|

Veliky Novgorod Великий Новгород |

|

|---|---|

|

City[1] |

|

Counter-clockwise from top right: the Millennium of Russia, cathedral of St. Sophia, the fine arts museum, St. George’s Monastery, the Kremlin, Yaroslav’s Court |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: none[3] | |

|

Location of Veliky Novgorod |

|

|

Veliky Novgorod Location of Veliky Novgorod Veliky Novgorod Veliky Novgorod (European Russia) Veliky Novgorod Veliky Novgorod (Europe) |

|

| Coordinates: 58°33′N 31°16′E / 58.550°N 31.267°ECoordinates: 58°33′N 31°16′E / 58.550°N 31.267°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Novgorod Oblast[2] |

| First mentioned | 859[4] |

| Government | |

| • Body | Duma[5] |

| • Mayor (Head)[5] | Aleksandr Rozbaum |

| Area

[6] |

|

| • Total | 90 km2 (30 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 25 m (82 ft) |

| Population

(2010 Census)[7] |

|

| • Total | 218,717 |

| • Estimate

(2018)[8] |

222,868 (+1.9%) |

| • Rank | 85th in 2010 |

| • Density | 2,400/km2 (6,300/sq mi) |

|

Administrative status |

|

| • Subordinated to | city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod[2] |

| • Capital of | Novgorod Oblast[2], city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod[2] |

|

Municipal status |

|

| • Urban okrug | Veliky Novgorod Urban Okrug[9] |

| • Capital of | Veliky Novgorod Urban Okrug[9], Novgorodsky Municipal District[9] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| Postal code(s)[11] |

173000–173005, 173007–173009, 173011–173016, 173018, 173020–173025, 173700, 173899, 173920, 173955, 173990, 173999 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 8162 |

| OKTMO ID | 49701000001 |

| Website | www.adm.nov.ru |

Veliky Novgorod (Russian: Великий Новгород, IPA: [vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət], lit. ‘Great Newtown’), also known as just Novgorod (Новгород), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the oldest cities in Russia,[12] being first mentioned in the 9th century. The city lies along the Volkhov River just downstream from its outflow from Lake Ilmen and is situated on the M10 federal highway connecting Moscow and Saint Petersburg. UNESCO recognized Novgorod as a World Heritage Site in 1992. The city has a population of 224,286 (2021 Census).[13]

At its peak during the 14th century, the city was the capital of the Novgorod Republic and was one of Europe’s largest cities.[14] The «Veliky» («great») part was added to the city’s name in 1999.

History[edit]

Early developments[edit]

The Sofia First Chronicle makes initial mention of it in 859, while the Novgorod First Chronicle first mentions it in 862, when it was purportedly already a major Baltics-to-Byzantium station on the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks.[15] The Charter of Veliky Novgorod recognizes 859 as the year when the city was first mentioned.[4] Novgorod is traditionally considered to be a cradle of Russian statehood.[16]

The oldest archaeological excavations in the middle to late 20th century, however, have found cultural layers dating back to the late 10th century, the time of the Christianization of Rus’ and a century after it was allegedly founded.[17] Archaeological dating is fairly easy and accurate to within 15–25 years, as the streets were paved with wood, and most of the houses made of wood, allowing tree ring dating.

The Varangian name of the city Holmgård or Holmgard (Holmgarðr or Holmgarðir) is mentioned in Norse Sagas as existing at a yet earlier stage, but the correlation of this reference with the actual city is uncertain.[18] Originally, Holmgård referred to the stronghold, now only 2 km (1.2 miles) to the south of the center of the present-day city, Rurikovo Gorodische (named in comparatively modern times after the Varangian chieftain Rurik, who supposedly made it his «capital» around 860). Archaeological data suggests that the Gorodishche, the residence of the Knyaz (prince), dates from the mid-9th century,[19] whereas the town itself dates only from the end of the 10th century; hence the name Novgorod, «new city», from Old East Slavic Новъ and Городъ (Nov and Gorod); the Old Norse term Nýgarðr is a calque of an Old Russian word. First mention of this Norse etymology to the name of the city of Novgorod (and that of other cities within the territory of the then Kievan Rus’) occurs in the 10th-century policy manual De Administrando Imperio by Byzantine emperor Constantine VII.

Princely state within Kievan Rus’[edit]

In 882, Rurik’s successor, Oleg of Novgorod, conquered Kiev and founded the state of Kievan Rus’. Novgorod’s size as well as its political, economic, and cultural influence made it the second most important city in Kievan Rus’. According to a custom, the elder son and heir of the ruling Kievan monarch was sent to rule Novgorod even as a minor. When the ruling monarch had no such son, Novgorod was governed by posadniks, such as the legendary Gostomysl, Dobrynya, Konstantin, and Ostromir.

Of all their princes, Novgorodians most cherished the memory of Yaroslav the Wise, who sat as Prince of Novgorod from 1010 to 1019, while his father, Vladimir the Great, was a prince in Kiev. Yaroslav promulgated the first written code of laws (later incorporated into Russkaya Pravda) among the Eastern Slavs and is said to have granted the city a number of freedoms or privileges, which they often referred to in later centuries as precedents in their relations with other princes. His son, Vladimir, sponsored construction of the great St. Sophia Cathedral, more accurately translated as the Cathedral of Holy Wisdom, which stands to this day.

Early foreign ties[edit]

In Norse sagas the city is mentioned as the capital of Gardariki.[20] Many Viking kings and yarls came to Novgorod seeking refuge or employment, including Olaf I of Norway, Olaf II of Norway, Magnus I of Norway, and Harald Hardrada.[21] No more than a few decades after the 1030 death and subsequent canonization of Olaf II of Norway, the city’s community had erected in his memory Saint Olaf’s Church in Novgorod.

The Gotland town of Visby functioned as the leading trading center in the Baltic before the Hansa League. At Novgorod in 1080, Visby merchants established a trading post which they named Gutagard (also known as Gotenhof).[22] Later, in the first half of the 13th century, merchants from northern Germany also established their own trading station in Novgorod, known as Peterhof.[23] At about the same time, in 1229, German merchants at Novgorod were granted certain privileges, which made their position more secure.[24]

Novgorod Republic[edit]

In 1136, the Novgorodians dismissed their prince Vsevolod Mstislavich. The year is seen as the traditional beginning of the Novgorod Republic. The city was able to invite and dismiss a number of princes over the next two centuries, but the princely office was never abolished and powerful princes, such as Alexander Nevsky, could assert their will in the city regardless of what Novgorodians said.[25] The city state controlled most of Europe’s northeast, from lands east of today’s Estonia to the Ural Mountains, making it one of the largest states in medieval Europe, although much of the territory north and east of Lakes Ladoga and Onega was sparsely populated and never organized politically.

One of the most important local figures in Novgorod was the posadnik, or mayor, an official elected by the public assembly (called the Veche) from among the city’s boyars, or aristocracy. The tysyatsky, or «thousandman», originally the head of the town militia but later a commercial and judicial official, was also elected by the Veche. Another important local official was the Archbishop of Novgorod who shared power with the boyars.[26] Archbishops were elected by the Veche or by the drawing of lots, and after their election, were sent to the metropolitan for consecration.[27]

While a basic outline of the various officials and the Veche can be drawn up, the city-state’s exact political constitution remains unknown. The boyars and the archbishop ruled the city together, although where one official’s power ended and another’s began is uncertain. The prince, although his power was reduced from around the middle of the 12th century, was represented by his namestnik, or lieutenant, and still played important roles as a military commander, legislator and jurist. The exact composition of the Veche, too, is uncertain, with some historians, such as Vasily Klyuchevsky, claiming it was democratic in nature, while later scholars, such as Marxists Valentin Ianin and Aleksandr Khoroshev, see it as a «sham democracy» controlled by the ruling elite.

In the 13th century, Novgorod, while not a member of the Hanseatic League, was the easternmost kontor, or entrepôt, of the league, being the source of enormous quantities of luxury (sable, ermine, fox, marmot) and non-luxury furs (squirrel pelts).[28]

Throughout the Middle Ages, the city thrived culturally. A large number of birch bark letters have been unearthed in excavations, perhaps suggesting widespread literacy. It was in Novgorod that the Novgorod Codex, the oldest Slavic book written north of Bulgaria, and the oldest inscription in a Finnic language (Birch bark letter no. 292) were unearthed. Some of the most ancient Russian chronicles (Novgorod First Chronicle) were written in the scriptorium of the archbishops who also promoted iconography and patronized church construction. The Novgorod merchant Sadko became a popular hero of Russian folklore.

