Откройте возможности нейронного машинного перевода PROMT

PROMT.One — это облачное приложение – бесплатный онлайн-переводчик

для перевода с языка на язык на основе нейронных сетей (Neural Machine Translation),

словарь с транскрипцией, разговорники и многое другое. Наслаждайтесь правильным и точным переводом на английский, немецкий и еще 20+ языков.

Смотрите перевод слов и устойчивых выражений, транскрипцию и произношение в онлайн cловаре. Словари PROMT для

английского,

немецкого,

французского,

русского,

испанского,

итальянского и

португальского языков включают миллионы слов и словосочетаний, самую современную разговорную

лексику, которая постоянно отслеживается и пополняется нашими лингвистами.

Изучайте формы английских глаголов,

немецких глаголов,

испанских глаголов,

французских глаголов,

португальских глаголов,

итальянских глаголов,

русских глаголов

и падежные формы существительных и прилагательных в разделе

Спряжение и

склонение

.

Учите употребление слов и выражений в разных Контекстах.

Миллионы реальных примеров на

английском,

немецком,

испанском,

французском

помогут вам в изучении иностранных языков и подготовке домашних заданий.

Переводите в любом месте и в любое время с помощью бесплатного мобильного переводчика PROMT.One для iOS и

Android. Попробуйте голосовой и фотоперевод.

Установите языковые пакеты для офлайн-перевода на мобильных устройствах и универсальный плагин PROMT АГЕНТ для Windows

с подпиской PREMIUM.

-

1

München

Allgemeines Lexikon > München

-

2

München

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > München

-

3

München

Deutsch-Polnisch Wörterbuch neuer > München

-

4

München

БНРС > München

-

5

München

Deutsch-russische wörterbuch der kunst > München

-

6

München

Универсальный немецко-русский словарь > München

-

7

München

n

Мюнхен

город в Германии на р. Изар, адм. центр земли Бавария; 1,24 млн. жителей; основан в 1158; машиностроение, оптическая, электротехническая, полиграфическая, текстильная промышленность; многочисленные памятники архитектуры, музеи, театры; университет, академия искусств, высшая школа музыки и др. вузы

Altes Residenztheater, Asamkirche, Bayern, Bayerisches Armeemuseum, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Bayerische Staatsoper, Deutsches Theatermuseum, Frauenkirche, Gasteig, Glyptothek, Isar, Pinakothek, Nymphenburg

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der regionalen Studien > München

-

8

München

Универсальный немецко-русский словарь > München

-

9

München

Современный немецко-русский словарь общей лексики > München

-

10

München Mitt.

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der Astronomie > München Mitt.

-

11

München Veröff.

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der Astronomie > München Veröff.

-

12

München Mitt.

Универсальный немецко-русский словарь > München Mitt.

-

13

München Veröff.

Универсальный немецко-русский словарь > München Veröff.

-

14

Olympische Sommerspiele in München

Летние Олимпийские игры в Мюнхене

XX — состоялись с 26.8. по 11.9.1972

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der regionalen Studien > Olympische Sommerspiele in München

-

15

Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film München

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film München

-

16

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

f

Университет Людвига Максимилиана г. Мюнхен

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

-

17

Carl Prandtl GmbH München

Акционерное общество с ограниченной ответственностью «Карл Прандтл», г. Мюнхен

Das Deutsch-Russische Wörterbuch des Biers > Carl Prandtl GmbH München

-

18

Interbrau-Drinktec 97 in München

Мюнхенская ярмарка техники и технологии производства напитков Интербрау-97

Das Deutsch-Russische Wörterbuch des Biers > Interbrau-Drinktec 97 in München

-

19

Mitteilungen der Sternwarte München

астр.Сообщения Мюнхенской (астрономической) обсерватории (ФРГ)

астр.

Сообщения Мюнхенской (астрономической) обсерватории

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der Astronomie > Mitteilungen der Sternwarte München

-

20

Sternwarte München

астр.Мюнхенская (астрономическая) обсерватория (ФРГ)

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der Astronomie > Sternwarte München

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

См. также в других словарях:

-

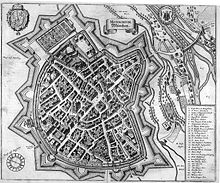

München — (hierzu der Stadtplan, mit Registerblatt, Tafel »Münchener Bauten I III« und Karte »Umgebung von München«), die Haupt und Residenzstadt des Königreichs Bayern, liegt zu beiden Seiten der Isar, wo die steilen Ufer des Flusses auseinanderrücken und … Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon

-

München 21 — war ein Projekt im Rahmen der Bahnhof 21 Planungen der Deutschen Bahn AG mit dem Ziel, den Kopfbahnhof des Münchner Hauptbahnhofes durch einen Durchgangsbahnhof im Untergrund zu ersetzen. Durch diese Maßnahme sollte eine Zeitersparnis für den… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

München.tv — München TV (Eigenschreibweise münchen.tv) ist ein regionaler Fernsehsender aus München. Der Sender wird von der München Live TV Fernsehen GmbH Co KG produziert. Diese war entstanden, nachdem die Bayerische Landeszentrale für neue Medien dem… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

München 7 — ist eine 13 teilige Fernseh Polizistenserie von Franz Xaver Bogner, die für den Bayerischen Rundfunk produziert wurde. Die Fernsehserie spielt in München und handelt vom Alltag des erfundenen Polizeireviers München 7. Die neun ersten Folgen… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

München — München, 1) Landgericht rechts der Isar im baierischen Regierungsbezirk Oberbaiern mit 10,240 Einwohnern; 2) Landgericht links der Isar in demselben Regierungsbezirk mit 14,020 Ew; 3) Bezirksgericht rechts der Isar, umfaßt die Bestandtheile der… … Pierer’s Universal-Lexikon

-

München — München, in einer Ebene am linken Ufer des Isarflusses gelegen, die Haupt und Residenzstadt des Königreichs Baiern, mit 90,000 Ew., war bereits im 11. Jahrhunderte ein nicht unbedeutender Ort, und hat sich namentlich in neuerer Zeit sehr… … Damen Conversations Lexikon

-

München 7 — Country of origin Germany München 7 is a German television series. See also List of German television series External links München 7 at the Internet Movie Database … Wikipedia

-

München — [Wichtig (Rating 3200 5600)] Bsp.: • Der Flug nach München geht jetzt ab … Deutsch Wörterbuch

-

München — München, verschneiden, S. 2 Mönch … Grammatisch-kritisches Wörterbuch der Hochdeutschen Mundart

-

München — München, Haupt und Residenzstadt des Königreichs Bayern und Hauptstadt des Kreises Oberbayern, Sitz eines Erzbischofs, an der Isar, 1589 Par. Fuß über dem Meere auf einer einförmigen Ebene gelegen, hat mit seinen 5 Vorstädten über 116000 E.,… … Herders Conversations-Lexikon

-

München — (izg. Mìnhen) m glavni grad Bavarske (Njemačka) … Veliki rječnik hrvatskoga jezika

|

Munich München (German) |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

From top, left to right: |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

|

Location of Munich |

|

|

Munich Munich |

|

| Coordinates: 48°08′15″N 11°34′30″E / 48.13750°N 11.57500°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Bavaria |

| Admin. region | Upper Bavaria |

| District | Urban district |

| First mentioned | 1158 |

| Subdivisions |

25 boroughs

|

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2020–26) | Dieter Reiter[1] (SPD) |

| • Governing parties | Greens / SPD |

| Area | |

| • City | 310.71 km2 (119.97 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 520 m (1,710 ft) |

| Population

(2021-12-31)[3] |

|

| • City | 1,487,708 |

| • Density | 4,800/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,606,021 |

| • Metro | 5,991,144[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes |

80331–81929 |

| Dialling codes | 089 |

| Vehicle registration | M |

| Website | stadt.muenchen.de |

Munich ( MEW-nik; German: München [ˈmʏnçn̩] (listen); Bavarian: Minga [ˈmɪŋ(ː)ɐ] (

listen)) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020,[4] it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Hamburg, and thus the largest which does not constitute its own state, as well as the 11th-largest city in the European Union. The city’s metropolitan region is home to 6 million people.[5] Straddling the banks of the River Isar (a tributary of the Danube) north of the Bavarian Alps, Munich is the seat of the Bavarian administrative region of Upper Bavaria, while being the most densely populated municipality in Germany (4,500 people per km2). Munich is the second-largest city in the Bavarian dialect area, after the Austrian capital of Vienna.

