filtrations.[68] This method was aided by Carl Wilhelm Scheele’s discovery that urine treated by concentrated nitric acid precipitated crystals. Antoine François, comte de Fourcroy and Louis Nicolas Vauquelin discovered in 1799 that the nitrated crystals were identical to Rouelle’s substance and invented the term «urea.»[69][70] Berzelius made further improvements to its purification[71] and finally William Prout, in 1817, succeeded in obtaining and determining the chemical composition of the pure substance.[72] In the evolved procedure, urea was precipitated as urea nitrate by adding strong nitric acid to urine. To purify the resulting crystals, they were dissolved in boiling water with charcoal and filtered. After cooling, pure crystals of urea nitrate form. To reconstitute the urea from the nitrate, the crystals are dissolved in warm water, and barium carbonate added. The water is then evaporated and anhydrous alcohol added to extract the urea. This solution is drained off and evaporated, leaving pure urea.

Properties[edit]

Molecular and crystal structure[edit]

The urea molecule is planar. In solid urea, the oxygen center is engaged in two N–H–O hydrogen bonds. The resulting dense and energetically favourable hydrogen-bond network is probably established at the cost of efficient molecular packing: The structure is quite open, the ribbons forming tunnels with square cross-section. The carbon in urea is described as sp2 hybridized, the C-N bonds have significant double bond character, and the carbonyl oxygen is basic compared to, say, formaldehyde. Urea’s high aqueous solubility reflects its ability to engage in extensive hydrogen bonding with water.

By virtue of its tendency to form porous frameworks, urea has the ability to trap many organic compounds. In these so-called clathrates, the organic «guest» molecules are held in channels formed by interpenetrating helices composed of hydrogen-bonded urea molecules.[73] This behaviour can be used to separate mixtures, e.g., in the production of aviation fuel and lubricating oils, and in the separation of hydrocarbons.[citation needed]

As the helices are interconnected, all helices in a crystal must have the same molecular handedness. This is determined when the crystal is nucleated and can thus be forced by seeding. The resulting crystals have been used to separate racemic mixtures.[73]

Reactions[edit]

Urea is basic. As such it is protonates readily. It is also a Lewis base forming complexes of the type [M(urea)6]n+.

Molten urea decomposes into ammonia gas and isocyanic acid:

- CO(NH2)2 → NH3 + HNCO

Via isocyanic acid, heating urea converts to a range of condensation products including biuret NH2CONHCONH2, triuret NH2CONHCONHCONH2, guanidine HNC(NH2)2, and melamine:[74]

- CO(NH2)2 + HNCO → NH2CONHCONH2

- NH2CONHCONH2 + HNCO → NH2CONHCONHCONH2

In aqueous solution, urea slowly equilibrates with ammonium cyanate. This hydrolysis cogenerates isocyanic acid, which can carbamylate proteins.[75]

Urea reacts with malonic esters to make barbituric acids.

Urea may be use for obtaining deep eutectic solvents with sulfamic acid[76]

Etymology[edit]

Urea is New Latin, from French urée, from Ancient Greek οὖρον (ouron, «urine»), itself from Proto-Indo-European *h₂worsom.

See also[edit]

- Wöhler urea synthesis

- Thiourea

References[edit]

- ^ a b Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. pp. 416, 860–861. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

The compound H2N-CO-NH2 has the retained named ‘urea’, which is the preferred IUPAC name, (…). The systematic name is ‘carbonyl diamide’.

- ^ a b Yalkowsky, Samuel H.; He, Yan; Jain, Parijat (19 April 2016). Handbook of Aqueous Solubility Data. ISBN 9781439802465.

- ^ «Solubility of Various Compounds in Glycerine» (PDF). msdssearch.dow.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ Loeser E, DelaCruz M, Madappalli V (9 June 2011). «Solubility of Urea in Acetonitrile–Water Mixtures and Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation of Urea-Saturated Acetonitrile–Water Mixtures». Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 56 (6): 2909–2913. doi:10.1021/je200122b.

- ^ Calculated from 14−pKa. The value of pKa is given as 0.10 by the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 49th edition (1968–1969). A value of 0.18 is given by Williams, R. (24 October 2001). «pKa Data» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2003.

- ^ «Urea — Registration Dossier — ECHA». echa.europa.eu.

- ^ a b Meessen JH, Petersen H (2010). «Urea». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_333.

