Как правильно пишется словосочетание «моющие средства»

- Как правильно пишется слово «моющий»

- Как правильно пишется слово «средство»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: приобретший — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к словосочетанию «моющее средство»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «моющие средства»

Предложения со словосочетанием «моющие средства»

- Синтетические моющие средства, химический состав которых отличается от мыла, оказались, тем не менее, логическим продолжением мыльного производства, его следующим технологическим поколением.

- Следует вымыть стекло, используя специальные моющие средства или содовый раствор, а затем насухо вытереть его мягкой, хорошо впитывающей влагу салфеткой.

- В тот день я чистила детский стульчик моей годовалой дочери и поставила на него бутылку универсального моющего средства.

- (все предложения)

Сочетаемость слова «средства»

- денежные средства

транспортное средство

основные средства - средства массовой информации

средства производства

средства связи - использование средств

сбор средств

часть средств - средства позволяют

средство помогло

средство подействовало - являться средством

использовать подручные средства

не иметь средств - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение словосочетания «моющее средство»

-

Моющее средство, детергент (лат. detergeo — «мою») — средство из арсенала бытовой химии, служащее для очистки чего-либо от загрязнения. Основным действующим компонентом является поверхностно-активное вещество (ПАВ) или смесь ПАВ. (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания МОЮЩЕЕ СРЕДСТВО

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «средства»

- Грандиозные вещи делаются грандиозными средствами. Одна природа делает великое даром.

- Старость, скромные средства и красные подслеповатые глаза не создают в любви благоприятную ситуацию.

- При оценке любой партии важны не одни конечные цели, но и средства и пути их достижения… Хорошие, правильные средства, основанные на хороших началах, возвышающие человека, могут сами по себе привести к хорошим целям, а одни цели, без правильных средств, — остаются в лучшем случае в воздухе.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

Моющее средство, детергент (лат. detergeo — «мою») — средство из арсенала бытовой химии, служащее для очистки чего-либо от загрязнения. Основным действующим компонентом является поверхностно-активное вещество (ПАВ) или смесь ПАВ.

Все значения словосочетания «моющее средство»

-

Синтетические моющие средства, химический состав которых отличается от мыла, оказались, тем не менее, логическим продолжением мыльного производства, его следующим технологическим поколением.

-

Следует вымыть стекло, используя специальные моющие средства или содовый раствор, а затем насухо вытереть его мягкой, хорошо впитывающей влагу салфеткой.

-

В тот день я чистила детский стульчик моей годовалой дочери и поставила на него бутылку универсального моющего средства.

- (все предложения)

- стиральные машины

- (ещё синонимы…)

- средство

- посуда

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- моющие средства

- моющий пылесос

- запах моющего средства

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- денежные средства

- средства массовой информации

- использование средств

- средства позволяют

- являться средством

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- Разбор по составу слова «моющий»

- Разбор по составу слова «средство»

- Как правильно пишется слово «моющий»

- Как правильно пишется слово «средство»

→

моющее — прилагательное, именительный п., ср. p., ед. ч.

↳

моющее — прилагательное, винительный п., ср. p., ед. ч.

→

моющее — прилагательное, именительный п., ср. p., ед. ч.

↳

моющее — прилагательное, винительный п., ср. p., ед. ч.

↳

моющее — причастие, именительный п., ср. p., наст. вр., ед. ч.

↳

моющее — причастие, винительный п., ср. p., наст. вр., ед. ч.

Часть речи: инфинитив — мыть

Часть речи: прилагательное

Действительное причастие:

Часть речи: кр. причастие

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Морфологический разбор «моющее»

На чтение 5 мин. Опубликовано 23.12.2020

В данной статье мы рассмотрим слово «моющее». В зависимости от контекста, оно может быть именем прилагательным или причастием. Ниже мы подробно разберём каждый из этих случаев, дадим морфологический разбор слова и укажем его возможные синтаксические роли.

Если вы хотите разобрать другое слово, то укажите его в форме поиска.

«Моющее» (имя прилагательное)

Морфологический разбор имени прилагательного

- I Часть речи: имя прилагательное;

- IIНачальная форма: моющий — единственное число, мужской род, именительный падеж;

- IIIМорфологические признаки:

- А. Постоянные признаки:

- Разряд по значению: относительное

- Б. Непостоянные признаки:

-

- средний род, единственное число, полная форма, положительная степень

- именительный или винительный падеж

- IV Синтаксическая роль:

1) моющее – средний род, единственное число, полная форма, положительная степень, именительный падеж

определение

именная часть сказуемого

2) моющее – средний род, единственное число, полная форма, положительная степень, винительный падеж