The city was first mentioned in 1158. Catholic Munich strongly resisted the Reformation and was a political point of divergence during the resulting Thirty Years’ War, but remained physically untouched despite an occupation by the Protestant Swedes.[6] Once Bavaria was established as a sovereign kingdom in 1806, Munich became a major European centre of arts, architecture, culture and science. In 1918, during the German Revolution, the ruling house of Wittelsbach, which had governed Bavaria since 1180, was forced to abdicate in Munich and a short-lived socialist republic was declared. In the 1920s, Munich became home to several political factions, among them the NSDAP. After the Nazis’ rise to power, Munich was declared their «Capital of the Movement». The city was heavily bombed during World War II, but has restored most of its traditional cityscape. After the end of postwar American occupation in 1949, there was a great increase in population and economic power during the years of Wirtschaftswunder, or «economic miracle». The city hosted the 1972 Summer Olympics and was one of the host cities of the 1974 and 2006 FIFA World Cups.

Today, Munich is a global centre of art, science, technology, finance, publishing, culture, innovation, education, business, and tourism and enjoys a very high standard and quality of living, reaching first in Germany and third worldwide according to the 2018 Mercer survey,[7] and being rated the world’s most liveable city by the Monocle’s Quality of Life Survey 2018.[8] Munich is consistently ranked as one of the most expensive cities in Germany in terms of real estate prices and rental costs.[9][10] According to the Globalization and World Rankings Research Institute, Munich is considered an alpha-world city, as of 2015.[11] It is one of the most prosperous[12] and fastest growing[13] cities in Germany. The city is home to more than 530,000 people of foreign background, making up 37.7% of its population.[14]

Munich’s economy is based on high tech, automobiles, the service sector and creative industries, as well as IT, biotechnology, engineering and electronics among many other sectors. It has one of the strongest economies of any German city and the lowest unemployment rate of all cities in Germany with more than 1 million inhabitants. Munich is also one of the most attractive business locations in Germany. The city houses many multinational companies, such as BMW, Siemens, MAN, Allianz and MunichRE. In addition, Munich is home to two research universities, a multitude of scientific institutions, and world-renowned technology and science museums like the Deutsches Museum and BMW Museum.[15] Munich’s numerous architectural and cultural attractions, sports events, exhibitions and its annual Oktoberfest, the world’s largest Volksfest, attract considerable tourism.[16]

History[edit]

«Solang der alte Peter», the city anthem of Munich

Etymology[edit]

The name of the city is usually interpreted as deriving from the Old/Middle High German form Munichen, meaning «by the monks». A monk is also depicted on the city’s coat of arms.

The town is first mentioned as forum apud Munichen in the Augsburg arbitration [de] of 14 June 1158 by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I.[17][18]

The name in modern German is München, but this has been variously translated in different languages: in English, French, Spanish and various other languages as «Munich», in Italian as «Monaco di Baviera», in Portuguese as «Munique».[19]

Prehistory[edit]

Archeological finds in Munich, such as in Freiham/Aubing, indicate early settlements and graves dating back to the Bronze Age (7th–6th century BC).[20][21]

Evidence of Celtic settlements from the Iron Age have been discovered in areas around Perlach.[22]

Roman period[edit]

The ancient Roman road Via Julia, which connected Augsburg and Salzburg, crossed over the Isar River south of modern-day Munich, at the towns of Baierbrunn and Gauting.[23]

A Roman settlement north-east of downtown Munich was excavated in the neighborhood of Denning/Bogenhausen.[24]

Post-Roman settlements[edit]

In the 6th Century and beyond, various ethnic groups, such as the Baiuvarii, populated the area around what is now modern Munich, such as in Johanneskirchen, Feldmoching, Bogenhausen and Pasing.[25][26]

The first known Christian church was built ca. 815 in Fröttmanning.[27]

Origin of medieval town[edit]

Munich in the 16th century

The origin of the modern city of Munich is the result of a power struggle between a military warlord and an influential Catholic bishop.

Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Duke of Bavaria (d. 1195) was one of the most powerful German princes of his time. He ruled over vast territories in the German Holy Roman Empire from the North and Baltic Sea to the Alps. Henry wanted to expand his power in Bavaria by gaining control of the lucrative salt trade, which the Catholic Church in Freising had under its control.

Bishop Otto von Freising (d. 1158) was a scholar, historian and bishop of a large section of Bavaria that was part of his diocese of Freising.

Years earlier (the exact time is unclear, but may have been in the early 10th century), Benedictine monks helped build a toll bridge and a customs house over the Isar River (most likely in the modern town of Oberföhring) to control the salt trade between Augsburg and Salzburg (which had existed since Roman times).

Henry wanted to control the toll bridge and its income for himself, so he destroyed the bridge and customs house in 1156. He then built a new toll bridge, customs house and a coin market closer to his home somewhat upstream (at a settlement around the area of modern oldtown Munich: Marienplatz, Marienhof and the St. Peter’s Church). This new toll bridge most likely crossed the Isar where the Museuminsel and the modern Ludwigsbrücke is now located.[28]

Bishop Otto protested to his nephew, Emperor Frederick Barbarosa (d. 1190). However, on 14 June 1158, in Augsburg, the conflict was settled in favor of Duke Henry. The Augsburg Arbitration mentions the name of the location in dispute as forum apud Munichen. Although Bishop Otto had lost his bridge, the arbiters ordered Duke Henry to pay a third of his income to the Bishop in Freising as compensation.[29][30][31]

14 June 1158, is considered the official ‘founding day’ of the city of Munich, not the date when it was first settled.

Archaeological excavations at Marienhof Square (near Marienplatz) in advance of the expansion of the S-Bahn (subway) in 2012 discovered shards of vessels from the 11th century, which prove again that the settlement of Munich must be older than the Augsburg Arbitration of 1158.[32][33] The old St. Peter’s Church near Marienplatz is also believed to predate the founding date of the town.[34]

In 1175, Munich received city status and fortification. In 1180, after Henry the Lion’s fall from grace with Emperor Frederick Barbarosa, including his trial and exile, Otto I Wittelsbach became Duke of Bavaria, and Munich was handed to the Bishop of Freising. In 1240, Munich was transferred to Otto II Wittelsbach and in 1255, when the Duchy of Bavaria was split in two, Munich became the ducal residence of Upper Bavaria.

Duke Louis IV, a native of Munich, was elected German king in 1314 and crowned as Holy Roman Emperor in 1328. He strengthened the city’s position by granting it the salt monopoly, thus assuring it of additional income.

On 13 February 1327, a large fire broke out in Munich that lasted two days and destroyed about a third of the town.[35]

In 1349, the Black Death ravaged Munich and Bavaria.[36]

In the 15th century, Munich underwent a revival of Gothic arts: the Old Town Hall was enlarged, and Munich’s largest Gothic church – the Frauenkirche – now a cathedral, was constructed in only 20 years, starting in 1468.

Capital of reunited Bavaria[edit]

Banners with the colours of Munich (left) and Bavaria (right) with the Frauenkirche in the background

When Bavaria was reunited in 1506 after a brief war against the Duchy of Landshut, Munich became its capital. The arts and politics became increasingly influenced by the court (see Orlando di Lasso and Heinrich Schütz). During the 16th century, Munich was a centre of the German counter reformation, and also of renaissance arts. Duke Wilhelm V commissioned the Jesuit Michaelskirche, which became a centre for the counter-reformation, and also installed the Hofbräuhaus for brewing brown beer in 1589. The Catholic League was founded in Munich in 1609.

In 1623, during the Thirty Years’ War, Munich became an electoral residence when Maximilian I, Duke of Bavaria was invested with the electoral dignity, but in 1632 the city was occupied by Gustav II Adolph of Sweden. When the bubonic plague broke out in 1634 and 1635, about one-third of the population died. Under the regency of the Bavarian electors, Munich was an important centre of Baroque life, but also had to suffer under Habsburg occupations in 1704 and 1742.

After making an alliance with Napoleonic France, the city became the capital of the new Kingdom of Bavaria in 1806 with Elector Maximillian Joseph becoming its first King. The state parliament (the Landtag) and the new archdiocese of Munich and Freising were also located in the city.

During the early to mid-19th century, the old fortified city walls of Munich were largely demolished due to population expansion.[37]

Munich’s annual Beer Festival, Oktoberfest, has its origins from a royal wedding in October 1810. The fields are now part of the ‘Theresienwiese’ near downtown.

In 1826, Landshut University was moved to Munich. Many of the city’s finest buildings belong to this period and were built under the first three Bavarian kings. Especially Ludwig I rendered outstanding services to Munich’s status as a centre of the arts, attracting numerous artists and enhancing the city’s architectural substance with grand boulevards and buildings.[38]

The first Munich railway station was built in 1839, with a line going to Augsburg in the west. By 1849 a newer Munich Central Train Station (München Hauptbahnhof) was completed, with a line going to Landshut and Regensburg in the north.[39][40]

By the time Ludwig II became king in 1864, he remained mostly aloof from his capital and focused more on his fanciful castles in the Bavarian countryside, which is why he is known the world over as the ‘fairytale king’. Nevertheless, his patronage of Richard Wagner secured his posthumous reputation, as do his castles, which still generate significant tourist income for Bavaria. Later, Prince Regent Luitpold’s years as regent were marked by tremendous artistic and cultural activity in Munich, enhancing its status as a cultural force of global importance (see Franz von Stuck and Der Blaue Reiter).