Novgorod was never conquered by the Mongols during the Mongol invasion of Rus. The Mongol army turned back about 200 kilometers (120 mi) from the city, not because of the city’s strength, but probably because the Mongol commanders did not want to get bogged down in the marshlands surrounding the city. However, the grand princes of Moscow, who acted as tax collectors for the khans of the Golden Horde, did collect tribute in Novgorod, most notably Yury Danilovich and his brother, Ivan Kalita.

The 16th century Vision of Tarasius icon depicts Novgorod with the Sofia side to the left and the Commercial side to the right. The inhabitants of the city are shown doing their day-to-day work while being guarded by the angels

In 1259, Mongol tax-collectors and census-takers arrived in the city, leading to political disturbances and forcing Alexander Nevsky to punish a number of town officials (he cut off their noses) for defying him as Grand Prince of Vladimir (soon to be the khan’s tax-collector in Russia) and his Mongol overlords. In the 14th century, raids by Novgorod pirates, or ushkuiniki,[29] sowed fear as far as Kazan and Astrakhan, assisting Novgorod in wars with the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

During the era of Old Rus’ State, Novgorod was a trade hub at the northern end of both the Volga trade route and the «route from the Varangians to the Greeks» along the Dnieper river system. A vast array of goods were transported along these routes and exchanged with local Novgorod merchants and other traders. The farmers of Gotland retained the Saint Olof trading house well into the 12th century. Later German merchantmen also established tradinghouses in Novgorod. Scandinavian royalty would intermarry with Russian princes and princesses.

After the great schism, Novgorod struggled from the beginning of the 13th century against Swedish, Danish, and German crusaders. During the Swedish-Novgorodian Wars, the Swedes invaded lands where some of the population had earlier paid tribute to Novgorod. The Germans had been trying to conquer the Baltic region since the late 12th century. Novgorod went to war 26 times with Sweden and 11 times with the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. The German knights, along with Danish and Swedish feudal lords, launched a series of uncoordinated attacks in 1240–1242. Novgorodian sources mention that a Swedish army was defeated in the Battle of the Neva in 1240. The Baltic German campaigns ended in failure after the Battle on the Ice in 1242. After the foundation of the castle of Viborg in 1293 the Swedes gained a foothold in Karelia. On August 12, 1323, Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg, regulating their border for the first time.

The city’s downfall occurred partially as a result of its inability to feed its large population,[citation needed] making it dependent on the Vladimir-Suzdal region for grain. The main cities in the area, Moscow and Tver, used this dependence to gain control over Novgorod. Eventually Ivan III forcibly annexed the city to the Grand Duchy of Moscow in 1478. The Veche was dissolved and a significant part of Novgorod’s aristocracy, merchants and smaller landholding families was deported to central Russia. The Hanseatic League kontor was closed in 1494 and the goods stored there were seized by Muscovite forces.[30][31]

Tsardom of Russia[edit]

City plan of Novgorod in 1862

Kremlin square on postcard of the early XX century

At the time of annexation, Novgorod became the third largest city under Muscovy and then the Tsardom of Russia (with 5,300 homesteads and 25–30 thousand inhabitants in the 1550s[32]) and remained so until the famine of the 1560s and the Massacre of Novgorod in 1570. In the Massacre, Ivan the Terrible sacked the city, slaughtered thousands of its inhabitants, and deported the city’s merchant elite and nobility to Moscow, Yaroslavl and elsewhere. The last decade of the 16th century was a comparatively favourable period for the city as Boris Godunov restored trade privileges and raised the status of Novgorod bishop. The German trading post was reestablished in 1603.[33] Even after the incorporation into the Russian state Novgorod land retained its distinct identity and institutions, including the customs policy and administrative division. Certain elective offices were quickly restored after having been abolished by Ivan III.[34]

During the Time of Troubles, Novgorodians submitted to Swedish troops led by Jacob De la Gardie in the summer of 1611. The city was restituted to Muscovy six years later by the Treaty of Stolbovo. The conflict led to further depopulation: the number of homesteads in the city decreased from 1158 in 1607 to only 493 in 1617, with the Sofia side described as ‘deserted’.[35][36] Novgorod only regained a measure of its former prosperity towards the end of the century, when such ambitious buildings as the Cathedral of the Sign and the Vyazhischi Monastery were constructed. The most famous of Muscovite patriarchs, Nikon, was active in Novgorod between 1648 and 1652. The Novgorod Land became one of the Old Believers’ strongholds after the Schism.[33] The city remained an important trade centre even though it was now eclipsed by Archangelsk, Novgorodian merchants were trading in the Baltic cities and Stockholm while Swedish merchants came to Novgorod where they had their own trading post since 1627.[37] Novgorod continued to be a major centre of crafts which employed the majority of its population. There were more than 200 distinct professions in 16th century. Bells, cannons and other arms were produced in Novgorod; its silversmiths were famous for the skan’ technique used for religious items and jewellery. Novgorod chests were in widespread use all across Russia, including the Tsar’s household and the northern monasteries.[38]

Russian Empire[edit]

In 1727, Novgorod was made the administrative center of Novgorod Governorate of the Russian Empire, which was detached from Saint Petersburg Governorate (see Administrative divisions of Russia in 1727–1728). This administrative division existed until 1927. Between 1927 and 1944, the city was a part of Leningrad Oblast, and then became the administrative center of the newly formed Novgorod Oblast.

Modern era[edit]

On August 15, 1941, during World War II, the city was occupied by the German Army. Its historic monuments were systematically obliterated. The Red Army liberated the city on January 19, 1944. Out of 2,536 stone buildings, fewer than forty remained standing. After the war, thanks to plans laid down by Alexey Shchusev, the central part was gradually restored. In 1992, the chief monuments of the city and the surrounding area were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list as the Historic Monuments of Novgorod and Surroundings. In 1999, the city was officially renamed Veliky Novgorod (literally, Great Novgorod),[39] thus partly reverting to its medieval title «Lord Novgorod the Great». This reduced the temptation to confuse Veliky Novgorod with Nizhny Novgorod, a larger city the other side of Moscow which, between 1932 and 1990, had been renamed Gorky, in honour of Maxim Gorky.

Administrative and municipal status[edit]

Veliky Novgorod is the administrative center of the oblast and, within the framework of administrative divisions, it also serves as the administrative center of Novgorodsky District, even though it is not a part of it.[2] As an administrative division, it is incorporated separately as the city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod—an administrative unit with status equal to that of the districts.[2] As a municipal division, the city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod is incorporated as Veliky Novgorod Urban Okrug.[9]

Sights[edit]

The city is known for the variety and age of its medieval monuments. The foremost among these is the St. Sophia Cathedral, built between 1045 and 1050 under the patronage of Vladimir Yaroslavich, the son of Yaroslav the Wise; Vladimir and his mother, Anna Porphyrogenita, are buried in the cathedral.[40] It is one of the best preserved churches from the 11th century. It is also probably the oldest structure still in use in Russia and the first one to represent original features of Russian architecture (austere stone walls, five helmet-like domes). Its frescoes were painted in the 12th century originally on the orders of Bishop Nikita (died 1108) (the «porches» or side chapels were painted in 1144 under Archbishop Nifont) and renovated several times over the centuries, most recently in the nineteenth century.[41] The cathedral features famous bronze gates, which now hang in the west entrance, allegedly made in Magdeburg in 1156 (other sources see them originating from Płock in Poland) and reportedly snatched by Novgorodians from the Swedish town of Sigtuna in 1187. More recent scholarship has determined that the gates were most likely purchased in the mid-15th century, apparently at the behest of Archbishop Euthymius II (1429–1458), a lover of Western art and architectural styles.[42]

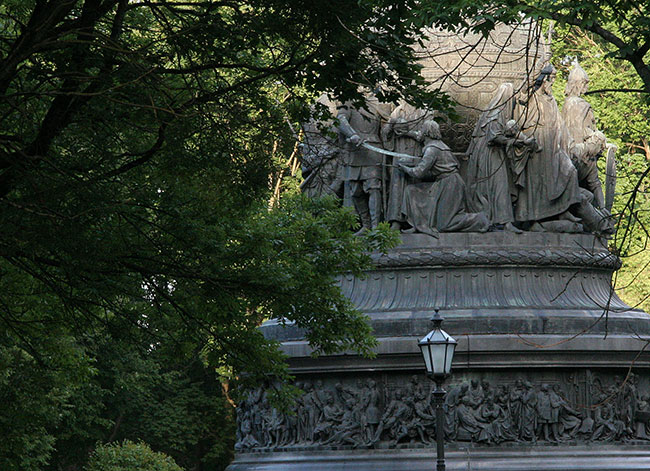

The Novgorod Kremlin, traditionally known as the Detinets, also contains the oldest palace in Russia (the so-called Chamber of the Facets, 1433), which served as the main meeting hall of the archbishops; the oldest Russian bell tower (mid-15th century), and the oldest Russian clock tower (1673). The Palace of Facets, the bell tower, and the clock tower were originally built on the orders of Archbishop Euphimius II, although the clock tower collapsed in the 17th century and had to be rebuilt and much of the palace of Euphimius II is no longer standing. Among later structures, the most remarkable are a royal palace (1771) and a bronze monument to the Millennium of Russia, representing the most important figures from the country’s history (unveiled in 1862).