Склонение имени прилагательного по падежам

| Падеж | Мужской род | Средний род | Женский род | Множественное число |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Именительный падеж | Какой?моющий | Какое?моющее | Какая?моющая | Какие?моющие |

| Родительный падеж | Какого?моющего | Какого?моющего | Какой?моющей | Каких?моющих |

| Дательный падеж | Какому?моющему | Какому?моющему | Какой?моющей | Каким?моющим |

| Винительный падеж | Какого? Какой?моющего, моющий | Какого? Какое?моющее | Какую?моющую | Каких? Какие?моющие, моющих |

| Творительный падеж | Каким?моющим | Каким?моющим | Какой?моющею, моющей | Какими?моющими |

| Предложный падеж | О каком?моющем | О каком?моющем | О какой?моющей | О каких?моющих |

«Моющее» (причастие)

Значение слова «мыть» по словарю С. И. Ожегова

- Добывать (обычно о золоте), промывая песок, землю

- Обливать, окатывать; размывать

- Очищать от грязи при помощи воды, воды с мылом, какой-нибудь жидкости

Морфологический разбор причастия

- I Часть речи: причастие;

- IIНачальная форма: мыть;

- IIIМорфологические признаки:

- А. Постоянные признаки:

- действительное

- невозвратное

- переходное

- настоящее время

- несовершенный вид

- Б. Непостоянные признаки:

-

- средний род, единственное число, полная форма

- именительный или винительный падеж

- IV Синтаксическая роль: в зависимости от контекста, может быть следующими членами предложения:

1) моющее – средний род, единственное число, полная форма, именительный падеж

2) моющее – средний род, единственное число, полная форма, винительный падеж

Времена и падежи действительных причастий (несовершенный вид)

| Падеж | Время | Мужской род | Средний род | Женский род | Множественное число |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| именительный | прошедшее | Что делавший?мывший | Что делавшее?мывшее | Что делавшая?мывшая | Что делавшие?мывшие |

| настоящее | Что делающий?моющий | Что делающее?моющее | Что делающая?моющая | Что делающие?моющие | |

| родительный | прошедшее | Что делавшего?мывшего | Что делавшего?мывшего | Что делавшей?мывшей | Что делающих?мывших |

| настоящее | Что делающего?моющего | Что делающего?моющего | Что делающей?моющей | Что делающих?моющих | |

| дательный | прошедшее | Что делавшему?мывшему | Что делавшему?мывшему | Что делавшей?мывшей | Что делавшим?мывшим |

| настоящее | Что делающему?моющему | Что делающему?моющему | Что делающей?моющей | Что делающим?моющим | |

| винительный | прошедшее | Что делавшего? Что делавший?мывшего, мывший | Что делавшего? Что делавшее?мывшее | Что делавшую?мывшую | Что делавших? Что делавшие?мывшие, мывших |

| настоящее | Что делающего? Что делающий?моющего, моющий | Что делающего? Что делающее?моющее | Что делающую?моющую | Что делающих? Что делающие?моющие, моющих | |

| творительный | прошедшее | Что делавшим?мывшим | Что делавшим?мывшим | Что делавшей?мывшею, мывшей | Что делавшими?мывшими |

| настоящее | Что делающим?моющим | Что делающим?моющим | Что делающей?моющею, моющей | Что делающими?моющими | |

| предложный | прошедшее | О что делавшем?мывшем | О что делавшем?мывшем | О что делавшей?мывшей | О что делавших?мывших |

| настоящее | О что делающем?моющем | О что делающем?моющем | О что делающей?моющей | О что делающих?моющих |

Разобрать другое слово

Введите слово для разбора:Найти

Относительными называются прилагательные, которые обозначают:

- из чего сделан предмет: деревянный стул (стул из дерева), стеклянная ваза (ваза из стекла), малиновое варенье (варенье из малины), бетонная стена (стена из бетона);

- для кого или чего предназначен предмет: детский магазин (магазин для детей), садоводческий фестиваль (фестиваль для садоводов), вязальные спицы (спицы для вязания);

- отношение предмета ко времени: осеннее похолодание (похолодание осенью), вечернее чаепитие (чаепитие вечером);

- отношение предмета к месту: горный хребет (хребет гор), лесной цветок (цветок леса);

- отношение предмета к области деятельности: футбольный журнал (журнал про футбол).

Относительные прилагательные не имеют антонимов и синонимов, степеней сравнения и кратких форм.

Отвечают на вопросы «какой?», «какая?», «какое?», «какие?».

Полные прилагательные отвечают на вопросы «какой?», «какая?», «какое?», «какие?» и могут склоняться по родам, числам и падежам.

Качественные и относительные прилагательные: отвечает на вопросы «какой?», «какая?», «какое?», «какие?»

Притяжательные прилагательные: отвечает на вопросы «чей?», «чья?», «чьё?», «чьи?»

Качественные и относительные прилагательные: отвечает на вопросы «какого?», «какой?», «какое?», «какую?», «каких?», «какие?»