World War I to World War II[edit]

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, life in Munich became very difficult, as the Allied blockade of Germany led to food and fuel shortages. During French air raids in 1916, three bombs fell on Munich.

In March 1916, three separate aircraft-engine and automobile companies joined to form ‘Bayerische Motoren Werke’ (BMW) in Munich.[41]

After World War I, the city was at the centre of substantial political unrest. In November 1918, on the eve of the German revolution, Ludwig III and his family fled the city. After the murder of the first republican premier of Bavaria Kurt Eisner in February 1919 by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley, the Bavarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed. When Communists took power, Lenin, who had lived in Munich some years before, sent a congratulatory telegram, but the Soviet Republic was ended on 3 May 1919 by the Freikorps. While the republican government had been restored, Munich became a hotbed of extremist politics, among which Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists soon rose to prominence.

Bombing damage to the Altstadt. Note the roofless and pockmarked Altes Rathaus looking up the Tal. The roofless Heilig-Geist-Kirche is on the right of the photo. Its spire, without the copper top, is behind the church. The Talbruck gate tower is missing completely.

Munich’s first film studio (Bavaria Film) was founded in 1919.[42]

In 1923, Adolf Hitler and his supporters, who were concentrated in Munich, staged the Beer Hall Putsch, an attempt to overthrow the Weimar Republic and seize power. The revolt failed, resulting in Hitler’s arrest and the temporary crippling of the Nazi Party (NSDAP). The city again became important to the Nazis when they took power in Germany in 1933. The party created its first concentration camp at Dachau, 16 km (9.9 mi) north-west of the city. Because of its importance to the rise of National Socialism, Munich was referred to as the Hauptstadt der Bewegung («Capital of the Movement»).[43] The NSDAP headquarters were in Munich and many Führerbauten («Führer buildings») were built around the Königsplatz, some of which still survive.

In March 1924, Munich broadcast its first radio program. The station became ‘Bayerischer Rundfunk’ in 1931.[44]

The city was the site where the 1938 Munich Agreement signed between Britain and France with Germany as part of the Franco-British policy of appeasement. The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain assented to the German annexation of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland region in the hopes of satisfying Hitler’s territorial expansion.[45]

The first airport in Munich was completed in October 1939, in the area of Riem. The airport would remain there until it was moved closer to Freising in 1992.[46]

On November 8, 1939, shortly after the Second World War had begun, a bomb was planted in the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich in an attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler during a political party speech. Hitler, however, had left the building minutes before the bomb went off. On its site today stands the GEMA Building, the Gasteig Cultural Centre and the Munich City Hilton Hotel.[47]

Munich was the base of the White Rose, a student resistance movement from June 1942 to February 1943. The core members were arrested and executed following a distribution of leaflets in Munich University by Hans and Sophie Scholl.

The city was heavily damaged by Allied bombing during World War II, with 71 air raids over five years. US troops liberated Munich on April 30, 1945.[48]

Postwar[edit]

After US occupation in 1945, Munich was completely rebuilt following a meticulous plan, which preserved its pre-war street grid, bar a few exceptions owing to then modern traffic concepts. In 1957, Munich’s population surpassed one million. The city continued to play a highly significant role in the German economy, politics and culture, giving rise to its nickname Heimliche Hauptstadt («secret capital») in the decades after World War II.[49]

In Munich, Bayerischer Rundfunk began its first television broadcast in 1954.[50]

Since 1963, Munich has been the host city for annual conferences on international security policy.

Munich also became known on the political level due to the strong influence of Bavarian politician Franz Josef Strauss from the 1960s to the 1980s. The Munich Airport (built in 1992) was named in his honor.[51]

Munich was the site of the 1972 Summer Olympics, during which 11 Israeli athletes were murdered by Palestinian terrorists in the Munich massacre, when gunmen from the Palestinian «Black September» group took hostage members of the Israeli Olympic team. [52] Mass murders also occurred in Munich in 1980 and 2016.

Munich also hosted the FIFA World Cup finals in 1974.

Munich is also home of the famous Nockherberg Strong Beer Festival during the Lenten fasting period (usually in March). Its origins go back to the 17th/18th century, but has become popular when the festivities were first televised in the 1980s. The fest includes comical speeches and a mini-musical in which numerous German politicians are parodied by look-alike actors.[53]

Munich was one of the host cities for the 2006 FIFA World Cup.

Munich was one of the host cities for the UEFA European 2020 football championship, (which was delayed for a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany).

Geography[edit]

Satellite photo by ESA Sentinel-2

Topography[edit]

Munich lies on the elevated plains of Upper Bavaria, about 50 km (31 mi) north of the northern edge of the Alps, at an altitude of about 520 m (1,706 ft) ASL. The local rivers are the Isar and the Würm.

Munich is situated in the Northern Alpine Foreland. The northern part of this sandy plateau includes a highly fertile flint area which is no longer affected by the folding processes found in the Alps, while the southern part is covered with morainic hills. Between these are fields of fluvio-glacial out-wash, such as around Munich. Wherever these deposits get thinner, the ground water can permeate the gravel surface and flood the area, leading to marshes as in the north of Munich.

Climate[edit]

By Köppen classification templates and updated data the climate is oceanic (Cfb), independent of the isotherm but with some humid continental (Dfb) features like warm to hot summers and cold winters, but without permanent snow cover.[54][55] The proximity to the Alps brings higher volumes of rainfall and consequently greater susceptibility to flood problems. Studies of adaptation to climate change and extreme events are carried out, one of them is the Isar Plan of the EU Adaptation Climate.[56]

The city centre lies between both climates, while the airport of Munich has a humid continental climate. The warmest month, on average, is July. The coolest is January.

Showers and thunderstorms bring the highest average monthly precipitation in late spring and throughout the summer. The most precipitation occurs in July, on average. Winter tends to have less precipitation, the least in February.

The higher elevation and proximity to the Alps cause the city to have more rain and snow than many other parts of Germany. The Alps affect the city’s climate in other ways too; for example, the warm downhill wind from the Alps (föhn wind), which can raise temperatures sharply within a few hours even in the winter.

Being at the centre of Europe, Munich is subject to many climatic influences, so that weather conditions there are more variable than in other European cities, especially those further west and south of the Alps.

At Munich’s official weather stations, the highest and lowest temperatures ever measured are 37.5 °C (100 °F), on 27 July 1983 in Trudering-Riem, and −31.6 °C (−24.9 °F), on 12 February 1929 in Botanic Garden of the city.[57][58]

| Climate data for Munich (Dreimühlenviertel), elevation: 515 m and 535 m, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1954–present[a] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.8 (89.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

4.4 (39.9) |

1.3 (34.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

1.6 (34.9) |

4.9 (40.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.2 (−8.0) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

−16.0 (3.2) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

1.0 (33.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−20.7 (−5.3) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 48 (1.9) |

46 (1.8) |

65 (2.6) |

65 (2.6) |

101 (4.0) |

118 (4.6) |

122 (4.8) |

115 (4.5) |

75 (3.0) |

65 (2.6) |

61 (2.4) |

65 (2.6) |

944 (37.2) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 79 | 96 | 133 | 170 | 209 | 210 | 238 | 220 | 163 | 125 | 75 | 59 | 1,777 |

| Source 1: DWD[60] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SKlima.de[61] |

Climate change[edit]

In Munich, the general trend of global warming with a rise of medium yearly temperatures of about 1 °C in Germany over the last 120 years can be observed as well. In November 2016 the city council concluded officially that a further rise in medium temperature, a higher number of heat extremes, a rise in the number of hot days and nights with temperatures higher than 20 °C (tropical nights), a change in precipitation patterns, as well as a rise in the number of local instances of heavy rain, is to be expected as part of the ongoing climate change.[62] The city administration decided to support a joint study from its own Referat für Gesundheit und Umwelt (department for health and environmental issues) and the German Meteorological Service that will gather data on local weather. The data is supposed to be used to create a plan for action for adapting the city to better deal with climate change as well as an integrated action program for climate protection in Munich. With the help of those programs issues regarding spatial planning and settlement density, the development of buildings and green spaces as well as plans for functioning ventilation in a cityscape can be monitored and managed.[63]

