Всего найдено: 30

Привет! У Розенталя сказано следующее: «В текстах, не перегруженных названиями сортов растений, овощей, фруктов и т. д., эти названия заключаются в кавычки и пишутся со строчной буквы, например: помидор «иосиф прекрасный», яблоки «пепин литовский», «бельфлёр-китайка», озимая рожь «ульяновка», георгин «светлана». Общепринятые названия цветов, плодов пишутся со строчной буквы, например: анютины глазки, иван-да-марья, белый налив, антоновка, ренклод, розмарин». Можно ли считать сорт яблок богатырь общепринятым и писать без кавычек?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Поскольку без родового слова яблоня, яблоки этот сорт употребляется редко (нечасто говорят: Я посадил богатырь), то лучше писать с кавычками.

Здравствуйте! Можно писать с прописной буквы Великое княжество (в значении Великое княжество Литовское)?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Можно.

Здравствуйте! Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильно написать названия цветов: акация лорка или Лорка, орех онтарио или Онтарио?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В неспециальных текстах названия сортов растений, овощей, фруктов заключаются в кавычки и пишутся со строчной буквы (в том числе и имена собственные): клубника «виктория»; помидор «иосиф прекрасный»; яблоки «пепин литовский», «бельфлёр китайский», «шафран-китайка».

В специальной литературе в названиях сортов растений, овощей, фруктов, цветов первое слово (и все имена собственные) пишется с прописной буквы: крыжовник Слава Никольска, малина Мальборо, земляника Победитель, смородина Выставочная красная, яблоня Китайка золотая ранняя, слива Никольская белая, роза Мария-Луиза, фиалка Пармская, тюльпан Чёрный принц.

Еще раз здравствуйте. Литовский город Шальчининкай — район какой: Шальчининкайский, Шальчининкский? СМИ и Википедия пишут Шальчининкский. С другой стороны, если район Шальчининкский, то город должен был бы называться Шальчининк(и). Ср.: Друскининкай — Друскининкайский. Что делать? спасибо

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

«Словарь собственных имен русского языка» Ф. Л. Агеенко (М., 2010), адресованный работникам СМИ, фиксирует вариант Шальчининкский. В «Словаре географических названий» Е. А. Левашова (СПб., 2000) – два варианта: Шальчининкский (он отмечен как местный) и Шальчининкайский.

Прочитала справочную информацию, но вопрос все равно остался. Склоняется ли женская фамилия Паукшта (литовские корни, ударение на первый слог)?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мужские и женские фамилии на безударные -а, -я, следующие за согласной буквой, склоняются, ср.: песни Булата Окуджавы, прогнозы Павла Глобы, фильмы Анджея Вайды.

До того, как проводить меня в этот Дом колхозника, зашли сызнова к тебе. В. Распутин, Живи и помни. До того как стать моим интендантом, он прославился храбростью в славном литовском войске. Э. Радзинский, Княжна Тараканова. Почему в первом предложении запятая перед «как» ставится, а во втором предложении не ставится?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

До того как – составной подчинительный союз. Он может целиком входить в придаточную часть (и не разделяться запятой), а может расчленяться, в этом случае запятая ставится между частями союза. Поэтому возможны оба варианта: с запятой и без запятой.

Если говорить о некоторых закономерностях, то можно отметить следующее. Если придаточная часть сложноподчиненного предложения предшествует главной (как в приведенных Вами примерах), составной подчинительный союз чаще не расчленяется. Но и постановка запятой ошибкой не будет.

Здравствуйте! Возник вопрос: с прописной или строчной пишется слово «княжество» в значении Великое княжество литовское? Например: Борьба развернулась не только за территории Княжества.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно написание со строчной буквы.

Уважаемая Справка, в очередной раз задаю вам один и тот же вопрос, так как ответов на мои предыдущие письма вам нет. В свете ваших ответов № 282901, 272430, 263616, 263602, 254952, какие буквы (прописные или строчные) нужно использовать в официальных названиях исторических государств, закончивших своё существование в результате Первой мировой войны и её последствий? Примеры: Украинская Народная Республика или Украинская народная республика? Украинская Держава или Украинская держава? Донецко-Криворожская Советская Республика или Донецко-Криворожская советская республика? Литовско-Белорусская Советская Социалистическая Республика или Литовско-Белорусская советская социалистическая республика? Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мы ответили Вам. См. ответ на вопрос № 284608.

Как писать названия государств или территорий периода начала прошлого века типа: Кубанская народная республика, Литовско-Белорусская советская социалистическая республика и т. п.? Вроде бы они уже столетие как не существуют, и надо писать всё со строчной кроме первого слова, но с другой стороны есть аналоги типа Украинская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Болгарская Народная Республика, которых тоже уже нет, только не столетие, а пару десятилетий.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Непростой вопрос. С одной стороны, в исторических (не существующих в настоящее время) названиях государств с большой буквы пишутся первое слово и входящие в состав названия имена собственные: Французское королевство, Неаполитанское королевство, Королевство обеих Сицилий; Римская империя, Византийская империя, Российская империя; Новгородская республика, Венецианская республика; Древнерусское государство, Великое государство Ляо и т. д.

С другой стороны, в названии Союз Советских Социалистических Республик все слова пишутся с большой буквы, хотя этого государства тоже уже не существует. Сохраняются прописные буквы и в названиях союзных республик, в исторических названиях стран соцлагеря: Польская Народная Республика, Народная Республика Болгария и т. д.

Историческая дистанция, безусловно, является здесь одним из ключевых факторов. Должно пройти какое-то время (не два–три десятилетия, а гораздо больше), для того чтобы появились основания писать Союз советских социалистических республик по аналогии с Российская империя.

Историческая дистанция вроде бы позволяет писать в приведенных Вами названиях государственных образований с большой буквы только первое слово (эти образования существовали непродолжительное время и исчезли уже почти 100 лет назад). Но, с другой стороны, прописная буква в каждом слове названия подчеркивает тот факт, что эти сочетания в свое время были официальными названиями государств (или претендовали на такой статус). Если автору текста важно обратить на это внимания читателя, он вправе оставить прописные буквы (даже несмотря на то, что таких государственных образований давно уже нет на карте).

Здравствуйте! Как правильно писать: эстоноязычный или эстонскоязычный, литовоязычный или литовскоязычный, латышеязычный или латышскоязычный, узбекоязычный или узбекскоязычный, киргизоязычный или киргизскоязычный и т.д.? Или возможны различные варианты? С уважением, Андрей

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

У прилагательных такого типа обычно выбирается вариант с усеченной (бессуфиксальной) первой основой (если он есть). Так, «Русский орфографический словарь» РАН (4-е изд. М., 2012) фиксирует: испаноязычный (не испанско-), украиноязычный (не украинско-), англоязычный и т. д. Но: русскоязычный (нет варианта с усеченной основой). Поэтому корректно: эстоноязычный, узбекоязычный, киргизоязычный. Но: латышскоязычный (нет варианта с усеченной основой).

Как правильно будет писаться название литовского сыра «Džiugas» по-русски — джЮгас или джУгас? Гугл при запросе предлагает джЮгас. Но вообще в интернете пишут кто как хочет

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Согласно «Инструкции по транскрипции фамилий, имён и географических названий с русского языка на литовский язык и с литовского языка на русский язык» (Вильнюс, 1990), буквенное сочетание iu в литовских именах собственных передается на русский язык буквой ю. Правильно: «Джюгас».

Склоняется ли литовская мужская фамилия Венцюс в русском языке? Если да, то каое правило.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мужская фамилия Венцюс склоняется, женская – нет. Законы русской грамматики требуют склонения всех мужских фамилий, оканчивающихся на согласный, независимо от их языкового происхождения. Единственное исключение – фамилии на —ых, -их типа Черных, Долгих.

Здравствуйте! Подскажите, какправильно поставить ударение в имени литовского князя Миндовга? Дети спросили на уроке, и мы не смогли найти информацию в интернете.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Ударение на первом слоге: Миндовг. См.: Агеенко Ф. Л. Словарь собственных имен русского языка. М., 2010.

Здравствуйте! Скажите, пожалуйста, названия государств, в которых присутствует слово острова, пишутся все слова с прописной буквы для всех случаев? В последнее время часто встречается написание Великое Княжество Литовское с прописной буквы (княжество). Исторически и зафиксировано в старых словарях Великое княжество Литовское. Как правильно? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В новых словарях тоже зафиксировано Великое княжество Литовское (например, в 4-м издании «Русского орфографического словаря», вышедшем в 2012 году). Т. е. орфографическая норма не менялась, написание слова княжество в этом сочетании с большой буквы нарушает норму. Княжество пишется с прописной только в официальных названиях современных государств (Княжество Монако).