Притяжательные прилагательные: отвечает на вопросы «чьего?», «чей?», «чьё?», «чью?», «чьих?», «чьи?»

Причастия несовершенного вида образуются от глаголов несовершенного вида и обозначают действие, которое ещё не завершено.

Несовершенного вида могут быть действительные и страдательные причастия прошедшего и настоящего времени:

| Действительное | Страдательное | |

|---|---|---|

| Прошедшее время | сотрудник, работавший допоздна — сотрудник, который (что делал?) работал допоздна | взрыв, виденный издалека — взрыв, который (что делали?) видели издалека |

| Настоящее время | сотрудник, работающий допоздна — сотрудник, который (что делает?) работает допоздна | взрыв, видимый издалека — взрыв, который (что делают?) видят издалека |

Невозвратные причастия образуются от невозвратных глаголов (без постфикса -ся (-сь)). Могут быть:

- переходными и непереходными: мама, одевающая дочку (перех.); собака, идущая на поводке (неперех.);

- действительными и страдательными: дети, гуляющие в парке (действ.); обед, приготовленный бабушкой (страд.).

Переходные причастия образуются от переходных глаголов, обозначают, что действие направлено на другой объект.

Могут сочетаться с существительными и местоимениями в винительном падеже (вопросы «кого?», «что?») без предлога.

Действительные причастия обозначают признак предмета, который сам совершил действие.

Могут быть:

- прошедшего и настоящего времени: мальчик, решающий задачу (прош. вр.); мальчик, решивший задачу (наст. вр.);

- совершенного (только в прошедшем времени) и несовершенного вида: спортсмен, пробежавший по дорожке (сов.); спортсмен, бежавший по дорожке (несов.);

- переходными и непереходными: мама, купившая (что?) мороженое (перех.); девочка, идущая в школу (неперех.).

Действительные причастия не могут образовывать краткую форму.

Полные причастия отвечают на вопросы «какой?», «какая?», «какое?», «какие?», бывают страдательными и действительными:

- действительные: папа (какой?), объясняющий задачу; бабушка (какая?), читавшая газету; дети (какие?), играющие в догонялки;

- страдательные: клубника (какая?), выращенная на грядке; трава (какая?), скошенная газонокосилкой; девочки (какие?), одетые нарядно; звук (какой?) слышимый издалека.

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions.[1] There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are more soluble in hard water, because the polar sulfonate (of detergents) is less likely than the polar carboxylate (of soap) to bind to calcium and other ions found in hard water.

Definitions[edit]

Look up detergent in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

The word detergent is derived from the Latin adjective detergens, from the verb detergere, meaning to wipe or polish off. Detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions.[1] However, conventionally, detergent is used to mean synthetic cleaning compounds as opposed to soap (a salt of the natural fatty acid), even though soap is also a detergent in the true sense.[2] In domestic contexts, the term detergent refers to household cleaning products such as laundry detergent or dish detergent, which are in fact complex mixture of different compounds, not all of which are by themselves detergents.

Detergency is the ability to remove unwanted substances termed ‘soils’ from a substrate (e.g clothing).[3]

Structure and properties[edit]

Detergents are a group of compounds with an amphiphilic structure, where each molecule has a hydrophilic (polar) head and a long hydrophobic (non-polar) tail. The hydrophobic portion of these molecules may be straight- or branched-chain hydrocarbons, or it may have a steroid structure. The hydrophilic portion is more varied, they may be ionic or non-ionic, and can range from a simple or a relatively elaborate structure.[4] Detergents are surfactants since they can decrease the surface tension of water. Their dual nature facilitates the mixture of hydrophobic compounds (like oil and grease) with water. Because air is not hydrophilic, detergents are also foaming agents to varying degrees.

Detergent molecules aggregate to form micelles, which makes them soluble in water. The hydrophobic group of the detergent is the main driving force of micelle formation, its aggregation forms the hydrophobic core of the micelles. The micelle can remove grease, protein or soiling particles. The concentration at which micelles start to form is the critical micelle concentration (CMC), and the temperature at which the micelles further aggregate to separate the solution into two phases is the cloud point when the solution becomes cloudy and detergency is optimal.[4]

Detergents work better in an alkaline pH. The properties of detergents are dependent on the molecular structure of the monomer. The ability to foam may be determined by the head group, for example anionic surfactants are high-foaming, while nonionic surfactants may be non-foaming or low-foaming.[5]

Chemical classifications of detergents[edit]

Detergents are classified into four broad groupings, depending on the electrical charge of the surfactants.[6]

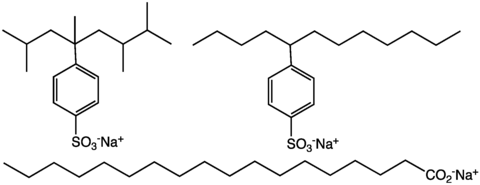

Anionic detergents[edit]

Typical anionic detergents are alkylbenzene sulfonates. The alkylbenzene portion of these anions is lipophilic and the sulfonate is hydrophilic. Two varieties have been popularized, those with branched alkyl groups and those with linear alkyl groups. The former were largely phased out in economically advanced societies because they are poorly biodegradable.[7]

Anionic detergents is the most common form of detergents, and an estimated 6 billion kilograms of anionic detergents are produced annually for the domestic markets.