Outside the Kremlin walls, there are three large churches constructed during the reign of Mstislav the Great. St. Nicholas Cathedral (1113–1123), containing frescoes of Mstislav’s family, graces Yaroslav’s Court (formerly the chief square of Novgorod). The Yuriev Monastery (one of the oldest in Russia, 1030) contains a tall, three-domed cathedral from 1119 (built by Mstislav’s son, Vsevolod, and Kyurik, the head of the monastery). A similar three-domed cathedral (1117), probably designed by the same masters, stands in the Antoniev Monastery, built on the orders of Antony, the founder of that monastery.

There are now some fifty medieval and early modern churches scattered throughout the city and its surrounding areas. [43] Some of them were blown up by the Nazis and subsequently restored. The most ancient pattern is represented by those dedicated to Saints Pyotr and Pavel (on the Swallow’s Hill, 1185–1192), to Annunciation (in Myachino, 1179), to Assumption (on Volotovo Field, 1180s) and to St. Paraskeva-Piatnitsa (at Yaroslav’s Court, 1207). The greatest masterpiece of early Novgorod architecture is the Savior church at Nereditsa (1198).

In the 13th century, tiny churches of the three-paddled design were in vogue. These are represented by a small chapel at the Peryn Monastery (1230s) and St. Nicholas’ on the Lipnya Islet (1292, also notable for its 14th-century frescoes). The next century saw the development of two original church designs, one of them culminating in St Theodor’s church (1360–1361, fine frescoes from 1380s), and another one leading to the Savior church on Ilyina street (1374, painted in 1378 by Feofan Grek). The Savior’ church in Kovalevo (1345) was originally frescoed by Serbian masters, but the church was destroyed during the war. While the church has since been rebuilt, the frescoes have not been restored.

During the last century of the republican government, some new churches were consecrated to Saints Peter and Paul (on Slavna, 1367; in Kozhevniki, 1406), to Christ’s Nativity (at the Cemetery, 1387), to St. John the Apostle’s (1384), to the Twelve Apostles (1455), to St Demetrius (1467), to St. Simeon (1462), and other saints. Generally, they are not thought[by whom?] to be as innovative as the churches from the previous period. Several shrines from the 12th century (i.e., in Opoki) were demolished brick by brick and then reconstructed exactly as they used to be, several of them in the mid-fifteenth century, again under Archbishop Yevfimy II (Euthymius II), perhaps one of the greatest patrons of architecture in medieval Novgorod.

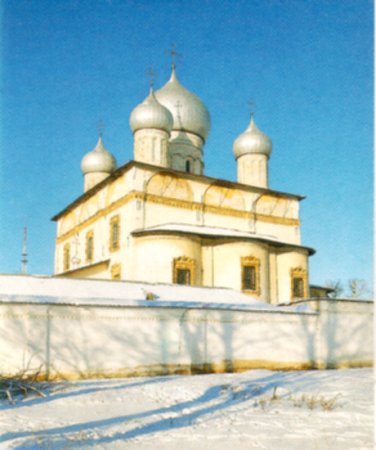

Novgorod’s conquest by Ivan III in 1478 decisively changed the character of local architecture. Large commissions were thenceforth executed by Muscovite masters and patterned after cathedrals of Moscow Kremlin: e.g., the Savior Cathedral of Khutyn Monastery (1515), the Cathedral of the Mother of God of the Sign (1688), the St. Nicholas Cathedral of Vyaschizhy Monastery (1685). Nevertheless, the styles of some parochial churches were still in keeping with local traditions: e.g., the churches of Myrrh-bearing Women (1510) and of Saints Boris and Gleb (1586).

In Vitoslavlitsy, along the Volkhov River and the Myachino Lake, close to the Yuriev Monastery, a museum of wooden architecture was established in 1964. Over twenty wooden buildings (churches, houses and mills) dating from the 14th to the 19th century were transported there from all around the Novgorod region.

11400 graves of the German 1st Luftwaffe Field Division are found at the war cemetery in Novgorod. Also 1900 soldiers of the Spanish Blue Division are buried there.[44]

-

Walls of the Novgorod Kremlin

-

War Memorial

-

-

Government Building

Transportation[edit]

Intercity transport[edit]

Novgorod main railway station, built in 1953

Novgorod has connections to Moscow (531 km) and St. Petersburg (189 km) by the federal highway M10. There are public buses to Saint Petersburg and other destinations.

The city has direct railway passenger connections with Moscow (Leningradsky Rail Terminal, by night trains), St. Petersburg (Moscow Rail Terminal and Vitebsk Rail Terminal, by suburban trains), Minsk (Belarus) (Minsk Passazhirsky railway station, by night trains) and Murmansk.

The city’s former commercial airport Yurievo was decommissioned in 2006, and the area has now been redeveloped into a residential neighbourhood. The still existing Krechevitsy Airport does not serve any regular flights since mid-1990s although there is a plan to turn Krechevitsy into a new operational airport by 2025.[45] The nearest international airport is St. Petersburg’s Pulkovo, some 180 kilometres (112 miles) north of the city.

Local transportation[edit]

Veliky Novgorod trolleybus map (2021)

Local transportation consists of a network of buses and trolleybuses. The trolleybus network, which currently consists of five routes, started operating in 1995 and is the first trolley system opened in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Honours[edit]

A minor planet, 3799 Novgorod, discovered by the Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1979, is named after the city.[46]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

|

|

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (March 2022) |

Veliky Novgorod is twinned with:[47][48]

Bielefeld, Germany

Kohtla-Järve, Estonia

Moss, Norway

Nanterre, France

Örebro, Sweden

Rochester, New York, USA

Uusikaupunki, Finland

Watford, UK

Zibo, China

See also[edit]

- Old Novgorod dialect

- Novgorod uprising of 1650

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Resolution #121

- ^ a b c d e f Law #559-OZ

- ^ According to Article 9 of the Charter of Veliky Novgorod, the symbols of Veliky Novgorod include a flag and a coat of arms but not an anthem.

- ^ a b Charter of Veliky Novgorod, Article 1

- ^ a b Charter of Veliky Novgorod, Article 6

- ^ Official website of Veliky Novgorod. Geographic Location (in Russian)

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ «26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года». Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Oblast Law #284-OZ

- ^ «Об исчислении времени». Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- ^ The Archaeology of Novgorod, by Valentin L. Yanin, in Ancient Cities, Special Issue, (Scientific American), pp. 120–127, c. 1994. Covers, History, Kremlin of Novgorod, Novgorod Museum of History, preservation dynamics of the soils, and the production of Birch bark documents.

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Всероссийская перепись населения 2020 года. Том 1 [2020 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1] (XLS) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ Crummey, R.O. (2014). The Formation of Muscovy 1300 — 1613. Taylor & Francis. p. 23. ISBN 9781317872009. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ Тихомиров, М.Н. (1956). Древнерусские города (in Russian). Государственное издательство Политической литературы. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Ketola, Kari; Vihavainen, Timo (2014). Changing Russia? : history, culture and business (1. ed.). Helsinki: Finemor. p. 1. ISBN 9527124018.

- ^ Valentin Lavrentyevich Ianin and Mark Khaimovich Aleshkovsky. «Proskhozhdeniye Novgoroda: (k postanovke problemy),» Istoriya SSSR 2 (1971): 32-61.

- ^ The name Holmgard is a Norse toponym meaning Islet town or Islet grad, and there are various explanations for why they gave this name. According to Rydzevskaya, the Norse name is derived from the Slavic Holmgrad which means «town on a hill» and may allude to the «old town» preceding the «new town», or Novgorod.

- ^ «Vnovgorod.info» Городище (in Russian). Великий Новгород. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ Mägi, Marika (2018). In Austrvegr: The Role of the Eastern Baltic in Viking Age Communication across the Baltic Sea. Brill. pp. 160–161. ISBN 9789004363816.

- ^ Franklin, Simon; Shepard, Jonathan (2014). The Emergence of Russia 750-1200. Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 9781317872245.