- ^ Duo et al., (1992). Can. J. Chem. Eng, 70, 1014–1020.

- ^ Durand, Erwann; Lecomte, Jérôme; Baréa, Bruno; Piombo, Georges; Dubreucq, Éric; Villeneuve, Pierre (1 December 2012). «Evaluation of deep eutectic solvents as new media for Candida antarctica B lipase catalyzed reactions». Process Biochemistry. Elsevier. 47 (12): 2081–2089. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2012.07.027. ISSN 1359-5113..

- ^ Carow, Colleen (14 November 2008). «Researchers develop urea fuel cell». Ohio University (Press release). Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Hama H, Kurokawa H, Kawano H, Ando R, Shimogori T, Noda H, Fukami K, Sakaue-Sawano A, Miyawaki A (August 2011). «Scale: a chemical approach for fluorescence imaging and reconstruction of transparent mouse brain». Nature Neuroscience. 14 (11): 1481–8. doi:10.1038/nn.2928. PMID 21878933. S2CID 28281721.

- ^ «UriSec 40 How it Works». Odan Laboratories. January 2009. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ «UriSec 40% Cream». Odan Laboratories. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ «Carbamide Peroxide Drops GENERIC NAME(S): CARBAMIDE PEROXIDE». WebMD. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ Crawford JH, McIntosh JF (1925). «The use of urea as a diuretic in advanced heart failure». Archives of Internal Medicine. New York. 36 (4): 530–541. doi:10.1001/archinte.1925.00120160088004.

- ^

Decaux G, Andres C, Gankam Kengne F, Soupart A (14 October 2010). «Treatment of euvolemic hyponatremia in the intensive care unit by urea» (PDF). Critical Care. 14 (5): R184. doi:10.1186/cc9292. PMC 3219290. PMID 20946646. - ^ Diggory PL (January 1971). «Induction of therapeutic abortion by intra-amniotic injection of urea». British Medical Journal. 1 (5739): 28–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5739.28. PMC 1794772. PMID 5539139.

- ^ Traynor J, Mactier R, Geddes CC, Fox JG (October 2006). «How to measure renal function in clinical practice». BMJ. 333 (7571): 733–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.38975.390370.7c. PMC 1592388. PMID 17023465.

- ^ Werk Michael; Albrecht Thomas; Meyer Dirk-Roelfs; Ahmed Mohammed Nabil; Behne Andrea; Dietz Ulrich; Eschenbach Götz; Hartmann Holger; Lange Christian (1 December 2012). «Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons Reduce Restenosis After Femoro-Popliteal Angioplasty». Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 5 (6): 831–840. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.971630. PMID 23192918.

- ^ Wöhrle, Jochen (1 October 2012). «Drug-Coated Balloons for Coronary and Peripheral Interventional Procedures». Current Cardiology Reports. 14 (5): 635–641. doi:10.1007/s11886-012-0290-x. PMID 22825918. S2CID 8879713.

- ^ Kolachalama, Vijaya B.; Shazly, Tarek; Vipul C. Chitalia; Lyle, Chimera; Azar, Dara A.; Chang, Gary H. (2 May 2019). «Intrinsic coating morphology modulates acute drug transfer in drug-coated balloon therapy». Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 6839. Bibcode:2019NatSR…9.6839C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-43095-9. PMC 6497887. PMID 31048704.

- ^ Heavy Duty Truck Systems. Cengage Learning. 2015. p. 1117. ISBN 9781305073623.

- ^ Chlorides—Advances in Research and Application: 2013 Edition. ScholarlyEditions. 2013. p. 77. ISBN 9781481674331.

- ^ «Lacura Multi Intensive Serum – Review – Excellent value for money – Lacura Multi Intensive Serum «Aqua complete»«. Dooyoo.co.uk. 19 June 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Knollenberg, Robert G. (March 1966). «Urea as an Ice Nucleant for Supercooled Clouds». American Meteorological Society. 23 (2): 197. Bibcode:1966JAtS…23..197K. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1966)023<0197:UAAINF>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Burch, Paula E. (13 November 1999). «Dyeing FAQ: What is urea for, in dyeing? Is it necessary?». All About Hand Dyeing. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ «Optical parametric oscillator using urea crystal». Google Patents.

- ^ Donaldson, William R.; Tang, C. L. (1984). «Urea optical parametric oscillator». Applied Physics Letters. AIP Publishing. 44 (1): 25–27. Bibcode:1984ApPhL..44…25D. doi:10.1063/1.94590.