Слово Острова пишется с прописной в официальных названиях государств, административных территорий: Республика Маршалловы Острова. В значении ‘группа островов, архипелаг’ слово острова пишется строчными: Маршалловы острова (архипелаг).

Здравствуйте!

Я уже задавал этот вопрос, но, кажется, он не был отправлен на сайт.

Склоняется ли литовская мужская фамилия Станкевичус?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, эта мужская фамилия склоняется (женская несклоняема).

|

Grand Duchy of Lithuania |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1236–17951 | ||||||||||||

|

Supposed appearance of the royal (military) banner with design derived from a 16th century coat of arms[1][2] Coat of arms |

||||||||||||

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the height of its power in the 15th century with claimed territory shown in light green |

||||||||||||

| Status |

|

|||||||||||

| Capital |

|

|||||||||||

| Common languages | Lithuanian, Ruthenian, Polish, Latin, German, Yiddish, Tatar, Karaim (see § Languages) | |||||||||||

| Religion |

|

|||||||||||

| Government |

|

|||||||||||

| Grand Duke | ||||||||||||

|

• 1236–1263 (from 1251 as King) |

Mindaugas (first) | |||||||||||

|

• 1764–1795 |

Stanisław August Poniatowski (last) | |||||||||||

| Legislature | Seimas | |||||||||||

|

• Privy Council |

Council of Lords | |||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||

|

• Consolidation began |

1180s | |||||||||||

|

• Kingdom of Lithuania |

1251–1263 | |||||||||||

|

• Union of Krewo |

14 August 1385 | |||||||||||

|

• Union of Lublin |

1 July 1569 | |||||||||||

|

• Third Partition |

24 October 1795 | |||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||

| 1260[3] | 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| 1430[3] | 930,000 km2 (360,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| 1572[3] | 320,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| 1791[3] | 250,000 km2 (97,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| 1793[3] | 132,000 km2 (51,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||

|

• 1260[3] |

400,000 | |||||||||||

|

• 1430[3] |

2,500,000 | |||||||||||

|

• 1572[3] |

1,700,000 | |||||||||||

|

• 1791[3] |

2,500,000 | |||||||||||

|

• 1793[3] |

1,800,000 | |||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

1. Unsuccessful Constitution of 3 May 1791 envisioned a unitary state whereby the Grand Duchy would be abolished, however an addendum to the Constitution, known as the Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations, restored Lithuania on 20 October 1791.[4] |

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century[5] to 1795,[6] when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Lithuanians, who were at the time a polytheistic nation born from several united Baltic tribes from Aukštaitija.[7][8][9]

The Grand Duchy expanded to include large portions of the former Kievan Rus’ and other neighbouring states, including what is now Lithuania, Belarus and parts of Ukraine, Latvia, Poland, Russia and Moldova. At its greatest extent, in the 15th century, it was the largest state in Europe.[10] It was a multi-ethnic and multiconfessional state, with great diversity in languages, religion, and cultural heritage.

The consolidation of the Lithuanian lands began in the late 13th century. Mindaugas, the first ruler of the Grand Duchy, was crowned as Catholic King of Lithuania in 1253. The pagan state was targeted in a religious crusade by the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Order, but survived. Its rapid territorial expansion started late in the reign of Gediminas,[11] and continued under the diarchy and co-leadership of his sons Algirdas and Kęstutis.[12] Algirdas’s son Jogaila signed the Union of Krewo in 1386, bringing two major changes in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: conversion to Christianity of Europe’s last pagan state,[13] and establishment of a dynastic union between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland.[14]

The reign of Vytautas the Great, son of Kęstutis, marked both the greatest territorial expansion of the Grand Duchy and the defeat of the Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. It also marked the rise of the Lithuanian nobility. After Vytautas’s death, Lithuania’s relationship with the Kingdom of Poland greatly deteriorated.[15] Lithuanian noblemen, including the Radvila family, attempted to break the personal union with Poland.[16] However, unsuccessful wars with the Grand Duchy of Moscow forced the union to remain intact.

Eventually, the Union of Lublin of 1569 created a new state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the Federation, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania maintained its political distinctiveness and had separate ministries, laws, army, and treasury.[17] The federation was terminated by the passing of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, when it was supposed to become a single country, the Commonwealth, under one monarch, one parliament and no Lithuanian autonomy. Shortly afterward, the unitary character of the state was confirmed by adopting the Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations.

However, the newly reformed Commonwealth was invaded by Russia in 1792 and partitioned between neighbouring states. A truncated state (whose principal cities were Kraków, Warsaw and Vilnius) remained that was nominally independent. After the Kościuszko Uprising, the territory was completely partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and Austria in 1795.

Etymology[edit]

The name of Lithuania (Litua) was first mentioned in 1009 in Annals of Quedlinburg. Some older etymological theories relate the name to a small river not far from Kernavė, the core area of the early Lithuanian state and a possible first capital of the would-be Grand Duchy of Lithuania, is usually credited as the source of the name. This river’s original name is Lietava.[18] As time passed, the suffix —ava could have changed into —uva, as the two are from the same suffix branch. The river flows in the lowlands and easily spills over its banks, therefore the traditional Lithuanian form liet— could be directly translated as lietis (to spill), of the root derived from the Proto-Indo-European leyǝ-.[19] However, the river is very small and some find it improbable that such a small and local object could have lent its name to an entire nation. On the other hand, such a fact is not unprecedented in world history.[20] The most credible modern theory of etymology of the name of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuva) is Artūras Dubonis’s hypothesis,[21] that Lietuva relates to the word leičiai (plural of leitis, a social group of warriors-knights in the early Grand Duchy of Lithuania). The title of the Grand Duchy was consistently applied to Lithuania from the 14th century onward.[22]

In other languages, the grand duchy is referred to as:

- Belarusian: Вялікае Княства Літоўскае

- German: Großfürstentum Litauen

- Estonian: Leedu Suurvürstiriik

- Latin: Magnus Ducatus Lituaniæ

- Latvian: Lieitija or Lietuvas Lielkņaziste

- Lithuanian: Lietuvos Didžioji Kunigaikštystė

- Old literary Lithuanian: Didi Kunigystė Lietuvos (didi Kunigiſte Lietuwos[23])

- Polish: Wielkie Księstwo Litewskie

- Romanian: Marele Ducat al Lituaniei

- Russian: Великое княжество Литовское

- Ruthenian: Великое кнѧзство Литовское

- Ukrainian: Велике князiвство Литовське

Naming convention of both title of ruler (hospodar)[24] and the state changed as it expanded its territory. Following the decline of the Kingdom of Ruthenia[25] and incorporation of its lands into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Gediminas started to title himself as «King of Lithuanians and many Ruthenians»,[26][27][28] while the name of the state became the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Ruthenia.[29][30] Similarly the title changed to «King of Lithuanians and Ruthenians, ruler and duke of Semigallia» when Semigallia became part of the state.[31][32] The 1529 edition of the Statute of Lithuania described the titles of Sigismund I the Old as «King of Poland, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Ruthenia, Prussia, Samogitia, Mazovia, and other [ lands ]».[33] When southern and western Ruthenian lands were transferred to the Crown after the Union of Lublin, the titles of the Grand Duke of Lithuania were transferred to the titles of the rulers of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[citation needed]

The country was also called the Republic of Lithuania (Latin: Respublica Lituana) since at least the mid-16th century, already before the Union of Lublin in 1569.[34]

History[edit]

Establishment of the state[edit]

Balts in the 12th century

The first written reference to Lithuania is found in the Quedlinburg Chronicle, which dates from 1009.[35] In the 12th century, Slavic chronicles refer to Lithuania as one of the areas attacked by the Rus’. Pagan Lithuanians initially paid tribute to Polotsk, but they soon grew in strength and organized their own small-scale raids. At some point between 1180 and 1183 the situation began to change, and the Lithuanians started to organize sustainable military raids on the Slavic provinces, raiding the Principality of Polotsk as well as Pskov, and even threatening Novgorod.[36] The sudden spark of military raids marked consolidation of the Lithuanian lands in Aukštaitija.[5] The Lithuanians are the only branch within the Baltic group that managed to create a state entity in premodern times.[37]

The Lithuanian Crusade began after the Livonian Order and Teutonic Knights, crusading military orders, were established in Riga and in Prussia in 1202 and 1226 respectively. The Christian orders posed a significant threat to pagan Baltic tribes, and further galvanized the formation of the Lithuanian state. The peace treaty with Galicia–Volhynia of 1219 provides evidence of cooperation between Lithuanians and Samogitians. This treaty lists 21 Lithuanian dukes, including five senior Lithuanian dukes from Aukštaitija (Živinbudas, Daujotas, Vilikaila, Dausprungas and Mindaugas) and several dukes from Žemaitija. Although they had battled in the past, the Lithuanians and the Žemaičiai now faced a common enemy.[38] Likely Živinbudas had the most authority[36] and at least several dukes were from the same families.[39] The formal acknowledgement of common interests and the establishment of a hierarchy among the signatories of the treaty foreshadowed the emergence of the state.[40]