Bile acids, such as deoxycholic acid (DOC), are anionic detergents produced by the liver to aid in digestion and absorption of fats and oils.

Cationic detergents[edit]

Cationic detergents are similar to anionic ones, but quaternary ammonium replaces the hydrophilic anionic sulfonate group. The ammonium sulfate center is positively charged.[7] Cationic surfactants generally have poor detergency.

Non-ionic detergents[edit]

Non-ionic detergents are characterized by their uncharged, hydrophilic headgroups. Typical non-ionic detergents are based on polyoxyethylene or a glycoside. Common examples of the former include Tween, Triton, and the Brij series. These materials are also known as ethoxylates or PEGylates and their metabolites, nonylphenol. Glycosides have a sugar as their uncharged hydrophilic headgroup. Examples include octyl thioglucoside and maltosides. HEGA and MEGA series detergents are similar, possessing a sugar alcohol as headgroup.

Amphoteric detergents[edit]

Amphoteric or zwitterionic detergents have zwitterions within a particular pH range, and possess a net zero charge arising from the presence of equal numbers of +1 and −1 charged chemical groups. Examples include CHAPS.

History[edit]

Soap is known to be have been used as a surfactant for washing clothes since the Sumerian time in 2,500 B.C.[8] In ancient Egypt, soda was used as a wash additive. In the 19th century, synthetic surfactants began to be created, for example from olive oil.[9] Sodium silicate (water glass) was used in soap-making in the United States in the 1860s,[10] and in 1876, Henkel sold a sodium silicate-based product that can be used with soap and marketed as a «universal detergent» (Universalwaschmittel) in Germany. Soda was then mixed with sodium silicate to produce Germany’s first brand name detergent Bleichsoda.[11] In 1907 Henkel also added a bleaching agent sodium perborate to launch the first ‘self-acting’ laundry detergent Persil to eliminate the laborious rubbing of laundry by hand.[12]

During the First World War, there was a shortage of oils and fats needed to make soap. In order find alternatives for soap, synthetic detergents were made in Germany by chemists using raw material derived from coal tar.[13][14][9] These early products, however, did not provide sufficient detergency. In 1928, effective detergent was made through the sulfation of fatty alcohol, but large-scale production was not feasible until low-cost fatty alcohols become available in the early 1930s.[15] The synthetic detergent created was more effective and less likely to form scum than soap in hard water, and can also eliminate acid and alkaline reactions and decompose dirt. Commercial detergent products with fatty alcohol sulphates began to be sold, initially in 1932 in Germany by Henkel.[15] In the United States, detergents were sold in 1933 by Procter & Gamble (Dreft) primarily in areas with hard water.[14] However, sales in the US grew slowly until the introduction of ‘built’ detergents with the addition of effective phosphate builder developed in the early 1940s.[14] The builder improves the performance of the surfactants by softening the water through the chelation of calcium and magnesium ions, helping to maintain an alkaline pH, as well as dispersing and keeping the soiling particles in solution.[16] The development of the petrochemical industry after the Second World War also yielded material for the production of a range of synthetic surfactants, and alkylbenzene sulfonates became the most important detergent surfactants used.[17] By the 1950s, laundry detergents had become widespread, and largely replaced soap for cleaning clothes in developed countries.[15]

Over the years, many types of detergents have been developed for a variety of purposes, for example, low-sudsing detergents for use in front-loading washing machines, heavy-duty detergents effective in removing grease and dirt, all-purpose detergents and specialty detergents.[14][18] They become incorporated in various products outside of laundry use, for example in dishwasher detergents, shampoo, toothpaste, industrial cleaners, and in lubricants and fuels to reduce or prevent the formation of sludge or deposits.[19] The formulation of detergent products may include bleach, fragrances, dyes and other additives. The use of phosphates in detergent, however, led to concerns over nutrient pollution and demand for changes to the formulation of the detergents.[20] Concerns were also raised over the use of surfactants such as branched alkylbenzene sulfonate (tetrapropylenebenzene sulfonate) that lingers in the environment, which led to their replacement by surfactants that are more biodegradable, such as linear alkylbenzene sulfonate.[15][17] Developments over the years have included the use of enzymes, substitutes for phosphates such as zeolite A and NTA, TAED as bleach activator, sugar-based surfactants which are biodegradable and milder to skin, and other green friendly products, as well as changes to the form of delivery such as tablets, gels and pods.[21][22]