- ^ Coombs A (27 October 2008). «Urea pollution turns tides toxic». Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2008.1190. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ International Chemical Safety Cards: UREA. cdc.gov

- ^ Sakami W, Harrington H (1963). «Amino acid metabolism». Annual Review of Biochemistry. 32 (1): 355–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.32.070163.002035. PMID 14144484.

- ^ «Urea». Imperial College London. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Walter F. Boron (2005). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approach. Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3. Page 837

- ^ Klein J, Blount MA, Sands JM (2011). «Urea Transport in the Kidney». Comprehensive Physiology. Comprehensive Physiology. Vol. 1. pp. 699–729. doi:10.1002/cphy.c100030. ISBN 9780470650714. PMID 23737200.

- ^ Section 1.9.2 (page 76) in: Jacki Bishop; Thomas, Briony (2007). Manual of Dietetic Practice. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3525-2.

- ^ PubChem. «urea cycle». pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Baumgartner M, Flöck M, Winter P, Luf W, Baumgartner W (2005). «Evaluation of flow injection analysis for determination of urea in sheep’s and cow’s milk» (PDF). Acta Veterinaria Hungarica. 50 (3): 263–71. doi:10.1556/AVet.50.2002.3.2. PMID 12237967. S2CID 42485569.

- ^ Greenan NS, Mulvaney RL, Sims GK (1995). «A microscale method for colorimetric determination of urea in soil extracts». Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis. 26 (15–16): 2519–2529. doi:10.1080/00103629509369465.

- ^

Boerhaave called urea «sal nativus urinæ» (the native, i.e., natural, salt of urine). See:- The first mention of urea is as «the essential salt of the human body» in: Peter Shaw and Ephraim Chambers, A New Method of Chemistry …, vol 2, (London, England: J. Osborn and T. Longman, 1727), page 193: Process LXXXVII.

- Boerhaave, Herman Elementa Chemicae …, volume 2, (Leipzig («Lipsiae»), (Germany): Caspar Fritsch, 1732), page 276.

- For an English translation of the relevant passage, see: Peter Shaw, A New Method of Chemistry …, 2nd ed., (London, England: T. Longman, 1741), page 198: Process CXVIII: The native salt of urine

- Lindeboom, Gerrit A. Boerhaave and Great Britain …, (Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1974), page 51.

- Backer, H. J. (1943) «Boerhaave’s Ontdekking van het Ureum» (Boerhaave’s discovery of urea), Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (Dutch Journal of Medicine), 87 : 1274–1278 (in Dutch).

- ^ Kurzer F, Sanderson PM (1956). «Urea in the History of Organic Chemistry». Journal of Chemical Education. 33 (9): 452–459. Bibcode:1956JChEd..33..452K. doi:10.1021/ed033p452.

- ^ «Why Pee is Cool – entry #5 – «How Pee Unites You With Rocks»«. Science minus details. 11 October 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Kurzer F, Sanderson PM (1956). «Urea in the History of Organic Chemistry». Journal of Chemical Education. 33 (9). p. 454. Bibcode:1956JChEd..33..452K. doi:10.1021/ed033p452.

- ^ Wöhler, Friedrich (1828) «Ueber künstliche Bildung des Harnstoffs» (On the artificial formation of urea), Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 88 (2) : 253–256. Available in English at Chem Team.

- ^

Nicolaou KC, Montagnon T (2008). Molecules That Changed The World. Wiley-VCH. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-527-30983-2. - ^

Gibb BC (April 2009). «Teetering towards chaos and complexity». Nature Chemistry. 1 (1): 17–8. Bibcode:2009NatCh…1…17G. doi:10.1038/nchem.148. PMID 21378787. - ^ Shorter, J. (1978). «The conversion of ammonium cyanate into urea—a saga in reaction mechanisms». Chemical Society Reviews. 7 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1039/CS9780700001.

- ^ «Market Study Urea». Ceresana.com. 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ Kishimoto S, Shimura R, Kamijo T (2008). MHI Proprietary Process for Reducing CO2 Emission and Increasing Urea Production. Nitrogen + Syngas 2008 International Conference and Exhibition. Moscow.

- ^ Al-Ansari, F (2008). «Carbon Dioxide Recovery at GPIC». Nitrogen+Syngas. 293: 36–38.

