Robot Visions / Я — робот

- Описание

- Обсуждения

- Цитаты 1

- Рецензии

- Коллекции

В конце 1940-х и начале 1950-х Айзек Азимов начинает печатать свои фантастические рассказы на страницах журналов. Вторая мировая война только что завершилась и мир одержим технологическим возрождением. Рассказы писателя отражали озабоченность общества по поводу опасностей от передовых технологий.

Три закона робототехники:

1) Робот не может причинить вред человеку или своим бездействием допустить, чтобы человеку причинили вред

2) Робот обязан подчинятся приказам человека, за исключением тех случаев, когда такой приказ будет противоречить Первому закону

3) Робот должен заботиться о собственной безопасности до тех пор, пока это не противоречит Первому и Второму законам.

С этих трех положений Айзек Азимов навсегда изменил сознание человечества, готовя нас к будущему, в котором человечество само по себе может оказаться устаревшим.

©MrsGonzo для LibreBook

Попросту говоря, если Байерли исполняет все Законы роботехники, он — или робот, или очень хороший человек.

добавить цитату

Иллюстрации

Видеоанонс

Включить видео youtube.com

Взято c youtube.com.

Пожаловаться, не открывается

- Похожее

-

Рекомендации

-

Ваши комменты

- Еще от автора

Количество закладок

В процессе: 28

Прочитали: 52

В любимых: 19

Закончил? Сделай дело!

Азимов Айзек » Я, робот — читать книгу онлайн бесплатно

Конец бесплатного ознакомительного фрагмента

К сожалению, полный текст книги недоступен для бесплатного чтения в связи с жалобой правообладателя.

Оглавление:

-

Я, робот (пер. А. Д. Иорданского)

1

-

Робби (пер. А. Д. Иорданского)

2

-

Хоровод (пер. А. Д. Иорданского)

10

Настройки:

Ширина: 100%

Выравнивать текст

Айзек Азимов

Я, робот

ТРИ ЗАКОНА РОБОТЕХНИКИ

1. Робот не может причинить вред человеку или своим бездействием допустить, чтобы человеку был причинен вред.

2. Робот должен повиноваться всем приказам, которые отдает человек, кроме тех случаев, когда эти приказы противоречат Первому Закону.

3. Робот должен заботиться о своей безопасности в той мере, в какой это не противоречит Первому и Второму Законам.

Isaac Asimov

I, Robot

* * *

Все права защищены. Книга или любая ее часть не может быть скопирована, воспроизведена в электронной или механической форме, в виде фотокопии, записи в память ЭВМ, репродукции или каким-либо иным способом, а также использована в любой информационной системе без получения разрешения от издателя. Копирование, воспроизведение и иное использование книги или ее части без согласия издателя является незаконным и влечет уголовную, административную и гражданскую ответственность.

Copyright © 1950, 1977 by the Estate of Isaac Asimov

© А. Иорданский, перевод на русский язык, 2019

© Н. Сосновская, перевод на русский язык, 2019

© Издание на русском языке, оформление. ООО «Издательство „Эксмо“», 2019

Вступление

(Перевод А. Иорданского)

Я посмотрел свои заметки, и они мне не понравились. Те три дня, которые я провел на предприятиях фирмы «Ю. С. Роботс», я мог бы с таким же успехом просидеть дома, изучая энциклопедию.

Как мне сказали, Сьюзен Кэлвин родилась в 1982 году. Значит, теперь ей семьдесят пять. Это известно каждому. Фирме «Ю. С. Роботс энд Мекэникел Мен Корпорейшн» тоже семьдесят пять лет. Именно в тот год, когда родилась доктор Кэлвин, Лоуренс Робертсби основал предприятие, которое со временем стало самым необыкновенным промышленным гигантом в истории человечества. Но и это тоже известно каждому.

В двадцать лет Сьюзен Кэлвин присутствовала на том самом занятии семинара по психоматематике, когда доктор Альфред Лэннинг из «Ю. С. Роботс» продемонстрировал первого подвижного робота, обладавшего голосом. Этот большой, неуклюжий, уродливый робот, от которого разило машинным маслом, был предназначен для использования в проектировавшихся рудниках на Меркурии. Но он умел говорить, и говорить разумно.

На этом семинаре Сьюзен не выступала. Она не приняла участия и в последовавших за ним бурных дискуссиях. Мир не нравился этой малообщительной, бесцветной и неинтересной девушке с каменным выражением и гипертрофированным интеллектом, и она сторонилась людей.

Но, слушая и наблюдая, она уже тогда почувствовала, как в ней холодным пламенем загорается увлечение.

В 2005 году она окончила Колумбийский университет, поступила в аспирантуру по кибернетике.

Изобретенные Робертсоном позитронные мозговые связи превзошли все достигнутое в середине XX века в области вычислительных машин и совершили настоящий переворот. Целые мили реле и фотоэлементов уступили место пористому платино-иридиевому шару размером с человеческий мозг.

Сьюзен научилась рассчитывать необходимые параметры, определять возможные значения переменных позитронного «мозга» и разрабатывать такие схемы, чтобы можно было точно предсказать его реакцию на данные раздражители.

В 2008 году она получила степень доктора и поступила на «Ю. С. Роботс» в качестве робопсихолога, став, таким образом, первым выдающимся специалистом в этой новой области науки. Лоуренс Робертсон тогда все еще был президентом компании, Альфред Лэннинг – научным руководителем.