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 13,447 | — |

| 1600 | 21,943 | +63.2% |

| 1750 | 32,000 | +45.8% |

| 1880 | 230,023 | +618.8% |

| 1890 | 349,024 | +51.7% |

| 1900 | 499,932 | +43.2% |

| 1910 | 596,467 | +19.3% |

| 1920 | 666,000 | +11.7% |

| 1930 | 728,900 | +9.4% |

| 1940 | 834,500 | +14.5% |

| 1950 | 823,892 | −1.3% |

| 1955 | 929,808 | +12.9% |

| 1960 | 1,055,457 | +13.5% |

| 1965 | 1,214,603 | +15.1% |

| 1970 | 1,311,978 | +8.0% |

| 1980 | 1,298,941 | −1.0% |

| 1990 | 1,229,026 | −5.4% |

| 2000 | 1,210,223 | −1.5% |

| 2005 | 1,259,584 | +4.1% |

| 2010 | 1,353,186 | +7.4% |

| 2011 | 1,364,920 | +0.9% |

| 2012 | 1,388,308 | +1.7% |

| 2013 | 1,402,455 | +1.0% |

| 2015 | 1,450,381 | +3.4% |

| 2018 | 1,471,508 | +1.5% |

| 2020 | 1,488,202 | +1.1% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. |

From only 24,000 inhabitants in 1700, the city population doubled about every 30 years. It was 100,000 in 1852, 250,000 in 1883 and 500,000 in 1901. Since then, Munich has become Germany’s third-largest city. In 1933, 840,901 inhabitants were counted, and in 1957 over 1 million.

Immigration[edit]

In July 2017, Munich had 1.42 million inhabitants; 421,832 foreign nationals resided in the city as of 31 December 2017 with 50.7% of these residents being citizens of EU member states, and 25.2% citizens in European states not in the EU (including Russia and Turkey).[64] The largest groups of foreign nationals were Turks (39,204), Croats (33,177), Italians (27,340), Greeks (27,117), Poles (27,945), Austrians (21,944), and Romanians (18,085).

| Foreign residents by Citizenship by the end of 2020 [65] | |

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| 39,145 | |

| 37,207 | |

| 28,496 | |

| 26,613 | |

| 21,559 | |

| 20,741 | |

| 18,845 | |

| 18,639 | |

| 14,283 | |

| 13,636 | |

| 11,854 | |

| 11,228 | |

| 11,093 | |

| 10,650 | |

| 9,526 | |

| 9,414 | |

| 9,240 | |

| 8,269 | |

| 7,446 | |

| 7,133 | |

| 6,705 | |

| 4,899 | |

| 4,614 | |

| 4,297 |

Religion[edit]

About 45% of Munich’s residents are not affiliated with any religious group; this ratio represents the fastest growing segment of the population. As in the rest of Germany, the Catholic and Protestant churches have experienced a continuous decline in membership. As of 31 December 2017, 31.8% of the city’s inhabitants were Catholic, 11.4% Protestant, 0.3% Jewish,[66] and 3.6% were members of an Orthodox Church (Eastern Orthodox or Oriental Orthodox).[67] About 1% adhere to other Christian denominations. There is also a small Old Catholic parish and an English-speaking parish of the Episcopal Church in the city. According to Munich Statistical Office, in 2013 about 8.6% of Munich’s population was Muslim.[68]

Government and politics[edit]

As the capital of Bavaria, Munich is an important political centre for both the state and country as a whole. It is the seat of the Landtag of Bavaria, the State Chancellery, and all state departments. Several national and international authorities are located in Munich, including the Federal Finance Court of Germany, the German Patent Office and the European Patent Office.

Mayor[edit]

The current mayor of Munich is Dieter Reiter of the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SPD), who was elected in 2014 and re-elected in 2020. Munich has a much stronger left-wing tradition than the rest of the state, which has been dominated by the conservative Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) on a federal, state, and local level since the establishment of the Federal Republic in 1949. Munich, by contrast, has been governed by the SPD for all but six years since 1948. As of the 2020 local elections, green and centre-left parties also hold a majority in the city council (Stadtrat).

The most recent mayoral election was held on 15 March 2020, with a runoff held on 29 March, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Dieter Reiter | Social Democratic Party | 259,928 | 47.9 | 401,856 | 71.7 | |

| Kristina Frank | Christian Social Union | 115,795 | 21.3 | 158,773 | 28.3 | |

| Katrin Habenschaden | Alliance 90/The Greens | 112,121 | 20.7 | |||

| Wolfgang Wiehle | Alternative for Germany | 14,988 | 2.8 | |||

| Tobias Ruff | Ecological Democratic Party | 8,464 | 1.6 | |||

| Jörg Hoffmann | Free Democratic Party | 8,201 | 1.5 | |||

| Thomas Lechner | The Left | 7,232 | 1.3 | |||

| Hans-Peter Mehling | Free Voters of Bavaria | 5,003 | 0.9 | |||

| Moritz Weixler | Die PARTEI | 3,508 | 0.6 | |||

| Dirk Höpner | Munich List | 1,966 | 0.4 | |||

| Richard Progl | Bavaria Party | 1,958 | 0.4 | |||

| Ender Beyhan-Bilgin | FAIR | 1,483 | 0.3 | |||

| Stephanie Dilba | mut | 1,267 | 0.2 | |||

| Cetin Oraner | Together Bavaria | 819 | 0.2 | |||

| Valid votes | 542,733 | 99.6 | 560,629 | 99.7 | ||

| Invalid votes | 1,997 | 0.4 | 1,616 | 0.3 | ||

| Total | 544,730 | 100.0 | 562,245 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 1,110,571 | 49.0 | 1,109,032 | 50.7 | ||

| Source: Wahlen München (1st round, 2nd round) |

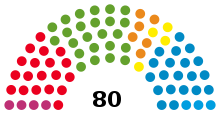

City council[edit]

The Munich city council (Stadtrat) governs the city alongside the Mayor. The most recent city council election was held on 15 March 2020, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Lead candidate | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | Katrin Habenschaden | 11,762,516 | 29.1 | 23 | |||

| Christian Social Union (CSU) | Kristina Frank | 9,986,014 | 24.7 | 20 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | Dieter Reiter | 8,884,562 | 22.0 | 18 | |||

| Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP) | Tobias Ruff | 1,598,539 | 4.0 | 3 | |||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | Iris Wassill | 1,559,476 | 3.9 | 3 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | Jörg Hoffmann | 1,420,194 | 3.5 | 3 | ±0 | ||

| The Left (Die Linke) | Stefan Jagel | 1,319,464 | 3.3 | 3 | |||

| Free Voters of Bavaria (FW) | Hans-Peter Mehling | 1,008,400 | 2.5 | 2 | ±0 | ||

| Volt Germany (Volt) | Felix Sproll | 732,853 | 1.8 | New | 1 | New | |

| Die PARTEI (PARTEI) | Marie Burneleit | 528,949 | 1.3 | New | 1 | New | |

| Pink List (Rosa Liste)[69] | Thomas Niederbühl | 396,324 | 1.0 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Munich List | Dirk Höpner | 339,705 | 0.8 | New | 1 | New | |

| Bavaria Party (BP) | Richard Progl | 273,737 | 0.7 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| mut | Stephanie Dilba | 247,679 | 0.6 | New | 0 | New | |

| FAIR | Kemal Orak | 142,455 | 0.4 | New | 0 | New | |

| Together Bavaria (ZuBa) | Cetin Oraner | 120,975 | 0.3 | New | 0 | New | |

| BIA | Karl Richter | 86,358 | 0.2 | 0 | ±0 | ||

| Valid votes | 531,527 | 97.6 | |||||

| Invalid votes | 12,937 | 2.4 | |||||

| Total | 544,464 | 100.0 | 80 | ±0 | |||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 1,110,571 | 49.0 | |||||

| Source: Wahlen München |

State Landtag[edit]

In the Landtag of Bavaria, Munich is divided between nine constituencies. After the 2018 Bavarian state election, the composition and representation of each was as follows:

| Constituency | Area | Party | Member | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 München-Hadern |

|

CSU | Georg Eisenreich | |

| 102 München-Bogenhausen |

|

CSU | Robert Brannekämper | |

| 103 München-Giesing |

|

GRÜNE | Gülseren Demirel | |

| 104 München-Milbertshofen |

|

GRÜNE | Katharina Schulze | |

| 105 München-Moosach |

|

GRÜNE | Benjamin Adjei | |

| 106 München-Pasing |

|

CSU | Josef Schmid | |

| 107 München-Ramersdorf |

|

CSU | Markus Blume | |

| 108 München-Schwabing |

|

GRÜNE | Christian Hierneis | |

| 109 München-Mitte |

|

GRÜNE | Ludwig Hartmann |

Federal parliament[edit]

In the Bundestag, Munich is divided between four constituencies. In the 20th Bundestag, the composition and representation of each was as follows:

| Constituency | Area | Party | Member | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 217 Munich North |

|

CSU | Bernhard Loos | |

| 218 Munich East |

|

CSU | Wolfgang Stefinger | |

| 219 Munich South |

|

GRÜNE | Jamila Schäfer | |

| 220 Munich West/Centre |

|

CSU | Stephan Pilsinger |

Sister cities[edit]

Plaque in the Neues Rathaus (New City Hall) showing Munich’s twin towns and sister cities

Munich is twinned with the following cities (date of agreement shown in parentheses):[70] Edinburgh, Scotland (1954),[71][72] Verona, Italy (March 17, 1960),[73][74] Bordeaux, France (1964),[75][76] Sapporo, Japan (1972),[77] Cincinnati, Ohio, United States (1989), Kyiv, Ukraine (1989), Harare, Zimbabwe (1996) and Beersheba, Israel (2022).