- ^ «Inorganic Chemicals: Ammonium Carbamate». Hillakomem.com. 2 October 2008. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ a b dadas, dadas. «Thermodynamics of the Urea Process». Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ Gevers B, Mennen J, Meessen J (2009). Avancore – Stamicarbon’s New Urea Plant Concept. Nitrogen+Syngas International Conference. Rome. pp. 113–125.

- ^ «World Class Urea Plants». Nitrogen+Syngas. 294: 29–38. 2008.

- ^ James, G.R.; Oomen, C.J.: «An Update on the Biuret Myth». Nitrogen 2001 International Conference, Tampa.

- ^ Nagashima, E. (2010). «Use of DP28W Reduces Passivation Air in Urea Plants». Nitrogen+Syngas. 304: 193–200.

- ^ Kangas, P.; Walden, B.; Berglund, G.; Nicholls, M. (to Sandvik AB): «Ferritic-Austenitic Stainless Steel and Use of the Steel». WO 95/00674 (1995).

- ^ Eijkenboom J, Wijk J (2008). «The Behaviour of Safurex». Nitrogen+Syngas. 295: 45–51.

- ^ Allegheny Technologies, Inc. (2012) «Increasing Urea Plant Capacity and Preventing Corrosion Related Downtime». ATI White Paper (8/27/2012)

- ^ «Prills or granules?». Nitrogen+Syngas. 292: 23–27. 2008.

- ^ «Ferrara refines its granulation process». Nitrogen 219, 51–56 (1996)

- ^ Bruynseels JP (1981). NSM’s Fluidized-Bed Urea Granulation Process Fertilizer Nitrogen. International Conference. London. pp. 277–288.

- ^ Nakamura, S. (2007) «The Toyo Urea Granulation Technology». 20th Arab Fertilizer International Annual Technical Conference, Tunisia.

- ^ «Fair Wind for FB Technology». Nitrogen+Syngas. 282: 40–47.

- ^ «Better product quality». Nitrogen+Syngas. 319: 52–61. 2012.

- ^ Baeder, Albert. «Rotoform Urea Particles – The Sustainable Premium Product» (PDF). UreaKnowHow.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ «Is UAN the Solution?». Nitrogen+Syngas. 287: 28–30. 2007.

- ^ Welch, I (2007). «Urea vs UAN». Nitrogen+Syngas. 289: 26–27.

- ^ Rouelle (1773) «Observations sur l’urine humaine, & sur celle de vache & de cheval, comparées ensemble» (Observations on human urine and on that of the cow and horse, compared to each other), Journal de Médecine, de Chirurgie et de Pharmacie, 40 : 451–468. Rouelle describes the procedure he used to separate urea from urine on pages 454–455.

- ^ Fourcroy and Vauquelin (1799) «Extrait d’un premier mémoire des cit. Fourcroy et Vaulquelin, pour servir à l’histoire naturelle, chimique et médicale de l’urine humaine, contenant quelques faits nouveaux sur son analyse et son altération spontanée» (Extract of a first memoir by citizens Fourcroy and Vauquelin, for use in the natural, chemical, and medical history of human urine, containing some new facts of its analysis and its spontaneous alteration), Annales de Chimie, 31 : 48–71. On page 69, urea is named «urée».

- ^ Fourcroy and Vauqeulin (1800) «Deuxième mémoire: Pour servir à l’histoire naturelle, chimique et médicale de l’urine humaine, dans lequel on s’occupe spécialement des propriétés de la matière particulière qui le caractérise,» (Second memoir: For use in the natural, chemical and medical history of human urine, in which one deals specifically with the properties of the particular material that characterizes it), Annales de Chimie, 32 : 80–112; 113–162. On page 91, urea is again named «urée».

- ^ Rosenfeld L (1999). Four Centuries of Clinical Chemistry. CRC Press. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-90-5699-645-1.

- ^ Prout W (1817). «Observations on the nature of some of the proximate principles of the urine; with a few remarks upon the means of preventing those diseases, connected with a morbid state of that fluid». Medico-Chirurgical Transactions. 8: 526–549. doi:10.1177/095952871700800123. PMC 2128986. PMID 20895332.

- ^ a b Worsch, Detlev; Vögtle, Fritz (2002). «Separation of enantiomers by clathrate formation». Topics in Current Chemistry. Springer-Verlag. pp. 21–41. doi:10.1007/bfb0003835. ISBN 3-540-17307-2.