За пятьдесят лет на глазах Сьюзен Кэлвин прогресс человечества изменил свое русло и рванулся вперед.

Теперь она уходила в отставку – насколько это вообще было для нее возможно. Во всяком случае, она позволила повесить на двери своего старого кабинета табличку с чужим именем.

Вот, собственно, и все, что было у меня записано. Были еще длинные списки ее печатных работ, принадлежащих ей патентов, точная хронология ее продвижения по службе, – короче, я знал до мельчайших деталей всю ее официальную биографию.

Но мне было нужно другое. Серия очерков для «Интерплэнегери Пресс» требовала большего. Гораздо большего.

Я так ей и сказал.

– Доктор Кэлвин, – сказал я, – для публики вы и «Ю. С. Роботс» – одно и то же. Ваша отставка будет концом целой эпохи.

– Вам нужны живые детали?

Она не улыбнулась. По-моему, она вообще никогда не улыбается. Но ее острый взгляд не был сердитым. Я почувствовал, как он пронизал меня до самого затылка, и понял, что она видит меня насквозь. Она всех видела насквозь. Тем не менее я сказал:

– Совершенно верно.

– Живые детали о роботах? Получается противоречие.

– Нет, доктор. О вас.

– Ну, меня тоже называют роботом. Вам, наверное, уже сказали, что во мне нет ничего человеческого.

Мне это действительно говорили, но я решил промолчать.

Она встала со стула. Она была небольшого роста и выглядела хрупкой.

Вместе с ней я подошел к окну.

Конторы и цеха «Ю. С. Роботс» были похожи на целый маленький, правильно распланированный городок. Он раскинулся перед нами, плоский, как аэрофотография.

– Когда я начала здесь работать, – сказала она, – у меня была маленькая комнатка в здании, которое стояло где-то вон там, где сейчас котельная. Это здание снесли, когда вас не было на свете. В комнате сидели еще три человека. На мою долю приходилось полстола. Все наши роботы производились в одном корпусе. Три штуки в неделю. А посмотрите сейчас!

– Пятьдесят лет – долгий срок. – Я не придумал ничего лучше этой избитой фразы.

– Ничуть, если это ваше прошлое, – возразила она. – Я думаю, как это они так быстро пролетели.

Она снова села за стол. Хотя выражение ее лица не изменилось, но ей, по-моему, стало грустно.

– Сколько вам лет? – поинтересовалась она.

– Тридцать два, – ответил я.

– Тогда вы не помните, каким был мир без роботов. Было время, когда перед лицом Вселенной человек был одинок и не имел друзей. Теперь у него есть помощники, существа более сильные, более надежные, более эффективные, чем он, и абсолютно ему преданные. Человечество больше не одиноко. Вам это не приходило в голову?

– Боюсь, что нет. Можно будет процитировать ваши слова?

– Можно. Для вас робот – это робот. Механизмы и металл, электричество и позитроны. Разум, воплощенный в железе! Создаваемый человеком, а если нужно, и уничтожаемый человеком. Но вы не работали с ними и вы их не знаете. Они чище и лучше нас.

Я попробовал осторожно подзадорить ее.

– Мы были бы рады услышать кое-что из того, что вы знаете о роботах, что вы о них думаете. «Интерплэнетери Пресс» обслуживает всю Солнечную систему. Миллиарды потенциальных слушателей, доктор Кэлвин! Они должны услышать ваш рассказ.

Но подзадоривать ее не приходилось. Не слушая меня, она продолжала:

– Все это можно было предвидеть с самого начала. Тогда мы продавали роботов для использования на Земле – это было еще даже до меня. Конечно, роботы тогда еще не умели говорить. Потом они стали больше похожи на человека и начались протесты. Профсоюзы не хотели, чтобы роботы конкурировали с человеком; религиозные организации возражали из-за своих предрассудков. Все это было смешно и вовсе бесполезно. Но это было.

Я записывал все подряд на свой карманный магнитофон, стараясь незаметно шевелить пальцами. Если немного попрактиковаться, то можно управлять магнитофоном, не вынимая его из кармана.

– Возьмите историю с Робби. Я не знала его. Он был пущен на слом как безнадежно устаревший за год до того, как я поступила на работу. Но я видела девочку в музее.

Она умолкла. Ее глаза затуманились. Я тоже молчал, не мешая ей углубиться в прошлое. Это прошлое было таким далеким!

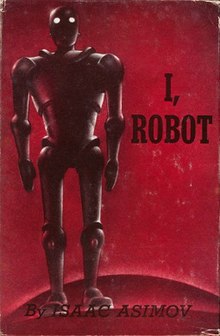

First edition cover |

|

| Author | Isaac Asimov |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Edd Cartier |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Robot series |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Gnome Press |

|

Publication date |

December 2, 1950 |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 253 |

| Followed by | The Complete Robot |

I, Robot is a fixup (compilation) novel of science fiction short stories or essays by American writer Isaac Asimov. The stories originally appeared in the American magazines Super Science Stories and Astounding Science Fiction between 1940 and 1950 and were then compiled into a book for stand-alone (single issue / special edition) publication by Gnome Press in 1950, in an initial edition of 5,000 copies. The stories are woven together by a framing narrative in which the fictional Dr. Susan Calvin tells each story to a reporter (who serves as the narrator) in the 21st century. Although the stories can be read separately, they share a theme of the interaction of humans, robots, and morality, and when combined they tell a larger story of Asimov’s fictional history of robotics.[citation needed]