Major applications of detergents[edit]

Household cleaning[edit]

One of the largest applications of detergents is for household and shop cleaning including dish washing and washing laundry. These detergents are commonly available as powders or concentrated solutions, and the formulations of these detergents are often complex mixtures of a variety of chemicals aside from surfactants, reflecting the diverse demands of the application and the highly competitive consumer market. These detergents may contain the following components:[21]

- surfactants

- foam regulators

- builders

- bleach

- bleach activators

- enzymes

- dyes

- fragrances

- other additives

Fuel additives[edit]

Both carburetors and fuel injector components of internal combustion engines benefit from detergents in the fuels to prevent fouling. Concentrations are about 300 ppm. Typical detergents are long-chain amines and amides such as polyisobuteneamine and polyisobuteneamide/succinimide.[23]

Biological reagent[edit]

Reagent grade detergents are employed for the isolation and purification of integral membrane proteins found in biological cells.[24] Solubilization of cell membrane bilayers requires a detergent that can enter the inner membrane monolayer.[25] Advancements in the purity and sophistication of detergents have facilitated structural and biophysical characterization of important membrane proteins such as ion channels also the disrupt membrane by binding lipopolysaccharide,[26] transporters, signaling receptors, and photosystem II.[27]

See also[edit]

- Cleavable detergent

- Dishwashing liquid

- Dispersant

- Green cleaning

- Hard-surface cleaner

- Laundry detergent

- List of cleaning products

- Triton X-100

References[edit]

- ^ a b IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «detergent». doi:10.1351/goldbook.D01643

- ^ NIIR Board of Consultants Engineers (2013). The Complete Technology Book on Detergents (2nd Revised ed.). p. 1. ISBN 9789381039199 – via Google Books.

- ^ Arno Cahn, ed. (2003). 5th World Conference on Detergents. p. 154. ISBN 9781893997400 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Neugebauer, Judith M. (1990). «Detergents: An overview». Methods in Enzymology. 182: 239–253. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(90)82020-3. PMID 2314239.

- ^ Niir Board (1999). Handbook on Soaps, Detergents & Acid Slurry (3rd Revised ed.). p. 270. ISBN 9788178330938 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mehreteab, Ammanuel (1999). Guy Broze (ed.). Handbook of Detergents, Part A. Taylor & Francis. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9781439833322 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Eduard Smulders, Wolfgang Rybinski, Eric Sung, Wilfried Rähse, Josef Steber, Frederike Wiebel, Anette Nordskog, «Laundry Detergents» in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_315.pub2

- ^ Jürgen Falbe, ed. (2012). Surfactants in Consumer Products. Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9783642715457 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Paul Sosis, Uri Zoller, ed. (2008). Handbook of Detergents, Part F. p. 5. ISBN 9781420014655.

- ^ Aftalion, Fred (2001). A History of the International Chemical Industry. Chemical Heritage Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780941901291.

- ^ Ward, James; Löhr (2020). The Perfection of the Paper Clip. Atria Books. p. 190. ISBN 9781476799872.

- ^ Jakobi, Günter; Löhr, Albrecht (2012). Detergents and Textile Washing. Springer-Verlag. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780895736864.

- ^ «Soaps & Detergent: History (1900s to Now)». American Cleaning Institute. Retrieved on 6 January 2015

- ^ a b c d David O. Whitten; Bessie Emrick Whitten (1 January 1997). Handbook of American Business History: Extractives, manufacturing, and services. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-0-313-25199-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Jürgen Falbe, ed. (2012). Surfactants in Consumer Products. Springer-Verlag. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9783642715457 – via Google Books.

- ^ Urban, David G. (2003). How to Formulate and Compound Industrial Detergents. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9781588988683.

- ^ a b Paul Sosis, Uri Zoller, ed. (2008). Handbook of Detergents, Part F. p. 6. ISBN 9781420014655.

- ^ Paul Sosis, Uri Zoller, ed. (2008). Handbook of Detergents, Part F. p. 497. ISBN 9781420014655.

- ^ Uri Zoller, ed. (2008). Handbook of Detergents, Part E: Applications. Taylor & Francis. p. 331. ISBN 9781574447576.

- ^ David O. Whitten; Bessie Emrick Whitten (1999). Handbook of Detergents, Part A. Taylor & Francis. p. 3. ISBN 9781439833322 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Middelhauve, Birgit (2003). Arno Cahn (ed.). 5th World Conference on Detergents. pp. 64–67. ISBN 9781893997400.

- ^ Long, Heather. «Laundry Detergent History». Love to Know.

- ^ Werner Dabelstein, Arno Reglitzky, Andrea Schütze, Klaus Reders «Automotive Fuels» in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheimdoi:10.1002/14356007.a16_719.pub2

- ^ Koley D, Bard AJ (2010). «Triton X-100 concentration effects on membrane permeability of a single HeLa cell by scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM)». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (39): 16783–7. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716783K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011614107. PMC 2947864. PMID 20837548.