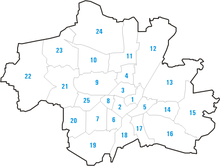

Subdivisions[edit]

Since the administrative reform in 1992, Munich is divided into 25 boroughs or Stadtbezirke, which themselves consist of smaller quarters.

Allach-Untermenzing (23), Altstadt-Lehel (1), Aubing-Lochhausen-Langwied (22), Au-Haidhausen (5), Berg am Laim (14), Bogenhausen (13), Feldmoching-Hasenbergl (24), Hadern (20), Laim (25), Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt (2), Maxvorstadt (3), Milbertshofen-Am Hart (11), Moosach (10), Neuhausen-Nymphenburg (9), Obergiesing (17), Pasing-Obermenzing (21), Ramersdorf-Perlach (16), Schwabing-Freimann (12), Schwabing-West (4), Schwanthalerhöhe (8), Sendling (6), Sendling-Westpark (7), Thalkirchen-Obersendling-Forstenried-Fürstenried-Solln (19), Trudering-Riem (15) and Untergiesing-Harlaching (18).

Architecture[edit]

Viktualienmarkt with the Altes Rathaus

The city has an eclectic mix of historic and modern architecture because historic buildings destroyed in World War II were reconstructed, and new landmarks were built. A survey by the Society’s Centre for Sustainable Destinations for the National Geographic Traveller chose over 100 historic destinations around the world and ranked Munich 30th.[78]

Inner city[edit]

At the centre of the city is the Marienplatz – a large open square named after the Mariensäule, a Marian column in its centre – with the Old and the New Town Hall. Its tower contains the Rathaus-Glockenspiel. Three gates of the demolished medieval fortification survive – the Isartor in the east, the Sendlinger Tor in the south and the Karlstor in the west of the inner city. The Karlstor leads up to the Stachus, a square dominated by the Justizpalast (Palace of Justice) and a fountain.

The Peterskirche close to Marienplatz is the oldest church of the inner city. It was first built during the Romanesque period, and was the focus of the early monastic settlement in Munich before the city’s official foundation in 1158. Nearby St. Peter the Gothic hall-church Heiliggeistkirche (The Church of the Holy Spirit) was converted to baroque style from 1724 onwards and looks down upon the Viktualienmarkt.

The Frauenkirche serves as the cathedral for the Catholic Archdiocese of Munich and Freising. The nearby Michaelskirche is the largest renaissance church north of the Alps, while the Theatinerkirche is a basilica in Italianate high baroque, which had a major influence on Southern German baroque architecture. Its dome dominates the Odeonsplatz. Other baroque churches in the inner city include the Bürgersaalkirche, the Trinity Church and the St. Anna Damenstiftskirche. The Asamkirche was endowed and built by the Brothers Asam, pioneering artists of the rococo period.

The large Residenz palace complex (begun in 1385) on the edge of Munich’s Old Town, Germany’s largest urban palace, ranks among Europe’s most significant museums of interior decoration. Having undergone several extensions, it contains also the treasury and the splendid rococo Cuvilliés Theatre. Next door to the Residenz the neo-classical opera, the National Theatre was erected. Among the baroque and neoclassical mansions which still exist in Munich are the Palais Porcia, the Palais Preysing, the Palais Holnstein and the Prinz-Carl-Palais. All mansions are situated close to the Residenz, same as the Alte Hof, a medieval castle and first residence of the Wittelsbach dukes in Munich.

Lehel, a middle-class quarter east of the Altstadt, is characterised by numerous well-preserved townhouses. The St. Anna im Lehel is the first rococo church in Bavaria. St. Lukas is the largest Protestant Church in Munich.

Royal avenues and squares[edit]

Four grand royal avenues of the 19th century with official buildings connect Munich’s inner city with its then-suburbs:

The neoclassical Brienner Straße, starting at Odeonsplatz on the northern fringe of the Old Town close to the Residenz, runs from east to west and opens into the Königsplatz, designed with the «Doric» Propyläen, the «Ionic» Glyptothek and the «Corinthian» State Museum of Classical Art, behind it St. Boniface’s Abbey was erected. The area around Königsplatz is home to the Kunstareal, Munich’s gallery and museum quarter (as described below).

Ludwigstraße also begins at Odeonsplatz and runs from south to north, skirting the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, the St. Louis church, the Bavarian State Library and numerous state ministries and palaces. The southern part of the avenue was constructed in Italian renaissance style, while the north is strongly influenced by Italian Romanesque architecture. The

Siegestor (gate of victory) sits at the northern end of Ludwigstraße, where the latter passes over into Leopoldstraße and the district of Schwabing begins.

The neo-Gothic Maximilianstraße starts at Max-Joseph-Platz, where the Residenz and the National Theatre are situated, and runs from west to east. The avenue is framed by elaborately structured neo-Gothic buildings which house, among others, the Schauspielhaus, the Building of the district government of Upper Bavaria and the Museum of Ethnology. After crossing the river Isar, the avenue circles the Maximilianeum, which houses the state parliament. The western portion of Maximilianstraße is known for its designer shops, luxury boutiques, jewellery stores, and one of Munich’s foremost five-star hotels, the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten.

Prinzregentenstraße runs parallel to Maximilianstraße and begins at Prinz-Carl-Palais. Many museums are on the avenue, such as the Haus der Kunst, the Bavarian National Museum and the Schackgalerie. The avenue crosses the Isar and circles the Friedensengel monument, then passing the Villa Stuck and Hitler’s old apartment. The Prinzregententheater is at Prinzregentenplatz further to the east.

Other boroughs[edit]

In Schwabing and Maxvorstadt, many beautiful streets with continuous rows of Gründerzeit buildings can be found. Rows of elegant town houses and spectacular urban palais in many colours, often elaborately decorated with ornamental details on their façades, make up large parts of the areas west of Leopoldstraße (Schwabing’s main shopping street), while in the eastern areas between Leopoldstraße and Englischer Garten similar buildings alternate with almost rural-looking houses and whimsical mini-castles, often decorated with small towers. Numerous tiny alleys and shady lanes connect the larger streets and little plazas of the area, conveying the legendary artist’s quarter’s flair and atmosphere convincingly like it was at the turn of the 20th century. The wealthy district of Bogenhausen in the east of Munich is another little-known area (at least among tourists) rich in extravagant architecture, especially around Prinzregentenstraße. One of Bogenhausen’s most beautiful buildings is Villa Stuck, famed residence of painter Franz von Stuck.

Two large Baroque palaces in Nymphenburg and Oberschleissheim are reminders of Bavaria’s royal past. Schloss Nymphenburg (Nymphenburg Palace), some 6 km (4 mi) north west of the city centre, is surrounded by an park and is considered[by whom?] to be one of Europe’s most beautiful royal residences. 2 km (1 mi) northwest of Nymphenburg Palace is Schloss Blutenburg (Blutenburg Castle), an old ducal country seat with a late-Gothic palace church. Schloss Fürstenried (Fürstenried Palace), a baroque palace of similar structure to Nymphenburg but of much smaller size, was erected around the same time in the south west of Munich.

The second large Baroque residence is Schloss Schleissheim (Schleissheim Palace), located in the suburb of Oberschleissheim, a palace complex encompassing three separate residences: Altes Schloss Schleissheim (the old palace), Neues Schloss Schleissheim (the new palace) and Schloss Lustheim (Lustheim Palace). Most parts of the palace complex serve as museums and art galleries. Deutsches Museum’s Flugwerft Schleissheim flight exhibition centre is located nearby, on the Schleissheim Special Landing Field. The Bavaria statue before the neo-classical Ruhmeshalle is a monumental, bronze sand-cast 19th-century statue at Theresienwiese. The Grünwald castle is the only medieval castle in the Munich area which still exists.