Several of the stories feature the character of Dr. Calvin, chief robopsychologist at U.S. Robots and Mechanical Men, Inc., the major manufacturer of robots. Upon their publication in this collection, Asimov wrote a framing sequence presenting the stories as Calvin’s reminiscences during an interview with her about her life’s work, chiefly concerned with aberrant behaviour of robots and the use of «robopsychology» to sort out what is happening in their positronic brain. The book also contains the short story in which Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics first appear, which had large influence on later science fiction and had impact on thought on ethics of artificial intelligence as well. Other characters that appear in these short stories are Powell and Donovan, a field-testing team which locates flaws in USRMM’s prototype models.[citation needed]

The collection shares a title with the then recent short story «I, Robot» (1939) by Eando Binder (pseudonym of Earl and Otto Binder), which greatly influenced Asimov. Asimov had wanted to call his collection Mind and Iron and objected when the publisher made the title the same as Binder’s. In his introduction to the story in Isaac Asimov Presents the Great SF Stories (1979), Asimov wrote:

It certainly caught my attention. Two months after I read it, I began «Robbie», about a sympathetic robot, and that was the start of my positronic robot series. Eleven years later, when nine of my robot stories were collected into a book, the publisher named the collection I, Robot over my objections. My book is now the more famous, but Otto’s story was there first.

— Isaac Asimov (1979)[1]

Contents[edit]

- «Introduction» (the initial portion of the framing story or linking text)

- «Robbie» (1940, 1950)

- «Runaround» (1942), novelette

- «Reason» (1941)

- «Catch That Rabbit» (1944)

- «Liar!» (1941)

- «Little Lost Robot» (1947), novelette

- «Escape!» (1945)

- «Evidence» (1946), novelette

- «The Evitable Conflict» (1950), novelette

Reception[edit]

The New York Times described I, Robot as «an exciting science thriller [which] could be fun for those whose nerves are not already made raw by the potentialities of the atomic age».[2]

Describing it as «continuously fascinating», Groff Conklin «unreservedly recommended» the book.[3]

P. Schuyler Miller recommended the collection: «For puzzle situations, for humor, for warm character, [and] for most of the values of plain good writing.»[4]

Dramatic adaptations[edit]

Television[edit]

At least three of the short stories from I, Robot have been adapted for television. The first was a 1962 episode of Out of this World hosted by Boris Karloff called «Little Lost Robot» with Maxine Audley as Susan Calvin. Two short stories from the collection were made into episodes of Out of the Unknown: «The Prophet» (1967), based on «Reason»; and «Liar!» (1969). Both episodes were wiped by the BBC and are no longer thought to exist, although video clips, audio extracts and still photographs have survived.[5] The 12th episode of the USSR science fiction TV series This Fantastic World, filmed in 1987 and entitled Don’t Joke with Robots, was based on works by Aleksandr Belyaev and Fredrik Kilander as well as Asimov’s «Liar!» story.[6]

Both the original and revival series of The Outer Limits include episodes named «I, Robot»; however, both are adaptations of the Earl and Otto Binder story of that name and are unconnected with Asimov’s work.

Films[edit]

Harlan Ellison’s screenplay (1978)[edit]

In the late 1970s, Warner Bros. acquired the option to make a film based on the book, but no screenplay was ever accepted. The most notable attempt was one by Harlan Ellison, who collaborated with Asimov himself to create a version which captured the spirit of the original. Asimov is quoted as saying that this screenplay would lead to «the first really adult, complex, worthwhile science fiction movie ever made.»

Ellison’s script builds a framework around Asimov’s short stories that involves a reporter named Robert Bratenahl tracking down information about Susan Calvin’s alleged former lover Stephen Byerly. Asimov’s stories are presented as flashbacks that differ from the originals in their stronger emphasis on Calvin’s character. Ellison placed Calvin into stories in which she did not originally appear and fleshed out her character’s role in ones where she did. In constructing the script as a series of flashbacks that focused on character development rather than action, Ellison used the film Citizen Kane as a model.[7]

Although acclaimed by critics, the screenplay is generally considered to have been unfilmable based upon the technology and average film budgets of the time.[7] Asimov also believed that the film may have been scrapped because of a conflict between Ellison and the producers: when the producers suggested changes in the script, instead of being diplomatic as advised by Asimov, Ellison «reacted violently» and offended the producers.[8] The script was serialized in Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine in late 1987, and eventually appeared in book form under the title I, Robot: The Illustrated Screenplay, in 1994 (reprinted 2004, ISBN 1-4165-0600-4).

2004 film[edit]

The film I, Robot, starring Will Smith, was released by Twentieth Century Fox on July 16, 2004 in the United States. Its plot incorporates elements of «Little Lost Robot»,[9] some of Asimov’s character names and the Three Laws. However, the plot of the movie is mostly original work adapted from the screenplay Hardwired by Jeff Vintar, completely unlinked to Asimov’s stories[9] and has been compared to Asimov’s The Caves of Steel, which revolves around the murder of a roboticist (although the rest of the film’s plot is not based on that novel or other works by Asimov). Unlike the books by Asimov, the movie featured hordes of killer robots.