- ^ «The Cronicle of the Hanseatic League». european-heritage.org. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ Justyna Wubs-Mrozewicz, Traders, ties and tensions: the interactions of Lübeckers, Overijsslers and Hollanders in Late Medieval Bergen, Uitgeverij Verloren, 2008 p. 111

- ^ Translation of the grant of privileges to merchants in 1229: «Medieval Sourcebook: Privileges Granted to German Merchants at Novgorod, 1229». Fordham.edu. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ Michael C. Paul, «The Iaroslavichi and the Novgorodian Veche 1230–1270: A Case Study on Princely Relations with the Veche», Russian History/ Histoire Russe 31, No. 1-2 (Spring-Summer 2004): 39-59.

- ^ Michael C. Paul, «Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest». Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 8, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 231-270.

- ^ Michael C. Paul, «Episcopal Election in Novgorod, Russia 1156–1478». Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 72, No. 2 (June 2003): 251-275.

- ^ Janet Martin, Treasure of the Land of Darkness: the Fur Trade and its Significance for Medieval Russia. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

- ^ Janet Martin, “Les Uškujniki de Novgorod: Marchands ou Pirates.” Cahiers du Monde Russe et Sovietique 16 (1975): 5-18.

- ^ Kollmann, Nancy Shields (2017). The Russian Empire 1450-1801. Oxford University Press. p. 50.

- ^ Kazakova, N. A. (1984). «Еще раз о закрытии Ганзейского двора в Новгороде в 1494 г.». Новгородский исторический сборник. 2 (12): 177.

- ^ Boris Zemtsov, Откуда есть пошла… российская цивилизация, Общественные науки и современность. 1994. № 4. С. 51-62. p. 9 (in Russian)

- ^ a b Kovalenko, Guennadi (2010). Великий Новгород. Взгляд из Европы XV-XIX centuries (in Russian). Европейский Дом. pp. 48, 72, 73. ISBN 9785801502373.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in Russian). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ J.T., Russia’s Foreign Trade and Economic Expansion in the Seventeenth Century: Windows on the World (2005). Kotilaine. Brill. p. 30. ISBN 9789004138964.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in Russian). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. pp. 44, 45. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in Russian). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. p. 71. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in Russian). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. pp. 52–60. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ «Федеральный закон от 11.06.1999 г. № 111-ФЗ». kremlin.ru.

- ^ Tatiana Tsarevskaia, St. Sophia’s Cathedral in Novgorod (Moscow: Severnyi Palomnik, 2005), 3.

- ^ Tsarevskaia, 14, 19-22, 24, 29, 35.

- ^ Jadwiga Irena Daniec, The Message of Faith and Symbol in European Medieval Bronze Church Doors (Danbury, CT: Rutledge Books, 1999), Chapter III «An Enigma: The Medieval Bronze Church Door of Płock in the Cathedral of Novgorod,» 67-97; Mikhail Tsapenko, ed., Early Russian Architecture (Moscow: Progress Publisher, 1969), 34-38

- ^ Vdovichenko, Marina (2020). «Medieval Churches in Novgorod: Aspects of archaeological investigations and museum presentation». Internet Archaeology (54). doi:10.11141/ia.54.10.

- ^ de:Kriegsgräberstätte Nowgorod

- ^ «Аэропорт Кречевицы начнёт работать в 2025 году». September 4, 2019.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 321. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- ^ «Международные культурные связи». adm.nov.ru (in Russian). Veliky Novgorod. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ «Ystävyyskaupungit». seinajoki.fi (in Finnish). Seinäjoki. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

Sources[edit]

- Дума Великого Новгорода. Решение №116 от 28 апреля 2005 г. «Устав муниципального образования – городского округа Великий Новгород», в ред. Решения №515 от 11 июня 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в Устав муниципального образования – городского округа Великий Новгород». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования, но не ранее 1 января 2006 года, за исключением статей, для которых подпунктом 5.1 установлены иные сроки вступления в силу. (Duma of Veliky Novgorod. Decision #116 of April 28, 2005 Charter of the Municipal Formation–Veliky Novgorod Urban Okrug, as amended by the Decision #515 of June 11, 2015 On Amending the Charter of the Municipal Formation–Veliky Novgorod Urban Okrug. Effective as of the day of official publication but not earlier than January 1, 2006, with the exception of the clauses for which subitem 5.1 establishes other dates of taking effect.).

- Администрация Новгородской области. Постановление №121 от 8 апреля 2008 г. «Об реестре административно-территориального устройства области», в ред. Постановления №408 от 4 августа 2014 г. «О внесении изменений в реестр административно-территориального устройства области». Опубликован: «Новгородские ведомости», №49–50, 16 апреля 2008 г. (Administration of Novgorod Oblast. Resolution #121 of April 8, 2008 On the Registry of the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Novgorod Oblast, as amended by the Resolution #408 of August 4, 2014 On Amending the Registry of the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Novgorod Oblast. ).

- Новгородская областная Дума. Областной закон №284-ОЗ от 7 июня 2004 г. «О наделении сельских районов и города Великий Новгород статусом муниципальных районов и городского округа Новгородской области и утверждении границ их территорий», в ред. Областного закона №802-ОЗ от 31 августа 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в некоторые областные Законы, устанавливающие границы муниципальных образований». Вступил в силу со дня, следующего за днём официального опубликования. Опубликован: «Новгородские ведомости», №86, 22 июня 2004 г. (Novgorod Oblast Duma. Oblast Law #284-OZ of June 7, 2004 On Granting the Status of Municipal Districts and Urban Okrug of Novgorod Oblast to the Rural Districts and the City of Veliky Novgorod and on Establishing the Borders of Their Territories, as amended by the Oblast Law #802-OZ of August 31, 2015 On Amending Various Oblast Laws Establishing the Borders of the Municipal Formations. Effective as of the day following the day of the official publication.).

- Государственная Дума Российской Федерации. Федеральный закон №111-ФЗ от 11 июня 1999 г. «О переименовании города Новгорода — административного центра Новгородской области в город Великий Новгород». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: «Собрание законодательства РФ», №24, ст. 2892, 14 июня 1999 г. (State Duma of the Russian Federation. Federal Law #111-FZ of June 11, 1999 On Renaming the City of Novgorod—the Administrative Center of Novgorod Oblast—the City of Veliky Novgorod. Effective as of the day of official publication.).

- William Craft Brumfield. A History of Russian Architecture (Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 2004) ISBN 978-0-295-98394-3

- Peter Bogucki. Novgorod (in Lost Cities; 50 Discoveries in World Archaeology, edited by Paul G. Bahn: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1997) ISBN 0-7607-0756-1

External links[edit]

Media related to Velikiy Novgorod at Wikimedia Commons

Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Novgorod.

- Official website of Veliky Novgorod (in Russian)

- Veliky Novgorod City Portal

- Veliky Novgorod for tourists

- The Faceted Palace of the Kremlin in Novgorod the Great site

- Veliky Novgorod’s architecture and buildings history

- William Coxe (1784), «Novogorod», Travels into Poland, Russia, Sweden and Denmark, London: Printed by J. Nichols, for T. Cadell, OCLC 654136, OL 23349695M

- Annette M. B. Meakin (1906). «Novgorod the Great». Russia, Travels and Studies. London: Hurst and Blackett. OCLC 3664651. OL 24181315M.

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). «Novgorod (government)» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). p. 839.

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). «Novgorod (town)» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). pp. 839–840.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Перевод «великий новгород» на английский

С 1998 года официальное название города — Великий Новгород.

Since 1998, the official name of the city is Veliky Novgorod.

В итоге было решено транспортировать корпус реактора через Великий Новгород.

As a result, it was decided to transport the reactor vessel through Veliky Novgorod.

Школьники с большим удовольствием осматривают Великий Новгород.

Students with great pleasure visiting Novgorod.

По преданию, этот чудотворный образ в 1170 году. спас Великий Новгород от врагов.

In 1170 this miraculous icon saved Novgorod from the invasion of enemies.

Вода затопила дороги, мосты и даже частично город Великий Новгород.

Water flooded roads, bridges and even the city of Veliky Novgorod in part.

После экскурсии переезд в Великий Новгород.

Великий Новгород тоже богат выдающимися средневековыми достопримечательностями.

Великий Новгород отметил свои 1158 лет.

Veliky Novgorod celebrated its existence of 1155 years in 2014.

Начиная с XI века Великий Новгород был центром культуры и образования.

Since the XI century, Veliky Novgorod was the center of culture and education.

Наиболее известным является блюдо Судак «Великий новгород«.

Великий Новгород — город очень значимый для истории российской государственности.

Veliky Novgorod is a city of great importance to the history of Russia.

Великий Новгород — его по праву считают отцом российских городов.

Veliky Novgorod — he is rightly considered the father of Russian cities.