- ^ Jozef Meessen (2012). «Urea». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_333.pub2.

- ^ Sun S, Zhou JY, Yang W, Zhang H (February 2014). «Inhibition of protein carbamylation in urea solution using ammonium-containing buffers». Analytical Biochemistry. 446: 76–81. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2013.10.024. PMC 4072244. PMID 24161613.

- ^ Kazachenko, Aleksandr S.; Issaoui, Noureddine; Medimagh, Mouna ; Yu. Fetisova, Olga; Berezhnaya, Yaroslava D.; Elsuf’ev, Evgeniy V.; Al-Dossary, Omar M.; Wojcik, Marek J.; Xiang, Zhouyang; Bousiakou, Leda G. Experimental and theoretical study of the sulfamic acid-urea deep eutectic solvent. (2022) Journal of Molecular Liquids, 363, art. no. 119859. DOI: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119859

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urea.

- Urea in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

|

||

|

||

| Names | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | urea , carbamide | |

| Preferred IUPAC name

Urea[1] |

||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Carbonyl diamide[1] |

||

Other names

|

||

| Identifiers | ||

|

CAS Number |

|

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

|

|

Beilstein Reference |

635724 | |

| ChEBI |

|

|

| ChEMBL |

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

|

| DrugBank |

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.286 |

|

| E number | E927b (glazing agents, …) | |

|

Gmelin Reference |

1378 | |

|

IUPHAR/BPS |

|

|

| KEGG |

|

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

|

| UNII |

|

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

|

InChI

|

||

|

SMILES

|

||

| Properties | ||

|

Chemical formula |

CO(NH2)2 | |

| Molar mass | 60.06 g/mol | |

| Appearance | White solid | |

| Density | 1.32 g/cm3 | |

| Melting point | 133 to 135 °C (271 to 275 °F; 406 to 408 K) | |

|

Solubility in water |

545 g/L (at 25 °C)[2] | |

| Solubility | 500 g/L glycerol[3]

50 g/L ethanol |

|

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.9[5] | |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

−33.4·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | ||

|

Dipole moment |

4.56 D | |

| ThermochemistryCRC Handbook | ||

|

Std enthalpy of |

−333.19 kJ/mol | |

|

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) |

−197.15 kJ/mol | |

| Pharmacology | ||

|

ATC code |

B05BC02 (WHO) D02AE01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | ||

| GHS labelling: | ||

|

Pictograms |

|

|

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

1 1 0 |

|

| Flash point | Non-flammable | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | ||

|

LD50 (median dose) |

8500 mg/kg (oral, rat) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | JT Baker | |

| Related compounds | ||

|

Related ureas |

Thiourea Hydroxycarbamide |

|

|

Related compounds |

|

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula CO(NH2)2. This amide has two amino groups (–NH2) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important role in the metabolism of nitrogen-containing compounds by animals and is the main nitrogen-containing substance in the urine of mammals. It is a colorless, odorless solid, highly soluble in water, and practically non-toxic (LD50 is 15 g/kg for rats).[6] Dissolved in water, it is neither acidic nor alkaline. The body uses it in many processes, most notably nitrogen excretion. The liver forms it by combining two ammonia molecules (NH3) with a carbon dioxide (CO2) molecule in the urea cycle. Urea is widely used in fertilizers as a source of nitrogen (N) and is an important raw material for the chemical industry.

In 1828 Friedrich Wöhler discovered that urea can be produced from inorganic starting materials, which was an important conceptual milestone in chemistry. This showed for the first time that a substance previously known only as a byproduct of life could be synthesized in the laboratory without biological starting materials, thereby contradicting the widely held doctrine of vitalism, which stated that only living organisms could produce the chemicals of life.

Uses[edit]

Agriculture[edit]

A plant in Bangladesh that produces urea fertilizer.

More than 90% of world industrial production of urea is destined for use as a nitrogen-release fertilizer.[7] Urea has the highest nitrogen content of all solid nitrogenous fertilizers in common use. Therefore, it has a low transportation cost per unit of nitrogen nutrient. The most common impurity of synthetic urea is biuret, which impairs plant growth. Urea breaks down in the soil to give ammonium. The ammonium is taken up by the plant. In some soils, the ammonium is oxidized by bacteria to give nitrate, which is also a plant nutrient. The loss of nitrogenous compounds to the atmosphere and runoff is both wasteful and environmentally damaging. For this reason, urea is sometimes pretreated or modified to enhance the efficiency of its agricultural use. One such technology is controlled-release fertilizers, which contain urea encapsulated in an inert sealant. Another technology is the conversion of urea into derivatives, such as formaldehyde, which degrades into ammonia at a pace matching plants’ nutritional requirements.