- ^ Lichtenberg D, Ahyayauch H, Goñi FM (2013). «The mechanism of detergent solubilization of lipid bilayers». Biophysical Journal. 105 (2): 289–299. Bibcode:2013BpJ…105..289L. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.007. PMC 3714928. PMID 23870250.

- ^ Doyle, DA; Morais Cabral, J; Pfuetzner, RA; Kuo, A; Gulbis, JM; Cohen, SL; Chait, BT; MacKinnon, R (1998). «The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+conduction and selectivity». Science. 280 (5360): 69–77. Bibcode:1998Sci…280…69D. doi:10.1126/science.280.5360.69. PMID 9525859.

- ^ Umena, Yasufumi; Kawakami, Keisuke; Shen, Jian-Ren; Kamiya, Nobuo (2011). «Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 A» (PDF). Nature. 473 (7345): 55–60. Bibcode:2011Natur.473…55U. doi:10.1038/nature09913. PMID 21499260. S2CID 205224374.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Detergents.

- About.com: How Do Detergents Clean

- Campbell tips for detergents chemistry, surfactants, and history related to laundry washing, destaining methods and soil.

- Formulation of Detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions.[1] There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are more soluble in hard water, because the polar sulfonate (of detergents) is less likely than the polar carboxylate (of soap) to bind to calcium and other ions found in hard water.

Definitions[edit]

Look up detergent in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

The word detergent is derived from the Latin adjective detergens, from the verb detergere, meaning to wipe or polish off. Detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions.[1] However, conventionally, detergent is used to mean synthetic cleaning compounds as opposed to soap (a salt of the natural fatty acid), even though soap is also a detergent in the true sense.[2] In domestic contexts, the term detergent refers to household cleaning products such as laundry detergent or dish detergent, which are in fact complex mixture of different compounds, not all of which are by themselves detergents.

Detergency is the ability to remove unwanted substances termed ‘soils’ from a substrate (e.g clothing).[3]

Structure and properties[edit]

Detergents are a group of compounds with an amphiphilic structure, where each molecule has a hydrophilic (polar) head and a long hydrophobic (non-polar) tail. The hydrophobic portion of these molecules may be straight- or branched-chain hydrocarbons, or it may have a steroid structure. The hydrophilic portion is more varied, they may be ionic or non-ionic, and can range from a simple or a relatively elaborate structure.[4] Detergents are surfactants since they can decrease the surface tension of water. Their dual nature facilitates the mixture of hydrophobic compounds (like oil and grease) with water. Because air is not hydrophilic, detergents are also foaming agents to varying degrees.

Detergent molecules aggregate to form micelles, which makes them soluble in water. The hydrophobic group of the detergent is the main driving force of micelle formation, its aggregation forms the hydrophobic core of the micelles. The micelle can remove grease, protein or soiling particles. The concentration at which micelles start to form is the critical micelle concentration (CMC), and the temperature at which the micelles further aggregate to separate the solution into two phases is the cloud point when the solution becomes cloudy and detergency is optimal.[4]

Detergents work better in an alkaline pH. The properties of detergents are dependent on the molecular structure of the monomer. The ability to foam may be determined by the head group, for example anionic surfactants are high-foaming, while nonionic surfactants may be non-foaming or low-foaming.[5]

Chemical classifications of detergents[edit]

Detergents are classified into four broad groupings, depending on the electrical charge of the surfactants.[6]

Anionic detergents[edit]

Typical anionic detergents are alkylbenzene sulfonates. The alkylbenzene portion of these anions is lipophilic and the sulfonate is hydrophilic. Two varieties have been popularized, those with branched alkyl groups and those with linear alkyl groups. The former were largely phased out in economically advanced societies because they are poorly biodegradable.[7]

Anionic detergents is the most common form of detergents, and an estimated 6 billion kilograms of anionic detergents are produced annually for the domestic markets.

Bile acids, such as deoxycholic acid (DOC), are anionic detergents produced by the liver to aid in digestion and absorption of fats and oils.

Cationic detergents[edit]

Cationic detergents are similar to anionic ones, but quaternary ammonium replaces the hydrophilic anionic sulfonate group. The ammonium sulfate center is positively charged.[7] Cationic surfactants generally have poor detergency.

Non-ionic detergents[edit]

Non-ionic detergents are characterized by their uncharged, hydrophilic headgroups. Typical non-ionic detergents are based on polyoxyethylene or a glycoside. Common examples of the former include Tween, Triton, and the Brij series. These materials are also known as ethoxylates or PEGylates and their metabolites, nonylphenol. Glycosides have a sugar as their uncharged hydrophilic headgroup. Examples include octyl thioglucoside and maltosides. HEGA and MEGA series detergents are similar, possessing a sugar alcohol as headgroup.