Radio[edit]

BBC Radio 4 aired an audio drama adaptation of five of the I, Robot stories on their 15 Minute Drama in 2017, dramatized by Richard Kurti and starring Hermione Norris.

- Robbie[10]

- Reason[11]

- Little Lost Robot[12]

- Liar[13]

- The Evitable Conflict[14]

These also aired in a single program on BBC Radio 4 Extra as Isaac Asimov’s ‘I, Robot’: Omnibus.[15]

Prequels[edit]

The Asimov estate asked Mickey Zucker Reichert (best known for the Norse fantasy Renshai series) to write three[16] prequels for I, Robot, since she was a science fiction writer with a medical degree who had first met Asimov when she was 23, although she did not know him well.[17] She was the first female writer to be authorized to write stories based on Asimov’s novels.[17]

The follow-ups to Asimov’s Foundation series had been written by Gregory Benford, Greg Bear, and David Brin.[16]

Berkley Books ordered the I, Robot prequels, which included:

- I, Robot: To Protect (2011)

- I, Robot: To Obey (2013)

- I, Robot: To Preserve (2016)

Popular culture references[edit]

In 2004, The Saturday Evening Post said that I, Robot’s Three Laws «revolutionized the science fiction genre and made robots far more interesting than they ever had been before.»[18] I, Robot has influenced many aspects of modern popular culture, particularly with respect to science fiction and technology. One example of this is in the technology industry. The name of the real-life modem manufacturer named U.S. Robotics was directly inspired by I, Robot. The name is taken from the name of a robot manufacturer («United States Robots and Mechanical Men») that appears throughout Asimov’s robot short stories.[19]

Many works in the field of science fiction have also paid homage to Asimov’s collection.[citation needed]

An episode of the original Star Trek series, «I, Mudd» (1967), which depicts a planet of androids in need of humans, references I, Robot. Another reference appears in the title of a Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, «I, Borg» (1992), in which Geordi La Forge befriends a lost member of the Borg collective and teaches it a sense of individuality and free will.[citation needed]

A Doctor Who story, The Robots of Death (1977), references I, Robot with the «First Principle», stating: «It is forbidden for robots to harm humans.»[citation needed]

In the film Aliens (1986), the synthetic person Bishop paraphrases Asimov’s First Law in the line: «It is impossible for me to harm, or by omission of action allow to be harmed, a human being.»[citation needed]

An episode of The Simpsons entitled «I D’oh Bot» (2004) has Professor Frink build a robot named «Smashius Clay» (also named «Killhammad Aieee») that follows all three of Asimov’s laws of robotics.[citation needed]

The animated science fiction/comedy Futurama makes several references to I, Robot. The title of the episode «I, Roommate» (1999) is a spoof on I, Robot although the plot of the episode has little to do with the original stories.[20] Additionally, the episode «The Cyber House Rules» included an optician named «Eye Robot» and the episode «Anthology of Interest II» included a segment called «I, Meatbag.»[citation needed] Also in «Bender’s Game» (2008) the psychiatrist is shown a logical fallacy and explodes when the assistant shouts «Liar!» a la «Liar!». Leela once told Bender to «cover his ears» so that he would not hear the robot-destroying paradox which she used to destroy Robot Santa (he punishes the bad, he kills people, killing is bad, therefore he must punish himself), causing a total breakdown; additionally, Bender has stated that he is Three Laws Safe.[citation needed]

The positronic brain, which Asimov named his robots’ central processors, is what powers Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation, as well as other Soong type androids. Positronic brains have been referenced in a number of other television shows including Doctor Who, Once Upon a Time… Space, Perry Rhodan, The Number of the Beast, and others.[citation needed]

Author Cory Doctorow has written a story called «I, Robot» as homage to and critique of Asimov,[21] as well as «I, Row-Boat», both released in the 2007 short story collection Overclocked: Stories of the Future Present. He has also said, «If I return to this theme, it will be with a story about uplifted cheese sandwiches, called ‘I, Rarebit.'»[22]

Other cultural references to the book are less directly related to science fiction and technology. The album I Robot (1977), by The Alan Parsons Project, was inspired by Asimov’s I, Robot. In its original conception, the album was to follow the themes and concepts presented in the short story collection. The Alan Parsons Project were not able to obtain the rights in spite of Asimov’s enthusiasm; he had already assigned the rights elsewhere. Thus, the album’s concept was altered slightly although the name was kept (minus comma to avoid copyright infringement).[23] An album, I, Human (2009), by Singaporean band Deus Ex Machina, draws heavily upon Asimov’s principles on robotics and applies it to the concept of cloning.[24]

The Indian science fiction film Endhiran (2010) refers to Asimov’s three laws for artificial intelligence for the fictional character «Chitti: The Robot». When a scientist takes in the robot for evaluation, the panel inquires whether the robot was built using the Three Laws of Robotics.[citation needed]

The theme for Burning Man 2018 was «I, Robot».[25]

See also[edit]

- I, Robot (film)

Citations[edit]

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1979). Isaac Asimov Presents the Great SF Stories.

- ^ «Realm of the Spacemen». The New York Times Book Review. February 4, 1951.

- ^ Conklin, Groff (April 1951). «Galaxy’s 5 Star Shelf». Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 59–61.

- ^ Book Reviews. Astounding Science Fiction. September 1951. pp. 124–125.

- ^ «IMDb list of actresses that have played Susan Calvin».