Resins[edit]

Urea is a raw material for the manufacture of two main classes of materials: urea-formaldehyde resins and urea-melamine-formaldehyde used mostly in wood based panels such as particleboard,

fiberboard and plywood, among others.

Explosives[edit]

Urea can be used to make urea nitrate, a high explosive that is used industrially and as part of some improvised explosive devices.

Automobile systems[edit]

Urea is used in Selective Non-Catalytic Reduction (SNCR) and Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) reactions to reduce the NOx pollutants in exhaust gases from combustion from diesel, dual fuel, and lean-burn natural gas engines. The BlueTec system, for example, injects a water-based urea solution into the exhaust system. Ammonia (NH3) first produced by the hydrolysis of urea reacts with nitrogen oxides (NOx) and is converted into nitrogen gas (N2) and water within the catalytic converter. The conversion of noxious NOx to innocuous N2 is described by the following simplified global equation:[8]

- 4 NO + 4 NH3 + O2 → 4 N2 + 6 H2O

When urea is used, a pre-reaction (hydrolysis) occurs to first convert it to ammonia:

- CO(NH2)2 + H2O → 2 NH3 + CO2

Being a solid highly soluble in water (545 g/L at 25 °C),[2] urea is much easier and safer to handle and store than the more irritant, caustic and hazardous ammonia (NH3), so it is the reactant of choice. Trucks and cars using these catalytic converters need to carry a supply of diesel exhaust fluid, also sold as AdBlue, a solution of urea in water.

Laboratory uses[edit]

Urea in concentrations up to 10 M is a powerful protein denaturant as it disrupts the noncovalent bonds in the proteins. This property can be exploited to increase the solubility of some proteins.

A mixture of urea and choline chloride is used as a deep eutectic solvent (DES), a substance similar to ionic liquid. When used in a deep eutectic solvent, urea gradually denatures the proteins that are solubilized.[9]

Urea can in principle serve as a hydrogen source for subsequent power generation in fuel cells. Urea present in urine/wastewater can be used directly (though bacteria normally quickly degrade urea). Producing hydrogen by electrolysis of urea solution occurs at a lower voltage (0.37 V) and thus consumes less energy than the electrolysis of water (1.2 V).[10]

Urea in concentrations up to 8 M can be used to make fixed brain tissue transparent to visible light while still preserving fluorescent signals from labeled cells. This allows for much deeper imaging of neuronal processes than previously obtainable using conventional one photon or two photon confocal microscopes.[11]

Medical use[edit]

Urea-containing creams are used as topical dermatological products to promote rehydration of the skin. Urea 40% is indicated for psoriasis, xerosis, onychomycosis, ichthyosis, eczema, keratosis, keratoderma, corns, and calluses. If covered by an occlusive dressing, 40% urea preparations may also be used for nonsurgical debridement of nails. Urea 40% «dissolves the intercellular matrix»[12][13] of the nail plate. Only diseased or dystrophic nails are removed, as there is no effect on healthy portions of the nail.[citation needed] This drug (as carbamide peroxide) is also used as an earwax removal aid.[14]

Urea has also been studied as a diuretic. It was first used by Dr. W. Friedrich in 1892.[15] In a 2010 study of ICU patients, urea was used to treat euvolemic hyponatremia and was found safe, inexpensive, and simple.[16]

Like saline, urea has been injected into the uterus to induce abortion, although this method is no longer in widespread use.[17]

The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) test is a measure of the amount of nitrogen in the blood that comes from urea. It is used as a marker of renal function, though it is inferior to other markers such as creatinine because blood urea levels are influenced by other factors such as diet, dehydration,[18] and liver function.