St Michael in Berg am Laim is a church in the suburbs. Another church of Johann Michael Fischer is St George in Bogenhausen. Most of the boroughs have parish churches that originate from the Middle Ages, such as the church of pilgrimage St Mary in Ramersdorf. The oldest church within the city borders is Heilig Kreuz in Fröttmaning next to the Allianz Arena, known for its Romanesque fresco. Moosach features one of the oldest churches, Alt-St. Martin, but a larger one was built in 1925.

Especially in its suburbs, Munich features a wide and diverse array of modern architecture, although strict culturally sensitive height limitations for buildings have limited the construction of skyscrapers to avoid a loss of views to the distant Bavarian Alps. Most high-rise buildings are clustered at the northern edge of Munich in the skyline, like the Hypo-Haus, the Arabella High-Rise Building, the Highlight Towers, Uptown Munich, Münchner Tor and the BMW Headquarters next to the Olympic Park. Several other high-rise buildings are located near the city centre and on the Siemens campus in southern Munich. A landmark of modern Munich is also the architecture of the sport stadiums (as described below).

In Fasangarten is the former McGraw Kaserne, a former US army base, near Stadelheim Prison.

Parks[edit]

Hofgarten with the dome of the state chancellery near the Residenz

Munich is a densely-built city but has numerous public parks. In 1789, the Englischer Garten was created just north of Munich’s old city center. Covering an area of 3.7 km2 (1.4 sq mi), it is larger than Central Park in New York City, and it is one of the world’s largest urban public parks.[79] It contains a naturist (nudist) area, numerous bicycle and jogging tracks as well as bridle-paths. It was designed and laid out by Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, both for pleasure and as a work area for the city’s vagrants and homeless. Nowadays it is entirely a park, its southern half being dominated by wide-open areas, hills, monuments and beach-like stretches (along the streams Eisbach and Schwabinger Bach). In contrast, its less-frequented northern part is much quieter, with many old trees and thick undergrowth. Multiple beer gardens can be found in both parts of the Englischer Garten, the most well-known being located at the Chinese Pagoda.

Other large green spaces are the modern Olympiapark, the Westpark, and the parks of Nymphenburg Palace (with the Botanischer Garten München-Nymphenburg to the north), and Schleissheim Palace. The city’s oldest park is the Hofgarten, near the Residenz, dating back to the 16th century. The site of the largest beer garden in town, the former royal Hirschgarten was founded in 1780 for deer, which still live there.

The city’s zoo is the Tierpark Hellabrunn near the Flaucher Island in the Isar in the south of the city. Another notable park is Ostpark located in the Ramersdorf-Perlach borough which also houses the Michaelibad, the largest water park in Munich.

Sports[edit]

Olympiasee in Olympiapark, Munich

Football[edit]

Munich is home to several professional football teams including Bayern Munich, Germany’s most successful club and a multiple UEFA Champions League winner. Other notable clubs include 1860 Munich, who were long time their rivals on a somewhat equal footing, but currently play in the 3rd Division 3. Liga, and former Bundesliga club SpVgg Unterhaching, who currently play in the Regionalliga Bayern, in Germany’s 4th division.

Basketball[edit]

FC Bayern Munich Basketball is currently playing in the Beko Basket Bundesliga. The city hosted the final stages of the FIBA EuroBasket 1993, where the German national basketball team won the gold medal.

Ice hockey[edit]

The city’s ice hockey club is EHC Red Bull München who play in the Deutsche Eishockey Liga. The team has won three DEL Championships, in 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Olympics[edit]

Munich hosted the 1972 Summer Olympics; the Munich Massacre took place in the Olympic village. It was one of the host cities for the 2006 Football World Cup, which was not held in Munich’s Olympic Stadium, but in a new football specific stadium, the Allianz Arena. Munich bid to host the 2018 Winter Olympic Games, but lost to Pyeongchang.[80] In September 2011 the DOSB President Thomas Bach confirmed that Munich would bid again for the Winter Olympics in the future.[81] These plans were abandoned some time later.

Road running[edit]

Regular annual road running events in Munich are the Munich Marathon in October, the Stadtlauf end of June, the company run B2Run in July, the New Year’s Run on 31 December, the Spartan Race Sprint, the Olympia Alm Crosslauf and the Bestzeitenmarathon.

Swimming[edit]

Public sporting facilities in Munich include ten indoor swimming pools[82] and eight outdoor swimming pools,[83] which are operated by the Munich City Utilities (SWM) communal company.[84] Popular indoor swimming pools include the Olympia Schwimmhalle of the 1972 Summer Olympics, the wave pool Cosimawellenbad, as well as the Müllersches Volksbad which was built in 1901. Further, swimming within Munich’s city limits is also possible in several artificial lakes such as for example the Riemer See or the Langwieder lake district.[85]

River surfing[edit]

Munich has a reputation as a surfing hotspot, offering the world’s best known river surfing spot, the Eisbach wave, which is located at the southern edge of the Englischer Garten park and used by surfers day and night and throughout the year.[86] Half a kilometre down the river, there is a second, easier wave for beginners, the so-called Kleine Eisbachwelle. Two further surf spots within the city are located along the river Isar, the wave in the Floßlände channel and a wave downstream of the Wittelsbacherbrücke bridge.[87]

Other Sports[edit]

Starting in 2023, Munich will have a team enter into the European League of Football, a professional American football league with teams throughout Europe.[citation needed]

Culture[edit]

Language[edit]

The Bavarian dialects are spoken in and around Munich, with its variety West Middle Bavarian or Old Bavarian (Westmittelbairisch / Altbairisch). Austro-Bavarian has no official status by the Bavarian authorities or local government, yet is recognised by the SIL and has its own ISO-639 code.

Museums[edit]

The Deutsches Museum or German Museum, located on an island in the River Isar, is the largest and one of the oldest science museums in the world. Three redundant exhibition buildings that are under a protection order were converted to house the Verkehrsmuseum, which houses the land transport collections of the Deutsches Museum. Deutsches Museum’s Flugwerft Schleissheim flight exhibition centre is located nearby, on the Schleissheim Special Landing Field. Several non-centralised museums (many of those are public collections at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität) show the expanded state collections of palaeontology, geology, mineralogy,[88] zoology, botany and anthropology.

The city has several important art galleries, most of which can be found in the Kunstareal, including the Alte Pinakothek, the Neue Pinakothek, the Pinakothek der Moderne and the Museum Brandhorst. The Alte Pinakothek contains a treasure trove of the works of European masters between the 14th and 18th centuries. The collection reflects the eclectic tastes of the Wittelsbachs over four centuries and is sorted by schools over two floors. Major displays include Albrecht Dürer’s Christ-like Self-Portrait (1500), his Four Apostles, Raphael’s paintings The Canigiani Holy Family and Madonna Tempi as well as Peter Paul Rubens large Judgment Day. The gallery houses one of the world’s most comprehensive Rubens collections. The Lenbachhaus houses works by the group of Munich-based modernist artists known as Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider).

An important collection of Greek and Roman art is held in the Glyptothek and the Staatliche Antikensammlung (State Antiquities Collection). King Ludwig I managed to acquire such pieces as the Medusa Rondanini, the Barberini Faun and figures from the Temple of Aphaea on Aegina for the Glyptothek. Another important museum in the Kunstareal is the Egyptian Museum.

The gothic Morris dancers of Erasmus Grasser are exhibited in the Munich City Museum in the old gothic arsenal building in the inner city.

Another area for the arts next to the Kunstareal is the Lehel quarter between the old town and the river Isar: the Museum Five Continents in Maximilianstraße is the second largest collection in Germany of artefacts and objects from outside Europe, while the Bavarian National Museum and the adjoining Bavarian State Archaeological Collection in Prinzregentenstraße rank among Europe’s major art and cultural history museums. The nearby Schackgalerie is an important gallery of German 19th-century paintings.

The former Dachau concentration camp is 16 km (10 mi) outside the city.

Arts and literature[edit]

Munich is a major international cultural centre and has played host to many prominent composers including Orlando di Lasso, W.A. Mozart, Carl Maria von Weber, Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Max Reger and Carl Orff. With the Munich Biennale founded by Hans Werner Henze, and the A*DEvantgarde festival, the city still contributes to modern music theatre. Some of classical music’s best-known pieces have been created in and around Munich by composers born in the area, for example, Richard Strauss’s tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra or Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana.

At the Nationaltheater several of Richard Wagner’s operas were premiered under the patronage of Ludwig II of Bavaria. It is the home of the Bavarian State Opera and the Bavarian State Orchestra. Next door, the modern Residenz Theatre was erected in the building that had housed the Cuvilliés Theatre before World War II. Many operas were staged there, including the premiere of Mozart’s Idomeneo in 1781. The Gärtnerplatz Theatre is a ballet and musical state theatre while another opera house, the Prinzregententheater, has become the home of the Bavarian Theatre Academy and the Munich Chamber Orchestra.