Amphoteric detergents[edit]

Amphoteric or zwitterionic detergents have zwitterions within a particular pH range, and possess a net zero charge arising from the presence of equal numbers of +1 and −1 charged chemical groups. Examples include CHAPS.

History[edit]

Soap is known to be have been used as a surfactant for washing clothes since the Sumerian time in 2,500 B.C.[8] In ancient Egypt, soda was used as a wash additive. In the 19th century, synthetic surfactants began to be created, for example from olive oil.[9] Sodium silicate (water glass) was used in soap-making in the United States in the 1860s,[10] and in 1876, Henkel sold a sodium silicate-based product that can be used with soap and marketed as a «universal detergent» (Universalwaschmittel) in Germany. Soda was then mixed with sodium silicate to produce Germany’s first brand name detergent Bleichsoda.[11] In 1907 Henkel also added a bleaching agent sodium perborate to launch the first ‘self-acting’ laundry detergent Persil to eliminate the laborious rubbing of laundry by hand.[12]

During the First World War, there was a shortage of oils and fats needed to make soap. In order find alternatives for soap, synthetic detergents were made in Germany by chemists using raw material derived from coal tar.[13][14][9] These early products, however, did not provide sufficient detergency. In 1928, effective detergent was made through the sulfation of fatty alcohol, but large-scale production was not feasible until low-cost fatty alcohols become available in the early 1930s.[15] The synthetic detergent created was more effective and less likely to form scum than soap in hard water, and can also eliminate acid and alkaline reactions and decompose dirt. Commercial detergent products with fatty alcohol sulphates began to be sold, initially in 1932 in Germany by Henkel.[15] In the United States, detergents were sold in 1933 by Procter & Gamble (Dreft) primarily in areas with hard water.[14] However, sales in the US grew slowly until the introduction of ‘built’ detergents with the addition of effective phosphate builder developed in the early 1940s.[14] The builder improves the performance of the surfactants by softening the water through the chelation of calcium and magnesium ions, helping to maintain an alkaline pH, as well as dispersing and keeping the soiling particles in solution.[16] The development of the petrochemical industry after the Second World War also yielded material for the production of a range of synthetic surfactants, and alkylbenzene sulfonates became the most important detergent surfactants used.[17] By the 1950s, laundry detergents had become widespread, and largely replaced soap for cleaning clothes in developed countries.[15]

Over the years, many types of detergents have been developed for a variety of purposes, for example, low-sudsing detergents for use in front-loading washing machines, heavy-duty detergents effective in removing grease and dirt, all-purpose detergents and specialty detergents.[14][18] They become incorporated in various products outside of laundry use, for example in dishwasher detergents, shampoo, toothpaste, industrial cleaners, and in lubricants and fuels to reduce or prevent the formation of sludge or deposits.[19] The formulation of detergent products may include bleach, fragrances, dyes and other additives. The use of phosphates in detergent, however, led to concerns over nutrient pollution and demand for changes to the formulation of the detergents.[20] Concerns were also raised over the use of surfactants such as branched alkylbenzene sulfonate (tetrapropylenebenzene sulfonate) that lingers in the environment, which led to their replacement by surfactants that are more biodegradable, such as linear alkylbenzene sulfonate.[15][17] Developments over the years have included the use of enzymes, substitutes for phosphates such as zeolite A and NTA, TAED as bleach activator, sugar-based surfactants which are biodegradable and milder to skin, and other green friendly products, as well as changes to the form of delivery such as tablets, gels and pods.[21][22]

Major applications of detergents[edit]

Household cleaning[edit]

One of the largest applications of detergents is for household and shop cleaning including dish washing and washing laundry. These detergents are commonly available as powders or concentrated solutions, and the formulations of these detergents are often complex mixtures of a variety of chemicals aside from surfactants, reflecting the diverse demands of the application and the highly competitive consumer market. These detergents may contain the following components:[21]

- surfactants

- foam regulators

- builders

- bleach

- bleach activators

- enzymes

- dyes

- fragrances

- other additives

Fuel additives[edit]

Both carburetors and fuel injector components of internal combustion engines benefit from detergents in the fuels to prevent fouling. Concentrations are about 300 ppm. Typical detergents are long-chain amines and amides such as polyisobuteneamine and polyisobuteneamide/succinimide.[23]

Biological reagent[edit]

Reagent grade detergents are employed for the isolation and purification of integral membrane proteins found in biological cells.[24] Solubilization of cell membrane bilayers requires a detergent that can enter the inner membrane monolayer.[25] Advancements in the purity and sophistication of detergents have facilitated structural and biophysical characterization of important membrane proteins such as ion channels also the disrupt membrane by binding lipopolysaccharide,[26] transporters, signaling receptors, and photosystem II.[27]

See also[edit]

- Cleavable detergent

- Dishwashing liquid

- Dispersant

- Green cleaning

- Hard-surface cleaner

- Laundry detergent

- List of cleaning products

- Triton X-100

References[edit]

- ^ a b IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «detergent». doi:10.1351/goldbook.D01643

- ^ NIIR Board of Consultants Engineers (2013). The Complete Technology Book on Detergents (2nd Revised ed.). p. 1. ISBN 9789381039199 – via Google Books.