Urea has also been studied as an excipient in Drug-coated Balloon (DCB) coating formulation to enhance local drug delivery to stenotic blood vessels.[19][20] Urea, when used as an excipient in small doses (~3 μg/mm2) to coat DCB surface was found to form crystals that increase drug transfer without adverse toxic effects on vascular endothelial cells.[21]

Urea labeled with carbon-14 or carbon-13 is used in the urea breath test, which is used to detect the presence of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in the stomach and duodenum of humans, associated with peptic ulcers. The test detects the characteristic enzyme urease, produced by H. pylori, by a reaction that produces ammonia from urea. This increases the pH (reduces the acidity) of the stomach environment around the bacteria. Similar bacteria species to H. pylori can be identified by the same test in animals such as apes, dogs, and cats (including big cats).

Miscellaneous uses[edit]

- An ingredient in diesel exhaust fluid (DEF), which is 32.5% urea and 67.5% de-ionized water. DEF is sprayed into the exhaust stream of diesel vehicles to break down dangerous NOx emissions into harmless nitrogen and water.

- A component of animal feed, providing a relatively cheap source of nitrogen to promote growth

- A non-corroding alternative to rock salt for road de-icing.[22] It is often the main ingredient of pet friendly salt substitutes although it is less effective than traditional rock salt or calcium chloride.[23]

- A main ingredient in hair removers such as Nair and Veet

- A browning agent in factory-produced pretzels

- An ingredient in some skin cream,[24] moisturizers, hair conditioners, and shampoos

- A cloud seeding agent, along with other salts[25]

- A flame-proofing agent, commonly used in dry chemical fire extinguisher charges such as the urea-potassium bicarbonate mixture

- An ingredient in many tooth whitening products

- An ingredient in dish soap

- Along with diammonium phosphate, as a yeast nutrient, for fermentation of sugars into ethanol

- A nutrient used by plankton in ocean nourishment experiments for geoengineering purposes

- As an additive to extend the working temperature and open time of hide glue

- As a solubility-enhancing and moisture-retaining additive to dye baths for textile dyeing or printing[26]

- As an optical parametric oscillator in nonlinear optics[27][28]

Adverse effects[edit]

Urea can be irritating to skin, eyes, and the respiratory tract. Repeated or prolonged contact with urea in fertilizer form on the skin may cause dermatitis.[citation needed]

High concentrations in the blood can be damaging. Ingestion of low concentrations of urea, such as are found in typical human urine, are not dangerous with additional water ingestion within a reasonable time-frame. Many animals (e.g. camels, rodents or dogs) have a much more concentrated urine which may contain a higher urea amount than normal human urine.

Urea can cause algal blooms to produce toxins, and its presence in the runoff from fertilized land may play a role in the increase of toxic blooms.[29]

The substance decomposes on heating above melting point, producing toxic gases, and reacts violently with strong oxidants, nitrites, inorganic chlorides, chlorites and perchlorates, causing fire and explosion.[30]

Physiology[edit]

Amino acids from ingested food that are used for the synthesis of proteins and other biological substances — or produced from catabolism of muscle protein — are oxidized by the body as an alternative source of energy, yielding urea and carbon dioxide.[31] The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase; the amino group is then fed into the urea cycle. The first step in the conversion of amino acids from protein into metabolic waste in the liver is removal of the alpha-amino nitrogen, which results in ammonia. Because ammonia is toxic, it is excreted immediately by fish, converted into uric acid by birds, and converted into urea by mammals.[32]

Ammonia (NH3) is a common byproduct of the metabolism of nitrogenous compounds. Ammonia is smaller, more volatile and more mobile than urea. If allowed to accumulate, ammonia would raise the pH in cells to toxic levels. Therefore, many organisms convert ammonia to urea, even though this synthesis has a net energy cost. Being practically neutral and highly soluble in water, urea is a safe vehicle for the body to transport and excrete excess nitrogen.

Urea is synthesized in the body of many organisms as part of the urea cycle, either from the oxidation of amino acids or from ammonia. In this cycle, amino groups donated by ammonia and L-aspartate are converted to urea, while L-ornithine, citrulline, L-argininosuccinate, and L-arginine act as intermediates. Urea production occurs in the liver and is regulated by N-acetylglutamate. Urea is then dissolved into the blood (in the reference range of 2.5 to 6.7 mmol/L) and further transported and excreted by the kidney as a component of urine. In addition, a small amount of urea is excreted (along with sodium chloride and water) in sweat.

In water, the amine groups undergo slow displacement by water molecules, producing ammonia, ammonium ion, and bicarbonate ion. For this reason, old, stale urine has a stronger odor than fresh urine.