Kingdom of Lithuania[edit]

Mindaugas, the duke[41] of southern Lithuania,[42] was among the five senior dukes mentioned in the treaty with Galicia–Volhynia. The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, reports that by the mid-1230s, Mindaugas had acquired supreme power in the whole of Lithuania.[43] In 1236, the Samogitians, led by Vykintas, defeated the Livonian Order in the Battle of Saule.[44] The Order was forced to become a branch of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia, making Samogitia, a strip of land that separated Livonia from Prussia, the main target of both orders. The battle provided a break in the wars with the Knights, and Lithuania exploited this situation, arranging attacks on the Ruthenian provinces and annexing Navahrudak and Hrodna.[43]

In 1248, a civil war broke out between Mindaugas and his nephews Tautvilas and Edivydas. The powerful coalition against Mindaugas included Vykintas, the Livonian Order, Daniel of Galicia and Vasilko of Volhynia. Taking advantage of internal conflicts, Mindaugas allied with the Livonian Order. He promised to convert to Christianity and exchange some lands in western Lithuania in return for military assistance against his nephews and the royal crown. In 1251, Mindaugas was baptized and Pope Innocent IV issued a papal bull proclaiming the creation of the Kingdom of Lithuania. After the civil war ended, Mindaugas was crowned as King of Lithuania on 6 July 1253, starting a decade of relative peace. Mindaugas later renounced Christianity and converted back to paganism. Mindaugas tried to expand his influence in Polatsk, a major centre of commerce in the Daugava River basin, and Pinsk.[43] The Teutonic Knights used this period to strengthen their position in parts of Samogitia and Livonia, but they lost the Battle of Skuodas in 1259 and the Battle of Durbe in 1260.[45] This encouraged the conquered Semigallians and Old Prussians to rebel against the Knights.[46]

Encouraged by Treniota, Mindaugas broke the peace with the Order, possibly reverted to pagan beliefs. He hoped to unite all Baltic tribes under the Lithuanian leadership. As military campaigns were not successful, the relationships between Mindaugas and Treniota deteriorated. Treniota, together with Daumantas of Pskov, assassinated Mindaugas and his two sons, Ruklys and Rupeikis, in 1263.[47] The state lapsed into years of internal fighting.[48]

Rise of the Gediminids[edit]

From 1263 to 1269, Lithuania had three grand dukes – Treniota, Vaišvilkas, and Švarnas. The state did not disintegrate, however, and Traidenis came to power in 1269. He strengthened Lithuanian control in Black Ruthenia and fought with the Livonian Order, winning the Battle of Karuse in 1270 and the Battle of Aizkraukle in 1279. There is considerable uncertainty about the identities of the grand dukes of Lithuania between his death in 1282 and the assumption of power by Vytenis in 1295. During this time the Orders finalized their conquests. In 1274, the Great Prussian Rebellion ended, and the Teutonic Knights proceeded to conquer other Baltic tribes: the Nadruvians and Skalvians in 1274–1277, and the Yotvingians in 1283; the Livonian Order completed its conquest of Semigalia, the last Baltic ally of Lithuania, in 1291.[49] The Orders could now turn their full attention to Lithuania. The «buffer zone» composed of other Baltic tribes had disappeared, and Grand Duchy of Lithuania was left to battle the Orders on its own.[50]

The Gediminid dynasty ruled the grand duchy for over a century, and Vytenis was the first ruler of the dynasty.[51] During his reign Lithuania was in constant war with the Order, the Kingdom of Poland, and Ruthenia. Vytenis was involved in succession disputes in Poland, supporting Boleslaus II of Masovia, who was married to a Lithuanian duchess, Gaudemunda. In Ruthenia, Vytenis managed to recapture lands lost after the assassination of Mindaugas and to capture the principalities of Pinsk [lt] and Turov. In the struggle against the Order, Vytenis allied with Riga’s citizens; securing positions in Riga strengthened trade routes and provided a base for further military campaigns. Around 1307, Polotsk, an important trading centre, was annexed by military force.[52] Vytenis also began constructing a defensive castle network along Nemunas.[53] Gradually this network developed into the main defensive line against the Teutonic Order.[53]

Lithuanian state in 13–15th centuries

Territorial expansion[edit]

The expansion of the state reached its height under Grand Duke Gediminas, also titled by some contemporaneous German sources as Rex de Owsteiten (English: King of Aukštaitija),[54] who created a strong central government and established an empire that later spread from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea.[55][56] In 1320, most of the principalities of western Rus’ were either vassalized or annexed by Lithuania. In 1321, Gediminas captured Kiev, sending Stanislav, the last Rurikid to rule Kiev, into exile. Gediminas also re-established the permanent capital of the Grand Duchy in Vilnius,[57] presumably moving it from Old Trakai in 1323.[58] The state continued to expand its territory under the reign of Grand Duke Algirdas and his brother Kęstutis, who both ruled the state harmonically.[59][60]

Lithuania was in a good position to conquer the western and the southern parts of former Kievan Rus’. While almost every other state around it had been plundered or defeated by the Mongols, the hordes stopped at the modern borders of Belarus, and the core territory of the Grand Duchy was left mostly untouched. The weak control of the Mongols over the areas they had conquered allowed the expansion of Lithuania to accelerate. Rus’ principalities were never incorporated directly into the Golden Horde, maintaining vassal relationships with a fair degree of independence. Lithuania annexed some of these areas as vassals through diplomacy, as they exchanged rule by the Mongols or the Grand Prince of Moscow with rule by the Grand Duchy. An example is Novgorod, which was often in the Lithuanian sphere of influence and became an occasional dependency of the Grand Duchy.[61] Lithuanian control resulted from internal frictions within the city, which attempted to escape submission to Moscow. Such relationships could be tenuous, however, as changes in a city’s internal politics could disrupt Lithuanian control, as happened on a number of occasions with Novgorod and other East-Slavic cities.[citation needed]

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania managed to hold off Mongol incursions and eventually secured gains. In 1333 and 1339, Lithuanians defeated large Mongol forces attempting to regain Smolensk from the Lithuanian sphere of influence. By about 1355, the State of Moldavia had formed, and the Golden Horde did little to re-vassalize the area. In 1362, regiments of the Grand Duchy army defeated the Golden Horde at the Battle at Blue Waters.[62] In 1380, a Lithuanian army allied with Russian forces to defeat the Golden Horde in the Battle of Kulikovo, and though the rule of the Mongols did not end, their influence in the region waned thereafter. In 1387, Moldavia became a vassal of Poland and, in a broader sense, of Lithuania. By this time, Lithuania had conquered the territory of the Golden Horde all the way to the Dnieper River. In a crusade against the Golden Horde in 1398 (in an alliance with Tokhtamysh), Lithuania invaded northern Crimea and won a decisive victory. In an attempt to place Tokhtamish on the Golden Horde throne in 1399, Lithuania moved against the Horde but was defeated in the Battle of the Vorskla River, losing the steppe region.[63]

Grand Duchy of Lithuania under the rule of Vytautas the Great

Personal Union with Poland[edit]

Lithuania was Christianized in 1387, led by Jogaila, who personally translated Christian prayers into the Lithuanian language[64] and his cousin Vytautas the Great who founded many Catholic churches and allocated lands for parishes in Lithuania. The state reached a peak under Vytautas the Great, who reigned from 1392 to 1430. Vytautas was one of the most famous rulers of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, serving as the Grand Duke from 1401 to 1430, and as the Prince of Hrodna (1370–1382) and the Prince of Lutsk (1387–1389). Vytautas was the son of Kęstutis, uncle of Jogaila, who became King of Poland in 1386, and he was the grandfather of Vasili II of Moscow.[65]

In 1410, Vytautas commanded the forces of the Grand Duchy in the Battle of Grunwald. The battle ended in a decisive Polish-Lithuanian victory against the Teutonic Order. The war of Lithuania against military Orders, which lasted for more than 200 years, and was one of the longest wars in the history of Europe, was finally ended. Vytautas backed the economic development of the state and introduced many reforms. Under his rule, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania slowly became more centralized, as the governours loyal to Vytautas replaced local princes with dynastic ties to the throne. The governours were rich landowners who formed the basis for the nobility of the Grand Duchy. During Vytautas’ rule, the Radziwiłł and Goštautas families started to gain influence.[66][67]