The modern Gasteig centre houses the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra. The third orchestra in Munich with international importance is the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Its primary concert venue is the Herkulessaal in the former city royal residence, the Munich Residenz. Many important conductors have been attracted by the city’s orchestras, including Felix Weingartner, Hans Pfitzner, Hans Rosbaud, Hans Knappertsbusch, Sergiu Celibidache, James Levine, Christian Thielemann, Lorin Maazel, Rafael Kubelík, Eugen Jochum, Sir Colin Davis, Mariss Jansons, Bruno Walter, Georg Solti, Zubin Mehta and Kent Nagano. A stage for shows, big events and musicals is the Deutsche Theater. It is Germany’s largest theatre for guest performances.[citation needed]

Munich’s contributions to modern popular music are often overlooked in favour of its strong association with classical music, but they are numerous: the city has had a strong music scene in the 1960s and 1970s, with many internationally renowned bands and musicians frequently performing in its clubs.[citation needed]

Furthermore, Munich was the centre of Krautrock in southern Germany, with many important bands such as Amon Düül II, Embryo or Popol Vuh hailing from the city. In the 1970s, the Musicland Studios developed into one of the most prominent recording studios in the world, with bands such as the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and Queen recording albums there. Munich also played a significant role in the development of electronic music, with genre pioneer Giorgio Moroder, who invented synth disco and electronic dance music, and Donna Summer, one of disco music’s most important performers, both living and working in the city. In the late 1990s, Electroclash was substantially co-invented if not even invented in Munich, when DJ Hell introduced and assembled international pioneers of this musical genre through his International DeeJay Gigolo Records label here.[89]

Other notable musicians and bands from Munich include Konstantin Wecker, Willy Astor, Spider Murphy Gang, Münchener Freiheit, Lou Bega, Megaherz, FSK, Colour Haze and Sportfreunde Stiller.

Music is so important in the Bavarian capital that the city hall gives permissions every day to ten musicians for performing in the streets around Marienplatz. This is how performers such as Olga Kholodnaya and Alex Jacobowitz are entertaining the locals and the tourists every day.[citation needed]

Next to the Bavarian Staatsschauspiel in the Residenz Theatre (Residenztheater), the Munich Kammerspiele in the Schauspielhaus is one of the most important German-language theatres in the world. Since Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s premieres in 1775 many important writers have staged their plays in Munich such as Christian Friedrich Hebbel, Henrik Ibsen and Hugo von Hofmannsthal.[citation needed]

The city is known as the second-largest publishing centre in the world (around 250 publishing houses have offices in the city), and many national and international publications are published in Munich, such as Arts in Munich, LAXMag and Prinz.[citation needed]

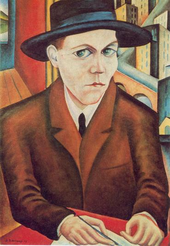

At the turn of the 20th century, Munich, and especially its suburb of Schwabing, was the preeminent cultural metropolis of Germany. Its importance as a centre for both literature and the fine arts was second to none in Europe, with numerous German and non-German artists moving there. For example, Wassily Kandinsky chose Munich over Paris to study at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste München, and, along with many other painters and writers living in Schwabing at that time, had a profound influence on modern art.[citation needed]

Prominent literary figures worked in Munich especially during the final decades of the Kingdom of Bavaria, the so-called Prinzregentenzeit (literally «prince regent’s time») under the reign of Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria, a period often described as a cultural Golden Age for both Munich and Bavaria as a whole. Some of the most notable were Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Paul Heyse, Rainer Maria Rilke, Ludwig Thoma, Fanny zu Reventlow, Oskar Panizza, Gustav Meyrink, Max Halbe, Erich Mühsam and Frank Wedekind.

For a short while, Vladimir Lenin lived in Schwabing, where he wrote and published his most important work, What Is to Be Done? Central to Schwabing’s bohemian scene (although they were actually often located in the nearby Maxvorstadt quarter) were Künstlerlokale (artist’s cafés) like Café Stefanie or Kabarett Simpl, whose liberal ways differed fundamentally from Munich’s more traditional localities. The Simpl, which survives to this day (although with little relevance to the city’s contemporary art scene), was named after Munich’s anti-authoritarian satirical magazine Simplicissimus, founded in 1896 by Albert Langen and Thomas Theodor Heine, which quickly became an important organ of the Schwabinger Bohème. Its caricatures and biting satirical attacks on Wilhelmine German society were the result of countless of collaborative efforts by many of the best visual artists and writers from Munich and elsewhere.[citation needed]

The period immediately before World War I saw continued economic and cultural prominence for the city. Thomas Mann wrote in his novella Gladius Dei about this period: «München leuchtete» (literally «Munich shone»). Munich remained a centre of cultural life during the Weimar period, with figures such as Lion Feuchtwanger, Bertolt Brecht, Peter Paul Althaus, Stefan George, Ricarda Huch, Joachim Ringelnatz, Oskar Maria Graf, Annette Kolb, Ernst Toller, Hugo Ball and Klaus Mann adding to the already established big names. Karl Valentin was Germany’s most important cabaret performer and comedian and is to this day well-remembered and beloved as a cultural icon of his hometown. Between 1910 and 1940, he wrote and performed in many absurdist sketches and short films that were highly influential, earning him the nickname of «Charlie Chaplin of Germany». Many of Valentin’s works wouldn’t be imaginable without his congenial female partner Liesl Karlstadt, who often played male characters to hilarious effect in their sketches. After World War II, Munich soon again became a focal point of the German literary scene and remains so to this day, with writers as diverse as Wolfgang Koeppen, Erich Kästner, Eugen Roth, Alfred Andersch, Elfriede Jelinek, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Michael Ende, Franz Xaver Kroetz, Gerhard Polt and Patrick Süskind calling the city their home.[citation needed]

From the Gothic to the Baroque era, the fine arts were represented in Munich by artists like Erasmus Grasser, Jan Polack, Johann Baptist Straub, Ignaz Günther, Hans Krumpper, Ludwig von Schwanthaler, Cosmas Damian Asam, Egid Quirin Asam, Johann Baptist Zimmermann, Johann Michael Fischer and François de Cuvilliés. Munich had already become an important place for painters like Carl Rottmann, Lovis Corinth, Wilhelm von Kaulbach, Carl Spitzweg, Franz von Lenbach, Franz von Stuck, Karl Piloty and Wilhelm Leibl when Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a group of expressionist artists, was established in Munich in 1911. The city was home to the Blue Rider’s painters Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, Gabriele Münter, Franz Marc, August Macke and Alfred Kubin. Kandinsky’s first abstract painting was created in Schwabing.[citation needed]

Munich was (and in some cases, still is) home to many of the most important authors of the New German Cinema movement, including Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, Edgar Reitz and Herbert Achternbusch. In 1971, the Filmverlag der Autoren was founded, cementing the city’s role in the movement’s history. Munich served as the location for many of Fassbinder’s films, among them Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. The Hotel Deutsche Eiche near Gärtnerplatz was somewhat like a centre of operations for Fassbinder and his «clan» of actors. New German Cinema is considered by far the most important artistic movement in German cinema history since the era of German Expressionism in the 1920s.[citation needed]

In 1919, the Bavaria Film Studios were founded, which developed into one of Europe’s largest film studios. Directors like Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, Orson Welles, John Huston, Ingmar Bergman, Stanley Kubrick, Claude Chabrol, Fritz Umgelter, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wolfgang Petersen and Wim Wenders made films there. Among the internationally well-known films produced at the studios are The Pleasure Garden (1925) by Alfred Hitchcock, The Great Escape (1963) by John Sturges, Paths of Glory (1957) by Stanley Kubrick, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971) by Mel Stuart and both Das Boot (1981) and The Neverending Story (1984) by Wolfgang Petersen. Munich remains one of the centres of the German film and entertainment industry.[citation needed]

Festivals[edit]

Annual «High End Munich» trade show.[90]

Starkbierfest[edit]

March and April, city-wide:[91] Starkbierfest is held for three weeks during Lent, between Carnival and Easter,[92] celebrating Munich’s “strong beer”. Starkbier was created in 1651 by the local Paulaner monks who drank this ‘Flüssiges Brot’, or ‘liquid bread’ to survive the fasting of Lent.[92] It became a public festival in 1751 and is now the second largest beer festival in Munich.[92] Starkbierfest is also known as the “fifth season”, and is celebrated in beer halls and restaurants around the city.[91]

Frühlingsfest[edit]

April and May, Theresienwiese:[91]