- ^ (in Russian) State Fund of Television and Radio Programs Archived September 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Weil, Ellen; Wolfe, Gary K. (2002). Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-8142-0892-4.

- ^ Isaac Asimov, «Hollywood and I». In Asimov’s Science Fiction, May 1979.

- ^ a b Topel, Fred (August 17, 2004). ««Jeff Vintar was Hardwired for I, ROBOT» (interview with Jeff Vintar, script writer)». Screenwriter’s Utopia. Christopher Wehner. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ «Robbie, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «Reason, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «Little Lost Robot, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «Liar, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «The Evitable Conflict, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «Isaac Asimov’s ‘I, Robot’: Omnibus — BBC Radio 4 Extra». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ a b «Fantasy author to write new ‘Isaac Asimov’ novels». October 29, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ a b «Area author continues works of Isaac Asimov». Kalona News. May 25, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ Kreiter, Ted. «Revisiting The Master Of Science Fiction». Saturday Evening Post. 276 (6): 38. ISSN 0048-9239.

- ^ U.S. Robotics Press Kit, 2004, p3 PDF format Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ M. Keith Booker (2006). Drawn to Television: Prime-Time Animation from the Flintstones to Family Guy. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 122. ISBN 0-275-99019-2.

- ^ Doctorow, Cory. «Cory Doctorow’s Craphound.com». http://www.craphound.com/?p=189 (retrieved April 27, 2008)

- ^ Doctorow, Cory. «Cory Doctorow’s Craphound.com». Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Official Alan Parsons Project website Archived 2009-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Reviews». Live 4 Metal. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ «I, ROBOT».

General and cited references[edit]

- Chalker, Jack L.; Mark Owings (1998). The Science-Fantasy Publishers: A Bibliographic History, 1923–1998. Westminster, MD and Baltimore: Mirage Press, Ltd. p. 299.

External links[edit]

- I, Robot title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- I, Robot at Open Library

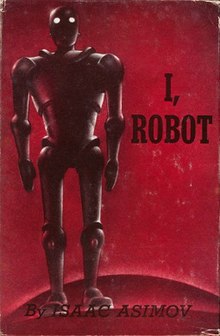

First edition cover |

|

| Author | Isaac Asimov |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Edd Cartier |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Robot series |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Gnome Press |

|

Publication date |

December 2, 1950 |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 253 |

| Followed by | The Complete Robot |

I, Robot is a fixup (compilation) novel of science fiction short stories or essays by American writer Isaac Asimov. The stories originally appeared in the American magazines Super Science Stories and Astounding Science Fiction between 1940 and 1950 and were then compiled into a book for stand-alone (single issue / special edition) publication by Gnome Press in 1950, in an initial edition of 5,000 copies. The stories are woven together by a framing narrative in which the fictional Dr. Susan Calvin tells each story to a reporter (who serves as the narrator) in the 21st century. Although the stories can be read separately, they share a theme of the interaction of humans, robots, and morality, and when combined they tell a larger story of Asimov’s fictional history of robotics.[citation needed]

Several of the stories feature the character of Dr. Calvin, chief robopsychologist at U.S. Robots and Mechanical Men, Inc., the major manufacturer of robots. Upon their publication in this collection, Asimov wrote a framing sequence presenting the stories as Calvin’s reminiscences during an interview with her about her life’s work, chiefly concerned with aberrant behaviour of robots and the use of «robopsychology» to sort out what is happening in their positronic brain. The book also contains the short story in which Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics first appear, which had large influence on later science fiction and had impact on thought on ethics of artificial intelligence as well. Other characters that appear in these short stories are Powell and Donovan, a field-testing team which locates flaws in USRMM’s prototype models.[citation needed]

The collection shares a title with the then recent short story «I, Robot» (1939) by Eando Binder (pseudonym of Earl and Otto Binder), which greatly influenced Asimov. Asimov had wanted to call his collection Mind and Iron and objected when the publisher made the title the same as Binder’s. In his introduction to the story in Isaac Asimov Presents the Great SF Stories (1979), Asimov wrote:

It certainly caught my attention. Two months after I read it, I began «Robbie», about a sympathetic robot, and that was the start of my positronic robot series. Eleven years later, when nine of my robot stories were collected into a book, the publisher named the collection I, Robot over my objections. My book is now the more famous, but Otto’s story was there first.

— Isaac Asimov (1979)[1]

Contents[edit]

- «Introduction» (the initial portion of the framing story or linking text)

- «Robbie» (1940, 1950)

- «Runaround» (1942), novelette

- «Reason» (1941)

- «Catch That Rabbit» (1944)

- «Liar!» (1941)

- «Little Lost Robot» (1947), novelette

- «Escape!» (1945)

- «Evidence» (1946), novelette

- «The Evitable Conflict» (1950), novelette

Reception[edit]

The New York Times described I, Robot as «an exciting science thriller [which] could be fun for those whose nerves are not already made raw by the potentialities of the atomic age».[2]

Describing it as «continuously fascinating», Groff Conklin «unreservedly recommended» the book.[3]

P. Schuyler Miller recommended the collection: «For puzzle situations, for humor, for warm character, [and] for most of the values of plain good writing.»[4]

Dramatic adaptations[edit]

Television[edit]

At least three of the short stories from I, Robot have been adapted for television. The first was a 1962 episode of Out of this World hosted by Boris Karloff called «Little Lost Robot» with Maxine Audley as Susan Calvin. Two short stories from the collection were made into episodes of Out of the Unknown: «The Prophet» (1967), based on «Reason»; and «Liar!» (1969). Both episodes were wiped by the BBC and are no longer thought to exist, although video clips, audio extracts and still photographs have survived.[5] The 12th episode of the USSR science fiction TV series This Fantastic World, filmed in 1987 and entitled Don’t Joke with Robots, was based on works by Aleksandr Belyaev and Fredrik Kilander as well as Asimov’s «Liar!» story.[6]

Both the original and revival series of The Outer Limits include episodes named «I, Robot»; however, both are adaptations of the Earl and Otto Binder story of that name and are unconnected with Asimov’s work.