The rapid expansion of the influence of Moscow soon put it into a comparable position to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and after the annexation of Novgorod in 1478, Muscovy was among the preeminent states in northeastern Europe. Between 1492 and 1508, Ivan III further consolidated Muscovy, winning the key Battle of Vedrosha and regaining such ancient lands of Kievan Rus’ as Chernihiv and Bryansk.[68]

On 8 September 1514, the allied forces of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, under the command of Hetman Konstanty Ostrogski, fought the Battle of Orsha against the army of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, under Konyushy Ivan Chelyadnin and Kniaz Mikhail Golitsin. The battle was part of a long series of Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars conducted by Russian rulers striving to gather all the former lands of Kievan Rus’ under their rule. According to Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii by Sigismund von Herberstein, the primary source for the information on the battle, the much smaller army of Poland–Lithuania (under 30,000 men) defeated the 80,000 Muscovite soldiers, capturing their camp and commander. The Muscovites lost about 30,000 men, while the losses of the Poland–Lithuania army totalled only 500. While the battle is remembered as one of the greatest Lithuanian victories, Muscovy ultimately prevailed in the war. Under the 1522 peace treaty, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania made large territorial concessions.[69]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth[edit]

The wars with the Teutonic Order, the loss of land to Moscow, and the continued pressure threatened the survival of the state of Lithuania, so it was forced to ally more closely with Poland, uniting with its western neighbour as the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (Commonwealth of Two Nations) in the Union of Lublin of 1569. During the period of the Union, many of the territories formerly controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were transferred to the Crown of the Polish Kingdom, while the gradual process of Polonization slowly drew Lithuania itself under Polish domination.[70][71][72] The Grand Duchy retained many rights in the federation (including separate ministries, laws, army, and treasury) until the May Constitution of Poland and Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations were passed in 1791.[73]

Partitions and the Napoleonic period[edit]

Following the partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, most of the lands of the former Grand Duchy were directly annexed by the Russian Empire, the rest by Prussia. In 1812, just prior to the French invasion of Russia, the former Grand Duchy revolted against the Russians. Soon after his arrival in Vilnius, Napoleon proclaimed the creation of a Commissary Provisional Government of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania which, in turn, renewed the Polish-Lithuanian Union.[74] The union was never formalized, however, as only half a year later Napoleon’s Grande Armée was pushed out of Russia and forced to retreat further westwards. In December 1812, Vilnius was recaptured by Russian forces, bringing all plans of recreation of the Grand Duchy to an end.[74] Most of the lands of the former Grand Duchy were re-annexed by Russia. The Augustów Voivodeship (later Augustów Governorate), including the counties of Marijampolė and Kalvarija, was attached to the Kingdom of Poland, a rump state in personal union with Russia.[citation needed]

Administrative division[edit]

Lithuania and its administrative divisions in the 17th century

Administrative structure of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (1413–1564).[75]

| Voivodeship (Palatinatus) | Established |

|---|---|

| Vilnius | 1413 |

| Trakai | 1413 |

| Samogitian eldership | 1413 |

| Kiev | 1471 |

| Polotsk | 1504 |

| Naugardukas | 1507 |

| Smolensk | 1508 |

| Vitebsk | 1511 |

| Podlaskie | 1514 |

| Brest Litovsk | 1566 |

| Minsk | 1566 |

| Mstislavl | 1569 |

| Volhyn | 1564–1566 |

| Bratslav | 1564 |

| Duchy of Livonia | 1561 |

Religion and culture[edit]

Christianity and paganism[edit]

After the baptism in 1252 and coronation of King Mindaugas in 1253, Lithuania was recognized as a Christian state until 1260, when Mindaugas supported an uprising in Courland and (according to the German order) renounced Christianity. Up until 1387, Lithuanian nobles professed their own religion, which was polytheistic.[77] Ethnic Lithuanians were very dedicated to their faith. The pagan beliefs needed to be deeply entrenched to survive strong pressure from missionaries and foreign powers. Until the 17th century, there were relics of old faith reported by counter-reformation active Jesuit priests, like feeding žaltys with milk or bringing food to graves of ancestors. The lands of modern-day Belarus and Ukraine, as well as local dukes (princes) in these regions, were firmly Orthodox Christian (Greek Catholic after the Union of Brest), though. While pagan beliefs in Lithuania were strong enough to survive centuries of pressure from military orders and missionaries, they did eventually succumb. A separate Eastern Orthodox metropolitan eparchy was created sometime between 1315 and 1317 by the Constantinople Patriarch John XIII. Following the Galicia–Volhynia Wars which divided the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, in 1355 the Halych metropoly was liquidated and its eparchies transferred to the metropoles of Lithuania and Volhynia.[78]

In 1387, Lithuania converted to Catholicism, while most of the Ruthenian lands stayed Orthodox, however, on 22 February 1387, Supreme Duke Jogaila banned Catholics marriages with Orthodox, and demanded those Orthodox who previously married with the Catholics to convert to Catholicism.[79] At one point, though, Pope Alexander VI reprimanded the Grand Duke for keeping non-Catholics as advisers.[80] Consequently, only in 1563 did Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus issue a privilege that equalized the rights of Orthodox and Catholics in Lithuania and abolished all previous restrictions on Orthodox.[81] There was an effort to polarise Orthodox Christians after the Union of Brest in 1596, by which some Orthodox Christians acknowledged papal authority and Catholic catechism, but preserved their liturgy. The country also became one of the major centres of the Reformation.[82]

In the second half of the 16th century, Calvinism spread in Lithuania, supported by the families of Radziwiłł, Chodkiewicz, Sapieha, Dorohostajski and others. By the 1580s the majority of the senators from Lithuania were Calvinist or Socinian Unitarians (Jan Kiszka).[83]

In 1579, Stephen Báthory, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, founded Vilnius University, one of the oldest universities in Northern Europe. Due to the work of the Jesuits during the Counter-Reformation the university soon developed into one of the most important scientific and cultural centres of the region and the most notable scientific centre of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[84] The work of the Jesuits as well as conversions from among the Lithuanian senatorial families turned the tide and by the 1670s Calvinism lost its former importance though it still retained some influence among the ethnically Lithuanian peasants and some middle nobility.[citation needed]

Islam[edit]

Islam in Lithuania, unlike many other northern and western European countries, has a long history starting from 14th century.[85] Small groups of Muslim Lipka Tatars migrated to ethnically Lithuanian lands, mainly under the rule of Grand Duke Vytautas (early 15th century). In Lithuania, unlike many other European societies at the time, there was religious freedom. Lithuanian Tatars were allowed to settle in certain places, such as Trakai and Kaunas.[86] Keturiasdešimt Totorių is one of the oldest Tatar settlements in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. After a successful military campaign of the Crimean Peninsula in 1397, Vytautas brought the first Crimean Tatar prisoners of war to Trakai and various places in the Duchy of Trakai, including localities near Vokė river just south of Vilnius. The first mosque in this village was mentioned for the first time in 1558. There were 42 Tatar families in the village in 1630.[87]

Judaism[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2022) |

Languages[edit]

In the 13th century, the centre of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was inhabited by a majority that spoke Lithuanian,[88] though it was not a written language until the 16th century.[89] In the other parts of the duchy, the majority of the population, including Ruthenian nobles and ordinary people, used both spoken and written Ruthenian.[88] Nobles who migrated from one place to another would adapt to a new locality and adopt the local religion and culture and those Lithuanian noble families that moved to Slavic areas often took up the local culture quickly over subsequent generations.[90] Ruthenians were native to the east-central and south-eastern parts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[citation needed]

Ruthenian, also called Chancery Slavonic in its written form, was used to write laws alongside Polish, Latin and German, but its use varied between regions. From the time of Vytautas, there are fewer remaining documents written in Ruthenian than there are in Latin and German, but later Ruthenian became the main language of documentation and writings, especially in eastern and southern parts of the Duchy. In the 16th century at the time of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Lithuanian lands became partially polonized over time and started to use Polish for writing much more often than the Lithuanian and Ruthenian languages. Polish finally became the official chancellery language of the Commonwealth in 1697.[90][91][92][93]

The voivodeships with a predominantly ethnic Lithuanian population, Vilnius, Trakai, and Samogitian voivodeships, remained almost wholly Lithuanian-speaking, both colloquially and by ruling nobility.[94] Ruthenian communities were also present in the extreme southern parts of Trakai voivodeship and south-eastern parts of Vilnius Voivodeship. In addition to Lithuanians and Ruthenians, other important ethnic groups throughout the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were Jews and Tatars.[90]

Languages for state and academic purposes[edit]