Недавно я посетил древний русский город Великий Новгород.

Великий Новгород — это шанс узнать достоверную историю Руси.

Veliky Novgorod is a chance to learn the authentic history of Russia.

Экскурсионные туры в Великий Новгород превращаются в увлекательное путешествие по богатейшей сокровищнице Древней Руси.

Sightseeing tours in Veliky Novgorod turn into a fascinating journey through the rich treasury of ancient Russia.

Однажды я уже туда собирался, но тогда не оказалось билетов и я уехал в Великий Новгород.

Once I was going there, but then there were no tickets and I went to Veliky Novgorod.

Помимо внушительного разнообразия церквей и храмов (на самом деле Великий Новгород может похвастаться около 60 действующими и закрытыми религиозными зданиями).

Apart from an impressive variety of churches and temples (in fact, Veliky Novgorod boasts around 60 functioning and closed religious edifices).

Как одеться если вы едете в Великий Новгород

Ежегодная поездка 2016 в Великий Новгород: возвращение древней традиции

Annual trip 2016 to Veliky Novgorod: the return of an ancient tradition

Подлодка Великий Новгород прошла все государственные испытания и подтвердила все боевые характеристики.

The submarine Veliky Novgorod passed all state trials and confirmed all its combat capabilities.

Результатов: 348. Точных совпадений: 348. Затраченное время: 60 мс

Welcome to Velikiy Novgorod

General information

Velikiy Novgorod — one of the most ancient cities of Russia located in its North-West, near the site where the Volkhov river takes its waters from Lake Ilmen, emerged as a political center of Slavic and Fino-Ugric tribes in the mid-9th century, while as a town it was formed in the middle of the 10th century.

Alexander Nevsky Embankment

The history of Novgorod is closely linked with all major stages in the life of the Russian state. In those times, when the statehood of Rus was just in the making, the Novgorodians invited Scandinavian prince Rurik to keep law and order, thus giving birth to the prince Rurik dynasty that ruled over all Russian lands throughout more than 750 years.

St. Sophia Cathedral 1045 — 1050

In the early 10th century, war campaigns of the Novgorodians against Constantinople to secure equal trade with Bizantine resulted in the integration of East Slavic tribes into the ancient Kievan Russian state.

Fresco «Apostle Peter»

The adoption of Christianity at the close of the tenth century turned Novgorod into a powerful ecclesiastical center. The efforts of Novgorod Bishops in spreading and promoting the Orthodoxy were given high credit in the mid-12th century when they were elevated to the ranks of Archbishops which made the Bishops Chair of Novgorod the most powerful in the Russian Orthodoxy.

Monument to the Millenium of Russia

The right of Novgorod to select its own princes, that was granted in the middle of the twelfth century, attracted princes to the Novgorod throne. This provided favorable conditions to maintain the unity of Russian lands tending to be feudally divided, while the annexation of the Novgorod republic to the Moscow Principality at the end of the 15th century resulted in the united Russian State with Moscow as the capital.

Throughout many centuries, Novgorod was a political center of vast territories stretching up from the Baltic lands and Finland in the West to the northern Urals in the East. It was also one of the greatest international trade centers on the Baltic-Volga commercial route that tied northern Europe with Asia as early as the mid — 8th century.

Kremlin Intercession Tower. 16th 17th cc.

Novgorod is the cradle of Russian republican and democratic traditions. In the course of over 600 years, up till 1478, all vital decisions on its life and foreign policy were taken by the «veche» — an ancient parliament comprising the representatives of the town aristocracy families. At crucial times of Novgorod’s history, every citizen took part in the veche.

The republic’s special political structure, spiritual freedom and territorial independence were highly favorable to the evolution of culture and art.

Novgorod was one of Russia’s major centers of literacy and book production. As far back as in the 30-s of the 11th century, by the will of the great Prince Yaroslav The Wise, Novgorod saw the first school to train three hundred children at a time.

Medieval Novgorod was one of the greatest art centers of Europe. Its architectural traditions, school of icon-painting, jeweler’s and decorative applied art became famous all over the world.

Church of Our Saviour on Nereditsa

The town’s military power, its remoteness from dangerous southern borders, successful campaigns against clergical reforms and heresies enabled the city to preserve a unique complex of architectural monuments with frescoes of the 11th — 17th centuries, the oldest Russian manuscripts, chronicles, acts, icons. The only time in its history when Novgorod suffered military damages was in the course of World War II: for over two years the city, being at the front line, was bombed and shelled by both combating armies. Turned into ruins, this city on the Volkhov River was brought to life again by the restorers who managed to revive the old architecture. Welcome to Novgorod! You will be able to visit a unique complex of ancient Russian architectural monuments of the 11th — 17th centuries.

Fresco «St. Ustinia» (church of Our Saviour on Nereditsa)

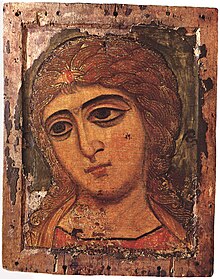

First of all you will be fascinated by the cathedral of St. Sophia, the Holy Wisdom of God — the oldest surviving Russian stone monument. It was built in 1045. The powerful monolithic massive structure of the monument still dominates not only the Kremlin, but the whole historic downtown of Novgorod. In the interior of this palladion your attention will be drawn by the unique historically formed iconostases, ancient mural paintings, icons — national relics of Russia (including the famous icon of the 12th century — Virgin of the Sign, that was returned back to the cathedral in 1991, when divine services were resumed here), and other relics of Byzantine, Western Europe and Russian art. In the course of hundreds of years the Cathedral of St. Sophia was a center of the clergical, political and cultural life of ancient Novgorod.

You are welcome to admire the monuments of twelfth century Novgorod architecture — the Cathedral of St. Nicholas in Yaroslav’s Court and the Church of the Nativity of Our Lady in St. Anthony’s Monastery, that have brought to us old fresco painting, carved iconostases, and the necropolis of the 17th — 18th centuries. In the old cloister — the St. George (Yuriev) Monastery, that was founded as early as in the 12th century by Prince Yaroslav the Wise, as a legend reads, one cannot help being amazed by the striking beauty of another masterpiece of ancient Russian architecture — the Cathedral of St. George, built by a certain master mason Peter in 1119.

Archaeological finds from the Museum

Many experts of Russian art justly believe Novgorod to be a Russian Florence; no other old Russian cities have managed to preserve so many ancient architectural monuments adorned with wall murals. You will see that with your own eyes visiting the churches of Our Saviour on Nereditsa Hill and Annunciation of Our Lady on Miachino Lake (12th century): appreciating at its true worth the 14th century frescoes of world-famous Theophanes the Greek in the church of the Transfiguration of Our Saviour on Iliah Street; singularly graceful murals in the churches of the Nativity of Our Lady on Krasnoye Field, St. Theodore Stratilates on the Brook, admiring the beautiful clergical wall calendar of the 15th — 17th centuries in the Church of St. Simeon The Godreceiver: and studying wonderful mural compositions of the late 17th — early 18th centuries in The Virgin of The Sign Cathedral.

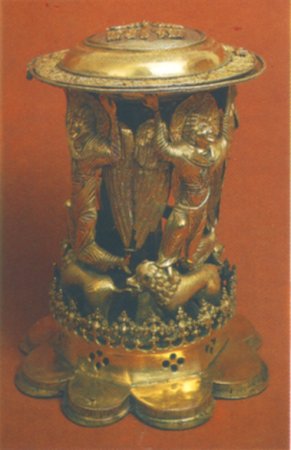

Great St. Sophia Zion.

You will, no doubt, be happy with a visit of the Kremlin of Novgorod — the oldest in Russia. This fortress was mentioned in chronicles as early as 1044. The present walls and towers were constructed at the close of the 15th century. The Detinets (that was the original name of the citadel ) was closely related to all the most important events in the life of ancient Novgorod: hosting foreign embassies, seeing-off warriors to fight the enemy, convening veche meetings. In addition to the above-mentioned St. Sophia’s Cathedral, the Kremlin also features such other striking monuments as the Faceted (Archbishop’s) Palace — a rare specimen of Gothic architecture, built in 1433 jointly with German masters, as well as the impressive and beautiful St. Sophia’s Bellfry of 1439 with a set of bells dating back to the 16th — 18th cc.