Films[edit]

Harlan Ellison’s screenplay (1978)[edit]

In the late 1970s, Warner Bros. acquired the option to make a film based on the book, but no screenplay was ever accepted. The most notable attempt was one by Harlan Ellison, who collaborated with Asimov himself to create a version which captured the spirit of the original. Asimov is quoted as saying that this screenplay would lead to «the first really adult, complex, worthwhile science fiction movie ever made.»

Ellison’s script builds a framework around Asimov’s short stories that involves a reporter named Robert Bratenahl tracking down information about Susan Calvin’s alleged former lover Stephen Byerly. Asimov’s stories are presented as flashbacks that differ from the originals in their stronger emphasis on Calvin’s character. Ellison placed Calvin into stories in which she did not originally appear and fleshed out her character’s role in ones where she did. In constructing the script as a series of flashbacks that focused on character development rather than action, Ellison used the film Citizen Kane as a model.[7]

Although acclaimed by critics, the screenplay is generally considered to have been unfilmable based upon the technology and average film budgets of the time.[7] Asimov also believed that the film may have been scrapped because of a conflict between Ellison and the producers: when the producers suggested changes in the script, instead of being diplomatic as advised by Asimov, Ellison «reacted violently» and offended the producers.[8] The script was serialized in Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine in late 1987, and eventually appeared in book form under the title I, Robot: The Illustrated Screenplay, in 1994 (reprinted 2004, ISBN 1-4165-0600-4).

2004 film[edit]

The film I, Robot, starring Will Smith, was released by Twentieth Century Fox on July 16, 2004 in the United States. Its plot incorporates elements of «Little Lost Robot»,[9] some of Asimov’s character names and the Three Laws. However, the plot of the movie is mostly original work adapted from the screenplay Hardwired by Jeff Vintar, completely unlinked to Asimov’s stories[9] and has been compared to Asimov’s The Caves of Steel, which revolves around the murder of a roboticist (although the rest of the film’s plot is not based on that novel or other works by Asimov). Unlike the books by Asimov, the movie featured hordes of killer robots.

Radio[edit]

BBC Radio 4 aired an audio drama adaptation of five of the I, Robot stories on their 15 Minute Drama in 2017, dramatized by Richard Kurti and starring Hermione Norris.

- Robbie[10]

- Reason[11]

- Little Lost Robot[12]

- Liar[13]

- The Evitable Conflict[14]

These also aired in a single program on BBC Radio 4 Extra as Isaac Asimov’s ‘I, Robot’: Omnibus.[15]

Prequels[edit]

The Asimov estate asked Mickey Zucker Reichert (best known for the Norse fantasy Renshai series) to write three[16] prequels for I, Robot, since she was a science fiction writer with a medical degree who had first met Asimov when she was 23, although she did not know him well.[17] She was the first female writer to be authorized to write stories based on Asimov’s novels.[17]

The follow-ups to Asimov’s Foundation series had been written by Gregory Benford, Greg Bear, and David Brin.[16]

Berkley Books ordered the I, Robot prequels, which included:

- I, Robot: To Protect (2011)

- I, Robot: To Obey (2013)

- I, Robot: To Preserve (2016)

Popular culture references[edit]

In 2004, The Saturday Evening Post said that I, Robot’s Three Laws «revolutionized the science fiction genre and made robots far more interesting than they ever had been before.»[18] I, Robot has influenced many aspects of modern popular culture, particularly with respect to science fiction and technology. One example of this is in the technology industry. The name of the real-life modem manufacturer named U.S. Robotics was directly inspired by I, Robot. The name is taken from the name of a robot manufacturer («United States Robots and Mechanical Men») that appears throughout Asimov’s robot short stories.[19]

Many works in the field of science fiction have also paid homage to Asimov’s collection.[citation needed]

An episode of the original Star Trek series, «I, Mudd» (1967), which depicts a planet of androids in need of humans, references I, Robot. Another reference appears in the title of a Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, «I, Borg» (1992), in which Geordi La Forge befriends a lost member of the Borg collective and teaches it a sense of individuality and free will.[citation needed]

A Doctor Who story, The Robots of Death (1977), references I, Robot with the «First Principle», stating: «It is forbidden for robots to harm humans.»[citation needed]

In the film Aliens (1986), the synthetic person Bishop paraphrases Asimov’s First Law in the line: «It is impossible for me to harm, or by omission of action allow to be harmed, a human being.»[citation needed]

An episode of The Simpsons entitled «I D’oh Bot» (2004) has Professor Frink build a robot named «Smashius Clay» (also named «Killhammad Aieee») that follows all three of Asimov’s laws of robotics.[citation needed]