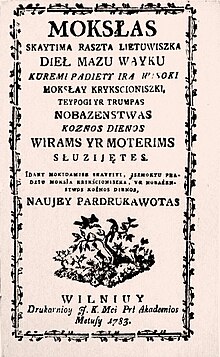

Lithuanian primer for kids, published in Vilnius, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 1783 edition

Numerous languages were used in state documents depending on which period in history and for what purpose. These languages included Lithuanian, Ruthenian,[93][95] Polish and, to a lesser extent (mostly in early diplomatic communication), Latin and German.[89][90][92]

The Court used Ruthenian to correspond with Eastern countries while Latin and German were used in foreign affairs with Western countries.[93][96] During the latter part of the history of the Grand Duchy, Polish was increasingly used in State documents, especially after the Union of Lublin.[92] By 1697, Polish had largely replaced Ruthenian as the «official» language at Court,[89][93][97] although Ruthenian continued to be used on a few official documents until the second half of the 18th century.[91]

It is known that Jogaila, being ethnic Lithuanian by the man’s line, himself knew and spoke in the Lithuanian language with Vytautas the Great, his cousin from the Gediminids dynasty.[98][99][100] Also, during the Christianization of Samogitia, none of the clergy, who came to Samogitia with Jogaila, were able to communicate with the natives, therefore Jogaila himself taught the Samogitians about the Catholicism, thus he was able to communicate in the Samogitian dialect of the Lithuanian language.[101] Use of Lithuanian still continued at the Court after the death of Vytautas and Jogaila.[102] Since the young Grand Duke Casimir IV Jagiellon was underage, the supreme control over the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was in the hands of the Lithuanian Council of Lords, presided by Jonas Goštautas, while Casimir was taught Lithuanian language and the customs of Lithuania by appointed court officials.[103][104] Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon also could understand and speak Lithuanian.[102] While Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus maintained both Polish-speaking and Lithuanian-speaking courts.[102]

From the beginning of the 16th century, and especially after a rebellion led by Michael Glinski in 1508, there were attempts by the Court to replace the usage of Ruthenian with Latin.[105] The use of Ruthenian by academics in areas formerly part of Rus’ and even in Lithuania proper was widespread. Court Chancellor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Lew Sapieha noted in the preface of the Third Statute of Lithuania (1588) that all state documents to be written exclusively in Ruthenian. The same was stated in part 4 of the Statute:

And clerk must use Ruthenian letters and Ruthenian words in all pages, letters and requests, and not any other language or words…

— А писаръ земъский маеть по-руску литерами и словы рускими вси листы, выписы и позвы писати, а не иншимъ езыкомъ и словы…, The Statute of GDL 1588. Part 4, article 1[106]

Despite that, Polish-language editions stated the same in Polish.[107] Statutes of the Grand Duchy were translated into Latin and Polish. One of the main reasons for translations into Latin was that Ruthenian had no well defined and codified law concepts and definitions, which caused many disputes in courts. Another reason to use Latin was a popular idea that Lithuanians were descendants of Romans – the mythical house of Palemonids. Augustinus Rotundus translated the Second Statute into Latin.[108]

According to scientist Rita Regina Trimonienė, the Lithuanians surnames are not slavified and are written as they were pronounced by parishioners in the registers of baptism of Šiauliai Church (dated in the 17th century).[109]

In 1552, Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus ordered that orders of the Magistrate of Vilnius be announced in Lithuanian, Polish, and Ruthenian.[110] The same requirement was valid for the Magistrate of Kaunas.[111][112]

Mikalojus Daukša, writing in the introduction to his Postil (1599) (which was written in Lithuanian) in Polish, advocated the promotion of Lithuanian in the Grand Duchy, noting in the introduction that many people, especially szlachta, preferred to speak Polish rather than Lithuanian, but spoke Polish poorly.[citation needed] Such were the linguistic trends in the Grand Duchy that, by the political reforms of 1564–1566, parliaments, local land courts, appellate courts and other State functions were recorded in Polish,[105] and Polish became increasingly spoken across all social classes.[citation needed]

Lithuanian language situation[edit]

«We do not know on whose merits or guilt such a decision was made, or with what we have offended Your Lordship so much that Your Lordship has deservedly been directed against us, creating hardship for us everywhere. First of all, you made and announced a decision about the land of Samogitia, which is our inheritance and our homeland from the legal succession of the ancestors and elders. We still own it, it is and has always been the same Lithuanian land, because there is one language and the same inhabitants. But since the land of Samogitia is located lower than the land of Lithuania, it is called Samogitia, because in Lithuanian it is called lower land [ Žemaitija ]. And the Samogitians call Lithuania Aukštaitija, that is, from the Samogitian point of view, a higher land. Also, the people of Samogitia have long called themselves Lithuanians and never Samogitians, and because of such identity (sic) we do not write about Samogitia in our letter, because everything is one: one country and the same inhabitants.»

— Vytautas the Great, excerpt from his 11 March 1420 Latin letter sent to Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, in which he described the core of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, composed from Žemaitija (lowlands) and Aukštaitija (highlands), and its language.[113][114] The term Aukštaitija has been known since the 13th century.[115]

Area where Lithuanian was spoken in the 16th century

Lithuania proper (in green) and Samogitia (in red) within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in a map from 1712

Ruthenian and Polish were used as state languages of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, besides Latin and German in diplomatic correspondence. However, Lithuanian was dominant in parts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania like Samogitia, where the local nobility’s reliance on Lithuanian resulted in Stanislovas Radvila remarking in a letter to his brother Mikalojus Kristupas Radvila Našlaitėlis immediately after becoming the Elder of Samogitia that: «While learning various languages, I forgot Lithuanian, and now I see, I have to go to school again, because that language, as I see, God willing, will be needed.»[116] Vilnius, Trakai and Samogitia were the core voivodeships of the state, being part of Lithuania Proper, as evidenced by the privileged position of their governors in state authorities, such as the Council of Lords. Peasants in ethnic Lithuanian territories spoke exclusively Lithuanian, except in transitional border regions, but the Statutes of Lithuania and other laws and documentation were written in Ruthenian, Latin and Polish. Following the example of the royal court, there was a tendency to replace Lithuanian with Polish in the ethnic Lithuanian areas, whereas Ruthenian was stronger in ethnic Belarusian and Ukrainian territories. A note written by Sigismund von Herberstein’s states that, in an ocean of Ruthenian in this part of Europe, there were two non-Ruthenian regions: Lithuania and Samogitia.[105]

Panegyric to Sigismund III Vasa, visiting Vilnius, first hexameter in Lithuanian, 1589

Since the founding of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the higher strata of Lithuanian society from ethnic Lithuania spoke Lithuanian, although from the later 16th century gradually began using Polish, and those from Ruthenia – Ruthenian. Samogitia was unique because of its economic situation – it lay near sea ports and there were fewer people under corvee, instead of that, many commoners were taxpayers.[clarification needed] As a result, the stratification of society was not as sharp as in other areas. Being more similar to a commoner population, the local szlachta spoke Lithuanian to a bigger extent than in the areas close to the capital Vilnius, which itself had become the starting point of intensive linguistic Polonization of the surrounding areas since the 18th century.[citation needed]

In Vilnius University, there are preserved texts written in the Lithuanian language of the Vilnius area, a dialect of Eastern Aukštaitian, which was spoken in a territory located south-eastwards from Vilnius. The sources are preserved in works of graduates from Stanislovas Rapolionis-based Lithuanian language schools, graduate Martynas Mažvydas and Rapalionis relative Abraomas Kulvietis.[117][118]

One of the main sources of Lithuanian written in the Eastern Aukštaitian dialect (Vilnius dialect) was preserved by Konstantinas Sirvydas in a trilingual (Polish-Latin-Lithuanian) 17th-century dictionary, Dictionarium trium linguarum in usum studiosæ juventutis, which was the main Lithuanian dictionary used until the late 19th century.[119][120]

Universitas lingvarum Litvaniæ, published in Vilnius, 1737, is the oldest surviving grammar of the Lithuanian language published in the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[121]

Demographics[edit]

«This is the peace made by the Livonian Master and the King of Lithuania and expressed in the following words:

(…) Next, a German merchant can travel safely concerning his life and property through Rus’ [ Ruthenia ] and Lithuania as far as the King of Lithuania’s authority seeks.

(…) Next, if something is stolen from a German merchant in Lithuania or Rus’, it must be put on trial where it happens; if it happens that a German steals from a Rus [ Ruthenian ] or a Lithuanian, the same way it must be put on trial where it happens.

(…) Moreover, if a Lithuanian or a Rus [ Ruthenian ] wants to sue a German for an old thing, he must apply to the person to whom the person is subordinate; the same must be done by a German in Lithuania or Rus’.

(…) That peace was made in the one thousand three hundred and thirty-eighth year of the birth of God, on All Saints’ Day, with the consent of the Master, the Marshal of the Land and many other nobles, as well as the City Council of Riga; they kissed the cross on the matter; With the consent of the King of Lithuania [ Gediminas ], his sons and all his nobles; they also performed their sacred rites in this matter [ Pagan rites ]; and with the consent of the Bishop of Polotsk [ Gregory ], the Duke of Polotsk [ Narimantas ] and the city, the Duke of Vitebsk [ Algirdas ] and the city of Vitebsk; they all, in approval of the said peace treaty, kissed the cross.»

— From the 1338 Peace and Trade Agreement, concluded in Vilnius, between the Grand Duke of Lithuania Gediminas and his sons and the Master of the Livonian Order Everhard von Monheim, establishing a peace zone, which clearly distinguishes the Lithuanians and the Rus’ people [ Ruthenians ], and Lithuania from Rus’ [ Ruthenia ].[122][123]

In 1260, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the land of Lithuania, and ethnic Lithuanians formed the majority (67.5%) of its 400,000 people.[124] With the acquisition of new Ruthenian territories, in 1340 this portion decreased to 30%.[125] By the time of the largest expansion towards Rus’ lands, which came at the end of the 13th and during the 14th century, the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was 800 to 930 thousand km2, just 10% to 14% of which was ethnically Lithuanian.[124][126]

On 6 May 1434, Grand Duke Sigismund Kęstutaitis released his privilege which tied the Orthodox and Catholic Lithuanian nobles rights in order to attract the Slavic nobles of the eastern regions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania who supported the former Grand Duke Švitrigaila.[127]

An estimate of the population in the territory of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania together gives a population at 7.5 million for 1493, breaking them down by ethnicity at 3.75 million Ruthenians (ethnic Ukrainians, Belarusians), 3.25 million Poles and 0.5 million Lithuanians.[128] With the Union of Lublin, 1569, Lithuanian Grand Duchy lost large part of lands to the Polish Crown.

According to an analysis of the tax registers in 1572, Lithuania proper had 850,000 residents of which 680,000 were Lithuanians.[129]

In the mid and late 17th century, due to Russian and Swedish invasions, there was much devastation and population loss on throughout the Grand Duchy of Lithuania,[130] including ethnic Lithuanian population in Vilnius surroundings. Besides devastation, the Ruthenian population declined proportionally after the territorial losses to Russian Empire. By 1770 there were about 4.84 million inhabitants in the territory of 320 thousand km2, the biggest part of whom were inhabitants of Ruthenia and about 1.39 million or 29% – of ethnic Lithuania.[124] During the following decades, the population decreased in a result of partitions.[124]

Legacy[edit]

Prussian tribes (of Baltic origin) were the subject of Polish expansion, which was largely unsuccessful, so Duke Konrad of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to settle near the Prussian area of settlement. The fighting between Prussians and the Teutonic Knights gave the more distant Lithuanian tribes time to unite. Because of strong enemies in the south and north, the newly formed Lithuanian state concentrated most of its military and diplomatic efforts on expansion eastward.

The rest of the former Ruthenian lands were conquered by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Some other lands in Ukraine were vassalized by Lithuania later. The subjugation of Eastern Slavs by two powers created substantial differences between them that persist to this day. While there were certainly substantial regional differences in Kievan Rus’, it was the Lithuanian annexation of much of southern and western Ruthenia that led to the permanent division between Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians. And even four Grand Dukes of Lithuania are appeared on the Millennium of Russia monument.

In the 19th century, the romantic references to the times of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were an inspiration and a substantial part of both the Lithuanian and Belarusian national revival movements and Romanticism in Poland.

Notwithstanding the above, Lithuania was a kingdom under Mindaugas, who was crowned by the authority of Pope Innocent IV in 1253. Vytenis, Gediminas and Vytautas the Great also assumed the title of King, although uncrowned by the Pope. A failed attempt was made in 1918 to revive the Kingdom under a German Prince, Wilhelm Karl, Duke of Urach, who would have reigned as Mindaugas II of Lithuania.

In the first half of the 20th century, the memory of the multiethnic history of the Grand Duchy was revived by the Krajowcy movement,[131][132] which included Ludwik Abramowicz (Liudvikas Abramovičius), Konstancja Skirmuntt, Mykolas Römeris (Michał Pius Römer), Józef Albin Herbaczewski (Juozapas Albinas Herbačiauskas), Józef Mackiewicz and Stanisław Mackiewicz.[133][134] This feeling was expressed in poetry by Czesław Miłosz.[134]

Pseudoscientific theory of litvinism was developed since the 1990s.[135]

According to the 10th article of the Law on the State Flag and Other Flags of the Republic of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuvos Respublikos valstybės vėliavos ir kitų vėliavų įstatymas), adopted by the Seimas, the historical Lithuanian state flag (with horseback knight on a red field, which initial design dates back to the reign of Grand Duke Vytautas the Great)[136] must be constantly raised over the most important governmental buildings (e.g. Seimas Palace, Government of Lithuania and its ministries, Lithuanian courts, municipal council buildings) and significant historical buildings (e.g. Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, Trakai Island Castle), also in Kernavė and in the site of the Senieji Trakai Castle.[137]

Gallery[edit]

-

Vilnius Old Town — the political and cultural center of the Grand Duchy, today a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

-

-

-

-

Mir Castle — a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Belarus.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

-

Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

-

Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

-

Lithuanian double-Denar of Grand Duke Sigismund III Vasa with his monogram and Lithuanian Vytis (Waykimas), minted in Vilnius, 1621.

-

Recreation of the Lithuanian soldiers

-

Žemaitukas, a historic horse breed from Lithuania, known from the 6–7th centuries, used as a warhorse by the Lithuanians

-

-

Lithuanian soldiers of the 16th century.

-

Priest, lexicographer Konstantinas Sirvydas, the cherisher of the Lithuanian language in the 17th century

-

Coat of arms of the Grand Chancellors of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

-

Coat of arms of the Grand Marshals of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

-

Saliamonas Mozerka Slavočinskis’ book named Giesmes tikieimuy katholickam pridiarancias, o per metu szwietes giedamas: Kuriup priliduoda Pfalmay Dowida. s. in the Lithuanian language, published in Vilnius, 1646.

-

See also[edit]

- Cities of Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- Crimea

- History of Belarus

- History of Lithuania

- History of Ukraine

- List of Belarusian rulers

- List of Lithuanian rulers

- List of Ukrainian rulers

- Belarus

- Lithuania

- Ukraine

References[edit]

- ^ «History of the national coat of arms». Seimas. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Herby Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej i Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego. Orły, Pogonie, województwa, książęta, kardynałowie, prymasi, hetmani, kanclerze, marszałkowie (in Polish). Jagiellonian Library. 1875–1900. pp. 6, 30, 32, 58, 84, 130, 160, 264, 282, 300. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Vaitekūnas, Stasys. «Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės gyventojai». Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Tumelis, Juozas. «Abiejų Tautų tarpusavio įžadas». Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b Baranauskas, Tomas (2000). «Lietuvos valstybės ištakos» [The Lithuanian State] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Sužiedėlis, Saulius (2011). Historical dictionary of Lithuania (2nd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8108-4914-3.

- ^ Rowell S.C. Lithuania Ascending: A pagan empire within east-central Europe, 1295–1345. Cambridge, 1994. p. 289-290

- ^ Ch. Allmand, The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge, 1998, p. 731.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- ^ R. Bideleux. A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge, 1998. p. 122

- ^ Rowell, Lithuania Ascending, p. 289.

- ^ Z. Kiaupa. «Algirdas ir LDK rytų politika.» Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (Lietuvos istorijos vadovėlis). CD. (2003). Elektroninės leidybos namai: Vilnius.

- ^ Kowalska-Pietrzak, Anna (2015). «History of Poland During the Middle Ages» (PDF). Core.

- ^ N. Davies. Europe: A History. Oxford, 1996, p. 392.

- ^ J. Kiaupienė. Gediminaičiai ir Jogailaičiai prie Vytauto palikimo. Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (Lietuvos istorijos vadovėlis). CD. (2003) Elektroninės leidybos namai: Vilnius.

- ^ J. Kiaupienë, «Valdžios krizës pabaiga ir Kazimieras Jogailaitis.» Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (Lietuvos istorijos vadovėlis). CD. (2003). Elektroninės leidybos namai: Vilnius.

- ^ D. Stone. The Polish-Lithuanian state: 1386–1795. University of Washington Press, 2001, p. 63.

- ^ Zigmas Zinkevičius. Kelios mintys, kurios kyla skaitant Alfredo Bumblausko Senosios Lietuvos istoriją 1009-1795m. Voruta, 2005.

- ^ «Indo-European etymology : Query result». starling.rinet.ru.

- ^ Zinkevičius, Zigmas (30 November 1999). «Lietuvos vardo kilmė». Voruta (in Lithuanian). 3 (669). ISSN 1392-0677. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022.

- ^ Dubonis, Artūras (1998). Lietuvos didžiojo kunigaikščio leičiai: iš Lietuvos ankstyvųjų valstybinių struktūrų praeities (Leičiai of Grand Duke of Lithuania: from the past of Lithuanian stative structures (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos instituto leidykla.

- ^ Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Central European University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-963-9116-42-9.

- ^ «Archivum Lithuanicum» (PDF). Institute of the Lithuanian Language. Vilnius. 15: 81. 2013.

- ^ Kolodziejczyk, Dariusz (22 June 2011). The Crimean Khanate and Poland-Lithuania: International Diplomacy on the European Periphery (15th-18th Century). A Study of Peace Treaties Followed by Annotated Documents. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004191907 – via Google Books.

- ^ Depending on translation of the source, here and below original Rus’ name can be translated as Russia or Ruthenia.

- ^ Gedimino laiškai [Letters of Gediminas] (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Vilnius University, Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore. p. 2. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Rosenwein, Barbara H. (3 May 2018). Reading the Middle Ages, Volume II: From c.900 to c.1500, Third Edition. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442636804 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mickūnaitė, Giedrė (10 September 2006). Making a Great Ruler: Grand Duke Vytautas of Lithuania. Central European University Press. ISBN 9786155211072 – via Google Books.

- ^ Parker, William Henry (11 November 1969). «An Historical Geography of Russia». Aldine Publishing Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Kunitz, Joshua (11 November 1947). «Russia, the Giant that Came Last». Dodd, Mead – via Google Books.

- ^ Between Two Worlds: A Comparative Study of the Representations of Pagan Lithuania in the Chronicles of the Teutonic Order and Rus’

- ^ Lietuvos valdovo žodis pasauliui: atveriame mūsų žemę ir valdas kiekvienam geros valios žmogui

- ^ Loewe, Karl F. von (1976). Studien Zur Geschichte Osteuropas. Brill Archive. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-04-04520-0.

- ^ Kuolys, Darius (2005). «Lietuvos Respublika : idėjos ištakos». Senoji Lietuvos literatūra: 157–198. ISSN 1822-3656.

- ^ «Lithuania». Encarta. 1997. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Lituanica. Boston, 1970–1978, Vol.5 p.395

- ^ «Lithuania – History». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Lithuania Ascending p.50

- ^ A. Bumblauskas, Senosios Lietuvos istorija, 1009–1795 [The early history of Lithuania], Vilnius, 2005, p. 33.

- ^ Iršėnas, Marius; Račiūnaitė, Tojana (2015). The Lithuanian Millennium: History, Art and Culture (PDF). Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of Arts Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-609-447-097-4. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ By contemporary accounts, the Lithuanians called their early rulers kunigas (kunigai in plural). The word was borrowed from German – kuning, konig. Later on kunigas was replaced by the word kunigaikštis, used to describe to medieval Lithuanian rulers in modern Lithuanian, while kunigas today means priest.

- ^ Z.Kiaupa, J. Kiaupienė, A. Kunevičius. The History of Lithuania Before 1795. Vilnius, 2000. p. 43-127

- ^ a b c V. Spečiūnas. Lietuvos valdovai (XIII-XVIII a.): Enciklopedinis žinynas. Vilnius, 2004. p. 15-78.

- ^ «The Battle of Saule». VisitLithuania.net. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Batūra, Romas. Places of Fighting for Lithuania’s Freedom (PDF). General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Baranauskas, Tomas. «Medieval Lithuania – Chronology 1183–1283». viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Senosios Lietuvos istorija p. 44-45

- ^ «The Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 13–18th century». valstybingumas.lt. Seimas. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Kiaupa, Zigmantas; Jūratė Kiaupienė; Albinas Kunevičius (2000) [1995]. «Establishment of the State». The History of Lithuania Before 1795 (English ed.). Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History. pp. 45–72. ISBN 9986-810-13-2.

- ^ «Balt | people». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Lithuania Ascending p. 55

- ^ New Cambridge p. 706

- ^ a b Gudavičius, Edvardas; Matulevičius, Algirdas; Varakauskas, Rokas. «Vytenis». Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Rowell, Stephen Christopher (1994). Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire Within East-Central Europe, 1295–1345. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-107-65876-9. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ «Gediminas | grand duke of Lithuania». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (1948). A Study Of History (Volume II) (Fourth impression ed.). Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 172. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ «Vilnius | national capital, Lithuania». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ «Trakai—The Old Capital of Lithuania». VisitWorldHeritage.com. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ «Kęstutis | duke of Lithuania». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ «Algirdas | grand duke of Lithuania». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Hinson, E. Glenn (1995), The Church Triumphant: A History of Christianity Up to 1300, Mercer University Press, p. 438, ISBN 978-0-86554-436-9

- ^ Cherkas, Borys (30 December 2011). Битва на Синіх Водах. Як Україна звільнилася від Золотої Орди [Battle at Blue Waters. How Ukraine freed itself from the Golden Horde] (in Ukrainian). istpravda.com.ua. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ «Battle of the Vorskla River». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Kloczowski, Jerzy (2000), A History of Polish Christianity, Cambridge University Press, p. 55, ISBN 978-0-521-36429-4

- ^ «Vytautas the Great | Lithuanian leader». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jasas, Rimantas; Matulevičius, Algirdas. «Radvilos». Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jurginis, Juozas. «Goštautai». Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Matulevičius, Algirdas. «Vedrošos mūšis». Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Zikaras, Karolis (2017). Battle of Orsha 1514 (PDF). Vilnius: Ministry of National Defence of Lithuania. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-609-412-068-8. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Makuch, Andrij. «Ukraine: History: Lithuanian and Polish rule». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

Within the [Lithuanian] grand duchy the Ruthenian (Ukrainian and Belarusian) lands initially retained considerable autonomy. The pagan Lithuanians themselves were increasingly converting to Orthodoxy and assimilating into the Ruthenian culture. The grand duchy’s administrative practices and legal system drew heavily on Slavic customs, and an official Ruthenian state language (also known as Rusyn) developed over time from the language used in Rus. Direct Polish rule in Ukraine in the 1340s and for two centuries thereafter was limited to Galicia. There, changes in such areas as administration, law, and land tenure proceeded more rapidly than in Ukrainian territories under Lithuania. However, Lithuania itself was soon drawn into the orbit of Poland following the dynastic linkage of the two states in 1385/86 and the baptism of the Lithuanians into the Latin (Roman Catholic) church.

- ^ «Union of Lublin: Poland-Lithuania [1569]». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

Formally, Poland and Lithuania were to be distinct, equal components of the federation,[…] But Poland, which retained possession of the Lithuanian lands it had seized, had greater representation in the Diet and became the dominant partner.

- ^ Stranga, Aivars. «Lithuania: History: Union with Poland». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

While Poland and Lithuania would thereafter elect a joint sovereign and have a common parliament, the basic dual state structure was retained. Each continued to be administered separately and had its own law codes and armed forces. The joint commonwealth, however, provided an impetus for cultural Polonization of the Lithuanian nobility. By the end of the 17th century, it had virtually become indistinguishable from its Polish counterpart.

- ^ Eidintas, Alfonsas; Bumblauskas, Alfredas; Kulakauskas, Antanas; Tamošaitis, Mindaugas; Kondratas, Skirma; Kondratas, Ramūnas (2013). The history of Lithuania (PDF) (2nd ed.). Vilnius: Eugrimas. p. 101. ISBN 978-609-437-163-9. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b Marek Sobczyński. «Procesy integracyjne i dezintegracyjne na ziemiach litewskich w toku dziejów» [The process of integration and disintegration in the territories of Lithuania in the course of events] (PDF) (in Polish). Zakład Geografii Politycznej Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ «Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės administracinis teritorinis suskirstymas». vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ «Vilniaus barokas». vilniausbarokas.weebly.com (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ Vardys, Vytas Stanley. «Christianity in Lithuania». Lituanus.org. Lituanus. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Halych metropoly. Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ^ Gudavičius, Edvardas; Jučas, Mečislovas; Matulevičius, Algirdas. «Jogaila». Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ von Pastor, Ludwig (1899). The History of the Popes, from the Close of the Middle Ages. Vol. 6. p. 146. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

…he wrote to the Grand Duke of Lithuania, admonishing him to do everything in his power to persuade his consort to ‘abjure the Russian religion, and accept the Christian Faith.’

- ^ «1563 06 07 «Vilniaus privilegija» sulygino Lietuvos DK stačiatikių ir katalikų teises». DELFI (in Lithuanian). Lithuanian Institute of History. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Wisner, Henryk. «The Reformation and National Culture: Lithuania» (PDF). rcin.org.pl. Digital Repository of the Scientific Institutes (Poland). Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Slavenas, Maria Gražina. «The Reformation in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania». Lituanus.org. State University of New York. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Vilniaus Universitetas. History of Vilnius University. Retrieved on 2007.04.16

- ^ Górak-Sosnowska, Katarzyna. (2011). Muslims in Poland and Eastern Europe : widening the European discourse on Islam. University of Warsaw. Faculty of Oriental Studies. pp. 207–208. ISBN 9788390322957. OCLC 804006764.

- ^ Shirin Akiner (2009). Religious Language of a Belarusian Tatar Kitab: A Cultural Monument of Islam in Europe : with a Latin-script Transliteration of the British Library Tatar Belarusian Kitab (OR 13020) on CD-ROM. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-3-447-03027-4.

- ^ Hussain, Tharik (1 January 2016). «The amazing survival of the Baltic Muslims». BBC News. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ a b Daniel. Z Stone, A History of East Central Europe, p.4

- ^ a b c O’Connor, Kevin (2006), Culture and Customs of the Baltic States, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 115, ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1, retrieved 12 August 2016

- ^ a b c d Burant, S. R.; Zubek, V. (1993). «Eastern Europe’s Old Memories and New Realities: Resurrecting the Polish-lithuanian Union». East European Politics & Societies. 7 (2): 370–393. doi:10.1177/0888325493007002007. ISSN 0888-3254. S2CID 146783347.

- ^ a b Zinkevičius, Zigmas (1995). «Lietuvos Didžiosios kunigaikštystės kanceliarinės slavų kalbos termino nusakymo problema» (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Daniel. Z Stone, A History of East Central Europe, p.46

- ^ a b c d Wiemer, Björn (2003). «Dialect and language contacts on the territory of the Grand Duchy from the 15th century until 1939». In Kurt Braunmüller; Gisella Ferraresi (eds.). Aspects of Multilingualism in European Language History. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 109–114. ISBN 90-272-1922-2. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Dubonis, Artūras. «Lietuvių kalba: poreikis ir vartojimo mastai (XV a. antra pusė – XVI a. pirma pusė)». viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Stone, Daniel. The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386–1795. Seattle: University of Washington, 2001. p. 4.

- ^ Kamuntavičius, Rustis. Development of Lithuanian State and Society. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, 2002. p.21.

- ^ Eberhardt, Piotr (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe. M.E. Sharpe. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7656-1833-7. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Pancerovas, Dovydas. «Ar perrašinėjamos istorijos pasakų įkvėpta Baltarusija gali kėsintis į Rytų Lietuvą?». 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Statkuvienė, Regina. «Jogailaičiai. Kodėl ne Gediminaičiai?». 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Plikūnė, Dalia. «Kodėl Jogaila buvo geras, o Vytautas Didysis – genialus». DELFI (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Baronas, Darius (2013). Žemaičių krikštas: tyrimai ir refleksija (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lithuanian Catholic Academy of Science. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-9986-592-71-6. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Daniel. Z Stone, A History of East Central Europe, p.52

- ^ Lietuvių kalba ir literatūros istorija Archived 26 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stryjkowski, Maciej (1582). Kronika Polska, Litewska, Zmódzka i wszystkiéj Rusi. Warszawa Nak. G.L. Glüsksverga. p. 207. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Dubonis, Artūras (2002). «Lietuvių kalba: poreikis ir vartojimo mastai (XV a. antra pusė – XVI a. antra pusė)» [Lithuanian language: the need for and extent of use (second half XV c. – second half XVI c.)] (in Lithuanian). viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ […] не обчымъ яким языкомъ, але своимъ властнымъ права списаные маемъ …; Dubonis, A. Lietuvių kalba

- ^ Statut wielkiego ksiestwa litewskiego. (Statut des Großfürstenthums Lithauen.) (in Polish). 1786. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Narbutas, Sigitas. «Augustinas Rotundas». Vle.lt. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Trimonienė, Rita Regina. «Petro Tarvainio «Linksmas pasveikinimas» ir Šiaulių Šv. Petro ir Pauliaus bažnyčia». Lituanistika.lt (in Lithuanian and English). Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Menelis, E.; Samavičius, R. «Vilniaus miesto istorijos chronologija» (PDF). Vilnijosvartai.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ «Kauno rotušė». Autc.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Butėnas, Domas (1997). Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valstybinių ir visuomeninių institucijų istorijos bruožai XIII–XVIII a. Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos instituto leidykla. pp. 145–146.

- ^ Vytautas the Great; Valkūnas, Leonas (translation from Latin). Vytauto laiškai [ Letters of Vytautas the Great ] (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius University, Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore. p. 6. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ «Lietuvos etnografiniai regionai – ar pažįstate juos visus?». DELFI (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ «Aukštaitija». Ekgt.lt (in Lithuanian). Etninės kultūros globos taryba (Council for the Protection of Ethnic Culture). Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Drungila 2019, p. 131.

- ^ Pociūtė-Abukevičienė, Dainora. «Martynas Mažvydas». Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Tumelis, Juozas. «Abraomas Kulvietis». Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ «Konstantinas Sirvydas». Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Sirvydas, Konstantinas (1713). Dictionarium trium lingvarum in usum studiosae iuventutis. Vilnius: Academicis Societatis Jesu. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Sabaliauskas, Algirdas. «Universitas lingvarum Litvaniae». Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Rowell, Stephen Christopher (2003). Chartularium Lithuaniae res gestas magni ducis Gedeminne illustrans (PDF) (in German and Lithuanian). Vilnius: Vaga [lt]. pp. 380–385. ISBN 5-415-01700-3. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ «Chartularium Lithuaniae res gestas magni ducis Gedeminne illustrans / tekstus, vertimus bei komentarus parengė S.C. Rowell. – 2003». epaveldas.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Letukienė, Nijolė; Gineika, Petras (2003). «Istorija. Politologija: kurso santrauka istorijos egzaminui» (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Alma littera: 182. . Statistical numbers, usually accepted in historiography (the sources, their treatment, the method of measuring is not discussed in the source), are given, according to which in 1260 there were about 0.27 million Lithuanians out of a total population of 0.4 million (or 67.5%). The size of the territory of the Grand Duchy was about 200 thousand km2. The following data on population is given in the sequence – year, total population in millions, territory, Lithuanian (inhabitants of ethnic Lithuania) part of population in millions: 1340 – 0.7, 350 thousand km2, 0.37; 1375 – 1.4, 700 thousand km2, 0.42; 1430 – 2.5, 930 thousand km2, 0.59 or 24%; 1490 – 3.8, 850 thousand km2, 0.55 or 14% or 1/7; 1522 – 2.365, 485 thousand km2, 0.7 or 30%; 1568 – 2.8, 570 thousand km2, 0.825 million or 30%; 1572, 1.71, 320 thousand km2, 0.85 million or 50%; 1770 – 4.84, 320 thousand km2, 1.39 or 29%; 1791 – 2.5, 250 km2, 1.4 or 56%; 1793 – 1.8, 132 km2, 1.35 or 75%

- ^ Letukienė, N., Istorija, Politologija: Kurso santrauka istorijos egzaminui, 2003, p. 182; there were about 0.37 million Lithuanians of 0.7 million of a whole population by 1340 in the territory of 350 thousand km2 and 0.42 million of 1.4 million by 1375 in the territory of 700 thousand km2. Different numbers can also be found, for example: Kevin O’Connor, The History of the Baltic States, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-313-32355-0, Google Print, p.17. Here the author estimates that there were 9 million inhabitants in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and 1 million of them were ethnic Lithuanians by 1387.

- ^ Wiemer, Björn (2003). «Dialect and language contacts on the territory of the Grand Duchy from the 15th century until 1939». In Kurt Braunmüller; Gisella Ferraresi (eds.). Aspects of Multilingualism in European Language History. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 109, 125. ISBN 90-272-1922-2. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ^ «Žygimanto Kęstutaičio privilegija». Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Pogonowski, Iwo (1989), Poland: A Historical Atlas, Dorset, p. 92, ISBN 978-0-88029-394-5- Based on 1493 population map

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ «Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės gyventojai». Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian).

- ^ Kotilaine, J. T. (2005), Russia’s Foreign Trade and Economic Expansion in the Seventeenth Century: Windows on the World, Brill, p. 45, ISBN 90-04-13896-X, retrieved 12 August 2016