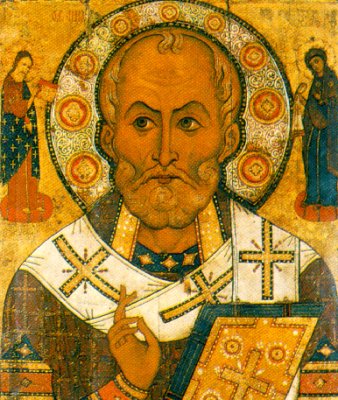

Icon «St. Nicolas»

In the central square of the Kremlin stands the monument «The Millenium of Russia», designed by Mikhail Mikeshin and erected in 1862. This unique document in bronze immortalizes all those who greatly contributed (in addition to the outstanding Russian politicians) to the development of the country: its culture, science, art, literacy, and literature. Leaving the Kremlin and St. Sophia Quarter of the city, you can get to the opposite bank of the Volkhov by a footbridge. Now we approach the territory of another architectural open-air museum: the Yaroslav’s Court and ancient Trade-yard, displaying many still-standing monuments of the 12th — 16th centuries: churches of St. John-The Baptist, Paraskeva-Pyatnitsa, Myrrh-Bearing Women and others — all reminiscent of the busy trade life of Novgorod in days goneby. Yaroslav Court, with its non-suviving wooden palace of Great Prince Yaroslav The Wise, was widely known since the middle of the 8th century as a site of the international Trade-yard, the oldest in northern Europe.

Wrap «Wirgin of the Sign with Selected Saints»

Shroud of Christ «Entombment». 15th c.

A visit to Novgorod usually leaves guests with unforgettable impressions of the inimitable and majestic Novgorod landscape. There are may enchanting sights on the boat tour of Lake Ilmen and the Volkhov river: Peryn — the site of the pre-Christian heathen temple; visiting Lipno island with one of the few preserved architectural specimens of the 13th century — the Church of St. Nicholas, decorated with frescoes of the same period.

Panagirion. 15th c. (Palace of Facets)

You are always welcome at the expositions and exhibitions of one of the most ancient and richest museums of Russia — Novgorod State United Museum, that offers visitors a unique collection of historic, cultural and art relics.

St. George Cathedral. 12th c. Yuriev Monastery

Of a special interest is the Museum’s archaeological collection, comprising all relics excavated from the soil of Novgorod in the archaeological research that has been carried out for more than 60 years. The archaeological finds include such world-famous items as a great number of birch-bark scrolls and lead seals dating back to the 12th — 15th centuries. These are indicative of a unique and striking (for medieval times) level of literacy among ancient Russians and also of a highly organized system of state control. The unprecedented rich collection of archaeological relics provides a basis for one of the best Russian historic expositions — the one called «Great Novgorod. Policy. Economy. Culture. 10th — 15th centuries «. It is displayed in the Kremlin’s former

Yuriev Monastery

world-famous Novgorod Museum collection of Novgorod school of icon painting covering the 12th — 15th centuries. This can only be thoroughly studied in Novgorod. Not even Moscow or St. Petersburg has this quality of subject matter. A suite of rooms on the second floor of the museum contains the artworks that can be studied.

Virgin of Sign Cathedral. Late 17th c.

It is also only in Novgorod that visitors can admire a unique collection of facial and ornamental embroidery of the 16th — 17th centuries. Exhibited in the Kremlin’s St. Ioann building, it features such wonderful works of ancient Russian embroideries as maniples of St. Varlaam of Khutyn (12th c.), shroud, commissioned by Dmitry Shemyaka (15th c.), omophorion of Nicon (17th c.), etc.

Of no less interest is the exhibition of ancient jewelry and decorative-applied art of the 10th to early 20th centuries, which is on display in the main hall of the Faceted (Archbishop’s) Palace of the Kremlin. Many of them are indeed unique: Zions from St. Sophia vestry (12th century), Craters of the 12th century, cloisonne enamels (10th — 12th centuries), panagiarion from the vestry of St. Sophia Cathedral (15th century), panagia of Archbishop Pimen (16th century).

Yaroslav’s Court and Ancient Torg

The open-air architectural-ethnographic museum «Vitoslavlitsy» provides a whole complex of genuine folk wooden architecture, including ancient churches of the 16th — 18th centuries and peasant houses of the 19th — early 20th centuries, exhibitions of folk art and everyday life items of Novgorod peasants of the same period.

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Week In Review

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history. - Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Britannica Beyond

We’ve created a new place where questions are at the center of learning. Go ahead. Ask. We won’t mind. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

|

Veliky Novgorod Великий Новгород |

|

|---|---|

|

City[1] |

|

Counter-clockwise from top right: the Millennium of Russia, cathedral of St. Sophia, the fine arts museum, St. George’s Monastery, the Kremlin, Yaroslav’s Court |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: none[3] | |

|

Location of Veliky Novgorod |

|

|

Veliky Novgorod Location of Veliky Novgorod Veliky Novgorod Veliky Novgorod (European Russia) Veliky Novgorod Veliky Novgorod (Europe) |

|

| Coordinates: 58°33′N 31°16′E / 58.550°N 31.267°ECoordinates: 58°33′N 31°16′E / 58.550°N 31.267°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Novgorod Oblast[2] |

| First mentioned | 859[4] |

| Government | |

| • Body | Duma[5] |

| • Mayor (Head)[5] | Aleksandr Rozbaum |

| Area

[6] |

|

| • Total | 90 km2 (30 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 25 m (82 ft) |

| Population

(2010 Census)[7] |

|

| • Total | 218,717 |

| • Estimate

(2018)[8] |

222,868 (+1.9%) |

| • Rank | 85th in 2010 |

| • Density | 2,400/km2 (6,300/sq mi) |

|

Administrative status |

|

| • Subordinated to | city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod[2] |

| • Capital of | Novgorod Oblast[2], city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod[2] |

|

Municipal status |

|

| • Urban okrug | Veliky Novgorod Urban Okrug[9] |

| • Capital of | Veliky Novgorod Urban Okrug[9], Novgorodsky Municipal District[9] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| Postal code(s)[11] |

173000–173005, 173007–173009, 173011–173016, 173018, 173020–173025, 173700, 173899, 173920, 173955, 173990, 173999 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 8162 |

| OKTMO ID | 49701000001 |

| Website | www.adm.nov.ru |

Veliky Novgorod (Russian: Великий Новгород, IPA: [vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət], lit. ‘Great Newtown’), also known as just Novgorod (Новгород), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the oldest cities in Russia,[12] being first mentioned in the 9th century. The city lies along the Volkhov River just downstream from its outflow from Lake Ilmen and is situated on the M10 federal highway connecting Moscow and Saint Petersburg. UNESCO recognized Novgorod as a World Heritage Site in 1992. The city has a population of 224,286 (2021 Census).[13]

At its peak during the 14th century, the city was the capital of the Novgorod Republic and was one of Europe’s largest cities.[14] The «Veliky» («great») part was added to the city’s name in 1999.

History[edit]

Early developments[edit]

The Sofia First Chronicle makes initial mention of it in 859, while the Novgorod First Chronicle first mentions it in 862, when it was purportedly already a major Baltics-to-Byzantium station on the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks.[15] The Charter of Veliky Novgorod recognizes 859 as the year when the city was first mentioned.[4] Novgorod is traditionally considered to be a cradle of Russian statehood.[16]

The oldest archaeological excavations in the middle to late 20th century, however, have found cultural layers dating back to the late 10th century, the time of the Christianization of Rus’ and a century after it was allegedly founded.[17] Archaeological dating is fairly easy and accurate to within 15–25 years, as the streets were paved with wood, and most of the houses made of wood, allowing tree ring dating.

The Varangian name of the city Holmgård or Holmgard (Holmgarðr or Holmgarðir) is mentioned in Norse Sagas as existing at a yet earlier stage, but the correlation of this reference with the actual city is uncertain.[18] Originally, Holmgård referred to the stronghold, now only 2 km (1.2 miles) to the south of the center of the present-day city, Rurikovo Gorodische (named in comparatively modern times after the Varangian chieftain Rurik, who supposedly made it his «capital» around 860). Archaeological data suggests that the Gorodishche, the residence of the Knyaz (prince), dates from the mid-9th century,[19] whereas the town itself dates only from the end of the 10th century; hence the name Novgorod, «new city», from Old East Slavic Новъ and Городъ (Nov and Gorod); the Old Norse term Nýgarðr is a calque of an Old Russian word. First mention of this Norse etymology to the name of the city of Novgorod (and that of other cities within the territory of the then Kievan Rus’) occurs in the 10th-century policy manual De Administrando Imperio by Byzantine emperor Constantine VII.

Princely state within Kievan Rus’[edit]

In 882, Rurik’s successor, Oleg of Novgorod, conquered Kiev and founded the state of Kievan Rus’. Novgorod’s size as well as its political, economic, and cultural influence made it the second most important city in Kievan Rus’. According to a custom, the elder son and heir of the ruling Kievan monarch was sent to rule Novgorod even as a minor. When the ruling monarch had no such son, Novgorod was governed by posadniks, such as the legendary Gostomysl, Dobrynya, Konstantin, and Ostromir.