- ^ Arno Cahn, ed. (2003). 5th World Conference on Detergents. p. 154. ISBN 9781893997400 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Neugebauer, Judith M. (1990). «Detergents: An overview». Methods in Enzymology. 182: 239–253. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(90)82020-3. PMID 2314239.

- ^ Niir Board (1999). Handbook on Soaps, Detergents & Acid Slurry (3rd Revised ed.). p. 270. ISBN 9788178330938 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mehreteab, Ammanuel (1999). Guy Broze (ed.). Handbook of Detergents, Part A. Taylor & Francis. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9781439833322 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Eduard Smulders, Wolfgang Rybinski, Eric Sung, Wilfried Rähse, Josef Steber, Frederike Wiebel, Anette Nordskog, «Laundry Detergents» in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_315.pub2

- ^ Jürgen Falbe, ed. (2012). Surfactants in Consumer Products. Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9783642715457 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Paul Sosis, Uri Zoller, ed. (2008). Handbook of Detergents, Part F. p. 5. ISBN 9781420014655.

- ^ Aftalion, Fred (2001). A History of the International Chemical Industry. Chemical Heritage Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780941901291.

- ^ Ward, James; Löhr (2020). The Perfection of the Paper Clip. Atria Books. p. 190. ISBN 9781476799872.

- ^ Jakobi, Günter; Löhr, Albrecht (2012). Detergents and Textile Washing. Springer-Verlag. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780895736864.

- ^ «Soaps & Detergent: History (1900s to Now)». American Cleaning Institute. Retrieved on 6 January 2015

- ^ a b c d David O. Whitten; Bessie Emrick Whitten (1 January 1997). Handbook of American Business History: Extractives, manufacturing, and services. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-0-313-25199-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Jürgen Falbe, ed. (2012). Surfactants in Consumer Products. Springer-Verlag. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9783642715457 – via Google Books.

- ^ Urban, David G. (2003). How to Formulate and Compound Industrial Detergents. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9781588988683.

- ^ a b Paul Sosis, Uri Zoller, ed. (2008). Handbook of Detergents, Part F. p. 6. ISBN 9781420014655.

- ^ Paul Sosis, Uri Zoller, ed. (2008). Handbook of Detergents, Part F. p. 497. ISBN 9781420014655.

- ^ Uri Zoller, ed. (2008). Handbook of Detergents, Part E: Applications. Taylor & Francis. p. 331. ISBN 9781574447576.

- ^ David O. Whitten; Bessie Emrick Whitten (1999). Handbook of Detergents, Part A. Taylor & Francis. p. 3. ISBN 9781439833322 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Middelhauve, Birgit (2003). Arno Cahn (ed.). 5th World Conference on Detergents. pp. 64–67. ISBN 9781893997400.

- ^ Long, Heather. «Laundry Detergent History». Love to Know.

- ^ Werner Dabelstein, Arno Reglitzky, Andrea Schütze, Klaus Reders «Automotive Fuels» in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheimdoi:10.1002/14356007.a16_719.pub2

- ^ Koley D, Bard AJ (2010). «Triton X-100 concentration effects on membrane permeability of a single HeLa cell by scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM)». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (39): 16783–7. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716783K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011614107. PMC 2947864. PMID 20837548.

- ^ Lichtenberg D, Ahyayauch H, Goñi FM (2013). «The mechanism of detergent solubilization of lipid bilayers». Biophysical Journal. 105 (2): 289–299. Bibcode:2013BpJ…105..289L. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.007. PMC 3714928. PMID 23870250.

- ^ Doyle, DA; Morais Cabral, J; Pfuetzner, RA; Kuo, A; Gulbis, JM; Cohen, SL; Chait, BT; MacKinnon, R (1998). «The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+conduction and selectivity». Science. 280 (5360): 69–77. Bibcode:1998Sci…280…69D. doi:10.1126/science.280.5360.69. PMID 9525859.

- ^ Umena, Yasufumi; Kawakami, Keisuke; Shen, Jian-Ren; Kamiya, Nobuo (2011). «Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 A» (PDF). Nature. 473 (7345): 55–60. Bibcode:2011Natur.473…55U. doi:10.1038/nature09913. PMID 21499260. S2CID 205224374.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Detergents.

- About.com: How Do Detergents Clean

- Campbell tips for detergents chemistry, surfactants, and history related to laundry washing, destaining methods and soil.

- Formulation of Detergent