Humans[edit]

The cycling of and excretion of urea by the kidneys is a vital part of mammalian metabolism. Besides its role as carrier of waste nitrogen, urea also plays a role in the countercurrent exchange system of the nephrons, that allows for reabsorption of water and critical ions from the excreted urine. Urea is reabsorbed in the inner medullary collecting ducts of the nephrons,[33] thus raising the osmolarity in the medullary interstitium surrounding the thin descending limb of the loop of Henle, which makes the water reabsorb.

By action of the urea transporter 2, some of this reabsorbed urea eventually flows back into the thin descending limb of the tubule,[34] through the collecting ducts, and into the excreted urine. The body uses this mechanism, which is controlled by the antidiuretic hormone, to create hyperosmotic urine — i.e., urine with a higher concentration of dissolved substances than the blood plasma. This mechanism is important to prevent the loss of water, maintain blood pressure, and maintain a suitable concentration of sodium ions in the blood plasma.

The equivalent nitrogen content (in grams) of urea (in mmol) can be estimated by the conversion factor 0.028 g/mmol.[35] Furthermore, 1 gram of nitrogen is roughly equivalent to 6.25 grams of protein, and 1 gram of protein is roughly equivalent to 5 grams of muscle tissue. In situations such as muscle wasting, 1 mmol of excessive urea in the urine (as measured by urine volume in litres multiplied by urea concentration in mmol/L) roughly corresponds to a muscle loss of 0.67 gram.

Other species[edit]

In aquatic organisms the most common form of nitrogen waste is ammonia, whereas land-dwelling organisms convert the toxic ammonia to either urea or uric acid. Urea is found in the urine of mammals and amphibians, as well as some fish. Birds and saurian reptiles have a different form of nitrogen metabolism that requires less water, and leads to nitrogen excretion in the form of uric acid. Tadpoles excrete ammonia, but shift to urea production during metamorphosis. Despite the generalization above, the urea pathway has been documented not only in mammals and amphibians, but in many other organisms as well, including birds, invertebrates, insects, plants, yeast, fungi, and even microorganisms.[36]

Analysis[edit]

Urea is readily quantified by a number of different methods, such as the diacetyl monoxime colorimetric method, and the Berthelot reaction (after initial conversion of urea to ammonia via urease). These methods are amenable to high throughput instrumentation, such as automated flow injection analyzers[37] and 96-well micro-plate spectrophotometers.[38]

[edit]

Ureas describes a class of chemical compounds that share the same functional group, a carbonyl group attached to two organic amine residues: R1R2N−C(=O)−NR3R4, where R1, R2, R3 and R4 groups are hydrogen (–H), organyl or other groups. Examples include carbamide peroxide, allantoin, and hydantoin. Ureas are closely related to biurets and related in structure to amides, carbamates, carbodiimides, and thiocarbamides.

History[edit]

Urea was first discovered in urine in 1727 by the Dutch scientist Herman Boerhaave,[39] although this discovery is often attributed to the French chemist Hilaire Rouelle as well as William Cruickshank.[40]

Boerhaave used the following steps to isolate urea:[41][42]

- Boiled off water, resulting in a substance similar to fresh cream

- Used filter paper to squeeze out remaining liquid

- Waited a year for solid to form under an oily liquid

- Removed the oily liquid

- Dissolved the solid in water

- Used recrystallization to tease out the urea

In 1828, the German chemist Friedrich Wöhler obtained urea artificially by treating silver cyanate with ammonium chloride.[43][44][45]

- AgNCO + [NH4]Cl → CO(NH2)2 + AgCl

This was the first time an organic compound was artificially synthesized from inorganic starting materials, without the involvement of living organisms. The results of this experiment implicitly discredited vitalism, the theory that the chemicals of living organisms are fundamentally different from those of inanimate matter. This insight was important for the development of organic chemistry. His discovery prompted Wöhler to write triumphantly to Jöns Jakob Berzelius:

- «I must tell you that I can make urea without the use of kidneys, either man or dog. Ammonium cyanate is urea.«

In fact, his second sentence was incorrect. Ammonium cyanate [NH4]+[OCN]− and urea CO(NH2)2 are two different chemicals with the same empirical formula CON2H4, which are in chemical equilibrium heavily favoring urea under standard conditions.[46] Regardless, with his discovery, Wöhler secured a place among the pioneers of organic chemistry.

Production[edit]