Of all their princes, Novgorodians most cherished the memory of Yaroslav the Wise, who sat as Prince of Novgorod from 1010 to 1019, while his father, Vladimir the Great, was a prince in Kiev. Yaroslav promulgated the first written code of laws (later incorporated into Russkaya Pravda) among the Eastern Slavs and is said to have granted the city a number of freedoms or privileges, which they often referred to in later centuries as precedents in their relations with other princes. His son, Vladimir, sponsored construction of the great St. Sophia Cathedral, more accurately translated as the Cathedral of Holy Wisdom, which stands to this day.

Early foreign ties[edit]

In Norse sagas the city is mentioned as the capital of Gardariki.[20] Many Viking kings and yarls came to Novgorod seeking refuge or employment, including Olaf I of Norway, Olaf II of Norway, Magnus I of Norway, and Harald Hardrada.[21] No more than a few decades after the 1030 death and subsequent canonization of Olaf II of Norway, the city’s community had erected in his memory Saint Olaf’s Church in Novgorod.

The Gotland town of Visby functioned as the leading trading center in the Baltic before the Hansa League. At Novgorod in 1080, Visby merchants established a trading post which they named Gutagard (also known as Gotenhof).[22] Later, in the first half of the 13th century, merchants from northern Germany also established their own trading station in Novgorod, known as Peterhof.[23] At about the same time, in 1229, German merchants at Novgorod were granted certain privileges, which made their position more secure.[24]

Novgorod Republic[edit]

In 1136, the Novgorodians dismissed their prince Vsevolod Mstislavich. The year is seen as the traditional beginning of the Novgorod Republic. The city was able to invite and dismiss a number of princes over the next two centuries, but the princely office was never abolished and powerful princes, such as Alexander Nevsky, could assert their will in the city regardless of what Novgorodians said.[25] The city state controlled most of Europe’s northeast, from lands east of today’s Estonia to the Ural Mountains, making it one of the largest states in medieval Europe, although much of the territory north and east of Lakes Ladoga and Onega was sparsely populated and never organized politically.

One of the most important local figures in Novgorod was the posadnik, or mayor, an official elected by the public assembly (called the Veche) from among the city’s boyars, or aristocracy. The tysyatsky, or «thousandman», originally the head of the town militia but later a commercial and judicial official, was also elected by the Veche. Another important local official was the Archbishop of Novgorod who shared power with the boyars.[26] Archbishops were elected by the Veche or by the drawing of lots, and after their election, were sent to the metropolitan for consecration.[27]

While a basic outline of the various officials and the Veche can be drawn up, the city-state’s exact political constitution remains unknown. The boyars and the archbishop ruled the city together, although where one official’s power ended and another’s began is uncertain. The prince, although his power was reduced from around the middle of the 12th century, was represented by his namestnik, or lieutenant, and still played important roles as a military commander, legislator and jurist. The exact composition of the Veche, too, is uncertain, with some historians, such as Vasily Klyuchevsky, claiming it was democratic in nature, while later scholars, such as Marxists Valentin Ianin and Aleksandr Khoroshev, see it as a «sham democracy» controlled by the ruling elite.

In the 13th century, Novgorod, while not a member of the Hanseatic League, was the easternmost kontor, or entrepôt, of the league, being the source of enormous quantities of luxury (sable, ermine, fox, marmot) and non-luxury furs (squirrel pelts).[28]

Throughout the Middle Ages, the city thrived culturally. A large number of birch bark letters have been unearthed in excavations, perhaps suggesting widespread literacy. It was in Novgorod that the Novgorod Codex, the oldest Slavic book written north of Bulgaria, and the oldest inscription in a Finnic language (Birch bark letter no. 292) were unearthed. Some of the most ancient Russian chronicles (Novgorod First Chronicle) were written in the scriptorium of the archbishops who also promoted iconography and patronized church construction. The Novgorod merchant Sadko became a popular hero of Russian folklore.

Novgorod was never conquered by the Mongols during the Mongol invasion of Rus. The Mongol army turned back about 200 kilometers (120 mi) from the city, not because of the city’s strength, but probably because the Mongol commanders did not want to get bogged down in the marshlands surrounding the city. However, the grand princes of Moscow, who acted as tax collectors for the khans of the Golden Horde, did collect tribute in Novgorod, most notably Yury Danilovich and his brother, Ivan Kalita.

The 16th century Vision of Tarasius icon depicts Novgorod with the Sofia side to the left and the Commercial side to the right. The inhabitants of the city are shown doing their day-to-day work while being guarded by the angels

In 1259, Mongol tax-collectors and census-takers arrived in the city, leading to political disturbances and forcing Alexander Nevsky to punish a number of town officials (he cut off their noses) for defying him as Grand Prince of Vladimir (soon to be the khan’s tax-collector in Russia) and his Mongol overlords. In the 14th century, raids by Novgorod pirates, or ushkuiniki,[29] sowed fear as far as Kazan and Astrakhan, assisting Novgorod in wars with the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

During the era of Old Rus’ State, Novgorod was a trade hub at the northern end of both the Volga trade route and the «route from the Varangians to the Greeks» along the Dnieper river system. A vast array of goods were transported along these routes and exchanged with local Novgorod merchants and other traders. The farmers of Gotland retained the Saint Olof trading house well into the 12th century. Later German merchantmen also established tradinghouses in Novgorod. Scandinavian royalty would intermarry with Russian princes and princesses.

After the great schism, Novgorod struggled from the beginning of the 13th century against Swedish, Danish, and German crusaders. During the Swedish-Novgorodian Wars, the Swedes invaded lands where some of the population had earlier paid tribute to Novgorod. The Germans had been trying to conquer the Baltic region since the late 12th century. Novgorod went to war 26 times with Sweden and 11 times with the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. The German knights, along with Danish and Swedish feudal lords, launched a series of uncoordinated attacks in 1240–1242. Novgorodian sources mention that a Swedish army was defeated in the Battle of the Neva in 1240. The Baltic German campaigns ended in failure after the Battle on the Ice in 1242. After the foundation of the castle of Viborg in 1293 the Swedes gained a foothold in Karelia. On August 12, 1323, Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg, regulating their border for the first time.

The city’s downfall occurred partially as a result of its inability to feed its large population,[citation needed] making it dependent on the Vladimir-Suzdal region for grain. The main cities in the area, Moscow and Tver, used this dependence to gain control over Novgorod. Eventually Ivan III forcibly annexed the city to the Grand Duchy of Moscow in 1478. The Veche was dissolved and a significant part of Novgorod’s aristocracy, merchants and smaller landholding families was deported to central Russia. The Hanseatic League kontor was closed in 1494 and the goods stored there were seized by Muscovite forces.[30][31]

Tsardom of Russia[edit]

City plan of Novgorod in 1862

Kremlin square on postcard of the early XX century

At the time of annexation, Novgorod became the third largest city under Muscovy and then the Tsardom of Russia (with 5,300 homesteads and 25–30 thousand inhabitants in the 1550s[32]) and remained so until the famine of the 1560s and the Massacre of Novgorod in 1570. In the Massacre, Ivan the Terrible sacked the city, slaughtered thousands of its inhabitants, and deported the city’s merchant elite and nobility to Moscow, Yaroslavl and elsewhere. The last decade of the 16th century was a comparatively favourable period for the city as Boris Godunov restored trade privileges and raised the status of Novgorod bishop. The German trading post was reestablished in 1603.[33] Even after the incorporation into the Russian state Novgorod land retained its distinct identity and institutions, including the customs policy and administrative division. Certain elective offices were quickly restored after having been abolished by Ivan III.[34]

During the Time of Troubles, Novgorodians submitted to Swedish troops led by Jacob De la Gardie in the summer of 1611. The city was restituted to Muscovy six years later by the Treaty of Stolbovo. The conflict led to further depopulation: the number of homesteads in the city decreased from 1158 in 1607 to only 493 in 1617, with the Sofia side described as ‘deserted’.[35][36] Novgorod only regained a measure of its former prosperity towards the end of the century, when such ambitious buildings as the Cathedral of the Sign and the Vyazhischi Monastery were constructed. The most famous of Muscovite patriarchs, Nikon, was active in Novgorod between 1648 and 1652. The Novgorod Land became one of the Old Believers’ strongholds after the Schism.[33] The city remained an important trade centre even though it was now eclipsed by Archangelsk, Novgorodian merchants were trading in the Baltic cities and Stockholm while Swedish merchants came to Novgorod where they had their own trading post since 1627.[37] Novgorod continued to be a major centre of crafts which employed the majority of its population. There were more than 200 distinct professions in 16th century. Bells, cannons and other arms were produced in Novgorod; its silversmiths were famous for the skan’ technique used for religious items and jewellery. Novgorod chests were in widespread use all across Russia, including the Tsar’s household and the northern monasteries.[38]

Russian Empire[edit]

In 1727, Novgorod was made the administrative center of Novgorod Governorate of the Russian Empire, which was detached from Saint Petersburg Governorate (see Administrative divisions of Russia in 1727–1728). This administrative division existed until 1927. Between 1927 and 1944, the city was a part of Leningrad Oblast, and then became the administrative center of the newly formed Novgorod Oblast.