The animated science fiction/comedy Futurama makes several references to I, Robot. The title of the episode «I, Roommate» (1999) is a spoof on I, Robot although the plot of the episode has little to do with the original stories.[20] Additionally, the episode «The Cyber House Rules» included an optician named «Eye Robot» and the episode «Anthology of Interest II» included a segment called «I, Meatbag.»[citation needed] Also in «Bender’s Game» (2008) the psychiatrist is shown a logical fallacy and explodes when the assistant shouts «Liar!» a la «Liar!». Leela once told Bender to «cover his ears» so that he would not hear the robot-destroying paradox which she used to destroy Robot Santa (he punishes the bad, he kills people, killing is bad, therefore he must punish himself), causing a total breakdown; additionally, Bender has stated that he is Three Laws Safe.[citation needed]

The positronic brain, which Asimov named his robots’ central processors, is what powers Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation, as well as other Soong type androids. Positronic brains have been referenced in a number of other television shows including Doctor Who, Once Upon a Time… Space, Perry Rhodan, The Number of the Beast, and others.[citation needed]

Author Cory Doctorow has written a story called «I, Robot» as homage to and critique of Asimov,[21] as well as «I, Row-Boat», both released in the 2007 short story collection Overclocked: Stories of the Future Present. He has also said, «If I return to this theme, it will be with a story about uplifted cheese sandwiches, called ‘I, Rarebit.'»[22]

Other cultural references to the book are less directly related to science fiction and technology. The album I Robot (1977), by The Alan Parsons Project, was inspired by Asimov’s I, Robot. In its original conception, the album was to follow the themes and concepts presented in the short story collection. The Alan Parsons Project were not able to obtain the rights in spite of Asimov’s enthusiasm; he had already assigned the rights elsewhere. Thus, the album’s concept was altered slightly although the name was kept (minus comma to avoid copyright infringement).[23] An album, I, Human (2009), by Singaporean band Deus Ex Machina, draws heavily upon Asimov’s principles on robotics and applies it to the concept of cloning.[24]

The Indian science fiction film Endhiran (2010) refers to Asimov’s three laws for artificial intelligence for the fictional character «Chitti: The Robot». When a scientist takes in the robot for evaluation, the panel inquires whether the robot was built using the Three Laws of Robotics.[citation needed]

The theme for Burning Man 2018 was «I, Robot».[25]

See also[edit]

- I, Robot (film)

Citations[edit]

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1979). Isaac Asimov Presents the Great SF Stories.

- ^ «Realm of the Spacemen». The New York Times Book Review. February 4, 1951.

- ^ Conklin, Groff (April 1951). «Galaxy’s 5 Star Shelf». Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 59–61.

- ^ Book Reviews. Astounding Science Fiction. September 1951. pp. 124–125.

- ^ «IMDb list of actresses that have played Susan Calvin».

- ^ (in Russian) State Fund of Television and Radio Programs Archived September 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Weil, Ellen; Wolfe, Gary K. (2002). Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-8142-0892-4.

- ^ Isaac Asimov, «Hollywood and I». In Asimov’s Science Fiction, May 1979.

- ^ a b Topel, Fred (August 17, 2004). ««Jeff Vintar was Hardwired for I, ROBOT» (interview with Jeff Vintar, script writer)». Screenwriter’s Utopia. Christopher Wehner. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ «Robbie, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «Reason, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «Little Lost Robot, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «Liar, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «The Evitable Conflict, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama — BBC Radio 4». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ «Isaac Asimov’s ‘I, Robot’: Omnibus — BBC Radio 4 Extra». BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ a b «Fantasy author to write new ‘Isaac Asimov’ novels». October 29, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ a b «Area author continues works of Isaac Asimov». Kalona News. May 25, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ Kreiter, Ted. «Revisiting The Master Of Science Fiction». Saturday Evening Post. 276 (6): 38. ISSN 0048-9239.

- ^ U.S. Robotics Press Kit, 2004, p3 PDF format Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ M. Keith Booker (2006). Drawn to Television: Prime-Time Animation from the Flintstones to Family Guy. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 122. ISBN 0-275-99019-2.

- ^ Doctorow, Cory. «Cory Doctorow’s Craphound.com». http://www.craphound.com/?p=189 (retrieved April 27, 2008)

- ^ Doctorow, Cory. «Cory Doctorow’s Craphound.com». Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Official Alan Parsons Project website Archived 2009-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Reviews». Live 4 Metal. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ «I, ROBOT».

General and cited references[edit]

- Chalker, Jack L.; Mark Owings (1998). The Science-Fantasy Publishers: A Bibliographic History, 1923–1998. Westminster, MD and Baltimore: Mirage Press, Ltd. p. 299.

External links[edit]

- I, Robot title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- I, Robot at Open Library

- Главная

- Книги

- Я, робот

Назад

4 обложки

1950 г.

Автор: Айзек Азимов

Номер Азимова: 2

Вселенная Айзека Азимова

Действие романа происходит в том же мире, что и действие многих других книг Азимова, в частности, рассказов о роботах и цикла об империи Трантора; таким образом, они объединяются в своеобразную историю будущего.

2-я книга в общей истории

Подробнее

«Я, робот» – сборник научно-фантастических рассказов (впервые опубликован в 1950), давно ставших для любителей фантастики классикой жанра и оказавших большое влияние на современную научно-фантастическую литературу. В данном сборнике впервые были сформулированы Три закона робототехники.