Held for two weeks from the end of April to the beginning of May,[91] Frühlingsfest celebrates spring and the new local spring beers, and is commonly referred to as the «little sister of Oktoberfest».[93] There are two beer tents, Hippodrom and Festhalle Bayernland, as well as one roofed beer garden, Münchner Weißbiergarten.[94] There are also roller coasters, fun houses, slides, and a Ferris wheel. Other attractions of the festival include a flea market on the festival’s first Saturday, a “Beer Queen” contest, a vintage car show on the first Sunday, fireworks every Friday night, and a «Day of Traditions» on the final day.[94]

Auer Dult[edit]

May, August, and October, Mariahilfplatz:[91] Auer Dult is Europe’s largest jumble sale, with fairs of its kind dating back to the 14th century.[95] The Auer Dult is a traditional market with 300 stalls selling handmade crafts, household goods, and local foods, and offers carnival rides for children. It has taken place over nine days each, three times a year. since 1905.[91][95]

Kocherlball[edit]

July, English Garden:[91]

Traditionally a ball for Munich’s domestic servants, cooks, nannies, and other household staff, Kocherlball, or ‘cook’s ball’ was a chance for the lower classes to take the morning off and dance together before the families of their households woke up.[91] It now runs between 6 and 10 am the third Sunday in July at the Chinese Tower in Munich’s English Garden.[96]

Tollwood[edit]

July and December, Olympia Park:[97] For three weeks in July, and then three weeks in December, Tollwood showcases fine and performing arts with live music, circus acts, and several lanes of booths selling handmade crafts, as well as organic international cuisine.[91] According to the festival’s website, Tollwood’s goal is to promote culture and the environment, with the main themes of «tolerance, internationality, and openness».[98] To promote these ideals, 70% of all Tollwood events and attractions are free.[98]

Oktoberfest[edit]

September and October, Theresienwiese:[91] The largest beer festival in the world, Munich’s Oktoberfest runs for 16–18 days from the end of September through early October.[99] Oktoberfest is a celebration of the wedding of Bavarian Crown Prince Ludwig to Princess Therese of Saxony-Hildburghausen which took place on 12 October 1810.[100] In the last 200 years the festival has grown to span 85 acres and now welcomes over 6 million visitors every year.[99] There are 14 beer tents which together can seat 119,000 attendees at a time,[99] and serve beer from the six major breweries of Munich: Augustiner, Hacker-Pschorr, Löwenbräu, Paulaner, Spaten and Staatliches Hofbräuhaus.[100] Over 7 million liters of beer are consumed at each Oktoberfest.[99] There are also over 100 rides ranging from bumper cars to full-sized roller coasters, as well as the more traditional Ferris wheels and swings.[100] Food can be bought in each tent, as well as at various stalls throughout the fairgrounds. Oktoberfest hosts 144 caterers and employees 13,000 people.[99]

Christkindlmarkt[edit]

November and December, city-wide:[91] Munich’s Christmas Markets, or Christkindlmärkte, are held throughout the city from late November until Christmas Eve, the largest spanning the Marienplatz and surrounding streets.[91] There are hundreds of stalls selling handmade goods, Christmas ornaments and decorations, and Bavarian Christmas foods including pastries, roasted nuts, and gluwein.[91]

Mini-Munich[edit]

Late-July to mid-August, city-wide: Mini-Munich provides kids ages 7–15 with the opportunity to participate in a Spielstadt, the German term for a miniature city composed almost entirely of children. Funded by Kultur & Spielraum, this play city is run by young Germans performing the same duties as adults, including voting in city council, paying taxes, and building businesses. The experimental game was invented in Munich in the 1970s and has since spread to other countries like Egypt and China.

Coopers’ Dance[edit]

The Coopers’ Dance (German: Schäfflertanz) is a guild dance of coopers originally started in Munich. Since early 1800s the custom spread via journeymen in it is now a common tradition over the Old Bavaria region. The dance was supposed to be held every 7 years.[101]

Cultural history trails and bicycle routes[edit]

Since 2001, historically interesting places in Munich can be explored via the cultural history trails (KulturGeschichtsPfade). Sign-posted cycle routes are the Outer Äußere Radlring (outer cycle route) and the RadlRing München.[102]

Cuisine and culinary specialities[edit]

The Munich cuisine contributes to the Bavarian cuisine. Munich Weisswurst («white sausage», German: Münchner Weißwurst) was invented here in 1857. It is a Munich speciality. Traditionally eaten only before noon – a tradition dating to a time before refrigerators – these morsels are often served with sweet mustard and freshly baked pretzels.

Munich offers 11 restaurants that have been awarded one or more Michelin stars in the Michelin Guide of 2021.[103]

Beers and breweries[edit]

Munich is known for its breweries and the Weissbier (or Weißbier / Weizenbier, wheat beer) is a speciality from Bavaria. Helles, a pale lager with a translucent gold colour is the most popular Munich beer today, although it’s not old (only introduced in 1895) and is the result of a change in beer tastes. Helles has largely replaced Munich’s dark beer, Dunkles, which gets its colour from roasted malt. It was the typical beer in Munich in the 19th century, but it is now more of a speciality. Starkbier is the strongest Munich beer, with 6%–9% alcohol content. It is dark amber in colour and has a heavy malty taste. It is available and is sold particularly during the Lenten Starkbierzeit (strong beer season), which begins on or before St. Joseph’s Day (19 March). The beer served at Oktoberfest is a special type of Märzen beer with a higher alcohol content than regular Helles.

There are countless Wirtshäuser (traditional Bavarian ale houses/restaurants) all over the city area, many of which also have small outside areas. Biergärten (beer gardens) are popular fixtures of Munich’s gastronomic landscape. They are central to the city’s culture and serve as a kind of melting pot for members of all walks of life, for locals, expatriates and tourists alike. It is allowed to bring one’s own food to a beer garden, however, it is forbidden to bring one’s own drinks. There are many smaller beer gardens and around twenty major ones, providing at least a thousand seats, with four of the largest in the Englischer Garten: Chinesischer Turm (Munich’s second-largest beer garden with 7,000 seats), Seehaus, Hirschau and Aumeister. Nockherberg, Hofbräukeller (not to be confused with the Hofbräuhaus) and Löwenbräukeller are other beer gardens. Hirschgarten is the largest beer garden in the world, with 8,000 seats.

There are six main breweries in Munich: Augustiner-Bräu, Hacker-Pschorr, Hofbräu, Löwenbräu, Paulaner and Spaten-Franziskaner-Bräu (separate brands Spaten and Franziskaner, the latter of which mainly for Weissbier).

Also much consumed, though not from Munich and thus without the right to have a tent at the Oktoberfest, are Tegernseer and Schneider Weisse, the latter of which has a major beer hall in Munich. Smaller breweries are becoming more prevalent in Munich, such as Giesinger Bräu.[104] However, these breweries do not have tents at Oktoberfest.

Circus[edit]

The Circus Krone based in Munich is one of the largest circuses in Europe.[105] It was the first and still is one of only a few in Western Europe to also occupy a building of its own.

Nightlife[edit]

Nightlife in Munich is located mostly in the boroughs Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt, Maxvorstadt, Au-Haidhausen, Berg am Laim and Sendling. Between Sendlinger Tor and Maximiliansplatz, on the edge of the central Altstadt-Lehel district, there is also the so-called Feierbanane (party banana), a roughly banana-shaped unofficial party zone spanning 1.3 km (0.8 mi) along Sonnenstraße, characterized by a high concentration of clubs, bars and restaurants, which became the center of Munich’s nightlife in the mid-2000s.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Schwabing was considered a center of nightlife in Germany, with internationally known clubs such as Big Apple, PN hit-house, Domicile, Hot Club, Piper Club, Tiffany, Germany’s first large-scale discotheque Blow Up and the underwater nightclub Yellow Submarine,[89][106][107] and Munich has been called «New York’s big disco sister» in this context.[89][108] Bars in the Schwabing district of this era include, among many others, Schwabinger 7 and Schwabinger Podium. Since the 1980s, however, Schwabing has lost much of its nightlife activity due to gentrification and the resulting high rents, and the formerly wild artists’ and students’ quarter developed into one of the city’s most coveted and expensive residential districts, attracting affluent citizens with little interest in partying.

Since the 1960s, the Rosa Viertel (pink quarter) developed in the Glockenbachviertel and around Gärtnerplatz, which in the 1980s made Munich «one of the four gayest metropolises in the world» along with San Francisco, New York City and Amsterdam.[109] In particular, the area around Müllerstraße and Hans-Sachs-Straße was characterized by numerous gay bars and nightclubs. One of them was the travesty nightclub Old Mrs. Henderson, where Freddie Mercury, who lived in Munich from 1979 to 1985, filmed the music video for the song Living on My Own at his 39th birthday party.[109][107][110] Transsexual icon Romy Haag had a club in the city centre for many years.[citation needed]