Modern era[edit]

On August 15, 1941, during World War II, the city was occupied by the German Army. Its historic monuments were systematically obliterated. The Red Army liberated the city on January 19, 1944. Out of 2,536 stone buildings, fewer than forty remained standing. After the war, thanks to plans laid down by Alexey Shchusev, the central part was gradually restored. In 1992, the chief monuments of the city and the surrounding area were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list as the Historic Monuments of Novgorod and Surroundings. In 1999, the city was officially renamed Veliky Novgorod (literally, Great Novgorod),[39] thus partly reverting to its medieval title «Lord Novgorod the Great». This reduced the temptation to confuse Veliky Novgorod with Nizhny Novgorod, a larger city the other side of Moscow which, between 1932 and 1990, had been renamed Gorky, in honour of Maxim Gorky.

Administrative and municipal status[edit]

Veliky Novgorod is the administrative center of the oblast and, within the framework of administrative divisions, it also serves as the administrative center of Novgorodsky District, even though it is not a part of it.[2] As an administrative division, it is incorporated separately as the city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod—an administrative unit with status equal to that of the districts.[2] As a municipal division, the city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod is incorporated as Veliky Novgorod Urban Okrug.[9]

Sights[edit]

The city is known for the variety and age of its medieval monuments. The foremost among these is the St. Sophia Cathedral, built between 1045 and 1050 under the patronage of Vladimir Yaroslavich, the son of Yaroslav the Wise; Vladimir and his mother, Anna Porphyrogenita, are buried in the cathedral.[40] It is one of the best preserved churches from the 11th century. It is also probably the oldest structure still in use in Russia and the first one to represent original features of Russian architecture (austere stone walls, five helmet-like domes). Its frescoes were painted in the 12th century originally on the orders of Bishop Nikita (died 1108) (the «porches» or side chapels were painted in 1144 under Archbishop Nifont) and renovated several times over the centuries, most recently in the nineteenth century.[41] The cathedral features famous bronze gates, which now hang in the west entrance, allegedly made in Magdeburg in 1156 (other sources see them originating from Płock in Poland) and reportedly snatched by Novgorodians from the Swedish town of Sigtuna in 1187. More recent scholarship has determined that the gates were most likely purchased in the mid-15th century, apparently at the behest of Archbishop Euthymius II (1429–1458), a lover of Western art and architectural styles.[42]

The Novgorod Kremlin, traditionally known as the Detinets, also contains the oldest palace in Russia (the so-called Chamber of the Facets, 1433), which served as the main meeting hall of the archbishops; the oldest Russian bell tower (mid-15th century), and the oldest Russian clock tower (1673). The Palace of Facets, the bell tower, and the clock tower were originally built on the orders of Archbishop Euphimius II, although the clock tower collapsed in the 17th century and had to be rebuilt and much of the palace of Euphimius II is no longer standing. Among later structures, the most remarkable are a royal palace (1771) and a bronze monument to the Millennium of Russia, representing the most important figures from the country’s history (unveiled in 1862).

Outside the Kremlin walls, there are three large churches constructed during the reign of Mstislav the Great. St. Nicholas Cathedral (1113–1123), containing frescoes of Mstislav’s family, graces Yaroslav’s Court (formerly the chief square of Novgorod). The Yuriev Monastery (one of the oldest in Russia, 1030) contains a tall, three-domed cathedral from 1119 (built by Mstislav’s son, Vsevolod, and Kyurik, the head of the monastery). A similar three-domed cathedral (1117), probably designed by the same masters, stands in the Antoniev Monastery, built on the orders of Antony, the founder of that monastery.

There are now some fifty medieval and early modern churches scattered throughout the city and its surrounding areas. [43] Some of them were blown up by the Nazis and subsequently restored. The most ancient pattern is represented by those dedicated to Saints Pyotr and Pavel (on the Swallow’s Hill, 1185–1192), to Annunciation (in Myachino, 1179), to Assumption (on Volotovo Field, 1180s) and to St. Paraskeva-Piatnitsa (at Yaroslav’s Court, 1207). The greatest masterpiece of early Novgorod architecture is the Savior church at Nereditsa (1198).

In the 13th century, tiny churches of the three-paddled design were in vogue. These are represented by a small chapel at the Peryn Monastery (1230s) and St. Nicholas’ on the Lipnya Islet (1292, also notable for its 14th-century frescoes). The next century saw the development of two original church designs, one of them culminating in St Theodor’s church (1360–1361, fine frescoes from 1380s), and another one leading to the Savior church on Ilyina street (1374, painted in 1378 by Feofan Grek). The Savior’ church in Kovalevo (1345) was originally frescoed by Serbian masters, but the church was destroyed during the war. While the church has since been rebuilt, the frescoes have not been restored.

During the last century of the republican government, some new churches were consecrated to Saints Peter and Paul (on Slavna, 1367; in Kozhevniki, 1406), to Christ’s Nativity (at the Cemetery, 1387), to St. John the Apostle’s (1384), to the Twelve Apostles (1455), to St Demetrius (1467), to St. Simeon (1462), and other saints. Generally, they are not thought[by whom?] to be as innovative as the churches from the previous period. Several shrines from the 12th century (i.e., in Opoki) were demolished brick by brick and then reconstructed exactly as they used to be, several of them in the mid-fifteenth century, again under Archbishop Yevfimy II (Euthymius II), perhaps one of the greatest patrons of architecture in medieval Novgorod.

Novgorod’s conquest by Ivan III in 1478 decisively changed the character of local architecture. Large commissions were thenceforth executed by Muscovite masters and patterned after cathedrals of Moscow Kremlin: e.g., the Savior Cathedral of Khutyn Monastery (1515), the Cathedral of the Mother of God of the Sign (1688), the St. Nicholas Cathedral of Vyaschizhy Monastery (1685). Nevertheless, the styles of some parochial churches were still in keeping with local traditions: e.g., the churches of Myrrh-bearing Women (1510) and of Saints Boris and Gleb (1586).

In Vitoslavlitsy, along the Volkhov River and the Myachino Lake, close to the Yuriev Monastery, a museum of wooden architecture was established in 1964. Over twenty wooden buildings (churches, houses and mills) dating from the 14th to the 19th century were transported there from all around the Novgorod region.

11400 graves of the German 1st Luftwaffe Field Division are found at the war cemetery in Novgorod. Also 1900 soldiers of the Spanish Blue Division are buried there.[44]

-

Walls of the Novgorod Kremlin

-

War Memorial

-

-

Government Building

Transportation[edit]

Intercity transport[edit]

Novgorod main railway station, built in 1953

Novgorod has connections to Moscow (531 km) and St. Petersburg (189 km) by the federal highway M10. There are public buses to Saint Petersburg and other destinations.

The city has direct railway passenger connections with Moscow (Leningradsky Rail Terminal, by night trains), St. Petersburg (Moscow Rail Terminal and Vitebsk Rail Terminal, by suburban trains), Minsk (Belarus) (Minsk Passazhirsky railway station, by night trains) and Murmansk.

The city’s former commercial airport Yurievo was decommissioned in 2006, and the area has now been redeveloped into a residential neighbourhood. The still existing Krechevitsy Airport does not serve any regular flights since mid-1990s although there is a plan to turn Krechevitsy into a new operational airport by 2025.[45] The nearest international airport is St. Petersburg’s Pulkovo, some 180 kilometres (112 miles) north of the city.

Local transportation[edit]

Veliky Novgorod trolleybus map (2021)

Local transportation consists of a network of buses and trolleybuses. The trolleybus network, which currently consists of five routes, started operating in 1995 and is the first trolley system opened in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Honours[edit]

A minor planet, 3799 Novgorod, discovered by the Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1979, is named after the city.[46]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

|

|

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (March 2022) |

Veliky Novgorod is twinned with:[47][48]

Bielefeld, Germany

Kohtla-Järve, Estonia

Moss, Norway

Nanterre, France

Örebro, Sweden