Нравится книга? Посоветуй её друзьям:

Я, робот

2004 г.

Слушайте онлайн бесплатно

Исполнитель аудиокниги: Вадим Максимов

Переводчик: Алексей Иорданский

Продолжительность: 8 часов

Я, робот

I, robot

- Год

- 2004

- Страна

- США, Германия

- Режиссер

- Алекс Пройас

- Бюджет

- $120 000 000

- Сборы в мире

- $347 234 916

- Оценка kinopoisk.ru

- ≈ 7.835 ≈ 150 461

- Оценка IMDb

- ≈ 7.10 405 714

Этот фильм не был сделан по какому-либо конкретному произведению. Он снят именно «по мотивам» и скорее вдохновлён рассказами Азимова. Действие происходит в одной вселенной, и в фильме встречаются герои книг, но есть некоторые серьезные расхождения с оригиналом.

Действие картины происходит в 2035 году, когда роботы стали непременным атрибутом жизни человека. Протагонист — детектив, скептически относящийся к роботам, расследует убийство, в котором был замешан один из них. Неужели был нарушен один из самых важных законов робототехники — робот никогда не поднимет руки на человека. Это и предстоит выяснить главному герою.

Подробнее

Содержание сборника

-

Робби

(Robbie)

1940 г -

Логика

(Reason)

1941 г -

Лжец!

(Liar!)

1941 г -

Хоровод

(Runaround)

1942 г -

Как поймать кролика

(Catch that Rabbit)

1944 г -

Выход из положения

(Escape!)

1945 г -

Улики

(Evidence)

1946 г -

Как потерялся робот

(Little lost robot)

1947 г -

Разрешимое противоречие

(The Evitable conflict)

1950 г -

Предисловие от лица Сьюзен Кэлвин

(Introduction)

1950 г

Входит в серию

Арты 12 артов

Случайные цитаты из книги —

64 цитаты

Фанфики

Калибан

Роджер Макбрайд Аллен (Roger MacBride Allen)

Небольшую планету Инферно сотрясают масштабные проблемы — надвигающаяся климатическая катастрофа, национально-культурный конфликт, медленное разложение социума. А в центре кризиса — покушение на жизнь лучшего специалиста в сфере робототехники. Под подозрением — экспериментальный робот, одним своим существованием грозящий остаткам мира и спокойствия.

Год: 1993

Инферно

Роджер Макбрайд Аллен (Roger MacBride Allen)

Зверское убийство Правителя Грега приводит планету Инферно на грань междоусобной войны. И без того напряженные отношения между колонистами, тысячелетия назад заселившими эту землю, и вновь прибывшими поселенцами грозят перерасти в откровенную бойню. Шериф Альвар Крэш делает все, чтобы найти преступника и предотвратить резню, но дело кажется безнадежным. Пока у следствия только дыра от бластера в груди Правителя, полсотни искореженных роботов охраны, дюжина подозреваемых, вроде бы имевших «мотив», и никаких реальных зацепок.

Год: 1994

Валгалла

Роджер Макбрайд Аллен (Roger MacBride Allen)

Экологическая катастрофа грозит смертью или изгнанием жителям планеты Инферно. Единственный способ спасения, предложенный ученым Давло Лентраллом, очень опасен и не гарантирует успеха. Более того, в результате утечки информации в игру против Правителя Крэша, готового рискнуть во имя будущего, вступают те, кому план не по душе. Им удается добиться, что роботы перестают следовать постулатам «Трех законов роботехники» и вместо того, чтобы быть верными слугами и помощниками людей, становятся их главными противниками в борьбе за выживание.

Год: 1996

Mirage

Марк Тидеман (Mark W Tiedemann)

На конференции, объединяющей космонавтов, поселенцев и представителей Земли, сенатор Земли и старший космический посол Авроры выступают за восстановление позитронных роботов на Земле, отвергая годы страха и обиды. Это опасная позиция.

Год: 2000

Chimera

Марк Тидеман (Mark W Tiedemann)

Корен Ланра является главой службы безопасности Dynan Manuel Industries. Говорили, что он никогда не заботился о бюрократии, пиратстве или обмане. И он ненавидит тайны. Проблемы Ланры начинаются со смерти Нирона Лумса, дочери президента Dynan Manuel Industries, во время злополучной миссии по контрабанде незаконных иммигрантов с Земли в колонию Nova Levis — все были убиты, но почему?

Год: 2001

Aurora

Марк Тидеман (Mark W Tiedemann)

В двух предыдущих книгах автор исследовал страх и ненависть к роботам и их владельцам. В этой книге главные герои пытаются разоблачить вдохновителя, ответственного за убийства, террористические атаки и попытки лишить их жизни.

Год: 2002

Have Robot, Will Travel

Александр Ирвин (Alexander C Irvine)

Дерек и Ариэль попали в совершенно новое приключение. Человек был убит, и все подсказки указывают на то, что убийца — робот. Но как такое возможно, ведь роботы запрограммированы так, чтобы никогда не наносить вред людям? Дерек и Ариэль должны найти убийцу — прежде, чем они станут очередными жертвами…

Год: 2004

Другие книги в этом жанре

Все грехи мира

All the Troubles of the World

Жанр: научно-фантастический сборник рассказов

Год: 1989

Нравится книга? Посоветуйте её друзьям: