| Fehérlófia | |

|---|---|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Fehérlófia |

| Also known as | The Son of the White Horse; The Son of the White Mare |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 301 (Three Stolen Princesses) |

| Region | Hungary |

| Published in | Eredeti népmesék by László Arany (1862) |

| Related | Jean de l’Ours |

Fehérlófia (lit. The Son of the White Horse or The Son of the White Mare) is a Hungarian folk tale published by László Arany (hu) in Eredeti Népmesék (1862).[1] Its main character is a youth named Fehérlófia, a «Hungarian folk hero».[2]

The tale is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as tale type ATU 301, «The Three Stolen Princesses». However, the Hungarian National Catalogue of Folktales classifies the tale as MNK 301B.

Summary[edit]

It was, it was not, a white mare that nurses its own human child for fourteen years, until he is strong enough to uproot a tree. The mare dies and the boy departs to see the world. He wrestles with three other equally strong individuals: Fanyüvő, Kőmorzsoló and Vasgyúró. The three strike a friendship and move to a hut in the forest. They set an arrangement: one should stay in the hut and cook the food while the others hunt.

One day, a little man or dwarf named Hétszűnyű Kapanyányimonyók. He invades the hut and beats Fehérlófia’s companions to steal the food (a cauldron of porridge). Fehérlófia meets the dwarf and traps his beard in a tree trunk. The hero leads his friends to the dwarf’s location but he seems to have escaped to somewhere. Fehérlófia and the other heroes follow after and find a pit or a hole that leads deep underground.

After his companion feel too frightened to descend, Fehérlófia himself climbs down a rope (a basket) to the underground. Down there, he finds the dwarf, who points him to three castles in this vast underworld: one of copper, the second of silver and the third of gold. Inside every castle, there is a lovely princess, a captive of a serpentine or draconic enemy. Féherlofia rescues the princess of the copper castle by killing her three-headed dragon captor and goes to rescue her sistes[check spelling], the princess in the silver castle and the maiden of the golden castle.

He kills the six-headed dragon in the silver palace and the twelve-headed dragon of the golden palace. Then, all four return to the basket in order for the princesses to return to the upper world. Féherlófia lets the princess go first, since the four of them would impair the ascent of the basket. Some time later, the basket does not return to retrieve Fehérlófia, so he wanders about in the underworld and sees a nest of griffins chicks. He uses a bush to create a protection from the rain and the griffin bird arrives to thank him. The human hero says he could use some help to return to the upper world. The griffin is happy to oblige, but he needs to be fed on the way up.

Near the end of the ascent, Fehérlófia discovers the food supplies are gone, so, out of desperation, slices his own hand and leg to feed the bird. When they land, the griffin is astonished at the human’s sacrifice, so it gives him a vial of magical liquid to restore his strength. A restored Fehérlófia, then, searches for his traitorous companions to teach them a lesson. The trio is shocked to see his fallen companion back from the underworld and die of fright. Fehérlófia takes the princesses to their father and marries the youngest.

Variants[edit]

Europe[edit]

In a tale collected in the Vend Romani dialect, the youth is the son of a «white horse», but the narration says the boy’s father lifts the giant tree with a finger. Regardless, the boy is nursed by his mother for 21 years and finally uproots the tree. He travels the world and meets four other companions: Cliff-breaker, Hill-roller, Pine-twister and Iron-kneader. When he descends to the underworld, he rescues four princesses in the copper, silver, gold and diamond castles. Three of his companions marry three of the princesses, and the story concludes with the hero revealing Iron-kneader’s betrayal and marrying the diamond princess.[3]

A Romani-Bukovina variant, titled Mare’s Son, shows many identical elements with the Hungarian tale: the hero’s supernatural birth (by a mare); the mare nursing the boy; the tree uproot test; the three companions (Tree-splitter, Rock-splitter and Tree-bender); the small-sized man who steals the food; the descent to the underworld; the rescue of the eagle nest and the escape on the eagle’s back. However, in the Underworld, Mare’s Son puts the escaped dwarf in the basket and helps an elderly couple against an evil fairy that stole their eyes.[4] Its collector and publisher, scholar Francis Hindes Groome, noted that the tale was «clearly defective», lacking the usual elements, despite the parallels with several other stories.[5]

Hungary[edit]

Shepherd Paul watches as the princesses are roped to the upper world. Illustration by Henry Justice Ford for The Crimson Fairy Book (1903).

In another Hungarian tale, collected by János Erdélyi with the title Juhász Palkó[6] or Shepherd Paul, a shepherd finds a two-year-old boy in a meadow and names him Paul. He gives the boy to a ewe to suckle, and the boy develops great strength to uproot a tree after fourteen years. Paul goes to travel the world and meet three equally strong companions: Tree-Comber, Stone-Crusher and Iron-Kneader. They strike a friendship and set an arrangement: one will stay at home while the others go hunt some game. Paul’s three companions stay home and are attacked by a dwarf that steals their food. Paul defeats the dwarf and ties his giant beard to a giant tree. Paul scolds his companions and wants to show them the defeated foe, but he has vanished. They soon follow him to an opening that leads underground. Paul descends, enters three castles, kills three many-headed dragons, liberates three princesses and transforms the castles into golden apples with a magic wand. The last dragon he kills was the dwarf in the surface, under a different form. Paul is betrayed by his companions, protects a nest of griffins with his cloak and their father takes him to the surface after a three-day journey. After he rests a while, the hero goes after his traitorous companions, kills them and marries the youngest princess.[7]

Russia[edit]

In a Russian tale collected by Russian folklorist Ivan Khudyakov [ru] with the name «Иванъ — Кобьлинъ сынъ»[8] and translated as Ivan the Mare’s Son, from Riazan district, an old peasant couple buys a small mare from twelve brothers. Later, the old man buys a fine colt from a gentleman and forgets about the little mare. Feeling dejected, the mare flies away to the open steppes and gives birth to a human boy named Ivan, who grows by the hour. The human boy fixes some food and water for his equine mother and goes on a journey to rescue the tsar’s daughter, kidnapped by an evil twelve-headed serpent. He meets two companions on the road, Mount-Bogatyr and Oak-Bogatyr, and they set for the entrance to the serpent’s underground lair (this version lacks the episode of the little man and the hut). Ivan the Mare’s Son descends the well, kills the serpent and rescues the tsar’s daughter. His companions betray him and abandon him underground. Very soon (and suddenly), twelve doves appear and offer to take Ivan back to the surface (acting as the eagle of the other variants). After he arrives, he sees that his mother has died and ravens are pecking its body. He captures of the ravens as help in unmasking his traitorous companions.[9]

Mari people[edit]

Hungarian scholarship located a similar tale of the horse-born hero among the Mari people.[10] In a Hungarian translation of the tale, titled Vültak, a fehér kanca fia («Vültak, The Son of the White Mare»), hero Vültak is born of a white mare. He joins forces with two companions, Tölcsak («Son of the Moon») and Kecsamös («Son of the Sun»), and each of them marries a maiden. The three couples live together, until one day a strange personage tries to enter their house, but Vültak dismisses him. Some time later, the strange man beats the three heroes to a pulp and kidnaps their wives to his underground lair. Vültak’s mother, the white mare, heals the trio at the cost of her own life. Vültak descends to the underground with a rope, rescues the girls and defeats the villain (whose soul was hidden outside his body).[11]

Czech Republic[edit]

A similar tale, Neohrožený Mikeš [cz] was recorded in today’s Czech Republic by Božena Němcová. While some of the elements are missing, it follows the same general plot — Mikeš the main hero, a blacksmith’s son, was nursed by his mother for 18 years, and as such developed enormous strength. After forging himself a club out of 7 quintals of iron, he sets out; on the way he’s joined by two companions, named Kuba and Bobeš. They learn of three kidnapped princesses and decide to rescue them. Staying in a cave, a dwarf appears to each of them and attempts to kill them; however, Mikeš defeats him and takes his beard. He turns into an old woman, who tells them the princesses were kidnapped by a dragon and held in the underworld, and leads them to the entrance. Mikeš enters using a rope, finds two of the princesses, and using a magical candle defeats the creatures guarding them. The princesses are rescued, but the companions betray Mikeš by attempting to drop him to his death; he is warned and attaches his club instead. He then defeats the dragon and saves the third princess, who turned out to be the old woman. Together, they return to the princess’s castle, where they prevent the marriage of the other two sisters and the treacherous companions — who flee, never to be seen again.[12]

Literary variants[edit]

According to scholarship, Romanian author Ion Creanga used similar plot elements to write his literary tale Făt-frumos, fiul iepei («Făt-Frumos, Son of the Mare»),[13][14] or Prince Charming, the Mare’s Son.[15]

Analysis[edit]

Classification[edit]

According to scholar Ágnes Kovács, the tale belongs to type AaTh 301B, «The Strong Man and his Companions».[16][a] She also stated that Fehérlófia was «one of the most popular Hungarian tales»,[18] with more than 50 variants.[19] A recension by scholar Gabriella Kiss, in 1968, listed 64 variants across Hungarian sources.[20] Fieldwork conducted in 1999 by researcher Zoltán Vasvári amongst the Palóc population found 4 variants of the tale type.[21]

Scholarship also sees considerable antiquity in the tale.[22][23] For instance, Gabriella Kiss stated that the tale «Son of the White Horse» belonged to the «archaic material of Hungarian folk-tales».[24]

In regards to the journey on the back of a giant bird (an eagle or a griffin), folklorist scholarship recognizes its similarities with the tale of Etana helping an eagle, a tale type later classified as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 537, «The Eagle as helper: hero carried on the wings of a helpful eagle».[25]

Origins of the hero[edit]

In another tale of the same folktype, AaTh 301B («The Strong Man and his Companions»), named Jean de l’Ours, the hero is born from a human woman and a bear. The human woman is sometimes lost in the woods and the animal finds her, or she is taken by the animal to its den. In a second variation, the hero is fathered by a lion and he is called Löwensohn («The Lion’s Son»).

Professor Michael Meraklis cited that the episode of a lion or bear stealing a human woman and the hero born of this «living arrangement» must preserve «the original form of the tale», since it harks back to the ancient and primitive notion that humans and animals could freely interact in a mythical shared past.[26]

In the Hungarian tale, however, the father is unknown, and the non-human parentage is attributed to a female animal (the white mare). This fantastical birth could be explained by the fact that the character of Fehérlófia was «originally a totem animal ancestor».[27] This idea seems supported by the existence of other Hungarian tales with a horse- or mare-born hero (like Lófia Jankó and Lófi Jankó) — a trait also shared by Turkish[28] and Chuvash tales[b] — and the existence of peoples that claim descent from a mythical equine ancestor.[30] A similar conclusion has been reached in regards to the animal-born hero of Russian folktales: the hero «magically born from a totem» represents «the oldest character type».[31]

By comparing Romanian variants of type 301 to international tales, French philologist Jean Boutière, in his doctoral thesis, surmised that «much more often (especially in the West)», the hero is born of a union between a woman and a bear, but elsewhere, «notably in the East», the hero is the son of a mare, a she-donkey or even of a cow.[32]

Parallels[edit]

Professor Mihály Hoppál’s [de] study, titled Feherlófia, found «Eastern parallels» to the tale across the Eurasian steppes, in Mongols and Turkic peoples of Inner Asia and in Kyrgyz folklore (namely, the Er Töstük epic).[33] Also, according to him, the story of Fehérlófia does not have parallels in Europe, but belongs to a select group of tale types shared by Hungary and other Asian peoples.[34] In another article, he states that the type «can be traced all the way to the Far East (including the Yugur, Daur, Mongol and Turkic peoples of Central Asia)».[35]

In the same vein, professor Tünde Tancz says the type «belongs to the fairy tale area of West Asia», a region that encompasses «the repertoire of Finno-Ugric peoples and many Turkic peoples».[36] Similarly, researcher Izabella Horváth argues that the tale shows great parallels to tales from Osmali Turks, Uigurs, Kazaks, Yugurs and Kyrgyzes.[37]

Parallels have also been argued between Fehérlófia and other Inner Asian stories that follow the same narrative sequence and involve an animal-born hero, in particular an Asian tale from the collection of Vetala (also known as The Bewitched Corpse Cycle) about a cow-born hero.[38][39]

Adaptations[edit]

The tale was used as the plot of the 1981 Hungarian animated fantasy film Fehérlófia («Son of the White Mare»), by film director Marcell Jankovics.

See also[edit]

- Hungarian mythology

- Prâslea the Brave and the Golden Apples (Romanian fairy tale)

- The Story of Bensurdatu (Italian fairy tale)

- Dawn, Midnight and Twilight (Russian fairy tale)

- The Gnome (German fairy tale)

- The Norka (Russian fairy tale)

- Miloš Obilić, legendary Serbian hero

- The Son of a Horse (Chinese folktale)

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ It should be noted, however, that the third revision of the Aarne-Thompson classification system, made in 2004 by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther, subsumed both subtypes AaTh 301A and AaTh 301B into the new type ATU 301.[17]

- ^ Bashkir folklorist Nur T. Zaripov [ru] published a tale from the Bashkirs (another Turkic people) with the title «Бузансы-батыр» («Buzansy-Batyr»): an old couple have a gray mare named Buzbia that gives birth to a human boy after a harsh winter. The boy is raised by the human couple, given the name Buzansy-Batyr and meets companions in his youth. The tale then veers into tale type ATU 513A, «How Six Made Their Way Through the World».[29]

References[edit]

- ^ László Arany. Eredeti népmesék. Pest: Nyomatott Landerer és Heckenastnál. 1862. pp. 202-215.

- ^ Sándor, András. [Reviewed Work: Fehérlófia by László Kemenes Géfin]. In: World Literature Today 54, no. 1 (1980): 142-43. doi:10.2307/40134687.

- ^ VEKERDI, J., and L. VEKERDI. «THE VEND GYPSY DIALECT IN HUNGARY». In: Acta Linguistica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 34, no. 1/2 (1984): 65-86. Accessed March 2, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44310143.

- ^ Groome, Francis Hindes. Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. 1899. pp. 74-79. [1]

- ^ Groome, Francis Hindes. Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. 1899. pp. 79-80. [2]

- ^ Erdélyi János. Népdalok és mondák. A Kisfaludy-Társaság megbizásábul szerkeszti és kiadja, 3 köt. Pest: Beimel József, 1848. pp. 319–324.

- ^ The Folk-Tales of the Magyars: Collected by Kriza, Erdélyi, Pap, and Others. Editor: W. Henry Jones and Lajos Kropf. London: Published for the Folk-lore Society. 1889. pp. 244-249.

- ^ Khudi︠a︡kov, Ivan Aleksandrovich. «Великорусскія сказки» [Tales of Great Russia]. Vol. 2. Saint Petersburg: 1861. pp. 39-43.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. An Anthology of Russian Folktales. Routledge. 2009. pp. 27-30. ISBN 9780765623058.

- ^ Hóppál, Mihály. Fehérlófia. Európai Folklór Intézet, 2007. p. 122. ISBN 9789639683860

- ^ Árvay János; Enyedy György. Kígyót szült az öregasszony: Mari Népmesék. Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó, 1962. 15-24.

- ^ Němcová, Božena. [3]. Čertův švagr; Neohrožený Mikeš ; O Nesytovi ; Silný Ctibor. Prague: Jan Laichter, 1912. p. 22.

- ^ Creanga, Ion. Făt-frumos, fiul iepei.

- ^ Stein, Helga. «VII. Besprechungen. Birlea, Ovidiu, Povestile Ion Creangä (Creangas Geschichten). Studu de folclor (Volkskundliche Studien), Literaturverlag (Bukarest) 1967. 318S». In: Fabula 10, no. Jahresband (1969): 225, 227. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1969.10.1.221

- ^ Creangă, Ion. Folk Tales from Roumania. Translated by Mabel Nandris. Routledge and Kegan Paul. 1952. pp. 67ff. ISBN 9787230009669.

- ^ Kovács, Agnes. «Rhythmus und Metrum in den ungarischen Volksmärchen»». In: Fabula 9, no. 1-3 (1967): 172. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1967.9.1-3.169

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg. The types of International Folktales. A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Folklore Fellows Communicatins (FFC) n. 284. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia-Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2004. p. 177.

- ^ A similar assessment is shared by professor Éva Vígh: «Az egyik legnépszerűbb magyar népmesénk a Fehérlófia. Ez a népmesetípus Európa-szerte megtalálható, de a magyar népmesevilágban különösen népszerű». Vígh Éva. ÁLLATSZIMBÓLUMTÁR: A-Z. Budapest: Balassi Kiadó. [2018?] p. 206. ISBN 978-963-456-049-4.

- ^ Kovács Ágnes. «Fehérlófia». In: Ortutay Gyula főszerk. Magyar Néprajzi Lexikon. Volume 1. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1979. pp. 92–93.

- ^ Kiss, Gabriella. «Hungarian Redactions of the Tale Type 301». In: Acta Ethnographica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 17 (1968): 357-358.

- ^ VASVÁRI Zoltán. «Népmese a Palócföldön». In: Palócföld 1999/2, pp. 93-94.

- ^ Tancz Tünde. «Evolúciós pszichológiai közelítések a népmeséhez». In: Fordulópont 9/1, évf. 39. 2008. p. 30.

- ^ Gulyás Judit. «„nyelve, hogy úgy szóljunk, népmeseileg legmagyarabb”. Az Arany család és Arany László mesegyűjteményének szinoptikus kiadásáról» [«Its Language is, so to speak, the most Hungarian in the World of Folklore”. On the Synoptic Edition of the Tale Collection of the Arany Family and László Arany]. In: Helikon: IRODALOM- ÉS KULTÚRATUDOMÁNYI SZEMLE 2021/1: Genetikus kritika. LXVII évfolyam. p. 149.

- ^ Kiss, Gabriella. «Hungarian Redactions of the Tale Type 301». In: Acta Ethnographica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 17 (1968): 365.

- ^ Annus, Amar & Sarv, Mari. «The Ball Game Motif in the Gilgamesh Tradition and International Folklore». In: Mesopotamia in the Ancient World: Impact, Continuities, Parallels. Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium of the Melammu Project Held in Obergurgl, Austria, November 4–8, 2013. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag — Buch- und Medienhandel GmbH. 2015. pp. 289-290. ISBN 978-3-86835-128-6

- ^ Merakles, Michales G. Studien zum griechischen Märchen. Eingeleitet, übers, und bearb. von Walter Puchner. (Raabser Märchen-Reihe, Bd. 9. Wien: Österr. Museum für Volkskunde, 1992. p. 128. ISBN 3-900359-52-0

- ^ Szilárdi, Réka (2013). «Neopaganism in Hungary: Under the Spell of Roots». In: Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Acumen Publishing. p. 241

- ^ Buday, Kornélia. The earth has given birth to the sky: female spirituality in the Hungarian folk religion. Budapest : Akadémiai Kiadó; European Folklore Institute, 2004. p. 30.

- ^ Зарипов Н.Т. (сост.). Башкирское народное творчество [ru] [Bashkir Folk Art]. Том 3: Богатырские сказки [Tales of Bogatyrs]. Уфа, 1988. pp. 197-200, 422.

- ^ RÁSONYI, L. «L’ORIGINE DU NOM Székely (SICULE)». In: Acta Linguistica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 11, no. 1/2 (1961): 186-187. Accessed March 2, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44309192.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 127. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9

- ^ Boutière, Jean. La vie et l’oeuvre de Ion Creangă. Paris: Librairie Universitaire J. Gamber, 1930. p. 111.

- ^ Pócs, Éva. «The Hungarian táltos and the shamanism of pagan Hungarians. Questions and hypotheses». In: Acta Ethnographica Hungarica 63, 1 (2018): 178-179. accessed Mar 2, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1556/022.2018.63.1.9

- ^ Bartha Júlia. Hoppál Mihály (szerk.): Fehérlófia. In: HONISMERET: A Honismereti Szövetseg Folyoirata. XXXVI Évfolyam. 2008/3. p. 93.

- ^ Hoppál Mihály. «Kell-e nekünk magyar mitológia?». In: Magyar Napló XXVII: 8. 2015. p. 47.

- ^ Tancz Tünde. «Evolúciós pszichológiai közelítések a népmeséhez». In: Fordulópont 9/1, évf. 39. 2008. p. 30.

- ^ Horváth, Izabella. «A Comparative Study of the Shamanistic Motifs in Hungarian and Turkic Folk tales». In: Shamanism in Performing Arts. Eds. Tae-gon Kim and Mihâly Hoppâl. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1995. pp. 160-163.

- ^ Windhoffer Tímea. «A Fehérlófia Belső-Ázsiában». In: Birtalan Ágnes; Rákos Attila (szerk.). Bolor-un gerel. Kristályfény. The Crystal-Splendour of Wisdom. Essay Presented in Honour of Professor Kara György’s 70th Birthday. Vol. II. Budapest: ELTE Belső-ázsiai Tanszék‒MTA Altajisztikai Kutatócsoport. 2005. pp. 901–909. ISBN 963 463 767 1.

- ^ «A mongol eredetmondák, mítoszok». In: Birtalan Ágnes; Apatóczky Ákos Bertalan; Gáspár Csaba; Rákos Attila; Szilágyi Zsolt (editors). Miért jön a nyárra tél? Mongol eredetmondák és mítoszok [Mongolian proverbs and myths]. Budapest: Terebess Kiadó, 1998. pp. 5-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Horváth, Izabella (1994). “A fehérlófia mesetipus párhuzamai a Magyar és török népmesekben” [Parallel construction of Son-of White-Horse folk tale type in Hungarian and Turkic folk tales]. In: Történeti és Néprajzi Tanulmányok. Zoltán Ujváry ed. Debrecen. pp. 80–92.

- Kollarits, J., and I. Kollaritz. «Reviewed Work: Die ungarische Urreligion (Ungarisch). Magyar Szemle. Bd. 15 by S. Solymossy». In: Zeitschrift Für Ethnologie 66, no. 1/3 (1934): 277–79. Accessed March 2, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25839481.

External links[edit]

- Fehérlófia at Project Gutenberg

| Fehérlófia | |

|---|---|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Fehérlófia |

| Also known as | The Son of the White Horse; The Son of the White Mare |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 301 (Three Stolen Princesses) |

| Region | Hungary |

| Published in | Eredeti népmesék by László Arany (1862) |

| Related | Jean de l’Ours |

Fehérlófia (lit. The Son of the White Horse or The Son of the White Mare) is a Hungarian folk tale published by László Arany (hu) in Eredeti Népmesék (1862).[1] Its main character is a youth named Fehérlófia, a «Hungarian folk hero».[2]

The tale is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as tale type ATU 301, «The Three Stolen Princesses». However, the Hungarian National Catalogue of Folktales classifies the tale as MNK 301B.

Summary[edit]

It was, it was not, a white mare that nurses its own human child for fourteen years, until he is strong enough to uproot a tree. The mare dies and the boy departs to see the world. He wrestles with three other equally strong individuals: Fanyüvő, Kőmorzsoló and Vasgyúró. The three strike a friendship and move to a hut in the forest. They set an arrangement: one should stay in the hut and cook the food while the others hunt.

One day, a little man or dwarf named Hétszűnyű Kapanyányimonyók. He invades the hut and beats Fehérlófia’s companions to steal the food (a cauldron of porridge). Fehérlófia meets the dwarf and traps his beard in a tree trunk. The hero leads his friends to the dwarf’s location but he seems to have escaped to somewhere. Fehérlófia and the other heroes follow after and find a pit or a hole that leads deep underground.

After his companion feel too frightened to descend, Fehérlófia himself climbs down a rope (a basket) to the underground. Down there, he finds the dwarf, who points him to three castles in this vast underworld: one of copper, the second of silver and the third of gold. Inside every castle, there is a lovely princess, a captive of a serpentine or draconic enemy. Féherlofia rescues the princess of the copper castle by killing her three-headed dragon captor and goes to rescue her sistes[check spelling], the princess in the silver castle and the maiden of the golden castle.

He kills the six-headed dragon in the silver palace and the twelve-headed dragon of the golden palace. Then, all four return to the basket in order for the princesses to return to the upper world. Féherlófia lets the princess go first, since the four of them would impair the ascent of the basket. Some time later, the basket does not return to retrieve Fehérlófia, so he wanders about in the underworld and sees a nest of griffins chicks. He uses a bush to create a protection from the rain and the griffin bird arrives to thank him. The human hero says he could use some help to return to the upper world. The griffin is happy to oblige, but he needs to be fed on the way up.

Near the end of the ascent, Fehérlófia discovers the food supplies are gone, so, out of desperation, slices his own hand and leg to feed the bird. When they land, the griffin is astonished at the human’s sacrifice, so it gives him a vial of magical liquid to restore his strength. A restored Fehérlófia, then, searches for his traitorous companions to teach them a lesson. The trio is shocked to see his fallen companion back from the underworld and die of fright. Fehérlófia takes the princesses to their father and marries the youngest.

Variants[edit]

Europe[edit]

In a tale collected in the Vend Romani dialect, the youth is the son of a «white horse», but the narration says the boy’s father lifts the giant tree with a finger. Regardless, the boy is nursed by his mother for 21 years and finally uproots the tree. He travels the world and meets four other companions: Cliff-breaker, Hill-roller, Pine-twister and Iron-kneader. When he descends to the underworld, he rescues four princesses in the copper, silver, gold and diamond castles. Three of his companions marry three of the princesses, and the story concludes with the hero revealing Iron-kneader’s betrayal and marrying the diamond princess.[3]

A Romani-Bukovina variant, titled Mare’s Son, shows many identical elements with the Hungarian tale: the hero’s supernatural birth (by a mare); the mare nursing the boy; the tree uproot test; the three companions (Tree-splitter, Rock-splitter and Tree-bender); the small-sized man who steals the food; the descent to the underworld; the rescue of the eagle nest and the escape on the eagle’s back. However, in the Underworld, Mare’s Son puts the escaped dwarf in the basket and helps an elderly couple against an evil fairy that stole their eyes.[4] Its collector and publisher, scholar Francis Hindes Groome, noted that the tale was «clearly defective», lacking the usual elements, despite the parallels with several other stories.[5]

Hungary[edit]

Shepherd Paul watches as the princesses are roped to the upper world. Illustration by Henry Justice Ford for The Crimson Fairy Book (1903).

In another Hungarian tale, collected by János Erdélyi with the title Juhász Palkó[6] or Shepherd Paul, a shepherd finds a two-year-old boy in a meadow and names him Paul. He gives the boy to a ewe to suckle, and the boy develops great strength to uproot a tree after fourteen years. Paul goes to travel the world and meet three equally strong companions: Tree-Comber, Stone-Crusher and Iron-Kneader. They strike a friendship and set an arrangement: one will stay at home while the others go hunt some game. Paul’s three companions stay home and are attacked by a dwarf that steals their food. Paul defeats the dwarf and ties his giant beard to a giant tree. Paul scolds his companions and wants to show them the defeated foe, but he has vanished. They soon follow him to an opening that leads underground. Paul descends, enters three castles, kills three many-headed dragons, liberates three princesses and transforms the castles into golden apples with a magic wand. The last dragon he kills was the dwarf in the surface, under a different form. Paul is betrayed by his companions, protects a nest of griffins with his cloak and their father takes him to the surface after a three-day journey. After he rests a while, the hero goes after his traitorous companions, kills them and marries the youngest princess.[7]

Russia[edit]

In a Russian tale collected by Russian folklorist Ivan Khudyakov [ru] with the name «Иванъ — Кобьлинъ сынъ»[8] and translated as Ivan the Mare’s Son, from Riazan district, an old peasant couple buys a small mare from twelve brothers. Later, the old man buys a fine colt from a gentleman and forgets about the little mare. Feeling dejected, the mare flies away to the open steppes and gives birth to a human boy named Ivan, who grows by the hour. The human boy fixes some food and water for his equine mother and goes on a journey to rescue the tsar’s daughter, kidnapped by an evil twelve-headed serpent. He meets two companions on the road, Mount-Bogatyr and Oak-Bogatyr, and they set for the entrance to the serpent’s underground lair (this version lacks the episode of the little man and the hut). Ivan the Mare’s Son descends the well, kills the serpent and rescues the tsar’s daughter. His companions betray him and abandon him underground. Very soon (and suddenly), twelve doves appear and offer to take Ivan back to the surface (acting as the eagle of the other variants). After he arrives, he sees that his mother has died and ravens are pecking its body. He captures of the ravens as help in unmasking his traitorous companions.[9]

Mari people[edit]

Hungarian scholarship located a similar tale of the horse-born hero among the Mari people.[10] In a Hungarian translation of the tale, titled Vültak, a fehér kanca fia («Vültak, The Son of the White Mare»), hero Vültak is born of a white mare. He joins forces with two companions, Tölcsak («Son of the Moon») and Kecsamös («Son of the Sun»), and each of them marries a maiden. The three couples live together, until one day a strange personage tries to enter their house, but Vültak dismisses him. Some time later, the strange man beats the three heroes to a pulp and kidnaps their wives to his underground lair. Vültak’s mother, the white mare, heals the trio at the cost of her own life. Vültak descends to the underground with a rope, rescues the girls and defeats the villain (whose soul was hidden outside his body).[11]

Czech Republic[edit]

A similar tale, Neohrožený Mikeš [cz] was recorded in today’s Czech Republic by Božena Němcová. While some of the elements are missing, it follows the same general plot — Mikeš the main hero, a blacksmith’s son, was nursed by his mother for 18 years, and as such developed enormous strength. After forging himself a club out of 7 quintals of iron, he sets out; on the way he’s joined by two companions, named Kuba and Bobeš. They learn of three kidnapped princesses and decide to rescue them. Staying in a cave, a dwarf appears to each of them and attempts to kill them; however, Mikeš defeats him and takes his beard. He turns into an old woman, who tells them the princesses were kidnapped by a dragon and held in the underworld, and leads them to the entrance. Mikeš enters using a rope, finds two of the princesses, and using a magical candle defeats the creatures guarding them. The princesses are rescued, but the companions betray Mikeš by attempting to drop him to his death; he is warned and attaches his club instead. He then defeats the dragon and saves the third princess, who turned out to be the old woman. Together, they return to the princess’s castle, where they prevent the marriage of the other two sisters and the treacherous companions — who flee, never to be seen again.[12]

Literary variants[edit]

According to scholarship, Romanian author Ion Creanga used similar plot elements to write his literary tale Făt-frumos, fiul iepei («Făt-Frumos, Son of the Mare»),[13][14] or Prince Charming, the Mare’s Son.[15]

Analysis[edit]

Classification[edit]

According to scholar Ágnes Kovács, the tale belongs to type AaTh 301B, «The Strong Man and his Companions».[16][a] She also stated that Fehérlófia was «one of the most popular Hungarian tales»,[18] with more than 50 variants.[19] A recension by scholar Gabriella Kiss, in 1968, listed 64 variants across Hungarian sources.[20] Fieldwork conducted in 1999 by researcher Zoltán Vasvári amongst the Palóc population found 4 variants of the tale type.[21]

Scholarship also sees considerable antiquity in the tale.[22][23] For instance, Gabriella Kiss stated that the tale «Son of the White Horse» belonged to the «archaic material of Hungarian folk-tales».[24]

In regards to the journey on the back of a giant bird (an eagle or a griffin), folklorist scholarship recognizes its similarities with the tale of Etana helping an eagle, a tale type later classified as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 537, «The Eagle as helper: hero carried on the wings of a helpful eagle».[25]

Origins of the hero[edit]

In another tale of the same folktype, AaTh 301B («The Strong Man and his Companions»), named Jean de l’Ours, the hero is born from a human woman and a bear. The human woman is sometimes lost in the woods and the animal finds her, or she is taken by the animal to its den. In a second variation, the hero is fathered by a lion and he is called Löwensohn («The Lion’s Son»).

Professor Michael Meraklis cited that the episode of a lion or bear stealing a human woman and the hero born of this «living arrangement» must preserve «the original form of the tale», since it harks back to the ancient and primitive notion that humans and animals could freely interact in a mythical shared past.[26]

In the Hungarian tale, however, the father is unknown, and the non-human parentage is attributed to a female animal (the white mare). This fantastical birth could be explained by the fact that the character of Fehérlófia was «originally a totem animal ancestor».[27] This idea seems supported by the existence of other Hungarian tales with a horse- or mare-born hero (like Lófia Jankó and Lófi Jankó) — a trait also shared by Turkish[28] and Chuvash tales[b] — and the existence of peoples that claim descent from a mythical equine ancestor.[30] A similar conclusion has been reached in regards to the animal-born hero of Russian folktales: the hero «magically born from a totem» represents «the oldest character type».[31]

By comparing Romanian variants of type 301 to international tales, French philologist Jean Boutière, in his doctoral thesis, surmised that «much more often (especially in the West)», the hero is born of a union between a woman and a bear, but elsewhere, «notably in the East», the hero is the son of a mare, a she-donkey or even of a cow.[32]

Parallels[edit]

Professor Mihály Hoppál’s [de] study, titled Feherlófia, found «Eastern parallels» to the tale across the Eurasian steppes, in Mongols and Turkic peoples of Inner Asia and in Kyrgyz folklore (namely, the Er Töstük epic).[33] Also, according to him, the story of Fehérlófia does not have parallels in Europe, but belongs to a select group of tale types shared by Hungary and other Asian peoples.[34] In another article, he states that the type «can be traced all the way to the Far East (including the Yugur, Daur, Mongol and Turkic peoples of Central Asia)».[35]

In the same vein, professor Tünde Tancz says the type «belongs to the fairy tale area of West Asia», a region that encompasses «the repertoire of Finno-Ugric peoples and many Turkic peoples».[36] Similarly, researcher Izabella Horváth argues that the tale shows great parallels to tales from Osmali Turks, Uigurs, Kazaks, Yugurs and Kyrgyzes.[37]

Parallels have also been argued between Fehérlófia and other Inner Asian stories that follow the same narrative sequence and involve an animal-born hero, in particular an Asian tale from the collection of Vetala (also known as The Bewitched Corpse Cycle) about a cow-born hero.[38][39]

Adaptations[edit]

The tale was used as the plot of the 1981 Hungarian animated fantasy film Fehérlófia («Son of the White Mare»), by film director Marcell Jankovics.

See also[edit]

- Hungarian mythology

- Prâslea the Brave and the Golden Apples (Romanian fairy tale)

- The Story of Bensurdatu (Italian fairy tale)

- Dawn, Midnight and Twilight (Russian fairy tale)

- The Gnome (German fairy tale)

- The Norka (Russian fairy tale)

- Miloš Obilić, legendary Serbian hero

- The Son of a Horse (Chinese folktale)

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ It should be noted, however, that the third revision of the Aarne-Thompson classification system, made in 2004 by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther, subsumed both subtypes AaTh 301A and AaTh 301B into the new type ATU 301.[17]

- ^ Bashkir folklorist Nur T. Zaripov [ru] published a tale from the Bashkirs (another Turkic people) with the title «Бузансы-батыр» («Buzansy-Batyr»): an old couple have a gray mare named Buzbia that gives birth to a human boy after a harsh winter. The boy is raised by the human couple, given the name Buzansy-Batyr and meets companions in his youth. The tale then veers into tale type ATU 513A, «How Six Made Their Way Through the World».[29]

References[edit]

- ^ László Arany. Eredeti népmesék. Pest: Nyomatott Landerer és Heckenastnál. 1862. pp. 202-215.

- ^ Sándor, András. [Reviewed Work: Fehérlófia by László Kemenes Géfin]. In: World Literature Today 54, no. 1 (1980): 142-43. doi:10.2307/40134687.

- ^ VEKERDI, J., and L. VEKERDI. «THE VEND GYPSY DIALECT IN HUNGARY». In: Acta Linguistica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 34, no. 1/2 (1984): 65-86. Accessed March 2, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44310143.

- ^ Groome, Francis Hindes. Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. 1899. pp. 74-79. [1]

- ^ Groome, Francis Hindes. Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. 1899. pp. 79-80. [2]

- ^ Erdélyi János. Népdalok és mondák. A Kisfaludy-Társaság megbizásábul szerkeszti és kiadja, 3 köt. Pest: Beimel József, 1848. pp. 319–324.

- ^ The Folk-Tales of the Magyars: Collected by Kriza, Erdélyi, Pap, and Others. Editor: W. Henry Jones and Lajos Kropf. London: Published for the Folk-lore Society. 1889. pp. 244-249.

- ^ Khudi︠a︡kov, Ivan Aleksandrovich. «Великорусскія сказки» [Tales of Great Russia]. Vol. 2. Saint Petersburg: 1861. pp. 39-43.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. An Anthology of Russian Folktales. Routledge. 2009. pp. 27-30. ISBN 9780765623058.

- ^ Hóppál, Mihály. Fehérlófia. Európai Folklór Intézet, 2007. p. 122. ISBN 9789639683860

- ^ Árvay János; Enyedy György. Kígyót szült az öregasszony: Mari Népmesék. Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó, 1962. 15-24.

- ^ Němcová, Božena. [3]. Čertův švagr; Neohrožený Mikeš ; O Nesytovi ; Silný Ctibor. Prague: Jan Laichter, 1912. p. 22.

- ^ Creanga, Ion. Făt-frumos, fiul iepei.

- ^ Stein, Helga. «VII. Besprechungen. Birlea, Ovidiu, Povestile Ion Creangä (Creangas Geschichten). Studu de folclor (Volkskundliche Studien), Literaturverlag (Bukarest) 1967. 318S». In: Fabula 10, no. Jahresband (1969): 225, 227. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1969.10.1.221

- ^ Creangă, Ion. Folk Tales from Roumania. Translated by Mabel Nandris. Routledge and Kegan Paul. 1952. pp. 67ff. ISBN 9787230009669.

- ^ Kovács, Agnes. «Rhythmus und Metrum in den ungarischen Volksmärchen»». In: Fabula 9, no. 1-3 (1967): 172. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1967.9.1-3.169

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg. The types of International Folktales. A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Folklore Fellows Communicatins (FFC) n. 284. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia-Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2004. p. 177.

- ^ A similar assessment is shared by professor Éva Vígh: «Az egyik legnépszerűbb magyar népmesénk a Fehérlófia. Ez a népmesetípus Európa-szerte megtalálható, de a magyar népmesevilágban különösen népszerű». Vígh Éva. ÁLLATSZIMBÓLUMTÁR: A-Z. Budapest: Balassi Kiadó. [2018?] p. 206. ISBN 978-963-456-049-4.

- ^ Kovács Ágnes. «Fehérlófia». In: Ortutay Gyula főszerk. Magyar Néprajzi Lexikon. Volume 1. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1979. pp. 92–93.

- ^ Kiss, Gabriella. «Hungarian Redactions of the Tale Type 301». In: Acta Ethnographica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 17 (1968): 357-358.

- ^ VASVÁRI Zoltán. «Népmese a Palócföldön». In: Palócföld 1999/2, pp. 93-94.

- ^ Tancz Tünde. «Evolúciós pszichológiai közelítések a népmeséhez». In: Fordulópont 9/1, évf. 39. 2008. p. 30.

- ^ Gulyás Judit. «„nyelve, hogy úgy szóljunk, népmeseileg legmagyarabb”. Az Arany család és Arany László mesegyűjteményének szinoptikus kiadásáról» [«Its Language is, so to speak, the most Hungarian in the World of Folklore”. On the Synoptic Edition of the Tale Collection of the Arany Family and László Arany]. In: Helikon: IRODALOM- ÉS KULTÚRATUDOMÁNYI SZEMLE 2021/1: Genetikus kritika. LXVII évfolyam. p. 149.

- ^ Kiss, Gabriella. «Hungarian Redactions of the Tale Type 301». In: Acta Ethnographica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 17 (1968): 365.

- ^ Annus, Amar & Sarv, Mari. «The Ball Game Motif in the Gilgamesh Tradition and International Folklore». In: Mesopotamia in the Ancient World: Impact, Continuities, Parallels. Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium of the Melammu Project Held in Obergurgl, Austria, November 4–8, 2013. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag — Buch- und Medienhandel GmbH. 2015. pp. 289-290. ISBN 978-3-86835-128-6

- ^ Merakles, Michales G. Studien zum griechischen Märchen. Eingeleitet, übers, und bearb. von Walter Puchner. (Raabser Märchen-Reihe, Bd. 9. Wien: Österr. Museum für Volkskunde, 1992. p. 128. ISBN 3-900359-52-0

- ^ Szilárdi, Réka (2013). «Neopaganism in Hungary: Under the Spell of Roots». In: Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Acumen Publishing. p. 241

- ^ Buday, Kornélia. The earth has given birth to the sky: female spirituality in the Hungarian folk religion. Budapest : Akadémiai Kiadó; European Folklore Institute, 2004. p. 30.

- ^ Зарипов Н.Т. (сост.). Башкирское народное творчество [ru] [Bashkir Folk Art]. Том 3: Богатырские сказки [Tales of Bogatyrs]. Уфа, 1988. pp. 197-200, 422.

- ^ RÁSONYI, L. «L’ORIGINE DU NOM Székely (SICULE)». In: Acta Linguistica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 11, no. 1/2 (1961): 186-187. Accessed March 2, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44309192.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 127. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9

- ^ Boutière, Jean. La vie et l’oeuvre de Ion Creangă. Paris: Librairie Universitaire J. Gamber, 1930. p. 111.

- ^ Pócs, Éva. «The Hungarian táltos and the shamanism of pagan Hungarians. Questions and hypotheses». In: Acta Ethnographica Hungarica 63, 1 (2018): 178-179. accessed Mar 2, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1556/022.2018.63.1.9

- ^ Bartha Júlia. Hoppál Mihály (szerk.): Fehérlófia. In: HONISMERET: A Honismereti Szövetseg Folyoirata. XXXVI Évfolyam. 2008/3. p. 93.

- ^ Hoppál Mihály. «Kell-e nekünk magyar mitológia?». In: Magyar Napló XXVII: 8. 2015. p. 47.

- ^ Tancz Tünde. «Evolúciós pszichológiai közelítések a népmeséhez». In: Fordulópont 9/1, évf. 39. 2008. p. 30.

- ^ Horváth, Izabella. «A Comparative Study of the Shamanistic Motifs in Hungarian and Turkic Folk tales». In: Shamanism in Performing Arts. Eds. Tae-gon Kim and Mihâly Hoppâl. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1995. pp. 160-163.

- ^ Windhoffer Tímea. «A Fehérlófia Belső-Ázsiában». In: Birtalan Ágnes; Rákos Attila (szerk.). Bolor-un gerel. Kristályfény. The Crystal-Splendour of Wisdom. Essay Presented in Honour of Professor Kara György’s 70th Birthday. Vol. II. Budapest: ELTE Belső-ázsiai Tanszék‒MTA Altajisztikai Kutatócsoport. 2005. pp. 901–909. ISBN 963 463 767 1.

- ^ «A mongol eredetmondák, mítoszok». In: Birtalan Ágnes; Apatóczky Ákos Bertalan; Gáspár Csaba; Rákos Attila; Szilágyi Zsolt (editors). Miért jön a nyárra tél? Mongol eredetmondák és mítoszok [Mongolian proverbs and myths]. Budapest: Terebess Kiadó, 1998. pp. 5-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Horváth, Izabella (1994). “A fehérlófia mesetipus párhuzamai a Magyar és török népmesekben” [Parallel construction of Son-of White-Horse folk tale type in Hungarian and Turkic folk tales]. In: Történeti és Néprajzi Tanulmányok. Zoltán Ujváry ed. Debrecen. pp. 80–92.

- Kollarits, J., and I. Kollaritz. «Reviewed Work: Die ungarische Urreligion (Ungarisch). Magyar Szemle. Bd. 15 by S. Solymossy». In: Zeitschrift Für Ethnologie 66, no. 1/3 (1934): 277–79. Accessed March 2, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25839481.

External links[edit]

- Fehérlófia at Project Gutenberg

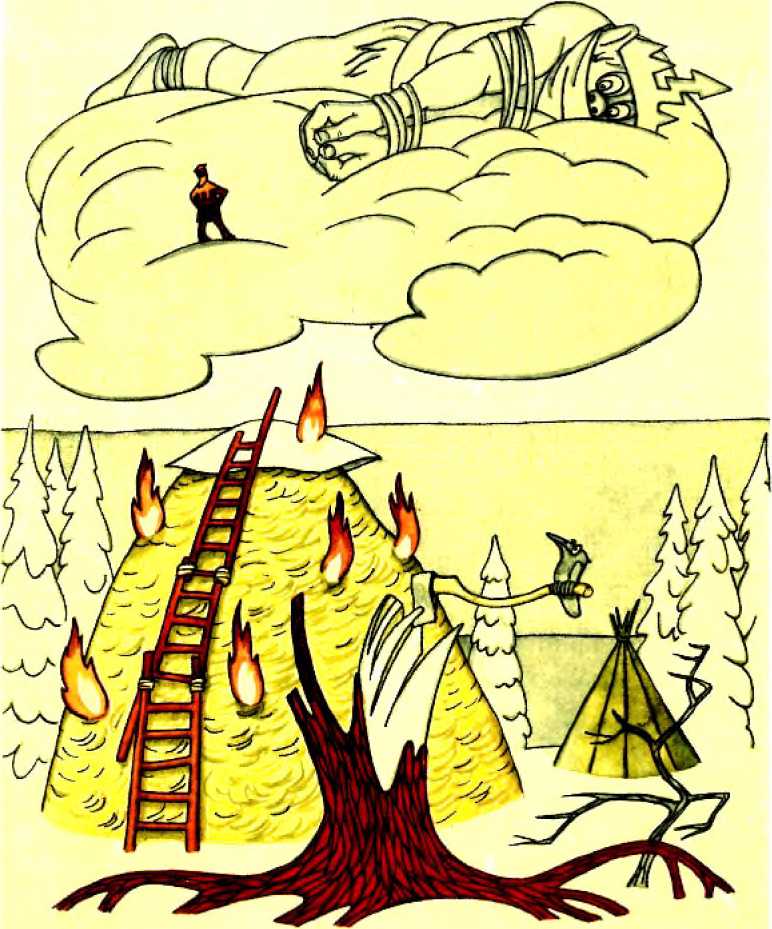

И, конечно, он не испугался. Спустился под землю, вылез из своей корзинки и решил осмотреться кругом.

Бродил он там под землей взад и вперед и вдруг приметил маленький домик. Вошел в него и кого же там увидел? Самого длиннобородого Бакараста. Тот сидел в хижине и смазывал жиром свою бороду и подбородок, а на очаге кипел котелок с кашей.

— Ну, старик, — сказал ему Сын белой лошади, — хорошо, что ты нашелся. Хотел ты съесть кашу с моего живота, а теперь я съем кашу с твоего живота.

Он схватил длиннобородого Бакараста, хлопнул его оземь, вылил кашу на его живот и так ее съел. Потом вывел Бакараста из дома, привязал к дереву и пошел дальше.

Вот он шел себе и шел, подошел к большому замку, окруженному медным полем и медным лесом.

Обошел замок кругом, потом вошел в него. В замке его встретила прекрасная девушка. Увидела она человека с земли и испугалась.

— Что тебе надо здесь, человек? Сюда ведь даже птица не залетает!

— Да я гнался тут за одним старичком, вот и забрел сюда, — ответил Сын белой лошади.

— Ну, тогда прощайся с жизнью. Вернется мой муж, трехглавый дракон, и убьет тебя. Спрячься скорей!

— Не стану я прятаться, — отвечал Сын белой лошади. — Я его осилю.

Только он это произнес, как появился дракон.

— Ну, собака, — сказал он Сыну белой лошади, — теперь ты помрешь! Пойдем биться с тобой на медный ток.

И они начали биться. Но Сын белой лошади тут же повалил дракона и отрубил все три его головы. Затем он вернулся к девушке и сказал ей:

— Освободил я тебя, красавица, подымемся со мной на землю.

— Милый мой освободитель, — ответила девушка, — у меня ведь здесь внизу еще две сестренки, тех тоже драконы похитили. Освободи их, и самую красивую из нас отец отдаст тебе в жены да впридачу отвалит еще половину своего добра.

— Ладно, — сказал Сын белой лошади. — Пойдем поищем их.

Они отправились на поиски.

Вот шли они, шли, и встретился им на пути серебряный замок, окруженный серебряным лесом и серебряным полем.

— Ты спрячься здесь, в лесу, — сказал Сын белой лошади девушке, — а я пойду за твоей сестрой.

Девушка спряталась в лесу, а Сын белой лошади вошел в замок. В замке его встретила девушка, она была еще красивее первой. Как увидела она его, испугалась и закричала:

— Человек с земли, как ты попал сюда, куда даже птица не залетает?

— Пришел освободить тебя.

— Ой, напрасно ты пришел. Вот вернется мой муж, шестиглавый дракон, и разорвет тебя на куски.

А дракон уж тут как тут. Как увидел он Сына белой лошади, так сразу же признал его.

— Эй, собака, — закричал он ему, — ты убил моего брата и за это должен умереть! Пойдем биться на серебряный ток.

Пошли. Бились они долго. Сын белой лошади победил. Он повалил дракона на землю и отрезал все его шесть голов. Потом он взял обеих девушек и пошел с ними дальше, чтоб освободить их самую младшую сестренку.

Вот они шли, шли и вдруг набрели на золотой замок, окруженный золотым лесом и золотым полем.

Здесь Сын белой лошади спрятал обеих девушек в лесу, а сам вошел в замок. Его встретила красавица. Она чуть не обмерла от удивления.

— Что тебе надо здесь, куда даже птица не залетает? — спросила она его.

— Я пришел тебя освободить, — ответил Сын белой лошади.

— Ой, напрасно ты трудился. Вот придет мой муж, двенадцатиглавый дракон, и раздерет он тебя, разорвет на клочки.

Едва она это успела сказать, как страшно затрещали ворота.

— Это мой муж запустил в них булавой, — сказала девушка. — А ведь он еще в семи милях отсюда! Но он мигом будет здесь. Милый юноша, спрячься поскорее!

Но если бы Сын белой лошади даже захотел, все равно бы ему не спрятаться, дракон уже был тут как тут.

Только он увидел Сына белой лошади, как сразу его признал:

— Ну, собака, хорошо, что ты пришел. Убил ты моих братьев, и если в тебе была бы даже тысяча душ, все они погибнут. Убью я тебя все равно, на клочки разорву. Но пойдем на золотой ток, там поборемся.

Долго они бились и никак не могли одолеть друг друга.

Наконец дракон так ударил Сына белой лошади, что тот ушел по колено в землю. Тогда Сын белой лошади вскочил и ударил дракона так, что тот погрузился в землю по пояс.

Вскочил дракон и снова ударил Сына белой лошади. Тот ушел по грудь в землю. Тогда Сын белой лошади разъярился, вскочил и так хватил дракона по плечу, что тот погрузился в землю, только головы торчали наружу.

Недолго думая, Сын белой лошади выхватил свою саблю и отрубил дракону все его двенадцать голов.

Потом он вернулся в замок и увел с собой всех трех сестер. Подошли они к той корзинке, в которой спустился в преисподнюю Сын белой лошади, но, как ни пытались, никак не могли усесться в ней вчетвером.

Тогда Сын белой лошади посадил девушек в корзину, а сам остался внизу и стал дожидаться, пока и за ним спустят корзину.

Ждал, ждал он три ночи, три дня. Бедняга, конечно, мог так хоть век прождать. Помощники его, вытянув девушек на землю, обрадовались и решили, что они сами доставят их домой. Зачем, дескать, спускать корзину для Сына белой лошади, пусть он лучше останется там, под землей.

Сын белой лошади ждал, ждал корзины, наконец терпение его кончилось. Потерял он надежду, что его вытащат из-под земли, и пошел прочь, понурый, унылый.

Едва успел он немного пройти, как вдруг разразился страшный ливень. Он укрылся своей шубой. А дождь все лил и лил. Сын белой лошади решил отыскать для себя хоть какой-нибудь кров.

Оглянувшись, он вдруг увидел гнездо грифа, а в нем трех погибавших под дождем птенцов. Он не только что не тронул их, но пожалел малышей, покрыл их своей шубой, а сам залез под куст.

Вдруг прилетела мать грифов.

— Кто же это вас укрыл? — спросила она сыновей.

— Мы не скажем тебе, а то ты его убьешь.

— Да что вы! Я его не трону. Наоборот, хочу его поблагодарить.

— Вон он лежит под кустом.

Мать грифов подошла к кустарнику и спросила Сына белой лошади:

— Как мне отблагодарить тебя за то, что ты спас моих сыновей?

— Не нужно мне ничего, — ответил Сын белой лошади.

— Нет, ты чего-нибудь пожелай. Не можешь ты уйти без моей благодарности.

— Ну, тогда отнеси меня на землю!

А мать грифов сказала:

— Эх, если бы кто-нибудь другой посмел меня об этом попросить, — знай, что не прожил бы он и часу! А ты пойди возьми три хлеба и три окорока. Привяжи хлеб с левой стороны, окорока с правой. Как поверну я голову направо, дай мне один хлеб, поверну налево — сунь мне в клюв окорок. А ежели не станешь этого делать, я тебя сброшу.

Сын белой лошади сделал все так, как ему велела птица-гриф. И они полетели на землю.

Летели они уже долго, вдруг птица-гриф повернула голову направо, тогда Сын белой лошади сунул ей в рот хлеб, потом налево, он сунул ей окорок. Вскоре она съела еще один хлеб, еще один окорок, и, наконец, все было съедено.

Уже пробился свет с земли, когда вдруг птица-гриф повернула голову направо. Сын белой лошади схватил нож и отрезал себе правую руку. Сунул ее в рот птице-грифу. Потом она повернула голову налево, тогда он отдал ей свою правую ногу.

К тому времени, как она съела и это, они долетели доверху и спустились на землю. Но Сын белой лошади не мог сдвинуться с места: он лежал на земле, как скованный, — не было у него ни руки, ни ноги.

Тогда птица-гриф вытащила из-под своего крыла бутылку с вином и отдала ее Сыну белой лошади.

— Ну, — сказала она ему, — за то, что ты оказался таким добрым и отдал мне свои руки и ноги, вот тебе бутылка вина, выпей ее.

Сын белой лошади выпил вино. И что же? Бы бы не поверили, если бы не я это рассказывал, — у него вдруг выросли и рука и нога, да и силушки прибавилось против прежнего в семь раз больше.

Птица-гриф улетела обратно под землю. А Сын белой лошади пустился на розыски своих помощников.

Он шел себе и шел, вдруг ему повстречалась большая отара овец. Он спросил чабана:

чтобы в разгар лета и снег!

И она сама направилась к выходу. Подошла и видит, что это не снег, а белая лошадь лежит.

Задумалась лиса: как бы оттащить ее подальше? Кликнула она сыновей, взялись они вчетвером, а лошадь ни с места.

Тогда старая лиса решила пойти к своему куму волку.

Пришла и говорит:

— Милый мой куманек. И какой же я раздобыла лакомый кусок. До норы уже было дотащила, а он никак не влезает в нее. Вот я и надумала, давай-ка перетащим его в твое логово, может быть в него он и влезет. А есть его будем пополам.

Обрадовался волк славному угощению, а про себя подумал:

«Было бы мясо в моем логове, а там уж лиса ни кусочка не получит».

Они подошли к месту, где лежала белая лошадь.

Волк даже усомнился:

— Скажи, кумушка, а как же дотащить ее до моего логова?

— Да очень просто, — ответила лиса. — Так же, как я тащила ее сюда: привязала за хвост к моему хвосту и волокла ее по рытвинам и ухабам. И до чего же легко мне было! А теперь давай привяжем ее хвост к твоему хвосту, тебе дотащить куда легче.

— Вот это будет здорово, — решил волк и тут же согласился.

А лисица крепко-накрепко привязала волчий хвост к хвосту белой лошади.

— Давай, кум, тащи!

Потянул волк, чуть не лопнул от натуги, а лошадь ни с места. Еще пуще напрягся, и вдруг белая лошадь вскочила на ноги и понеслась. Тащила она волка за хвост через рытвины и ухабы до тех пор, покуда не приволокла его к бедняку.

— Получай, хозяин, — нашла я себе подмогу.

Бедняк тут же прикончил волка, шкуру его продал за большие деньги и купил на них вторую лошадь.

С тех пор белая лошадь уже не вертела больше жернова одна.

СМОРОДИНКА

Быль это или небылица, а за семью морями жила старая вдова. У той вдовы росла красавица дочка. Она очень любила смородину, за это, видно, и прозвали ее Рибике, что значит — Смородинка.

Вот старуха вдова померла и осталась Смородинка сиротою.

Кто о бедняжке позаботится? Пришлось Смородинке задуматься, как же ей быть теперь, каким делом заняться, чтобы не помереть с голоду.

В том же городе, где и Смородинка, жила одинокая старуха. Прослышала она о том, какая хорошая и красивая девушка эта Смородинка, и послала к ней соседку сказать, что с радостью возьмет к себе девушку и станет ее кормить до самой своей смерти. А Смородинка за это будет помогать ей по хозяйству.

Поселилась Смородинка у старухи.

Переделав всю работу за день, Смородинка садилась у окна и вышивала или вязала. Никто ее не трогал, не обижал, как не раз случалось с сиротами.

В том же городе жил богач. У него было три сына. Однажды они проходили мимо дома, где жила Смородинка, и как раз той порой, когда она сидела у окна и вышивала. Самый младший из братьев увидел ее и сразу полюбил, да так крепко, что и жизнь ему стала не в жизнь, еда не в еду, питье не в питье, он все только о Смородинке одной и думал.

И Смородинка полюбила его. А богач, как узнал, что сыну его приглянулась бедная девушка, разгневался и велел слугам увезти несчастную Смородинку на край света и там бросить.

Тщетно бродил младший сын под ее окном. Была Смородинка, и не стало Смородинки, не увидит он ее больше никогда!.. День-деньской грустил он, тосковал, словно голубок на ветке.

Но вот однажды богач позвал к себе всех трех сыновей и сказал им:

— Тот, кто из вас принесет мне полотно в сто аршин шириною и в сто аршин длиною, да притом такое, чтоб продевалось сквозь кольцо золотое, получит третью часть моего добра.

Сыновья собрали свои пожитки и отправились в путь-дорогу. Два старших сына были злые, и они сговорились так:

— Давай убежим от младшего, один он погибнет, и тогда все добро достанется нам!

Так они и сделали — ушли тайком от младшего брата; тот остался один и пошел как раз по той дороге, которая вела на край света.

Брел он, брел печально, прошел уже семь стран и не останавливался до тех пор, пока не попал на самый край света. Там он добрался до каменного мостика и так как очень устал, то сел на перила. Сел и задумался. Что ж ему теперь делать? Вот он уже на краю света, а нет ни полотна и ничего, что можно было бы принести отцу.

Пока он так, задумавшись, сидел на мосту, из травы выскочила маленькая ящерица.

— Что пригорюнился, прекрасный юноша? — спросила она.

Юноша не сразу очнулся от задумчивости. Лишь когда ящерица снова повторила свой вопрос, он взглянул на нее и так ей ответил:

— Что пригорюнился? А тебе что до этого? Оставь меня, милая ящерица!

Ящерица глянула на юношу своими умными глазами.

— Зачем ты гонишь меня? — сказала она. — Не надо меня гнать. Я ведь тебе зла не желаю!

Юноша не стал ее слушать и снова погрузился в размышления. Но ящерица не унималась, все бегала возле него в траве.

— Да скажи ты мне, прекрасный юноша, какая печаль гложет тебя? Может быть, я сумею тебе помочь!

Тут юноша улыбнулся от души. Ну чем может ему помочь такая малютка? Он даже не ответил ей. Но ящерица все твердила свое:

— Откройся мне, прекрасный юноша, расскажи, что за невзгоды печалят тебя? А вдруг я смогу тебе помочь?

Тогда юноша ответил ей:

— Уж если тебе так хочется помочь, то я расскажу тебе все. Отец приказал нам, братьям, принести ему такой кусок полотна, который был бы в сто аршин длиною и в сто аршин шириною и все-таки продевался бы через колечко золотое. Братья мои и я отправились на поиски за этим диковинным полотном. Но кто знает, чем увенчаются все наши старания?

— Ну, если беда только в этом, — сказала маленькая ящерица, — тогда, быть может, я тебе помогу. Побудь здесь, я скоро вернусь.

И она исчезла в траве.

Пошла ящерица к паукам. Рассказала им, что ей надобно.

Пауки ответили:

— Ладно, ящерица, уж тебе ли не услужить. Только подожди немного. Сейчас мы для тебя изготовим полотно.

Тут же сотни пауков задвигались, закружились; прошло немного времени, и полотно было готово. Да еще какое! В сто аршин длиною и в сто аршин шириною и все-таки продевалось сквозь колечко золотое.

— Вот тебе, ящерица, полотно, — сказали пауки. — Готово оно. Бери, коли надо!

Взяла ящерица полотно, уложила в ореховую скорлупу и побежала к юноше.

А он все сидел на мосту и горевал. Вдруг юноша встрепенулся — что-то упало перед ним на землю. Глянул, — а это ящерица орех обронила.

— Что ты принесла, маленькая ящерица? — спросил юноша.

— Я принесла то,

Текст книги «Пера-богатырь (Сказки финно-угорских народов)»

Автор книги: Народные сказки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

НЕДОПАРУШЕК

Саамская сказка

ДЕВУШКА жила на одном конце озера, а парень на другом его конце. Девушку звали Уточкой, а парня Пейвальке – Солнца Сын.

Он был рыболов, часто ездил по озеру, ставил сети тут и там, а удил очень далеко, где «дома рыб» бывают. Однажды он заехал за три далеких острова и вдруг увидел: на угорышке мыса вежа стоит. Привернул он лодку к берегу, поднялся на гору и увидел девушку Уточку.

Он сразу полюбил ее.

Сказал ей:

– Ты одна живешь здесь, а я один живу там – давай жить вместе.

Уточка ответила, что согласна жить вместе, но в лодку к нему она не сядет, пока он не даст ей обещание:

– Когда мы будем ехать по озеру, что бы ты ни увидел – не удивляйся, не смотри, не замечай, даже виду не показывай, что ты что-нибудь видишь!

Парень, конечно, согласился.

Тогда она сказала:

– Вот тебе три яичка. Береги их, храни пуще глаза, держи их у сердца своего. Пусть будут теплые, не застуди!

Пейвальке яички припрятал. Он положил их за пазуху, – холодновато тут, но больше девать их было некуда.

– Согревай яички те, – сказала девушка. – А если случится беда, бросай их в меня. Не бойся, смело в меня бросай!

Сказала так и села в лодку. И вот поехали они в дом Пейвальке. Едут по озеру, смотрят, берегами любуются, острова мимо них проплывают, словно они над водой летят, вокруг рыбы играют и плещутся, круги так и ходят по воде – это рыбы играют, тут «дома рыб» находятся. Хорошо. Однако Пейвальке ни на что не глядит, он Уточкой любуется, на Уточку смотрит, Уточку только и видит.

Вдруг с неба на остров тень упала. Свет брызнул. Засияло все, свет от воды отражается, а откуда псе исходит, неведомо. Пейвальке внимания не обращает, едет себе и едет, веслом весело поигрывает да Уточкой любуется. Остром обогнули, и тут-то воссиял из воды камень. Камень не простой, тот камень был медный камень. И лицо девицы Уточки, и берег дальний, и остров ближний – все осветилось светом этого медного камня.

Тут и закричал Пейвальке Уточке:

– Смотри, смотри, краса какая перед нами открылась – медный камень явился, как огонь горит! Привернем, посмотрим, что за камень такой?

Отвечает ему Уточка:

– Ты мне обещал, что бы ни случилось, мы не видим, не слышим, не смотрим, мимо плывем.

Пейвальке смолчал, дальше поехали. Ехали, ехали, долго ехали, и опять тень мелькнула и за островом спряталась. И опять сияла земля: остров ближе – сильнее свет. Обогнули они и этот остров, а за ним камень лежит серебром так и блистает, лучи летят в небо, небо серебром переливается, и берег и острова серебряными лучами играют, а и лес-то на острове серебряный, небывалый, так и хочется между тех серебряных елей и березок прогуливаться и веточки ломать, серебряные листья собирать.

Опять Пейвальке просит Уточку:

– Смотри, как хорошо, тут бы нам и жить! Давай привернем!

Девица молчит, только смотрит с укором.

– Что тут делается? Что творится? Ехал я себе, ничего такого не видел, а еду с тобой – погляди, дивные камни из земли поднимаются, светятся, нам дорогу освещают.

Девушка ему говорит:

– Что бы ни случилось – мы не видим, не слышим, не смотрим, незачем нам ехать к этим камням!

И на этот раз послушался Пейвальке. И этот камень они миновали, остались позади камень медный и камень серебряный.

Дальше поехали.

Ехали, ехали, опять тень на остров упала. Долго плыли они, уже виден стал дом Пейвальке. Уже миновали его лучший «рыбный дом», как опять увидели: впереди свет лучами вверх летит, в небо стремится. И опять из воды камень растет, словно солнце сверкает этот камень. А камень-то не простой – чисто золотой, и свет от него идет золотистый. Все светится золотом – и берег дальний, и ближний остров, и лесок над ним, и даже вода золотится от этого света. А рыбы-то! Рыбы в озере плавают и тоже золотистые.

– Ну, уж этого камин я не миную! – воскликнул Пейвальке. – Около самого дома моего такое диво дивное живет, камень чистого золота лежит, а я буду мимо ехать и даже глазом не моргну. Не бывать тому!

А сам уж не на Уточку смотрит, а на камень глядит золотой, как на свой.

И он направил лодку к этому камню. Очень не хотелось Уточке приворачивать, но Пейвальке круто свернул лодку в сторону от прямого пути. Встрепенулась Уточка. Встала. Руки подняла, словно собираясь взлететь…

Только причалила лодка к золотому камню, как стало ясно, что не камень это, а сама Выгахке злая, сама подземная хозяйка перед ними. Это она прикинулась сначала медным, потом серебряным, а теперь золотым камнем, это она распустила по ветру свои волосы так, что страшно на небо смотреть… А Пейвальке-то видел их золотыми лучами.

Выгахке выскочила из воды, выхватила из лодки Уточку и в озеро швырнула, на ее же место свою дочку – Выгахкенийду ткнула.

Но Уточка была не проста, она еще и воды не коснулась, как превратилась в птицу летучую – в настоящую птицу. Не растерялся и Пейвальке – метнул он яички, одно за другим, прямо в Уточку. Уточка склюнула одно яйцо и проглотила его. И другое глотнула, а третье-то не смогла, подхватила его на лету, удержала в клюве, а заглотнуть не смогла. Так и полетела с яйцом в клюве, домой.

Остался Пейвальке один. И поехал он домой не с Уточкой милой, а с дочерью страшной Выгахке. Это она, Выгахке злая, заставила его жить вместо Уточки с дочкой своей – Выгахкенийдой.

Ну и стали жить.

Уточка прилетела домой. Превратилась она в простую девушку человечью и зажила по-старому – одна. Два яичка она носила в себе, а третье-то так и не могла проглотить, осталось оно снаружи, она его держала за щекой. Двум яичкам было тепло – они хорошо согрелись в животе-то у матери, а третьему за щекой было холодно. Пришло время, и Уточка поняла: скоро у нее будут детки. И правда, родила она трех сыновей – двое родились обликом человечьим, а третий-то не согрелся, не допарился за щекой у матери, так и остался яичком. Старшего сына она назвала Левушкой, второго Правушкой, а третьему имя положила – Недопарушек.

Уточка очень любила Недопарушка. Она берегла его и все боялась, что упадет и разобьется, пропадет ее болезный сынок. Дети жили дружно, росли хорошо, – крепкие выдались ребятки. И Недопарушек вырос – из маленького пестрого яичка он превратился в простое яйцо, только лицо у него стало в крапинку. Возмужали ребята и начали сами, без матери, ездить на озеро и ловить рыбу – ставили сети тут и там. С каждым годом они заезжали на лодке в глубину озера, забирались в такие места, где никогда еще не бывали. Заезжали даже за три острова, что издали видны были, словно летят они по-над гладью воды. Мимо «рыбного дома» не раз они плавали, где рыбы играют и плещутся. Так-то вот они ездили-ездили, а однажды заехали в далекий залив. Пристали к берегу, хотели рыбу поудить да ухи сварить, а тут-то на другом берегу домик увидели. Дом не простой, а вернее сказать, настоящие хоромы – и сени большие, и горницы по сторонам просторные.

В хоромах жил человек с женою, с той самой дочкой Выгахкиной. Сыновья не догадались, к кому они попали, не поняли, что в этом доме отец их живет. А отец не знал, что его дети к нему в гости пожаловали. Догадалась обо всем одна только Выгахкенийда.

– Ага! Это сынки моего мужа из яиц повылупились! – сказала она и губами причмокнула от удовольствия, она задумала их съесть.

Выгахкенийда зазвала братьев в дом. напоила и накормила их. В горнице с печкой она сама им постелила постели. Спать их уложила и мехами сверху укрыла: «Спите, детки!»

А Недопарушку жарко стало. Он из мехов на волю выбрался. Братья его положили на печку, на шесток у печки, на ветерок, а сами смотрели – не свалился бы он, не разбился бы: они его берегли, они любили братца своего Недопарушку.

Уложили Недопарушка на шесток, а сами крепко уснули. Один Недопарушек не спит: он братьев своих стережет. Заприметил он, что дочка Выгахки недоброе затеяла.

Учуяла Выгахкенийда, что ребята уснули, – она к двери легонечко подкралась и тихонько стукнула, а сама-то спрашивает:

– Спят ли гости? Отдыхают ли гости?

Недопарушек – он не спит, не дремлет, все видит, все слышит – отвечает ей:

– Не спят гости, не отдыхают гости, готовят тебе калену стрелу, тебя убить собираются.

Выгахкенийда от двери ушла, – не спят гости, так и делать тут нечего.

Дна раза так-то вот приходила Выгахкенийда и оба раза спрашивала через двери:

– Спят ли гости, отдыхают ли гости?

Недопарушек так же ей отвечал:

– Не спят гости, не отдыхают гости, готовят калену стрелу, тебя, Выгахке злую, убить хотят.

Утром встали братцы рано, Выгахкенийда их в дорогу снарядила. Уехали они домой к матери и рассказали Уточке, что нашли они дом неведомый какой, а в горнице там меха и таково-то сладко спится. Недопарушек о том промолчал. Мать сразу догадалась, что это за дом такой, где тепло и сладко спится, и какой там старик с женою живет. Она им объяснила, какой это дом и что за хозяйка в том доме поселилась. Уточка сказала, что жена отца – женщина не простая, она дочь подземной хозяйки Выгахке злой, она Выгахкенийда, может их со свету сжить и загубить – не след им ездить в дом отца, к Выгахке злой. Захочет отец – он сам вернется к своим детям.

Настала осень, ночи пришли темные, холодные, дожди начались. А ребята рыбную ловлю не бросали, ездили на озеро, не ленились, рыбачили. Однажды пала непогода сильная, да еще мороз ударил трескучий. Довелось братьям привернуть к дому отца – отдохнуть в нем, обогреться, свежей ухи отведать, ночь скоротать.

И опять Выгахкенийда встретила их как добрая хозяйка, она и печку истопила в горнице, чтобы спать им было сладко.

И повалились братья в постели пуховые, мехом укрытые, а Недопарушка-то на шесток уложили. Пусть его лежит на покое, в ямочке, пусть его ветром проносит. А печка-то сильно истоплена. Жарко на печке. Братья уснули, а Недопарушку-то очень уж тепло, чересчур уж жарко бедняжке. Недопарушек начал угорать. Недопарушек начал слабеть, Недопарушек болезненный стал. А Выгахкенийда уже тут. Тут у двери стоит: стук, стук… и спрашивает:

– Спят ли гости, отдыхают ли гости?

Еле-еле мог ответить ей Недопарушек тоненьким голосом, едва-едва слышным:

– Не спят гости, не отдыхают гости, калену стрелу готовят – тебя, Выгахкину дочку, убить хотят.

Однако Выгахкенийда услышала, что там Недопарушек ответ дает. Ушла она.

Мало-мало обождала – снова явилась и опять спрашивает:

– Спят ли гости, отдыхают ли гости?

Недопарушек услышал, жарко ему, задыхается он, но сипленьким голоском, совсем даже чуть-чуть только слышным, он прошептал:

– Не спят гости, не отдыхают гости, калену стрелу готовят, – тебя, Выгахкину дочку убить хотят!

Однако Выгахкенийда услышала шепот Недопарушка, отошла она от дверей. Обождала немного и опять к двери подкралась – тук, тук:

– Спят ли гости, отдыхают ли гости?

Теперь Недопарушек ничего не услышал. Он уже ничего не мог ответить… распарило его на горячей печке, обессилел он, занемог бедненький… ничего он не услышал, ничего уже не мог сказать, слов лишился. Недопарушек лежит, хочет сказать, хочет крикнуть, а даже вздохнуть он не может.

Тут-то Выгахкенийда в горницу вошла. Недопарушка проглотила, а двух ребят на мороз выбросила, – пусть про запас там лежат. Чуть не замерзли братцы Недопарушкины, однако не вовсе умерли.

Материнское сердце чуяло, что детям беда грозит, что Недопарушек задыхается, что плохо ему, что слова сказать он не может. Встрепенулась она, превратилась в утку и полетела в дом Выгахкенийды, в дом отца ее детей. Знала уже, куда ей лететь! Вошла потихоньку. Увидела постели, мехом покрытые, – подумала:

– Там дети спят! А Недопарушек где?

Стала искать Недопарушка. Нет ее сыночка любимого. Нет нигде яичка серенького в крапинку! Не нашла. Бросилась к детям: не тут ли он, среди братьев спит. А детей-то нет под мехами! Она на улицу выбежала, а сынки ее на крыше лежат – совсем замерзшие. Она их давай тормошить, разогревать своим дыханием. Ничто не помогало. Тут-то поняла она, что не живые они, замороженные. Пала Уточка на тела своих детей и начала плакать и рыдать, голосом причитать:

Убиты Левушка и Правушка!

А где же мой Недопарушка?

Сколько я учила, просила я, говорила —

Придет он, отец, придет, сам он приедет!

Не ездите вы в дом отцовский, неродимый.

В дом отца Выгахке вошла!

Выгахкенийда злая в доме том живет!

Не послушали мать, вы ослушались,

Сами себя загубили,

Загубили себя понапрасну!

Через все озеро услышал голос Уточки муж ее нареченный. Вернулся с охоты, прибежал домой и признал жену свою любимую.

А Уточка его укоряла:

Что же ты, муж мой дорогой,

Выгахкенийде злой послушный,

Послушный мужик, рыбак и охотник!

Что же ты не любил, не берег трех яичек моих,

Детей своих, сироток моих дорогих?!

Двое лежат в снегу неподвижные.

А Недопарушек милый! Где ты?

Недопарушка родного и вовсе-то нету в живых!

Отец нашел Выгахкенийду, она в амбарах спряталась, привел ее и сказал:

– Сумела ты детей моих заморозить, теперь сумей же их оживить, а нет, – не можешь жизнь им вернуть, – я тебя самую сделаю такою, как они здесь лежат.

Выгахкенийда очень испугалась. – она дунула, она плюнула, – и старший, Левушка, ожил, встал, к отцу подошел с левой руки.

Дунула, плюнула Выгахкенийда еще раз, и второй сын, Правушка, ожил, с правой руки отца он встал.

А Недопарушек где? Где Недопарушек? Нет нигде Недопарушка! Проглотила его Выгахкенийда злая.

Братья прогнали дочку Выгахке. Отца они взяли с собою и поехали к себе домой, в дом матери Уточки.

ТО ЛИ БЫЛО, ТО ЛИ НЕ БЫЛО

Саамская сказка

РАССКАЗЫВАЛ один саам у костра то ли быль, то ли небылицу, то ли сказку, то ли байку. Говорил, что все это с ним самим приключилось. И вы послушайте, если время есть, если других дел нету.

Вот с чего все началось: запоздала как-то весна в северных краях. Давно бы ей пора прийти, а что ни день – ветер дует, снег с неба валит. Вот наш саам и думает: непорядок какой-то на небе, надо бы туда забраться, посмотреть, что там такое. А как туда залезть? Земля низко, небо высоко!

Однако наш саам не дурак был, придумал. Взял топор да рубанок, пошел в лес. Свалил большую сосну и начал ее рубанком строгать. До тех пор трудился, пока всю не выстругал. Гора стружек выше леса поднялась. Постелил саам наверх мокрую рогожу, встал на нее и поджег стружки. Вспыхнул огонь, начала рогожа сохнуть, пошел от нее густой пар. Подхватил пар саама, покачал-покачал и вверх понес.

Несло его торчком, несло его кувырком и донесло до облаков. Там саам ухватился за край тучи, да и влез на нее.

Ходит по небу, смотрит. Скучно ему там показалось: пусто, бело кругом, живой души нет, только облака под ногами, как сугробы, лежат…

Поглядел – вдали одно облако выше других вздымается, точь-в-точь круглый снежный дом.

«Значит, живет все-гаки кто-то на небе!»– обрадовался саам и побежал к тому облачному дому.

Вошел в дом, а там Гром сидит. По рукам, по ногам связан.

– Хорошо, что ты пришел, человек, – говорит Гром. – Развяжи меня поскорее!

Саам отвечает:

– Развяжи тебя – ты греметь начнешь! Я боюсь. Пусть тебя тот развязывает, который связал.

– Глупый ты человек. – рассердился Гром. – Да ведь меня Мороз связал. Зачем ему меня развязывать? Пока я не загремел, он на земле хозяин. Весна в тундре не начнется.

«Вот оно что! – подумал саам. – Раз так. надо развязывать».

Распутал узлы на руках – Гром рукавами взмахнул. Загремело кругом, так саама в сторону и отшвырнуло. Хорошо, что туча мягкая: упал – не ушибся.

А Гром его торопит:

– Скорей ноги развязывай!

Как быть? Начал дело – кончать надо. Зажмурился саам от страха и развязал Грому ноги.

Ох, что тут поднялось! Гром ногами топочет – грохот такой, что оглохнуть можно. Руками молнии на землю мечет – блеск такой, что ослепнуть можно.

Совсем перепугался наш саам. Одно только у него в голове: как бы поскорей с этого неба убраться! Прыгнуть бы вниз, да очень уж высоко. Тут как раз мимо него молния стрелой пролетала. Саам схватился за нее. Моргнуть не успел, как пала молния на землю. И саам с ней.

Угодил он прямо в болото. Ушел по самые плечи, только голова над трясиной поднимается. Попробовал саам выбраться, да куда там! Еще глубже увяз.

А кругом весна, морошка белым цветом расцветает, птицы хлопочут…

Прилетела на болото пара лебедей. Смотрит лебедиха – торчит что-то из трясины. Пень не пень, кочка не кочка, а для гнезда годится. Свила лебедиха гнездо на голове у саама. Положила три яйца, села насиживать.

Саам все терпит. Если уж в болоте увяз, так оно, может, и лучше. Солнце печет – гнездо ему макушку прикрывает. Дождь зарядит – он не мокнет.

Как-то отлучилась лебедиха ненадолго. Тут и пожаловал гость. Давно волк гнездо учуял, а теперь по кочкам к нему подобрался. Полакомился лебедиными яйцами, да, видно, мало ему показалось. Стал искать еще, ворошить гнездо лапами. Дерет твердыми когтями голову саама, а тот крикнуть боится, только глазами моргает, кряхтит. Наконец повернулся волк, чтобы назад идти. А саам изловчился и схватил зубами волка за хвост. Крепко стиснул зубы, хоть умри – не выпустит.

Теперь уже волк перепугался. Рванулся вперед, саама из болота выдернул. Еще три прыжка – саама на сухое место выволок.

Тут разжал зубы саам. Волк наутек в лес пустился, а наш саам домой побежал.

Не раз и не два саам у костра рассказывал, что с ним приключилось. Кто верил, кто не верил. Кто говорил: сказка, кто говорил: небылица. А саам все свое твердит: «Быль это, чистая правда! Разве такое выдумаешь?!»

БЕЛАЯ ЛОШАДЬ

Венгерская сказка

ЖИЛ на свете бедный человек. Не было у него ничего, кроме белой лошади. Зарабатывал он на хлеб тем, что гонял свою лошадь на мельницу, впрягал ее там в привод, и она послушно ходила по кругу. День-деньской молола мельница зерно, день-деньской работал бедняк на своей лошади. Очень это надоело бедной лошадке. И она сказала хозяину:

– Хозяин ты мой хороший, почему это другие люди двух лошадей запрягают в привод и только меня ты запрягаешь не в пару? Маюсь я на этой мельнице одна. Целый день хожу по кругу, верчу и верчу тяжелые жернова.

– Лошадушка моя, – ответил ей бедняк, – причина тут простая. Ведь у меня не то что коня или мелкой скотинки, букашки даже – и той нет, чтобы припрячь к тебе.

Тогда белая лошадь сказала своему хозяину:

– Коли беда только в этом, дай ты мне волю, и я сама найду себе подмогу.

Бедняк тут же распряг свою лошадь, и побрела она куда глаза глядят.

Пошла бедная в путь-дорогу. Шла, шла, вдруг видит – лисья нора. Раскинула умом белая лошадь и вот что решила: «Лягу возле самой лисьей норы и прикинусь мертвой».

А в лисьей норе жила старая лисица с тремя лисятами. Одна лисичка, что поменьше, захотела вылезть из норы. Подошла к выходу, увидела белую лошадь и решила, что на дворе снег.